Homer Watson

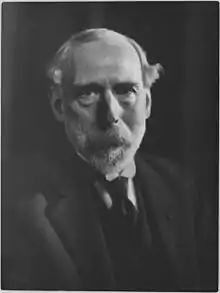

Homer Ransford Watson RCA (January 14, 1855 – May 30, 1936) was a Canadian landscape painter. He has been characterized as the painter who first painted Canada as Canada, rather than as a pastiche of European painting.[1] He was a member and president (1918–1922) of the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts, as well as a founding member and first president (1907–1911) of the Canadian Art Club.[1] Although Watson had almost no formal training, by his mid-1920s he was well known and admired by Canadian collectors and critics, his rural landscape paintings making him one of the central figures in Canadian art from the 1880s until the First World War.[1]

Homer Watson | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Homer Ransford Watson January 14, 1855 |

| Died | May 27, 1936 (aged 81) Doon, Ontario, Canada |

| Nationality | Canadian |

| Known for | Painting |

Notable work | The Flood Gate (1900) |

| Movement | Barbizon School |

Life and career

The son of Ransford Watson and Susan Mohr, Homer Watson was born on January 14, 1855 in the village of Doon (now part of Kitchener), Ontario. His parents who owned a mill and factory, had a library of books and Watson may have copied engravings and illustrations from them as a youngster.[2]:44 A gift of a set of paints from an aunt made him decide to become an artist. He sought the advice of Thomas Mower Martin in Toronto, and moved there in 1874.[2]:44 He copied works at the Toronto Normal School and was mainly self-taught, but met other artists in Toronto (e.g., Lucius O'Brien) while working part-time at the Notman-Fraser photography studio.

In 1876, Watson traveled to New York State, and may have seen the work of painter George Inness.[1] Although he never met Inness, he was influenced by the Hudson River School and painted along the Hudson and Susquehanna Rivers in the Adirondack Mountains.[1] In 1880, the Marquis of Lorne opened the first exhibition of the Canadian Academy; Watson's work was displayed and he was elected an Associate member.[1] That same year, he sold a major work, The Pioneer Mill, to the Marquis for Queen Victoria.[1]

Watson married Roxanna (Roxa for short) Bechtel in 1881, and the couple moved into the Drake House at Doon.[1] They bought the house in 1883, and he kept the house as his permanent residence until his death. Watson painted the rural Grand River countryside for most of his artistic life.[1] He was noted for his commitment to Canadian landscapes: he said at a lecture on "The Methods of Some Great Landscape Painters" at the University of Toronto in 1900: "there is at the bottom of each artistic conscience a love for the land of their birth... no immortal work has been done which has not as one of its promptings for its creation a feeling its creator had of having roots in his native land and being a product of its soil".[3]

The artists with whom Watson was most often associated were the English landscape painter John Constable (1776–1837) and such French Barbizon artists as Théodore Rousseau (1812–1867), Charles-François Daubigny (1817–1878), Narcisse Díaz de la Peña (1807–1876), Constant Troyon (1810–1865), Jules Dupré (1811–1889), and tangentially Jean-François Millet (1814–1875) because Watson didn`t share Millet`s focus on the nobility of human figures.[1] The thematic, formal, and psychological similarities between Watson, John Constable, and the Barbizon artists were strong. They were emotionally and psychologically devoted to landscapes with whose topography and inhabitants they were intimately familiar.[1]

In 1882, while touring Canada, Oscar Wilde first noted the similarity between Watson and Constable, dubbing him the "Canadian Constable" due to the similarity between Watson's work and of the great English landscape painter.[1] Wilde and Watson may have met at public events.[1] There may have been letters between the two men which could be in a private collection or lost.

Watson moved to England in 1887 for three years (1887–1890), and further established his reputation.[1] Over the next few years, his works became increasingly popular among collectors and received prizes at expositions across North America. In 1902, at the height of his British career, he exhibited The Flood Gate.

He campaigned to save the Waterloo County woodlands that he had preserved in his landscapes. Due to the Stock Market Crash of 1929 in which he lost his savings, he was forced to hand over many works from his personal collection to the local savings & loans firm, which held them for security and then tried to sell the paintings itself.[1]

Homer Watson died in Doon on May 30, 1936.[4]

Legacy

Many of Watson's works are still on display at his old house, which he and his sister had transformed into a small art gallery. Homer Watson's letters, his unpublished manuscripts, and his paintings, drawings, and prints document the issues that most interested him as an artist. Of his concerns, the commemoration of southern Ontario's pioneers and early settlers and the visual expression of Canadian regional and national identities locate Watson firmly within the milieu of many of his fellow artists of the time. In addition to these priorities, his dedication to safeguarding the natural environment was exceptional and far-sighted.[1]

On May 27, 2005, Canada Post issued a pair of postage stamps in his honour. Two stamps of denominations 50 and 85 cents were issued depicting two of his works, Dawn in the Laurentides and The Flood Gates.[5] An arterial road in Kitchener, which connects the Doon area to the main parts of the city, is named Homer Watson Boulevard.

Watson has been designated a Person of National Historic Significance in Canada. Watson's former house in Doon, now the Doon School of Fine Arts, was designated a National Historic Site of Canada in 1980.[6][7]

Selected works

Old Mill and Stream 1879

Old Mill and Stream 1879 The Castellated Cliff 1879

The Castellated Cliff 1879 The Stone Road 1881

The Stone Road 1881 Down in the Laurentides 1882

Down in the Laurentides 1882 Near the Close of a Stormy Day 1884

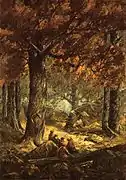

Near the Close of a Stormy Day 1884 Nut Gatherers in the Forest 1900

Nut Gatherers in the Forest 1900 Rushing Stream by Moonlight 1905

Rushing Stream by Moonlight 1905 Pink Bush 1906

Pink Bush 1906 Study for Red Oak 1917

Study for Red Oak 1917 Moonlight, Waning Winter 1924

Moonlight, Waning Winter 1924 Mountain River 1932

Mountain River 1932

References

- Foss, Brian (2018). Homer Watson: Life & Work. Toronto: Art Canada Institute. ISBN 978-1-4871-0185-5.

- Watson, Jennifer C. (1987). "Homer Watson in the Kitchener-Waterloo Art Gallery". RACAR: Revue d'art canadienne / Canadian Art Review. 14 (1/2): 143–150. ISSN 0315-9906. JSTOR 42630360.(subscription may be required or content may be available in libraries)

- Foss, Brian (2010). Into the New Century: Painting, c.1880-1914, The Visual Arts in Canada: The Twentieth Century. Canada: Oxford. pp. 22, n.6 who quotes from Appendix 1 of Gerald Noonan, Refining the Real Canada: Homer Watson's Spiritual Landscape. Waterloo: mlr editions canada, 1997. Retrieved 2020-09-04.

- Harper, J. Russell (25 May 2008). "Homer Ransford Watson". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Historica Canada. Retrieved 29 March 2017.

- "Art Canada: Homer Watson (1855-1936)". Canada Post. Archived from the original on 17 October 2013. Retrieved 13 October 2013.

- Homer Watson House / Doon School of Fine Arts, Directory of Designations of National Historic Significance of Canada

- Homer Watson House / Doon School of Fine Arts, National Register of Historic Places

Bibliography

- Foss, Brian. Homer Watson: Life & Work. Toronto: Art Canada Institute, 2018. ISBN 978-1-4871-0185-5

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Homer Watson. |

- Homer Watson: not your average pastoral picnic: selections from the permanent collection. Kitchener, Ontario, Canada: Kitchener-Waterloo Art Gallery. 2005.

- Miller, Muriel (1938). Homer Watson: the man of Doon. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: Summerhill Press.

External links

- Homer Watson House & Gallery

- Biography at Mount Allison University

- Virtual Museum on Homer Watson

- London Ontario Museum on Homer Watson

- University of Waterloo Library Holdings on Homer Watson

- Finding aid, Homer Watson fonds, National Gallery of Canada Library and Archives

| Cultural offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by William Brymner |

President of the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts 1918-1922 |

Succeeded by George Horne Russell |