Jim Bridger

James Felix Bridger (March 17, 1804 – July 17, 1881) was an American mountain man, trapper, Army scout, and wilderness guide who explored and trapped in the Western United States in the first half of the 19th century. He was from the Bridger family of Virginia, English immigrants that had been in North America since the early colonial period.[1]

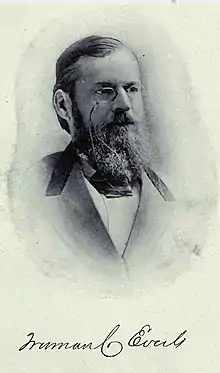

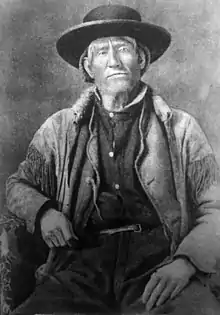

Jim Bridger | |

|---|---|

Bridger c. 1876 | |

| Born | James Felix Bridger March 17, 1804 |

| Died | July 17, 1881 (aged 77) |

| Occupation | Frontiersman, explorer, hunter, trapper, scout, guide |

| Employer | Rocky Mountain Fur Company, U.S. Government |

| Known for | Famous mountain man of the American fur trade era |

| Spouse(s) | Three Native American wives: one Flathead and two Shoshone |

| Children | 5 |

| Relatives | 3 spouses all Native American, one Flathead and two Shoshone |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | |

| Years of service | 1859–1860 |

| Rank | Scout |

| Unit | |

| Commands held | Rifleman |

| Battles/wars | Raynolds Expedition |

Bridger was part of the second generation of American mountain men and pathfinders that followed the Lewis and Clark expedition of 1804 and became well known for participating in numerous early expeditions into the western interior as well as mediating between Native American tribes and westward-migrating European-American settlers. By the end of his life, he had earned a reputation as one of the foremost frontiersmen in the American Old West.

He was described as having a strong constitution that allowed him to survive the extreme conditions he encountered while exploring the Rocky Mountains from what would become southern Colorado to the Canadian border. He had conversational knowledge of French, Spanish, and several indigenous languages.

Bridger was a contemporary of many famous European-American explorers of the early west and would come to know many of them, including Kit Carson, George Armstrong Custer, Hugh Glass, John Frémont, Joseph Meek, John Sutter, Peter Skene Ogden, Jedediah Smith, Robert Campbell, and William Sublette. In 1830, Smith and his associates sold their fur company to Bridger and his associates who named it the Rocky Mountain Fur Company.

Early life and career

James Felix Bridger was born on March 17, 1804, in Richmond, Virginia.[2] His parents were James Bridger, an innkeeper in Richmond, and his wife Chloe.[2] About 1812, the family moved near to St. Louis at the eastern edge of America's vast new western frontier.[2] At the age of 13, Bridger was orphaned. James Bridger had no formal education, unable to read or write, he was apprenticed to a blacksmith.[3] He was illiterate the whole of his life.[3] On March 20, 1822, at the age of 18, he left his apprenticeship after responding to an advertisement in a St. Louis newspaper, the Missouri Republican, and joined General William Henry Ashley's fur trapping expedition to the upper Missouri River. The party included Jedediah Smith and many others who would later become famous mountain men.[2] For the next 20 years, he repeatedly traversed the continental interior between the Canada–U.S. border and the southern boundary of present-day Colorado, and from the Missouri River westward to Idaho and Utah, either as an employee of or a partner in the fur trade.[2]

Hugh Glass ordeal

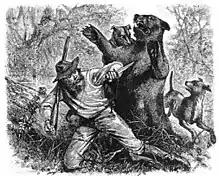

Bridger continued his employment with Ashley's fur trapping venture for several seasons. On June 2, 1823, Ashley's men were attacked by Arikara warriors along the Missouri River. Fifteen men were killed and the rest of the fur trappers fled down the river and hid in shelters until U.S. military support defeated the Arikara. In August 1823, near the forks of the Grand River in present-day Perkins County, South Dakota while scouting for game for the expedition's larder, Hugh Glass surprised a grizzly bear with two cubs. The bear charged, picked him up and threw him to the ground. He killed the bear with help from the other trappers, but was left badly mauled and unconscious. Ashley asked for two volunteers to stay with Glass until he died and to then bury him. John Fitzgerald and a man known as 'Bridges' stepped forward and as the rest of the party moved on, began digging Glass's grave. Later, claiming they were interrupted by an Arikara attack, the pair grabbed Glass's rifle, knife, and other equipment and took flight. Bridges and Fitzgerald later caught up with the party and incorrectly reported to Ashley that Glass had died.[4]

Despite his injuries, Glass regained consciousness. After recovering, Glass set out again to find Fitzgerald and Bridges, motivated either by murderous revenge or the desire to get his weapons back. He eventually found Bridges at the mouth of the Bighorn River, but apparently forgave him because of his youth.[5] Glass also found Fitzgerald and reportedly spared his life because of the penalty for killing a soldier of the United States Army.

Contemporary accounts list John Fitzgerald and a man only identified as 'Bridges' as the two volunteers to stay with Glass. Jim Bridger was only imprecisely identified as present 73 years later in 1896, and this report was repeated in 1953. This account of the desertion of Hugh Glass has been repeated by many, but it is of dubious origin that Jim Bridger was involved at all.[6]

Yellowstone and the Great Salt Lake

Bridger was among the first North American-born Colonial Frontiersmen to see the geysers and other natural wonders of the Yellowstone region. In the winter of 1824–1825, Bridger gained fame as the first European American to see the Great Salt Lake (though some now dispute that status in favor of contemporary explorer Étienne Provost), which he reached traveling in a bull boat. Due to its saltiness, Bridger believed it to be an arm of the Pacific Ocean. Historians are unsure if he was alone when he found the Great Salt Lake.

Guide and adviser

Bridger had explored, trapped, hunted and blazed new trails in the West since 1822, and later worked as a wilderness guide in these areas. He could reportedly assess any wagon train or group, their interests in travel, and give them expert advice on any and all aspects of heading West, over any and all trails, and to any destination the party had in mind, if the leaders sought his advice. In 1846, the Donner Party came to Fort Bridger and were assured by Bridger and Vasquez that Lansford Hastings' proposed shortcut ahead was "a fine, level road, with plenty of water and grass, with the exception before stated (a forty-mile waterless stretch)." The 40-mile stretch was in fact 80 miles, and the "fine level road" was difficult enough to slow the Donner Party, who become trapped in the Sierra Nevada in the winter.

In 1859, Bridger was paid to be the chief guide on the Yellowstone-bound Raynolds Expedition, led by Captain William F. Raynolds. Bridger guided the expedition over Union Pass after finding that mountain passes to the north were blocked by snow. Though unsuccessful in reaching the Yellowstone Plateau, the expedition explored Jackson Hole and the Teton Range.

Bridger Pass and the Bridger Trail

In 1850, while guiding the Stansbury Expedition on its return from Utah, Bridger discovered what would eventually become known as Bridger Pass, an alternate overland route which bypassed South Pass and shortened the Oregon Trail by 61 miles. Bridger Pass, in what is now south-central Wyoming, would later become the chosen route across the Continental Divide for both the Union Pacific Railroad and Interstate 80.

In 1864, Bridger blazed the Bridger Trail, an alternative route from Wyoming to the gold fields of Montana that avoided the dangerous Bozeman Trail. In 1865, he served as a guide and U.S. Army scout during the first Powder River Expedition against the Sioux and Cheyenne that were blocking the Bozeman Trail (Red Cloud's War). He was discharged from the Army at Fort Laramie later that year. Suffering from goiter, arthritis, rheumatism and other health problems, Bridger returned to Westport, Missouri, in 1868. He was unsuccessful in collecting back rent from the government for its use of Fort Bridger.

Marriages, Indian wives, and family

In 1835, Bridger married a woman [7] from the Flathead Indian tribe that he named "Emma", with whom he had three children. After her death in 1846, due to fever, he married the daughter of a Shoshone chief, who died in childbirth three years later. In 1850, he married Shoshone chief Washakie's daughter, and they raised two more children. Some of his children were sent back east to be educated. His firstborn Mary Ann was killed by a band of Indians while being taught by Dr. Whitman's wife. His son Felix, who fought with the Missouri Artillery, died of sickness on Bridger's farm. His daughter Josephine, who married Jim Baker, also died, leaving his daughter Virginia as his only living child. [8]

Death

Bridger died on his farm near Kansas City, Missouri, on July 17, 1881, at the age of 77. In the Independence Missouri School District, a junior high and then the middle school which replaced it are named after him.

Legacy

Historical reputation

Bridger is remembered as one of the most colorful and widely traveled mountain men of the era. In addition to his explorations and his service as a guide and adviser, he was known for his storytelling. His stories about the geysers at Yellowstone, for example, proved to be true. Others were grossly exaggerated or clearly intended to amuse: one of Bridger's stories involved a petrified forest in which there were "petrified birds" singing "petrified songs" (though he may have seen the petrified trees in the Tower Junction area of what is now Yellowstone National Park). Over the years, Bridger became so associated with telling tall tales that many stories invented by others were attributed to him.

Supposedly one of Bridger's favorite yarns to weave to greenhorns told of his pursuit by one hundred Cheyenne warriors. After being chased for several miles, Bridger found himself at the end of a box canyon, with the Indians bearing down on him. At this point, Bridger would go silent, prompting his listener to ask, "What happened then, Mr. Bridger?" Bridger would then reply, "They killed me." Bridger's tale was similar to the actual death of Jedediah Smith, who had died under the lances of Comanche Indians on the Santa Fe Trail in 1831.

Places and things named for Jim Bridger

- Fort Bridger

- Fort Bridger, Wyoming

- Bridger, Montana

- Bridger Bay, Utah,[9] a bay in the Great Salt Lake at Antelope Island

- Bridger Bay Beach, Utah,[10] a beach on Antelope Island in the Great Salt Lake

- Bridger Mountains (Wyoming)

- Bridger Mountains (Montana)

- Bridger Peak in Utah

- Bridger Pointe, a neighborhood complex in Logan, Utah

- Bridger Wilderness

- Bridger Bowl Ski Area

- Bridger-Teton National Forest

- Bridger Pass

- Bridger Center and Bridger Gondola at Jackson Hole Mountain Resort, Teton Village, WY.

- Jim Bridger Power Station

- Bridger Lake, a lake and campground near Mountain View, Wyoming[11]

- Bridgerland in Cache Valley in Utah and Idaho is a name that is used in many Logan, Utah-based businesses and institutions, such as Bridgerland Television and the Bridgerland Technical College.

- Bridgerland Park, a city park in Logan, Utah

- James Bridger Middle School in Independence, Missouri

- Jim Bridger Drive, Centerville, Utah

- Jim Bridger Drive, Eagle Mountain, Utah

- Jim Bridger Drive, Huntsville, Utah

- Jim Bridger Elementary School in Portland, Oregon

- Jim Bridger Elementary School in West Jordan, Utah

- Jim Bridger Trail Run outside Bozeman, Montana

- Bridger Avenue in Las Vegas, Nevada

- Bridger Drive in Logan, Utah

- Bridger Drive in Springville, Utah

- Bridger Road in Salt Lake City, Utah

- Bridger Street in Pocatello, Idaho

- The Jim Bridger cabins, a motel in Gardiner, Montana, outside the entrance to Yellowstone National Park.

- In 2013, Bridger's Battle was announced as the new name for an old college football rivalry between Utah State and Wyoming. The winner receives a .50-caliber Rocky Mountain Hawken rifle, the "Bridger rifle", as a traveling trophy.

Media portrayals

- Raymond Hatton portrayed Bridger in the 1940 film Kit Carson.

- Van Heflin played Bridger in the 1951 film Tomahawk.

- Dennis Morgan portrayed Bridger in the 1955 film The Gun That Won the West.

- In the late 1950s, Johnny Horton recorded a song called "Jim Bridger" about the life of Jim Bridger. Lyrics include the injunction "..Let's drink to old Jim Bridger yes, lift your glasses high" – "As long as there's a USA don't let his memory die" – "That he was making history never once occurred to him" – "But I doubt if we'd have been here if it weren't for men like Jim..."[12]

- Harry Shannon was cast as Bridger in the 1958 episode, "Old Gabe," referring to a Bridger nickname, on the syndicated anthology series, Death Valley Days, hosted by Stanley Andrews. Ron Hagerthy played Bridger's grown son, Felix. In the story line, the aging Bridger returns home to Missouri to find that his wife has died in childbirth, and Felix is trying to keep their farm despite an unpaid mortgage. Despite his failing eyesight, Bridger sets out on a last scouting expedition to make peace with the Sioux and thereby raise funds to retire the mortgage. Roy Engel played the part of Colonel Henry B. Carrington, who hires Bridger on the scout's last expedition in 1866.[13]

- Carl Reindel played Jim Bridger in the 1966 Death Valley Days episode, episode, "Hugh Glass Meets the Bear", hosted by Ronald Reagan. The episode is the story of trapper Hugh Glass (John Alderson), who was mauled by a bear, left for dead, but survived by crawling two hundred miles to safety. Others in the episode were Morgan Woodward as trapper Thomas Fitzpatrick, Victor French as Louis Baptiste, and Tris Coffin as Major Andrew Henry.[14]

- Karl Swenson played Bridger in the episode "The Jim Bridger Story" of NBC's Wagon Train, broadcast on May 10, 1961.

- Jim Bridger is also briefly mentioned in Sydney Pollack's 1972 film Jeremiah Johnson, in which Will Geer's character introduces himself as "Bear Claw Chris Lapp, blood kin to the grizz (grizzly bear) that bit Jim Bridger's ass."

- James Wainwright played Bridger in the 1976 TV movie Bridger, opposite Ben Murphy as Kit Carson.

- Bridger was portrayed on television by the western actor Gregg Palmer in the 1977 episode "Kit Carson and the Mountain Man" of NBC's Walt Disney's Wonderful World of Color. Christopher Connelly portrayed Kit Carson and Robert Reed played John C. Frémont.

- Reb Brown portrayed Bridger in the 1978 TV miniseries Centennial.

- In the 1982 novel Flashman and the Redskins, lead character Harry Paget Flashman is interviewed by Bridger just before heading west with his prostitute-laden wagon train.

- In the 1984 film Red Dawn, Patrick Swayze's character of Jed Eckert says he used to read of the exploits of both Jim Bridger and Jedediah Smith, for whom he says he was named.

- In Bushcraft, the 2005 televised series hosted by Ray Mears, Ray traveled along the same trails Jim Bridger pioneered.

- In the 2009 film Inglourious Basterds, lead character Lt. Aldo Raine (portrayed by Brad Pitt) states: "Now, I am the direct descendant of the mountain man Jim Bridger. That means I got a little Injun in me. And our battle plan will be that of an Apache resistance." None of Bridger's three Indian wives were Apache.

- In the 2015 film The Revenant, Will Poulter portrays Bridger.

See also

- Bridger family of Virginia, notable to American colonial and pioneer history

- Joseph Bridger, a Colonial Governor of Virginia and ancestor of Jim Bridger

- William Sublette, explorer, fur trader, and fellow mountain man of Wyoming

- Monumental Mysteries

References

- Fischer, David Hackett (1989). Albion's Seed: Four British Folkways in America. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 633–639. ISBN 978-0-19-506905-1.

- Dale 1929, p. 33.

- Dale 1929, pp. 33–34.

- "Did Jim Bridger Abandon Hugh Glass". HughGlass.org/. Museum of the Mountain Man. Retrieved December 18, 2015.

- "Biographical Notes – Hugh Glass". Wandering Lizard History. Archived from the original on 8 May 2006. Retrieved 4 October 2015.

- http://hughglass.org/jim-bridger/

- Jim Bridger Greatest Of The Mountain Men Shannon Garst 1952

- Jim Bridger Greatest Of The Mountain Men Shannon Garst 1952

- https://www.outdoorproject.com/united-states/utah/bridger-bay-beach-day-use-area

- https://www.outdoorproject.com/united-states/utah/bridger-bay-beach-day-use-area

- "Uinta-Wasatch-Cache National Forest – Bridger Lake Campground".

- "Jim Bridger Lyrics – Song by Johnny Horton".

- "Old Gabe on Death Valley Days". Internet Movie Data Base. Retrieved September 4, 2018.

- "Hugh Glass Meets the Bear on Death Valley Days". Internet Movie Data Base. March 24, 1966. Retrieved September 20, 2015.

Sources

- Dale, Harrison Clifford (1929). Allen Johnson (ed.). Dictionary of American Biography Bridger, James. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons.

Further reading

- Alter, J. Cecil (1951), James Bridger Trapper, Frontiersman, Scout And Guide A Historical Narrative, College Book Co.

- Caesar, Gene (1961), King Of The Mountain Men, E.P. Dutton Co

- Vestal, Stanley (1946), Jim Bridger Mountain Man, William Morrow & Company

- "Affidavit discussing Jim Bridger's property and Fort Bridger"

- Jim Bridger in Idaho