History of dance

The history of dance is difficult to access because dance does not often leave behind clearly identifiable physical artefacts that last over millennia, such as stone tools, hunting implements or cave paintings. It is not possible to identify with exact precision when dance became part of human culture.

Early dance

The impulse to dance may have existed in early primates before they evolved into humans.[1] Dance has been an important part of ceremony, rituals, celebrations and entertainment since before the birth of the earliest human civilizations. Archaeology delivers traces of dance from prehistoric times such as the 10,000-year-old Bhimbetka rock shelters paintings in India and Egyptian tomb paintings depicting dancing figures from c. 3300 BC. Many contemporary dance forms can be traced back to historical, traditional, ceremonial and ethnic dances of the ancient period.

Means of social communication and bonding

Dance may have been used as a tool of social interaction that promoted cooperation essential for survival among early humans. Studies found that today's best dancers share two specific genes associated with a predisposition for being good social communicators.[2]

As folk celebrations

Many dances of the early periods were performed to celebrate festivals, on important or seasonal occasions such as crop harvest, or births and weddings. Such dances are found all over the world.[3]

In ceremonies and rituals

Dance may be performed in religious or shamanic rituals, for example in rain dance performed in times of drought. Shamans dancing for rain is mentioned in ancient Chinese texts. Dance is an important aspect of some religious rites in ancient Egypt,[4] similarly dance is also integral to many ceremonies and rites among African people.[5] Ritual dances may also be performed in temples and during religious festivals, for example the Rasa ritual dances of India (a number of Indian classical dances may have their origin in ritual dances), and the Cham dances of Tibet.[6]

As a method of healing

Another early use of dance may have been as a precursor to ecstatic trance states in healing rituals. Dance is used for this purpose by many cultures from the Brazilian rainforest to the Kalahari Desert.[7] Medieval European danses macabres were thought to have protected participants from disease; however; the hysteria and duration of these dances sometimes led to death due to exhaustion.[8]

According to a Sinhalese legend, Kandyan dances originated 2500 years ago, from a magic dance ritual that broke the spell on a bewitched king to cure the king of a mysterious illness.

As a method of expression

One of the earliest structured uses of dances may have been in the performance and in the telling of myths. It was also sometimes used to show feelings for one of the opposite gender. It is also linked to the origin of "lovemaking." Before the production of written languages, dance was one of the methods of passing these stories down from generation to generation.[9]

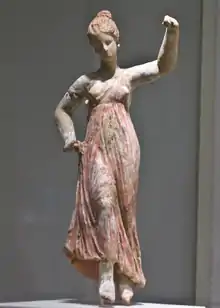

In European culture, one of the earliest records of dancing is by Homer, whose Iliad describes chorea (χορεία khoreia). The early Greeks made the art of dancing into a system, expressive of all the different passions. For example, the dance of the Furies, so represented, would create complete terror among those who witnessed them. The Greek philosopher, Aristotle, ranked dancing with poetry, and said that certain dancers, with rhythm applied to gesture, could express manners, passions, and actions.[10] The most eminent Greek sculptors studied the attitude of the dancers for their art of imitating the passion.

Asia

Indian classical dance

An early manuscript describing dance is the Natya Shastra on which is based the modern interpretation of classical Indian dance (e.g. Bharathanatyam).

During the reign of the last Mughals and Nawabs of Oudh dance fell down to the status of 'nautch', an unethical sensuous thing of courtesans.

Later, linking dance with immoral trafficking and prostitution, British rule prohibited public performance of dance. Many disapproved it. In 1947, India won its freedom and created for dance an ambience where it could regain its past glory. Classical forms and regional distinctions were re-discovered, ethnic specialties were honored, and by synthesizing them with the individual talents of the masters in the line and fresh innovations, emerged dance with a new face but with classicism of the past.

In Sri Lanka, the ancient Sinhalese chronicle Mahavamsa states that when King Vijaya landed in Sri Lanka in 543 BCE he heard sounds of music and dancing from a wedding ceremony. The origins of the dances of Sri Lanka are dated back to the aboriginal tribes, and to the mythological times of aboriginal yingyang twins and "yakkas" (devils). The classical dances of Sri Lanka (Kandyan dances) feature a highly developed system of tala (rhythm), provided by cymbals called thalampataa.

Chinese dance

There is a long recorded history of Chinese dances. Some of the dances mentioned in ancient texts, such as dancing with sleeve movements are still performed today. Some of the early dances were associated with shamanic rituals. Folk dances of the early period were also developed into court dances. The important dances of the ancient period were the ceremonial yayue dated to the Zhou dynasty of the first millennium BC. The art of dance in China reached its peak during the Tang dynasty, a period when dancers from many parts of the world also performed at the imperial court. However, Chinese opera became popular during the Song and Yuan dynasty, and many dances were merged into Chinese opera.[11] The art of dance in women also declined from the Song dynasty onward as a result of the increasing popularity of footbinding,[12] a practice that ironically may have originated from dancing when a dancer wrapped her feet so she may dance ballet-fashion.[13][14] The best-known of the Chinese traditional dances are the dragon dance and lion dance. Lion dance was described in the Tang dynasty in form that resembles today's dance.[11]

Europe

15th–19th centuries: from court dancing to Romanticism

The origins of ballet dancing can be traced to the Italian Renaissance courts of the 15th century. Dance masters would teach the steps to nobility and the court would participate in performances as a form of social entertainment. This practice continued for several centuries. In the 17th century, courtly ballet reached its peak under the rule of King Louis XIV.[15]

By the 18th century, ballet had migrated from the French and Italian royal courts to the Paris Opéra under the careful direction of composer/dancer Jean-Baptiste Lully. Lully sought to develop ballet into more serious art. Under his influence, ballet was turned into a recognized art that was performed by professional dancers rather than courtiers.

During the 18th century, ballet transitioned from a courtly dance of moving images as a spectacle to performance art in its own right. Ballet performances developed around a central narrative and contained an expressive movement that revealed the relationships between characters. This dramatic style of ballet became known as the ballet d'action. The ballet d'action strove to express, for the first time, human emotions drawn directly from the dancers themselves. Masks previously worn by performers were removed so that emotional content could be derived from facial expressions.[15]

Costumes during this time were very restricting for dancers. Although a more expressive use of the body was encouraged, dancers' movements were still restricted due to heavy materials and corseted dresses. Costumes often covered a dancer's physique and made it difficult to see complex or intricate choreography. It was not until choreographer Jean Georges Noverre called for dance reforms in 1760 with his Letters on Dancing and Ballets that costumes became more conducive. Noverre urged that costumes be crafted using lightweight fabrics that move fluidly with the body, complementing a dancer's figure. In addition, dancers wore soft slippers that fit snugly along the foot. This shoe design instilled confidence within the ballerina, daring her to dance on her toes. Naturalistic costuming allowed dancers to push the boundaries of movement, eventually rising en pointe.

The era of Romanticism produced ballets inspired by fantasy, mystique, and the unfamiliar cultures of exotic places. Ballets that focused more on the emotions, the fantasy and the spiritual worlds, heralded the beginning of true pointe-work. Now, on her toes, the deified ballerina (embodied in this period by the legendary ballerina Marie Taglioni) seemed to magically skim the surface of the stage, an ethereal being never quite touching the ground. It was during this period that the ascending star of the ballerina quite eclipsed the presence of the poor male dancer, who was in many cases reduced to the status of a moving statue, present only in order to lift the ballerina. This sad state was really only redressed by the rise of the male ballet star Vaslav Nijinsky, with the Ballets Russes, in the early 20th century. Ballet as we know it had well and truly evolved by this time, with all the familiar conventions of costume, choreographic form, plot, pomp, and circumstance firmly fixed in place.

Early 20th century: from ballet to contemporary dance

Since the Ballets Russes began revolutionizing ballet in the early 20th century, there have been continued attempts to break the mold of classical ballet. Currently the artistic scope of ballet technique (and its accompanying music, jumper, and multimedia) is more all-encompassing than ever. The boundaries that classify a work of classical ballet are constantly being stretched, muddied and blurred until perhaps all that remains today are traces of technique idioms such as turnout.

It was during the explosion of new thinking and exploration in the early 20th century that dance artists began to appreciate the qualities of the individual, the necessities of ritual and religion, the primitive, the expressive and the emotional. In this atmosphere modern dance began an explosion of growth. There was suddenly a new freedom in what was considered acceptable, what was considered art, and what people wanted to create. Many other things were suddenly valued as much as, or beyond, the costumes and tricks of the ballet.

Most of the early-20th-century modern choreographers and dancers saw ballet in the most negative light. Isadora Duncan thought it was ugly, nothing more than meaningless gymnastics. Martha Graham saw it as European and Imperialistic, having nothing to do with the modern American people. Merce Cunningham, while using some of the foundations of the ballet technique in his teaching, approached choreography and performance from a totally radical standpoint compared to the traditional balletic format.

The 20th century was indeed a period of breaking away from everything that ballet stood for. It was a time of unprecedented creative growth, for dancers and choreographers. It was also a time of shock, surprise and broadening of minds for the public, in terms of their definitions of what dance was.

The late 20th and early 21st centuries

After the explosion of modern dance in the early 20th century, the 1960s saw the growth of postmodernism. Postmodernism veered towards simplicity, the beauty of small things, the beauty of untrained body, and unsophisticated movement. The famous "No" manifesto rejecting all costumes, stories and outer trappings in favour of raw and unpolished movement was perhaps the extreme of this wave of thinking. Unfortunately, lack of costumes, stories and outer trappings do not make a good dance show, and it was not long before sets, décor and shock value re-entered the vocabulary of modern choreographers.

By the 1980s dance had come full circle and modern dance (or, by this time, "contemporary dance") was clearly still a highly technical and political vehicle for many practitioners. Existing alongside classical ballet, the two art-forms were by now living peacefully next door to one another with little of the rivalry and antipathy of previous eras. In a cleverly designed comment on this ongoing rivalry, the brilliant collaboration of Twyla Tharp (one of the 20th century's cutting edge Dance avant-gardist/contemporary) and Ballet dance was ultimately achieved. The present time sees us still in the very competitive artistic atmosphere where choreographers compete to produce the most shocking work, however, there are still glimpses of beauty to be had, and much incredible dancing in an age where dance technique has progressed further in expertise, strength and flexibility than ever before in history.

At the same time, mass culture experienced expansion of street dance. In 1973, famous group Jackson 5 performed on television a dance called Robot (choreographed by postmodern[16] artist Michael Jackson), a dance form cultivated in Richmond, CA. This event and later Soul Train performances by black dancers (such as Don Cambell) ignited a street culture revolution, in a sense. B-boying in New York, Locking in L.A., Popping in Fresno, CA, Boogaloo in Oakland, CA, Robot in Richmond, CA, all had their own creative explosions happen around the late 60's - 70's. Each with their own histories, practices, innovators and foundations.

For the emergence of 20th-century modern dance see also: Mary Wigman, Gret Palucca, Harald Kreutzberg, Yvonne Georgi, and Isadora Duncan.

Hip-hop dance started when Clive Campbell, aka Kool DJ Herc and the father of hip-hop, came to New York from Jamaica in 1967. Toting the seeds of reggae from his homeland, he is credited with being the first DJ to use two turntables and identical copies of the same record to create his jams. But it was his extension of the breaks in these songs—the musical section where the percussive beats were most aggressive—that allowed him to create and name a culture of break boys and break girls who laid it down when the breaks came up. Briefly termed b-boys and b-girls, these dancers founded breakdancing, which is now a cornerstone of hip-hop dance.

See also

References

- Frederick, Eva (December 23, 2019). "Dancing chimpanzees may reveal how humans started to boogie". Science. doi:10.1126/science.aba6904.

- Heather Whipps (March 10, 2006). "Survival Dance: How Humans Waltzed Through the Ice Age". Live Science.

- Manorma Sharma (2007). Musical Heritage of India. p. 65. ISBN 978-8131300466.

- "Music & Dance". Pan Historia.

- Kassing, Gayle (15 August 2014). Discovering Dance. Human Kinetics Publishers. p. 132. ISBN 978-1450468862.

- Manohar Laxman Varadpande (1987). History of Indian Theatre, Volume 2. pp. 36–40. ISBN 9788170172789.

- Guenther, Mathias Georg. 'The San Trance Dance: Ritual and Revitalization Among the Farm Bushmen of the Ghanzi District, Republic of Botswana.' Journal, South West Africa Scientific Society, v30, 1975-76.

- Laurson, Jens (Summer 2012). "The Dances, Joys, Pleasures". Listen. p. 45.

- Nathalie Comte. "Europe, 1450 to 1789: Encyclopedia of the Early Modern World". Ed. Jonathan Dewald. Vol. 2. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 2004. p94-108.

- David, A. P. (2006-09-28). The Dance of the Muses: Choral Theory and Ancient Greek Poetics. OUP Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-929240-0.

- Wang Kefen (1985). The History of Chinese Dance. China Books & Periodicals. ISBN 978-0835111867.

- Robert Hans van Gulik (1961). Sexual life in ancient China:A Preliminary Survey of Chinese Sex and Society from Ca. 1500 B.C. Till 1644 A.D. Brill. p. 222. ISBN 9004039171.

- "Chinese Foot Binding". BBC.

- Marie-Josèphe Bossan (2004). The Art of the Shoe. Parkstone Press Ltd. p. 164. ISBN 978-1859958032.

- "A Brief History of Ballet - Illustrated by Pittsburgh Ballet Theatre". Pittsburgh Ballet Theatre. Retrieved 2018-03-29.

- Ntongela Masilela's essay.

Further reading

- Adshead-Lansdale, J. (ed.) (1994). Dance History: An Introduction. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-09030-X.

- Charman, S. Kraus, R, G. Chapman, S. and Dixon-Stowall, B. (1990). History of the Dance in Art and Education. Pearson Education. ISBN 0-13-389362-6.

- Dils, A. (2001). Moving History/Dancing Cultures: A Dance History Reader. Wesleyan University Press. ISBN 0-8195-6413-3.

- Wallace, Carol McD.; et al. (1986). Dance: a very social history. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 9780870994869.

- Wood, Melusine (1952). Some historical dances twelfth to nineteenth century; their manner of performance and their place in the social life of the time, London: Imperial Society of Teachers of Dancing.