Hyponymy and hypernymy

In linguistics, hyponymy (from Greek ὑπό, hupó, "under", and ὄνυμα, ónuma, "name") is a semantic relation between a hyponym denoting a subtype and a hypernym or hyperonym denoting a supertype. In other words, the semantic field of the hyponym is included within that of the hypernym.[1] In simpler terms, a hyponym is in a type-of relationship with its hypernym. For example: pigeon, crow, eagle, and seagull are all hyponyms of bird, their hypernym; which itself is a hyponym of animal, its hypernym.[2]

Hypernymy or hyperonymy (from Greek ὑπέρ, hupér, "over", and ὄνυμα, ónuma, "name") is the converse of hyponymy.

Other names for hypernym include umbrella term and blanket term.[3][4][5][6] A synonym of co-hyponym based on same tier (and not hyponymic) relation is allonym (which means "different name").

A hyponym refers to a type. A meronym refers to a part. For example, a hyponym of tree is pine tree or oak tree (a type of tree), but a meronym of tree is bark or leaf (a part of tree).

Hyponyms and hypernyms

Hyponymy shows the relationship between a generic term (hypernym) and a specific instance of it (hyponym). A hyponym is a word or phrase whose semantic field is more specific than its hypernym. The semantic field of a hypernym, also known as a superordinate, is broader than that of a hyponym. An approach to the relationship between hyponyms and hypernyms is to view a hypernym as consisting of hyponyms. This, however, becomes more difficult with abstract words such as imagine, understand and knowledge. While hyponyms are typically used to refer to nouns, it can also be used on other parts of speech. Like nouns, hypernyms in verbs are words that refer to a broad category of actions. For example, verbs such as stare, gaze, view and peer can also be considered hyponyms of the verb look, which is their hypernym.

Hypernyms and hyponyms are asymmetric. Hyponymy can be tested by substituting X and Y in the sentence "X is a kind of Y" and determining if it makes sense.[7] For example, "A screwdriver is a kind of tool" makes sense, but not "A tool is a kind of screwdriver".

Strictly speaking, the meaning relation between hyponyms and hypernyms applies to lexical items of the same word class (or parts of speech), and holds between senses rather than words. For instance, the word screwdriver used in the previous example refers to the tool for turning a screw, and not to the drink made with vodka and orange juice.

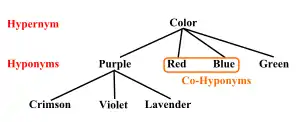

Hyponymy is a transitive relation, if X is a hyponym of Y, and Y is a hyponym of Z, then X is a hyponym of Z.[8] For example, violet is a hyponym of purple and purple is a hyponym of color; therefore violet is a hyponym of color. A word can be both a hypernym and a hyponym: for example purple is a hyponym of color but itself is a hypernym of the broad spectrum of shades of purple between the range of crimson and violet.

The hierarchical structure of semantic fields can be mostly seen in hyponymy. They could be observed from top to bottom, where the higher level is more general and the lower level is more specific. For example, living things will be the highest level followed by plants and animals, and the lowest level may comprise dog, cat and wolf.[9]

Under the relations of hyponymy and incompatibility, taxonomic hierarchical structures too can be formed. It consists of two relations; the first one being exemplified in "An X is a Y" (simple hyponymy) while the second relation is "An X is a kind/type of Y". The second relation is said to be more discriminating and can be classified more specifically under the concept of taxonomy.[10]

Co-hyponyms

If the hypernym Z consists of hyponyms X and Y, X and Y are identified as co-hyponyms. Co-hyponyms are labelled as such when separate hyponyms share the same hypernym but are not hyponyms of one another, unless they happen to be synonymous.[7] For example, screwdriver, scissors, knife, and hammer are all co-hyponyms of one another and hyponyms of tool, but not hyponyms of one another: *"A hammer is a type of knife" is false.

Co-hyponyms are often but not always related to one another by the relation of incompatibility. For example, apple, peach and plum are co-hyponyms of fruit. However, an apple is not a peach, which is also not a plum. Thus, they are incompatible. Nevertheless, co-hyponyms are not necessarily incompatible in all senses. A queen and mother are both hyponyms of woman but there is nothing preventing the queen from being a mother.[11] This shows that compatibility may be relevant.

Autohyponyms

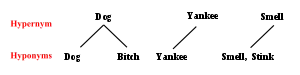

A word is an autohyponym if it is used for both a hypernym and its hyponym.[12] For example, the word dog describes both the species Canis familiaris and male individuals of Canis familiaris, so it is possible to say "That dog isn't a dog, it's a bitch" ("That hypernym Z isn't a hyponym Z, it's a hyponym Y"). The term "autohyponym" was coined by linguist Laurence R. Horn in a 1984 paper, Ambiguity, negation, and the London School of Parsimony. Linguist Ruth Kempson had already observed that if there are hyponyms for one part of a set but not another, the hypernym can complement the existing hyponym by being used for the remaining part. For example, fingers describe all digits on a hand, but the existence of the word thumb for the first finger means that fingers can also be used for "non-thumb digits on a hand".[13] Autohyponymy is also called "vertical polysemy".[lower-alpha 1][14]

Horn called this "licensed polysemy", but found that autohyponyms also formed even when there is no other hyponym. Yankee is autohyponymous because it is a hyponym (native of New England) and its hypernym (native of the United States), even though there is no other hyponym of Yankee (as native of the United States) that means "not a native of New England".[lower-alpha 2][13] Similarly, the verb to drink (a beverage) is a hypernym for to drink (an alcoholic beverage).[13]

In some cases, autohyponyms duplicate existing, distinct hyponyms. The hypernym "smell" (to emit any smell) has a hyponym "stink" (to emit a bad smell), but is autohyponymous because "smell" can also mean "to emit a bad smell", even though there is no "to emit a smell that isn't bad" hyponym.[13]

Hyperonym or hypernym

Both hyperonym and hypernym are in use in linguistics. The form hypernym takes the -o- of hyponym as a part of hypo in the same way as in the contrast between hypertension and hypotension. However, etymologically the -o- is part of the Greek stem ónoma. In other combinations with this stem, e.g. synonym, it is never elided. Therefore, hyperonym is etymologically more faithful than hypernym.[15] Hyperonymy is used, for instance, by John Lyons, who does not mention hypernymy and prefers superordination.[16] The nominalization hyperonymy is rarely used, because the neutral term to refer to the relationship is hyponymy. A practical reason to prefer hyperonym is that hypernym is in its spoken form hard to distinguish from hyponym in most dialects of English.

Usage

Computer science often terms this relationship an "is-a" relationship. For example, the phrase "Red is-a color" can be used to describe the hyponymic relationship between red and color.

Hyponymy is the most frequently encoded relation among synsets used in lexical databases such as WordNet. These semantic relations can also be used to compare semantic similarity by judging the distance between two synsets and to analyse anaphora.

As a hypernym can be understood as a more general word than its hyponym, the relation is used in semantic compression by generalization to reduce a level of specialization.

The notion of hyponymy is particularly relevant to language translation, as hyponyms are very common across languages. For example, in Japanese the word for older brother is ani (兄), and the word for younger brother is otōto (弟). An English-to-Japanese translator presented with a phrase containing the English word brother would have to choose which Japanese word equivalent to use. This would be difficult, because abstract information (such as the speakers' relative ages) is often not available during machine translation.

See also

- Contrast set

- Has-a

- Is-a

- Genus proximum

- Meronymy and holonymy

- -onym

- Polysemy

- Subcategory

- Synonym

- Taxonomy

- WordNet (a semantic lexicon for the English language, which puts words in semantic relations to each other, mainly by using the concepts hypernym and hyponym)

Notes

- In part because the term autohyponymy is ambiguous because it is itself an autohyponym (see Koskela)

- Horn identifies up to four layers of hyponym for Yankee: native of the United States, native of the northern United States, native of New England, or WASP native of New England.

References

- Brinton, Laurel J. (2000). The Structure of Modern English: A Linguistic Introduction (Illustrated ed.). John Benjamins Publishing Company. p. 112. ISBN 978-90-272-2567-2.

- Fromkin, Victoria; Robert, Rodman (1998). Introduction to Language (6th ed.). Fort Worth: Harcourt Brace College Publishers. ISBN 978-0-03-018682-0.

- "Umbrella Term Law and Legal Definition". uslegal.com. Retrieved December 11, 2018.

Umbrella term is also called a hypernym

- Alexander Dhoest (2016). LGBTQs, Media and Culture in Europe. Taylor & Francis. p. 165. ISBN 9781317233138. Retrieved December 11, 2018.

Hypernym can also be called an "Umbrella term"

- Robert J. Sternberg (2011). Handbook of Intellectual Styles. Springer Publishing Company. p. 73. ISBN 9780826106681. Retrieved December 11, 2018.

umbrealla term, or hypernym

- Frank W. D. Röder (2011). The Roeder Protocol. Books on Demand. p. 77. ISBN 9783842351288. Retrieved December 11, 2018.

Synaptic plasticity is a hypernym (umbrella term)

- Maienborn, Claudia; von Heusinger, Klaus; Portner, Paul, eds. (2011). Semantics: An International Handbook of Natural Language Meaning. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton. ISBN 978-3-11-018470-9.

- Lyons, John (1977). Semantics. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-52-129165-1.

- Gao, Chunming; Xu, Bin (November 2013). "The Application of Semantic Field Theory to English Vocabulary Learning". Theory and Practice in Language Studies. 3 (11): 2030–2035. doi:10.4304/tpls.3.11.2030-2035. Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- Green, Rebecca; Bean, Carol A.; Sung, Hyon Myaeng (2002). The Semantics of Relationships: An Interdisciplinary Perspective. Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers. p. 12. ISBN 9781402005688. Retrieved 2014-10-17.

- Cruse, D. A. (2004). Meaning in Language: An Introduction to Semantics and Pragmatics (PDF) (2 ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 162. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-10-17. Retrieved 2014-10-17.

- Gillon, Brendan S. (1990). "Ambiguity, generality, and indeterminacy: Tests and definitions". Synthese. 85 (3): 391–416. doi:10.1007/BF00484835. JSTOR 20116854. S2CID 15186368.

- Horn, Laurence R (1984). "Ambiguity, negation, and the London School of Parsimony". p. 110–118.

- Koskela, Anu (2015-01-23). "On the distinction between metonymy and vertical polysemy in encyclopaedic semantics" (PDF). www.sussex.ac.uk. Retrieved 2019-06-12.

- http://euralex.org/wp-content/themes/euralex/proceedings/Euralex%202018/118-4-2974-1-10-20180820.pdf

- Lyons, John (1977), Semantics, Vol. 1, p. 291

Sources

- Snow, Rion; Daniel Jurafsky; Andrew Y. Ng (2004). "Learning syntactic patterns for automatic hypernym discovery" (PDF). Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems. 17.

- Hearst, M. (1992). "Automatic acquisition of hyponyms from large text corpora". Proceedings of 14th International Conference on Computational Linguistics. 2: 539. doi:10.3115/992133.992154.

External links

| Look up hyponymy, hypernymy, or hyperonymy in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Hypernym at Everything2.com