History of the Oregon Trail

The Oregon Trail is a historic 2,000-mile (3,264-km) trail used by American pioneers living in the Great Plains in the 19th century. The emigrants traveled by wagon in search of fertile land in Oregon's Willamette Valley.

Lewis and Clark Expedition

In 1803, President Thomas Jefferson issued the following instructions to Meriwether Lewis: "The object of your mission is to explore the Missouri river, & such principal stream of it, as, by its course & communication with the waters of the Pacific Ocean, whether the Columbia, Oregon, Colorado and/or other river may offer the most direct & practicable water communication across this continent, for the purposes of commerce."[1] Although Lewis and William Clark found a path to the Pacific Ocean, it was not until 1859 that a direct and practicable route, the Mullan Road, connected the Missouri River to the Columbia River.

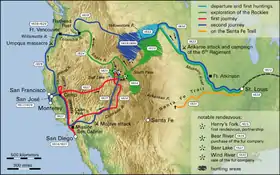

The first land route across what is now the United States was partially mapped by the Lewis and Clark Expedition between 1804 and 1806. Lewis and Clark initially believed they had found a practical overland route to the west coast; however, the two passes they found going through the Rocky Mountains, Lemhi Pass and Lolo Pass, turned out to be much too difficult for wagons to pass through without considerable road work. On the return trip in 1806 they traveled from the Columbia River to the Snake River and the Clearwater River over Lolo pass again. They then traveled overland up the Blackfoot River and crossed the Continental Divide at Lewis and Clark Pass[2] and on to the head of the Missouri River. This was ultimately a shorter and faster route than the one they followed west. This route had the disadvantages of being much too rough for wagons and controlled by the Blackfoot Indians. Even though Lewis and Clark had only traveled a narrow portion of the upper Missouri River drainage and part of the Columbia River drainage, these were considered the two major rivers draining most of the Rocky Mountains, and the expedition confirmed that there was no "easy" route through the northern Rocky Mountains as Jefferson had hoped. Nonetheless, this famous expedition had mapped both the eastern and western river valleys (Platte and Snake Rivers) that bookend the route of the Oregon Trail (and other emigrant trails) across the continental divide—they just had not located the South Pass or some of the interconnecting valleys later used in the high country. They did show the way for the mountain men, who within a decade would find a better way across, even if it was not to be an easy way.

Pacific Fur Company

John Jacob Astor, fur trader, entrepreneur, and one of the wealthiest men in the U.S. created a subsidiary of the American Fur Company, called the Pacific Fur Company in 1810. He funded and outfitted a naval and overland expedition, with the land party led by Wilson Price Hunt to find a possible overland supply route and trapping territory for fur trading posts. Fearing attack by the Blackfoot Indians, the overland expedition veered south of Lewis and Clark's route into what is now Wyoming and in the process passed across Union Pass and into Jackson Hole, Wyoming. From there they went over the Teton Range via Teton Pass and then down to the Snake River in Idaho. They abandoned their horses at the Snake River, made dugout canoes, and attempted to use the river for transport. After a few days' travel they soon discovered that steep canyons, waterfalls and impassable rapids made travel by river impossible. Too far from their horses to retrieve them, they had to cache most of their goods and walk the rest of the way to the Columbia River where they made new boats and traveled to the newly established Fort Astoria. The expedition demonstrated that much of the route along the Snake River plain and across to the Columbia was passable by pack train or with minimal improvements, even wagons.[3] This knowledge would be incorporated into the concatenated trail segments as the Oregon Trail took its early shape.

In early 1811, the supply ship Tonquin left supplies and men to establish Fort Astoria (Oregon) at the mouth of the Columbia River and Fort Okanogan (Washington) at the confluence of the Okanogan and Columbia Rivers. The Tonquin then went up the coast to Puget Sound for a trading expedition. There it was attacked and overwhelmed by Indians before being blown up, killing all the crew and many Indians. Pacific Fur Company partner Robert Stuart led a small group of men back east to report to Astor. The group planned to retrace the path followed by the overland expedition back up to the east following the Columbia and Snake rivers.

Fear of Indian attack near Union Pass in Wyoming forced the group further south where they luckily discovered South Pass, a wide and easy pass over the Continental Divide. The party continued east via the Sweetwater River, North Platte River (where they spent the winter of 1812–1813) and Platte River to the Missouri River, finally arriving in St. Louis in the spring of 1813. The route they had used appeared to potentially be a practical wagon route, requiring minimal improvements, and Stuart's journals provided a meticulous account of most of the route.[4] Because of the War of 1812 and the lack of U.S. fur trading posts in the Oregon Country, most of the route was unused for more than 10 years.

The North West Company and Hudson's Bay Company

In August 1811, three months after Fort Astor was established, David Thompson and his team of British North West Company explorers came floating down the Columbia to Fort Astoria. He had just completed an epic journey through much of British Columbia and most of the Columbia River drainage system. He was mapping the country for possible fur trading posts. Along the way he camped at the confluence of the Columbia and Snake rivers and posted a notice claiming the land for Britain and stating the intention of the North West Company to build a fort on the site (Fort Nez Perces was later established there). Astor, pressured by potential confiscation by the British navy of their forts and supplies in the War of 1812, sold to the North West Company in 1812 their forts, supplies and furs on the Columbia and Snake River. The North West Company started establishing more forts and trading posts of their own.

By 1821, when armed hostilities broke out with their Hudson's Bay Company rivals, the North West Company was pressured by the British government to merge with the Hudson's Bay Company. The Hudson's Bay Company had nearly a complete monopoly on trading (and most governing issues) in the Columbia District, or Oregon Country as it was referred to by the Americans, and also in Rupert's Land (western Canada). That year the British parliament passed a statute applying the laws of Upper Canada to the district and giving the Hudson's Bay Company power to enforce those laws.

From 1812 to 1840 the British through the Hudson's Bay Company had nearly complete control of the Pacific Northwest and the western half of the Oregon Trail. In theory, the Treaty of Ghent ending the War of 1812 restored the U.S. back to its possessions in Oregon territory. "Joint occupation" of the region was formally established by the Anglo-American Convention of 1818. The British through the Hudson's Bay Company tried to discourage any U.S. trappers, traders and settlers from doing any significant trapping, trading or settling in the Pacific Northwest. American fur trappers, traders, missionaries, and later settlers all worked to break this monopoly. They were eventually successful.

The York Factory Express, establishing another route to the Oregon territory, evolved from an earlier express brigade used by the North West Company between Fort Astoria and Fort William, Ontario on Lake Superior. By 1825 the Hudson's Bay Company started using two brigades, each setting out from opposite ends of the express route—one from Fort Vancouver on the Columbia River and the other from York Factory on Hudson Bay—in spring and passing each other in the middle of the continent. This established a 'quick' (about 100 days for 2,600 miles (4,200 km)) one way to resupply their forts and fur trading centers as well as collecting the furs the posts had bought and transmitting messages between Fort Vancouver and York Factory on Hudson Bay.

The Hudson's Bay Company built a new much larger Fort Vancouver in 1824 slightly upstream of Fort Astoria on the Washington side of the Columbia River (they were hoping the Columbia would be the future Canada – U.S. border). The fort quickly became the center of activity in the Pacific Northwest. Every year ships would come from London to the Pacific (via Cape Horn) to drop off supplies and trade goods in their trading posts in the Pacific Northwest and pick up the accumulated furs used to pay for these supplies. It was the nexus for the fur trade on the Pacific Coast; its influence reached from the Rocky Mountains to the Hawaiian Islands, and from Russian Alaska into Mexican-controlled California. At its pinnacle in about 1840, Fort Vancouver and its Factor (manager) watched over 34 outposts, 24 ports, 6 ships, and about 600 employees.

When emigration over the Oregon Trail began in earnest in about 1836, for many settlers the fort became the last stop on the Oregon Trail where they could get supplies, aid and help before starting their homestead. Fort Vancouver was the main re-supply point for nearly all Oregon trail travelers until U.S. towns could be established. Fort Colville[5] was established in 1825 on the Columbia River near Kettle Falls as a good site to collect furs and control the upper Columbia River fur trade. Fort Nisqually was built near the present town of DuPont, Washington and was the first Hudson's Bay Company fort on Puget Sound. Fort Victoria was erected in 1843 and became the headquarters of operations in British Columbia, eventually growing into modern-day Victoria, the capital city of British Columbia.

By 1840 the Hudson's Bay Company had three forts: Fort Hall (purchased from Nathaniel Jarvis Wyeth in 1837), Fort Boise and Fort Nez Perce on the western end of the Oregon Trail route as well as Fort Vancouver near its terminus in the Willamette Valley. With minor exceptions they all gave substantial and often desperately needed aid to the early Oregon Trail pioneers.

When the fur trade slowed in 1840 because of fashion changes in men's hats, the value of the Pacific Northwest to the British was seriously diminished. Canada had very few potential settlers who were willing to move over 2,500 miles to the Pacific Northwest, although several hundred ex-trappers, British and American, and their families did start settling in Oregon, Washington and California. They used most of the York Express route through northern Canada. In 1841 James Sinclair, on orders from Sir George Simpson, guided nearly 200 settlers from the Red River Colony (located at the junction of the Assiniboine River and Red River near the present-day Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada)[6] into the Oregon territory.[7] This attempt at settlement failed when most of the families joined the settlers in the Willamette Valley, with their promise of free land and HBC-free government.

stretched from 42'N to 54 40'N. The most heavily disputed portion is highlighted.

In 1846 the Oregon Treaty ending the Oregon boundary dispute was signed with Britain. The British lost the land north of the Columbia River they had so long controlled. The new Canada–United States border was established much further north at the 49th parallel. The treaty granted the Hudson's Bay Company navigation rights on the Columbia River for supplying their fur posts, clear titles to their trading post properties allowing them to be sold later if they wanted, and left the British with good anchorages at Vancouver and Victoria, British Columbia. It gave the United States what it mostly wanted, a 'reasonable' boundary and a good anchorage on the West Coast in Puget Sound. While there were almost no United States settlers in the future state of Washington in 1846, the United States had already demonstrated it could induce thousands of settlers to go to the Oregon Territory, and it would be only a short time before they would vastly outnumber the few hundred Hudson's Bay Company employees and retirees living in Washington.

By overland travel, American missionaries and early settlers (initially mostly ex-trappers) started showing up in Oregon around 1824. Although officially the Hudson's Bay Company discouraged settlement because it interfered with their lucrative fur trade, their Chief Factor at Fort Vancouver, Dr. John McLoughlin, gave substantial help including employment until they could get established. By 1843, when 700–1,000 settlers arrived, the American settlers greatly outnumbered the nominally British settlers in Oregon. McLoughlin, despite working for the British-based Hudson's Bay Company, gave help in the form of loans, medical care, shelter, clothing, food, supplies and seed to United States emigrants. These new emigrants often arrived in Oregon tired, worn out, nearly penniless, with insufficient food or supplies just as winter was coming on. McLoughlin would later be hailed as the Father of Oregon.

Great American Desert

Reports from expeditions in 1806 by Lieutenant Zebulon Pike and in 1819 by Major Stephen Long described the Great Plains as "unfit for human habitation" and as "The Great American Desert". These descriptions were mainly based on the relative lack of timber and surface water. The images of sandy wastelands conjured up by terms like "desert" were tempered by the many reports of vast herds of millions of Plains Bison that somehow managed to live in this "desert".[8] In the 1840s, the Great Plains appeared to be unattractive for settlement and were illegal for homesteading until well after 1846—initially it was set aside by the U.S. government for Indian settlements. The next available land for general settlement, Oregon, appeared to be free for the taking and had fertile lands, disease free climate (yellow fever and malaria were prevalent in much of the Missouri and Mississippi River drainage then), extensive uncut, unclaimed forests, big rivers, potential seaports, and only a few nominally British settlers.

Fur traders, trappers and explorers

Fur trappers, often working for fur traders, followed nearly all possible streams looking for beaver in the years (1812–1840) the fur trade was active.[9] Fur traders included Manuel Lisa, Robert Stuart, William Henry Ashley, Jedediah Smith, William Sublette, Andrew Henry, Thomas Fitzpatrick, Kit Carson, Jim Bridger, Peter Skene Ogden, David Thompson, James Douglas, Donald Mackenzie, Alexander Ross, James Sinclair and other mountain men. Besides discovering and naming many of the rivers and mountains in the Intermountain West and Pacific Northwest they often kept diaries of their travels and were available as guides and consultants when the trail started to become open for general travel. The fur trade business wound down to a very low level just as the Oregon trail traffic seriously began around 1840.

In fall of 1823, Jedediah Smith and Thomas Fitzpatrick led their trapping crew south from the Yellowstone River to the Sweetwater River. They were looking for a safe location to spend the winter. Smith reasoned since the Sweetwater flowed east it must eventually run into the Missouri River. Trying to transport their extensive fur collection down the Sweetwater and North Platte River, they found after a near disastrous canoe crash that the rivers were too swift and rough for water passage. On July 4, 1824, they cached their furs under a dome of rock they named Independence Rock and started their long trek on foot to the Missouri River. Upon arriving back in a settled area they bought pack horses (on credit) and retrieved their furs. They had re-discovered the route that Robert Stuart had taken in 1813—eleven years before. Thomas Fitzpatrick was often hired as a guide when the fur trade dwindled in 1840. Jedediah Smith was killed by Indians about 1831.

Up to 3,000 Mountain men were trappers and explorers, employed by various British and United States fur companies or working as free trappers, who roamed the North American Rocky Mountains from about 1810 to the early 1840s. They usually traveled in small groups for mutual support and protection. trapping took place in the fall when the fur became prime. Mountain men primarily trapped beaver and sold the skins. A good beaver skin could bring up to $4.00 at a time when a man's wage was often $1.00/day. Some were more interested in exploring the West. In 1825, the first significant American Rendezvous occurred on the Henry's Fork of the Green River. The trading supplies were brought in by a large party using pack trains originating on the Missouri River. These pack trains were then used to haul out the fur bales. They normally used the north side of the Platte River—the same route used 20 years later by the Mormon Trail. For the next 15 years the American rendezvous was an annual event moving to different locations, usually somewhere on the Green River in the future state of Wyoming. Each rendezvous, occurring during the slack summer period, allowed the fur traders to trade for and collect the furs from the trappers and their Indian allies without having the expense of building or maintaining a fort or wintering over in the cold Rockies. In only a few weeks at a rendezvous a year's worth of trading and celebrating would take place as the traders took their furs and remaining supplies back east for the winter and the trappers faced another fall and winter with new supplies. Jim Beckwourth describes: "Mirth, songs, dancing, shouting, trading, running, jumping, singing, racing, target-shooting, yarns, frolic, with all sorts of extravagances that white men or Indians could invent."[10] In 1830, William Sublette brought the first wagons carrying his trading goods up the Platte, North Platte, and Sweetwater River (Wyoming) before crossing over South Pass to a fur trade rendezvous on the Green River near the future town of Big Piney, Wyoming. He had a crew that dug out the gullies and river crossings and cleared the brush where needed. This established that the eastern part of most of the Oregon Trail was passable by wagons. In the late 1830s the Hudson's Bay Company instituted a policy intended to destroy or weaken the American fur trade companies. The Hudson's Bay Company's annual collection and re-supply Snake River Expedition was transformed to a trading enterprise. Beginning in 1834, it visited the American Rendezvous to undersell the American traders—losing money but undercutting the American fur traders. By 1840 the fashion in Europe and Britain shifted away from the formerly very popular beaver felt hats and prices for furs rapidly declined and the trapping almost ceased.

Fur traders tried to use the Platte River, the main route of the eastern Oregon Trail, for transport but soon gave up in frustration as its many channels and islands combined with its muddy waters were too shallow, crooked and unpredictable to use for water transport. The Platte proved to be unnavigable. The Platte River and North Platte River Valley, however, became an easy roadway for wagons, with its nearly flat plain sloping easily up and heading almost due west.

There were several U.S. government sponsored explorers who explored part of the Oregon Trail and wrote extensively about their explorations. Captain Benjamin Bonneville on his expedition of 1832 to 1834 explored much of the Oregon trail and brought wagons up the Platte, North Platte, Sweetwater route across South Pass to the Green River in Wyoming. He explored most of Idaho and the Oregon Trail to the Columbia. The account of his explorations in the west was published by Washington Irving in 1838.[11] John C. Frémont of the U. S. Army's Corps of Topographical Engineers and his guide Kit Carson led three expeditions from 1842 to 1846 over parts of California and Oregon. His explorations were written up by him and his wife Jessie Benton Frémont and were widely published. The first "decent" map[12] of California and Oregon were drawn by Frémont and his topographers and cartographers in about 1848.

Missionaries

In 1834, The Dalles Methodist Mission was founded by Reverend Jason Lee just east of Mount Hood on the Columbia River. In 1836, Henry H. Spalding and Marcus Whitman traveled west to establish the Whitman Mission near modern-day Walla Walla, Washington.[13] The party included the wives of the two men, Narcissa Whitman and Eliza Hart Spalding, who became the first European-American women to cross the Rocky Mountains. En route, the party accompanied American fur traders going to the 1836 rendezvous on the Green River in Wyoming and then joined Hudson's Bay Company fur traders traveling west to Fort Nez Perce (also called Fort Walla Walla). The group was the first to travel in wagons all the way to Fort Hall, Idaho, where the wagons were abandoned at the urging of their guides. They used pack animals for the rest of the trip to Fort Walla Walla and then floated by boat to Fort Vancouver to get supplies before returning to start their missions. Other missionaries, mostly husband and wife teams using wagon and pack trains, established missions in the Willamette Valley, as well as various locations in the future states of Washington, Oregon, and Idaho.

Oregon Country

In 1843, settlers of the Willamette Valley drafted the Organic Laws of Oregon organizing land claims within the Oregon Country. Married couples were granted at no cost (except for the requirement to work and improve the land) up to 640 acres (2.6 km2), and unmarried settlers could claim 320 acres (1.3 km2). As the group was a provisional government with no authority, these claims were not valid under United States or British law, but they were eventually honored by the United States in the Donation Land Act of 1850. The Donation Land Act provided for married settlers to be granted 320 acres (1.3 km2) and unmarried settlers 160 acres (0.65 km2). Following the expiration of the act in 1854 the land was no longer free but cost $1.25 per acre ($3.09/hectare) with a limit of 320 acres (1.3 km2)—the same as most other unimproved government land.

Early emigrants

On May 1, 1839, a group of eighteen men from Peoria, Illinois, set out with the intention of colonizing the Oregon country on behalf of the United States of America and drive out the Hudson's Bay Company operating there. The men of the Peoria Party were among the first pioneers to traverse most of the Oregon Trail. The men were initially led by Thomas J. Farnham and called themselves the Oregon Dragoons. They carried a large flag emblazoned with their motto "Oregon Or The Grave". Although the group split up near Bent's Fort on the South Platte and Farnham was deposed as leader, nine of their members eventually did reach Oregon.[14]

In September 1840, Robert Newell, Joseph L. Meek, and their families reached Fort Walla Walla with three wagons that they had driven from Fort Hall. Their wagons were the first to reach the Columbia River over land, and they opened the final leg of Oregon Trail to wagon traffic.[15]

In 1841 the Bartleson-Bidwell Party was the first emigrant group credited with using the Oregon Trail to emigrate west. The group set out for California, but about half the party left the original group at Soda Springs, Idaho, and proceeded to the Willamette Valley in Oregon, leaving their wagons at Fort Hall.

On May 16, 1842, the second organized wagon train set out from Elm Grove, Missouri, with more than 100 pioneers.[16] The party was led by Elijah White. The group broke up after passing Fort Hall with most of the single men hurrying ahead and the families following later.

Great Migration of 1843

In what was dubbed "The Great Migration of 1843" or the "Wagon Train of 1843",[17][18] an estimated 700 to 1,000 emigrants left for Oregon. They were led initially by John Gantt, a former U.S. Army Captain and fur trader who was contracted to guide the train to Fort Hall for $1 per person. The winter before, Marcus Whitman had made a brutal mid-winter trip from Oregon to St. Louis to appeal a decision by his Mission backers to abandon several of the Oregon missions. He joined the wagon train at the Platte River for the return trip. When the pioneers were told at Fort Hall by agents from the Hudson's Bay Company that they should abandon their wagons there and use pack animals the rest of the way, Whitman disagreed and volunteered to lead the wagons to Oregon. He believed the wagon trains were large enough that they could build whatever road improvements they needed to make the trip with their wagons. The biggest obstacle they faced was in the Blue Mountains of Oregon where they had to cut and clear a trail through heavy timber. The wagons were stopped at The Dalles, Oregon by the lack of a road around Mount Hood. The wagons had to be disassembled and floated down the treacherous Columbia River and the animals herded over the rough Lolo trail to get by Mt. Hood. Nearly all of the settlers in the 1843 wagon trains arrived in the Willamette Valley by early October. A passable wagon trail now existed from the Missouri River to The Dalles. In 1846, the Barlow Road was completed around Mount Hood, providing a rough but completely passable wagon trail from the Missouri River to the Willamette Valley—about 2,000 miles.

Mormon emigration

Following persecution and mob action in Missouri, Illinois, and other states, and the martyrdom of their prophet Joseph Smith in 1844, Mormon leader Brigham Young was chosen by the leaders of the Latter Day Saints (LDS) church to lead the LDS settlers west. He chose to lead his people to the Salt Lake Valley in present-day Utah. In 1847 Young led a small, especially picked fast-moving group of men and women from their Winter Quarters encampments near Omaha, Nebraska, and their approximately 50 temporary settlements on the Missouri River in Iowa including Council Bluffs, Iowa.[19] About 2,200 LDS pioneers went that first year as they filtered in from Mississippi, Colorado, California, and several other states. The initial pioneers were charged with establishing farms, growing crops, building fences and herds, and establishing preliminary settlements to feed and support the many thousands of immigrants expected in the coming years. After ferrying across the Missouri River and establishing wagon trains near what became Omaha, Nebraska, the Mormons followed the northern bank of the Platte River in Nebraska to Fort Laramie in present-day Wyoming. They initially started out in 1848 with trains of several thousand emigrants, which were rapidly split into smaller groups to be more easily accommodated at the limited springs and acceptable camping places on the trail. Organized as a complete evacuation from their previous homes, farms, and cities in Illinois, Missouri, and Iowa, this group consisted of entire families with no one left behind. The much larger presence of women and children meant these wagon trains did not try to cover as much ground in a single day as Oregon and California bound emigrants did — typically taking about 100 days to cover the 1,000 miles (1,600 km) trip to Salt Lake City. (The Oregon and California emigrants typically averaged about 15 miles (24 km) per day.) In Wyoming the Mormon emigrants followed the main Oregon/California/Mormon Trail through Wyoming to Fort Bridger, where they split from the main trail and followed (and improved) the crude path established by the ill-fated Donner Party of 1846 into Utah and the Salt Lake Valley.

Between 1847 and 1860 over 43,000 Mormon settlers and tens of thousands of travelers on the California Trail and Oregon Trail followed Young to Utah. After 1848, the travelers headed to California or Oregon resupplied at the Salt Lake Valley, and then went back over the Salt Lake Cutoff, rejoining the trail near the future Idaho-Utah border at the City of Rocks in Idaho.

Starting in 1855, many of the poorer Mormon travelers made the trek with hand built handcarts and fewer wagons. Guided by experienced guides, handcarts—pulled and pushed by two to four people—were as fast as oxen-pulled wagons and allowed them to bring 75 to 100 pounds (34 to 45 kg) of possessions plus some food, bedding, and tents to Utah. Accompanying wagons carried more food and supplies. Upon arrival in Utah, the handcart pioneers were given or found jobs and accommodations by individual Mormon families for the winter until they could become established. About 3,000 out of over 60,000 Mormon pioneers came across with handcarts.

Along the Mormon Trail, the Mormon pioneers established a number of ferries and made trail improvements to help later travelers and earn much needed money. One of the better known ferries was the Mormon Ferry across the North Platte near the future site of Fort Caspar in Wyoming which operated between 1848 and 1852 and the Green River ferry near Fort Bridger which operated from 1847 to 1856. The ferries were free for Mormon settlers while all others were charged a toll of from $3.00 to $8.00.

California Gold Rush

In January 1848, James Marshall discovered a small nugget of gold in the American River, sparking the California Gold Rush. It is estimated that about two-thirds of the male population in Oregon went to California in 1848 to cash in on the early gold discoveries. To get there, they helped build the Lassen Branch of the Applegate-Lassen Trail by cutting a wagon road through extensive forests. Many returned with significant gold which helped jump-start the Oregon economy. Over the next decade, gold seekers from the Midwestern United States and East Coast of the United States started rushing overland and dramatically increased traffic on the Oregon and California Trails. The "forty-niners" often chose speed over safety and opted to use shortcuts such as the Sublette-Greenwood Cutoff in Wyoming which reduced travel time by almost seven days but spanned nearly 45 miles (72 km) of desert without water, grass, or fuel for fires.[20] 1849 was the first year of large scale cholera epidemics in the United States, and thousands are thought to have died along the trail on their way to California—most buried in unmarked graves in Kansas and Nebraska. The 1850 census showed this rush was overwhelmingly male: the ratio of women to men in California over 16 years was about 1:18.[21] After 1849 the rush continued for several years as the California miners continued to find about $50,000,000 worth of gold per year at $21 per ounce.[22]

Later emigration and uses of the trail

Overall it is estimated that over 400,000 pioneers used the Oregon Trail and its three primary offshoots, the California, Bozeman, and Mormon Trails. The trail was still in use during the Civil War, but traffic declined after 1855 when the Panama Railroad across the Isthmus of Panama was completed. Paddle wheel steamships and sailing ships, often heavily subsidized to carry the mail, provided rapid transport to and from the east coast and New Orleans, Louisiana, to and from Panama to ports in California and Oregon.

Over the years many ferries were established to help get across the many rivers on the path of the Oregon Trail. Multiple ferries were established on the Missouri River, Kansas River, Little Blue River, Elkhorn River, Loup River, Platte River, South Platte River, North Platte River, Laramie River, Green River, Bear River, two crossings of the Snake River, John Day River, Deschutes River, Columbia River, as well as many other smaller streams. During peak immigration periods several ferries on any given river often competed for pioneer dollars. These ferries significantly increased speed and safety for Oregon Trail travelers. They increased the cost of traveling the trail by roughly $30.00 per wagon but increased the speed of the transit from about 160–170 days in 1843 to 120–140 days in 1860. Ferries also helped prevent death by drowning at river crossings.[23]

In April 1859, an expedition of U. S. Army Corps of Topographical Engineers led by Captain James H. Simpson left Camp Floyd (Utah) to establish an army supply route across the Great Basin to the eastern slope of the Sierras. Upon return in early August, Simpson reported that he had surveyed the Central Overland Route from Camp Floyd (Utah) to Genoa, Nevada. This route went through central Nevada (roughly where U.S. Route 50 goes today) and was about 280 miles shorter than the 'standard' Humboldt River California trail route.[24]

The Army improved the trail for use by wagons and stagecoaches in 1859 and 1860. Starting in 1860, the American Civil War closed the heavily subsidized Butterfield Overland Mail stage Southern Route through the deserts of the American Southwest.

In 1860–1861 the Pony Express, employing riders traveling on horseback day and night with relay stations about every ten miles to supply fresh horses, was established from St. Joseph, Missouri, to Sacramento, California. The Pony Express built many of their eastern stations along the Oregon/California/Mormon/Bozeman trails and many of their western stations along the very sparsely settled Central Route across Utah and Nevada.[25] The Pony Express delivered mail summer and winter in roughly ten days from the midwest to California.

In 1861 John Butterfield, who since 1858 had been using the Butterfield Overland Mail, also switched to the Central Route to avoid traveling through hostile territories during the American Civil War. George Chorpenning immediately realized the value of this more direct route, and shifted his existing mail and passenger line along with their stations from the "Northern Route" along the Humboldt River. In 1861 the Transcontinental Telegraph also laid its lines alongside the Central Overland Route. Several stage lines were set up carrying mail and passengers that traversed much of the route of the original Oregon Trail to Fort Bridger and from there over the Central Overland Route to California. By traveling day and night with many stations and changes of teams (and extensive mail subsidies) these stages could get passengers and mail from the midwest to California in about 25–28 days. These combined stage and Pony Express stations along the Oregon Trail and Central Route across Utah and Nevada were joined by the First Transcontinental Telegraph stations and telegraph line which followed much the same route in 1861 from Carson City, Nevada to Salt Lake City, Utah. The Pony Express folded in 1861 as they failed to receive an expected mail contract from the U.S. government and the telegraph filled the need for rapid east-west communication. This combination wagon/stagecoach/pony express/telegraph line route is labeled the Pony Express National Historic Trail on the National Trail Map.[25] From Salt Lake City the telegraph line followed much of the Mormon/California/Oregon trails to Omaha, Nebraska.

After the First Transcontinental Railroad was completed in 1869 all the telegraph lines usually followed the railroad tracks as the required relay stations and telegraph lines were much easier to maintain alongside the tracks. Telegraph lines to unpopulated areas were largely abandoned.

As the years passed the Oregon Trail became a heavily used corridor from the Missouri River to the Columbia River. Offshoots of the trail continued to grow as gold and silver discoveries, farming, lumbering, ranching, and business opportunities resulted in much more traffic to many areas. Traffic became two-directional as towns were established along the trail. By 1870 the population in the states served by the Oregon Trail and its offshoots increased by about 350,000 over their 1860 census levels. With the exception of most of the 180,000 population increase in California, most of these people living away from the coast traveled over parts of the Oregon trail and its many extensions and cutoffs to get to their new residences.

Even before the famous Texas cattle drives after the Civil War, the trail was being used to drive herds of thousands of cattle, horses, sheep, and goats from the midwest to various towns and cities along the trails. According to studies by trail historian John Unruh the livestock may have been as plentiful or more plentiful than the immigrants in many years.[26] In 1852 there were even records of a 1,500 turkey drive from Illinois to California.[27] The main reason for this livestock traffic was the large cost discrepancy between livestock in the midwest and at the end of the trail in California, Oregon, or Montana. They could often be bought in the midwest for about 1/3 to 1/10 what they would fetch at the end of the trail. Large losses could occur and the drovers would still make significant profit. As the emigrant travel on the trail declined in later years and after livestock ranches were established at many places along the trail large herds of animals often were driven along part of the trail to get to and from markets.

Trail decline

The first transcontinental railroad was completed in 1869, providing faster, safer, and usually cheaper travel east and west (the journey took seven days and cost as little as $65).[28] Some emigrants continued to use the trail well into the 1890s, and modern highways and railroads eventually paralleled large portions of the trail, including U.S. Highway 26, Interstate 84 in Oregon and Idaho and Interstate 80 in Nebraska. Contemporary interest in the overland trek has prompted the states and federal government to preserve landmarks on the trail including wagon ruts, buildings, and "registers" where emigrants carved their names. Throughout the 20th and 21st centuries there have been a number of re-enactments of the trek with participants wearing period garments and traveling by wagon.

References

- Federal Writers Project, The Oregon trail: the Missouri river to the Pacific ocean (1839) p. 215

- "Lewis and Clark Pass, Montana".

- "Map of Astorian expedition, Lewis and Clark expedition, Oregon Trail, etc. in Pacific Northwest etc". oregon.com. Archived from the original on 2 February 2009. Retrieved 31 December 2008.

- Rollins, Philip Ashton (1995). The Discovery of the Oregon Trail: Robert Stuart's Narratives of His Overland Trip Eastward from Astoria in 1812–13. University of Nebraska. ISBN 0-8032-9234-1.

- "Fort Colville". Nwcouncil.org. Retrieved 2011-03-19.

- Resettlement maps Archived 2012-01-29 at the Wayback Machine

- Red River Settlers in Oregon Accessed 22 February 2009

- It was not until later that the Ogallala Aquifer was discovered and used for irrigation, dry farming techniques developed and railtracks laid.

- Archived 2009-04-16 at the Wayback Machine IDAHO FUR TRADE

- Gowans, Fred R. Rocky Mountain Rendezvous, pg 27. Gibbs Smith Publisher. ISBN 1-58685-756-8

- The Adventures of Captain Bonneville s:The Adventures of Captain Bonneville accessed 5 January 2009

- Frémont's Map of California and Oregon; Accessed 23 December 2009

- The Oregon History Project: Protestant Ladder. Oregon Historical Society. Retrieved on February 19, 2008.

- Oregon Emigrants 1839

- "Oregon Emigrants 1840". Archived from the original on 2011-06-28. Retrieved 2011-04-16.

- Members of the party later disagreed over the size of the party, one stating 160 adults and children were in the party, while another counted 105.

- The Wagon Train of 1843: The Great Migration. Archived 2008-05-31 at the Wayback Machine Oregon Pioneers. Retrieved December 22, 2007.

- Events in The West: 1840–1850. PBS. Retrieved December 22, 2007.

- Mormons in Iowa towns map "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-07-19. Retrieved 2011-03-19.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) referenced 5 January 2009

- "American West – The Oregon Trail".

- "1850 census Male, female ratio California". Archived from the original on 2011-07-11. Retrieved 2011-04-16.

- Greeley, Horace. An Overland Journey from New York to San Francisco in the Summer of 1859. XXXIV.

- Unruh:op. cit. pp 410

- Simpson, Capt. J. H. (1876). "Report of Explorations across the Great Basin of the Territory of Utah". Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office: 25–26. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Pony Express Trail map Accessed 28 January 2009

- Unruh, John D (1993). The Plains Across the Overland Emigrants and Trans-Mississippi West 1840–1860. University of Illinois Press. pp. 392, 512. ISBN 978-0-252-06360-2.

- Barry, Louise. The Beginnings of the West. 1972. pp 1084–85

- Railroad ticket 1870 Archived 2009-06-24 at the Wayback Machine accessed 21 January 2009