Nobel Peace Prize

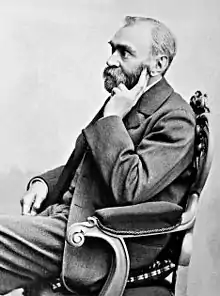

The Nobel Peace Prize is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the will of Swedish industrialist, inventor, and armaments (military weapons and equipment) manufacturer Alfred Nobel, along with the prizes in Chemistry, Physics, Physiology or Medicine, and Literature. Since March 1901,[4] it has been awarded annually (with some exceptions) to those who have "done the most or the best work for fraternity between nations, for the abolition or reduction of standing armies and for the holding and promotion of peace congresses".[5]

| Nobel Peace Prize | |

|---|---|

| Norwegian: Nobels fredspris | |

| |

| Awarded for | Outstanding contributions in peace |

| Location | Oslo, Norway |

| Presented by | Norwegian Nobel Committee on behalf of the estate of Alfred Nobel |

| Reward(s) | 10 million NOK (2020)[1] |

| First awarded | 10 December 1901[2] |

| Currently held by | World Food Programme (2020)[3] |

| Most awards | International Committee of the Red Cross (3) |

| Website | Nobelprize.org |

In accordance with Alfred Nobel's will, the recipient is selected by the Norwegian Nobel Committee, a five-member committee appointed by the Parliament of Norway. The 2020 prize will be awarded in the Atrium of the University of Oslo, where it was also awarded 1947–1989; the Abel Prize is also awarded in the building.[6] The prize was previously awarded in Oslo City Hall (1990–2019), the Norwegian Nobel Institute (1905–1946), and the Parliament (1901–1904).

Due to its political nature, the Nobel Peace Prize has, for most of its history, been the subject of numerous controversies. The most recent prize was awarded to the World Food Programme in 2020; nominations for the 2021 prize closed in January 2021.[7]

Background

According to Nobel's will, the Peace Prize shall be awarded to the person who in the preceding year "shall have done the most or the best work for fraternity between nations, for the abolition or reduction of standing armies and for the holding and promotion of peace congresses".[8] Alfred Nobel's will further specified that the prize be awarded by a committee of five people chosen by the Norwegian Parliament.[9][10]

Nobel died in 1896 and he did not leave an explanation for choosing peace as a prize category. As he was a trained chemical engineer, the categories for chemistry and physics were obvious choices. The reasoning behind the peace prize is less clear. According to the Norwegian Nobel Committee, his friendship with Bertha von Suttner, a peace activist and later recipient of the prize, profoundly influenced his decision to include peace as a category.[11] Some Nobel scholars suggest it was Nobel's way to compensate for developing destructive forces. His inventions included dynamite and ballistite, both of which were used violently during his lifetime. Ballistite was used in war[12] and the Irish Republican Brotherhood, an Irish nationalist organization, carried out dynamite attacks in the 1880s.[13] Nobel was also instrumental in turning Bofors from an iron and steel producer into an armaments company.

It is unclear why Nobel wished the Peace Prize to be administered in Norway, which was ruled in union with Sweden at the time of Nobel's death. The Norwegian Nobel Committee speculates that Nobel may have considered Norway better suited to awarding the prize, as it did not have the same militaristic traditions as Sweden. It also notes that at the end of the 19th century, the Norwegian parliament had become closely involved in the Inter-Parliamentary Union's efforts to resolve conflicts through mediation and arbitration.[11]

Nomination and selection

The Norwegian Parliament appoints the Norwegian Nobel Committee, which selects the Nobel Peace Prize laureate.

Nomination

Each year, the Norwegian Nobel Committee specifically invites qualified people to submit nominations for the Nobel Peace Prize.[14] The statutes of the Nobel Foundation specify categories of individuals who are eligible to make nominations for the Nobel Peace Prize.[15] These nominators are:

- Members of national assemblies and governments and members of the Inter-Parliamentary Union

- Members of the Permanent Court of Arbitration and the International Court of Justice at the Hague

- Members of Institut de Droit International

- Academics at the professor or associate professor level in history, social sciences, philosophy, law, and theology, university rectors, university directors (or their equivalents), and directors of peace research and international affairs institutes

- Previous recipients, including board members of organizations that have received the prize

- Present and past members of the Norwegian Nobel Committee

- Former permanent advisers to the Norwegian Nobel Institute

_-_THE_NOBEL_PEACE_PRIZE_LAUREATES_FOR_1994_IN_OSLO..jpg.webp)

The working language of the Norwegian Nobel Committee is Norwegian; in addition to Norwegian the committee has traditionally received nominations in French, German and English, but today most nominations are submitted in either Norwegian or English. Nominations must usually be submitted to the committee by the beginning of February in the award year. Nominations by committee members can be submitted up to the date of the first Committee meeting after this deadline.[15]

In 2009, a record 205 nominations were received,[16] but the record was broken again in 2010 with 237 nominations; in 2011, the record was broken once again with 241 nominations.[17] The statutes of the Nobel Foundation do not allow information about nominations, considerations, or investigations relating to awarding the prize to be made public for at least 50 years after a prize has been awarded.[18] Over time, many individuals have become known as "Nobel Peace Prize Nominees", but this designation has no official standing, and means only that one of the thousands of eligible nominators suggested the person's name for consideration.[19] Indeed, in 1939, Adolf Hitler received a satirical nomination from a member of the Swedish parliament, mocking the (serious but unsuccessful) nomination of Neville Chamberlain.[20] Nominations from 1901 to 1967 have been released in a database.[21]

Selection

Nominations are considered by the Nobel Committee at a meeting where a shortlist of candidates for further review is created. This shortlist is then considered by permanent advisers to the Nobel institute, which consists of the institute's Director and the Research Director and a small number of Norwegian academics with expertise in subject areas relating to the prize. Advisers usually have some months to complete reports, which are then considered by the committee to select the laureate. The Committee seeks to achieve a unanimous decision, but this is not always possible. The Nobel Committee typically comes to a conclusion in mid-September, but occasionally the final decision has not been made until the last meeting before the official announcement at the beginning of October.[22]

Awarding the prize

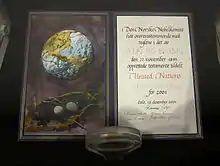

The Chairman of the Norwegian Nobel Committee presents the Nobel Peace Prize in the presence of the King of Norway on 10 December each year (the anniversary of Nobel's death). The Peace Prize is the only Nobel Prize not presented in Stockholm. The Nobel laureate receives a diploma, a medal, and a document confirming the prize amount.[23] As of 2019, the prize was worth 9 million SEK. Since 1990, the Nobel Peace Prize Ceremony is held at Oslo City Hall.

From 1947 to 1989, the Nobel Peace Prize ceremony was held in the Atrium of the University of Oslo Faculty of Law, a few hundred meters from Oslo City Hall. Between 1905 and 1946, the ceremony took place at the Norwegian Nobel Institute. From 1901 to 1904, the ceremony took place in the Storting (Parliament).[24]

Criticism

Some commentators have suggested that the Nobel Peace Prize has been awarded in politically motivated ways for more recent or immediate achievements,[25] or with the intention of encouraging future achievements.[25][26] Some commentators have suggested that to award a peace prize on the basis of the unquantifiable contemporary opinion is unjust or possibly erroneous, especially as many of the judges cannot themselves be said to be impartial observers.[27] The Nobel Peace Prize has become increasingly politicized, in which people are awarded for aspiration rather than accomplishment, which has allowed for the prize to be used for political effect but can cause perverse consequences due to the neglect of existing power politics.[28]

In 2011, a feature story in the Norwegian newspaper Aftenposten contended that major criticisms of the award were that the Norwegian Nobel Committee ought to recruit members from professional and international backgrounds, rather than retired members of parliament; that there is too little openness about the criteria that the committee uses when they choose a recipient of the prize; and that the adherence to Nobel's will should be more strict. In the article, Norwegian historian Øivind Stenersen argues that Norway has been able to use the prize as an instrument for nation-building and furthering Norway's foreign policy and economic interests.[29]

In another 2011 Aftenposten opinion article, the grandson of one of Nobel's two brothers, Michael Nobel, also criticised what he believed to be the politicisation of the award, claiming that the Nobel Committee has not always acted in accordance with Nobel's will.[30]

Criticism of individual conferments

The awards given to Mikhail Gorbachev,[31] Yitzhak Rabin, Shimon Peres, Menachem Begin and Yasser Arafat,[32][33] Lê Đức Thọ, Henry Kissinger,[34] Jimmy Carter,[35] Al Gore,[36] Liu Xiaobo,[37][38][39] Barack Obama,[40][41][42][43] and the European Union[44] have all been the subject of controversy.

The joint award given to Lê Đức Thọ and Henry Kissinger prompted two dissenting Committee members to resign.[45] Thọ refused to accept the prize, on the grounds that such "bourgeois sentimentalities" were not for him[46] and that peace had not been achieved in Vietnam. Kissinger donated his prize money to charity, did not attend the award ceremony and later offered to return his prize medal after the fall of South Vietnam to North Vietnamese forces 18 months later.[46]

In 1994, Kåre Kristiansen resigned from the Norwegian Nobel Committee in protest over the award of the prize to Yasser Arafat, whom he labeled "world's most prominent terrorist".[47]

Notable omissions

Foreign Policy has listed Mahatma Gandhi, Eleanor Roosevelt, U Thant, Václav Havel, Ken Saro-Wiwa, Fazle Hasan Abed and Corazon Aquino as people who "never won the prize, but should have".[48][49]

The omission of Mahatma Gandhi has been particularly widely discussed, including in public statements by various members of the Nobel Committee.[50][51] The committee has confirmed that Gandhi was nominated in 1937, 1938, 1939, 1947, and, finally, a few days before his assassination in January 1948.[52] The omission has been publicly regretted by later members of the Nobel Committee.[50] Geir Lundestad, Secretary of Norwegian Nobel Committee in 2006 said, "The greatest omission in our 106-year history is undoubtedly that Mahatma Gandhi never received the Nobel Peace prize. Gandhi could do without the Nobel Peace prize, whether Nobel committee can do without Gandhi is the question".[53] In 1948, following Gandhi's death, the Nobel Committee declined to award a prize on the ground that "there was no suitable living candidate" that year. Later, when the Dalai Lama was awarded the Peace Prize in 1989, the chairman of the committee said that this was "in part a tribute to the memory of Mahatma Gandhi".[54]

List of Nobel Peace Prize laureates

As of November 2020, the Peace Prize has been awarded to 107 individuals and 28 organizations. 17 women have won the Nobel Peace Prize, more than any other Nobel Prize.[55] Only two recipients have won multiple Prizes: the International Committee of the Red Cross has won three times (1917, 1944, and 1963) and the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees has won twice (1954 and 1981).[56] Lê Đức Thọ is the only person who refused to accept the Nobel Peace Prize.[57]

See also

- Confucius Peace Prize

- Indira Gandhi Peace Prize

- List of Nobel laureates

- List of peace activists

- List of peace prizes

- Nobel Museum

- Nobel Peace Center

- Nobel Peace Prize Concert

- Nobel Prize effect

- Nobel Women's Initiative

- Ramon Magsaysay Award

- World Summit of Nobel Peace Laureates

- List of female nominees for the Nobel Prize

References

- "2020 Nobel Prize Winners: Full List". The New York Times. 12 October 2020.

- "The Nobel Peace Prize 1901". www.nobelprize.org. Retrieved 29 October 2017.

- "The Nobel Peace Prize 2020". 12 October 2020.

- "The Nobel Peace Prize 1901". NobelPrize. 1972. Archived from the original on 2 January 2007. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- "Nobel Peace Prize", The Oxford Dictionary of Twentieth Century World History

- I år skal Nobels fredspris utdeles på UiO

- "Hektisk nomineringsaktivitet før fredsprisfrist". Dagsavisen. 31 January 2021.

- "Excerpt from the Will of Alfred Nobel". Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 31 March 2008.

- Nordlinger, Jay (20 March 2012). Peace, They Say: A History of the Nobel Peace Prize, the Most Famous and Controversial Prize in the World. Encounter Books. p. 24. ISBN 9781594035999.

parliament.

- Levush, Ruth (7 December 2015). "Alfred Nobel's Will: A Legal Document that Might Have Changed the World and a Man's Legacy | In Custodia Legis: Law Librarians of Congress". blogs.loc.gov. Retrieved 12 March 2019.

- "Why Norway?". The Norwegian Nobel Committee. Retrieved 11 October 2009.

- Altman, L. (2006). Alfred Nobel and the prize that almost didn't happen. New York Times. Retrieved 14 October 2006.

- BBC History – 1916 Easter Rising – Profiles – The Irish Republican Brotherhood BBC

- "Nomination for the Nobel Peace Prize". Nobel Foundation. Archived from the original on 30 August 2009. Retrieved 10 September 2009.

- "Who may submit nominations?". The Norwegian Nobel Committee. 8 October 2017. Archived from the original on 30 June 2013. Retrieved 10 September 2009.

- "President Barack Obama wins Nobel Peace Prize". Associated Press on yahoo.com. Retrieved 9 October 2009.

- "Nominations for the 2011 Nobel Peace Prize". Nobel Foundation. Archived from the original on 11 October 2011. Retrieved 7 October 2011.

- "Confidentiality". Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 7 October 2020.

- "Who may submit nominations – Nobels fredspris". Retrieved 10 October 2014.

- Merelli, Annelise. "The darkly ironic 1939 letter nominating Adolf Hitler for the Nobel Peace Prize". Qz.com. Quartz Media. Retrieved 10 November 2017.

- "Nomination Archive – NobelPrize.org". Nobelprize.org. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- "How are Laureates selected?". The Norwegian Nobel Committee. Archived from the original on 31 August 2009. Retrieved 10 September 2009.

- What the Nobel Laureates Receive Archived 30 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine. nobelprize.org.

- "Prisutdelingen | Nobels fredspris". Nobelpeaceprize.org. Archived from the original on 4 November 2012. Retrieved 13 October 2012.

- "Obama Peace Prize win has some Americans asking why?". 9 October 2009 – via Reuters.

- "Obama's peace prize didn't have the desired effect, former Nobel official says". Associated Press. Retrieved 17 September 2015.

- Murphy, Clare (10 August 2004). "The Nobel: Dynamite or damp squib?". BBC online. BBC News. Retrieved 11 October 2009.

- KREBS, RONALD R. (Winter 2009–10). "The False Promise of the Nobel Peace Prize". Political Science Quarterly. 124 (4): 593–625. doi:10.1002/j.1538-165X.2009.tb00660.x. JSTOR 25655740.

- Aspøy, Arild (4 October 2011). "Fredsprisens gråsoner". Aftenposten (in Norwegian). p. 4.

Nobelkomiteen bør ta inn medlemmer med faglig og internasjonal bakgrunn... som gjøre en like god jobb som pensjonerte stortingsrepresentanter.

- Nobel, Michael (9 December 2011). "I strid med Nobels vilje". Aftenposten (in Norwegian). Oslo, Norway. Retrieved 12 December 2011.

- "Gorbachev Gets Nobel Peace Prize For Foreign Police Achievements". The New York Times. 16 October 1990.

- Said, Edward (1996). Peace and Its Discontents: Essays on Palestine in the Middle East Peace Process. Vintage. ISBN 0-679-76725-8.

- Gotlieb, Michael (24 October 1994). "Arafat tarnishes the Nobel trophy". The San Diego Union – Tribune. p. B7.

- "Worldwide criticism of Nobel peace awards". The Times. London. 18 October 1973. Retrieved 11 October 2009.

- Douglas G. Brinkley. The Unfinished Presidency: Jimmy Carter's Journey to the Nobel Peace Prize (1999)

- "A Nobel Disgrace". National Review Online. 22 September 2009. Retrieved 2 October 2011.

- "Overseas Chinese in Norway Protest Against Nobel Committee's Wrong Decision". English.cri.cn. Retrieved 13 October 2012.

- "Not so noble". Frontlineonnet.com. 5 November 2010. Retrieved 13 October 2012.

- "Nobel Harbors Political Motives behind Prize to Liu Xiaobo". English.cri.cn. Retrieved 13 October 2012.

- "Nobel chief regrets Obama peace prize". 17 September 2015 – via www.bbc.com.

- "Surprised, humbled Obama awarded Nobel Peace Prize". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 9 October 2009. Retrieved 9 October 2009.

- Otterman, Sharon (9 October 2009), "World Reaction to a Nobel Surprise", The New York Times, retrieved 9 October 2009

- "Obama Peace Prize win has some Americans asking why?". Reuters.com. 9 October 2009. Retrieved 28 August 2012.

- "Norwegian protesters say EU Nobel Peace Prize win devalues award". Retrieved 8 December 2012.

- Tønnesson, Øyvind (29 June 2000). "Controversies and Criticisms". Nobelprize.org. Retrieved 27 February 2010.

- Horne, Alistair. Kissinger's Year: 1973. p. 195.

- Jay Nordlinger (31 March 2011). "An organized party". National Review. Retrieved 5 November 2020.

- Kenner, David. (7 October 2009). "Nobel Peace Prize Also-Rans" Archived 25 January 2010 at the Wayback Machine. Foreign Policy. Retrieved 10 October 2009

- James, Frank (9 October 2009). "Nobel Peace Prize's Notable Omissions". NPR. Retrieved 12 December 2011.

- Tønnesson, Øyvind (1 December 1999). "Mahatma Gandhi, the Missing Laureate". The Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 17 October 2007.

- Archived 23 March 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- "The Nomination Database for the Nobel Peace Prize, 1901–1956: Gandhi". Nobelprize.org. Retrieved 13 October 2008.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 15 September 2011. Retrieved 15 September 2011.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) Relevance of Gandhian Philosophy in the 21st Century

- "Presentation Speech by Egil Aarvik, Chairman of the Norwegian Nobel Committee". Retrieved 10 October 2014.

- "Facts on the Nobel Peace Prize". Nobel Prize. 2020. Retrieved 7 November 2020.

- "Nobel Laureates Facts". Nobel Foundation. Archived from the original on 1 September 2012. Retrieved 6 October 2011.

- Rothman, Lily. "Why a Nobel Peace Prize Was Once Rejected". TIME.com. Retrieved 16 October 2016.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Nobel Peace Prize. |

- "The Nobel Peace Prize" – Official webpage of the Norwegian Nobel Committee

- "The Nobel Peace Prize" at the official site of the Nobel Prize

- World Summit of Nobel Peace Laureates, official site with information on annual summits beginning in 1999

- "National Peace Nobel Prize shares 1901–2009 by citizenship (or home of the organization) at the time of the award." – From J. Schmidhuber (2010): Evolution of National Nobel Prize Shares in the 20th Century at arXiv:1009.2634v1

- "South Africa is one of the most unequal societies in the world", an article published in Global Education Magazine, by Mr. Frederik Willem de Klerk, Nobel Peace Prize 1993, in the special edition of International Day for the Eradication of Poverty (17 October 2012)

- Martin Luther King, Jr.'s Nobel Peace Prize, Civil Rights Digital Library

- The Nobel Peace Prize Watch, the main project of The Lay Down your Arms Association