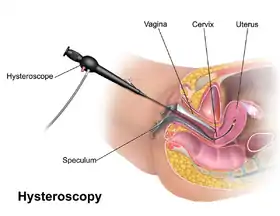

Hysteroscopy

Hysteroscopy is the inspection of the uterine cavity by endoscopy with access through the cervix. It allows for the diagnosis of intrauterine pathology and serves as a method for surgical intervention (operative hysteroscopy).

| Hysteroscopy | |

|---|---|

Anatomic depiction of a modern hysteroscopic procedure. | |

| ICD-9-CM | 68.12 |

| MeSH | D015907 |

| OPS-301 code | 1-672 |

Hysteroscope

A hysteroscope is an endoscope that carries optical and light channels or fibers. It is introduced in a sheath that provides an inflow and outflow channel for insufflation of the uterine cavity. In addition, an operative channel may be present to introduce scissors, graspers or biopsy instruments.[1] A hysteroscopic resectoscope is similar to a transurethral resectoscope and allows entry of an electric loop to shave off tissue, for instance to eliminate a fibroid. [1][2] A contact hysteroscope is a hysteroscope that does not use distention media.

Procedure

Hysteroscopy has been carried out in hospitals, surgical centers and doctors' offices. It is best carried out when the endometrium is relatively thin, that is after a menstruation. Both diagnostic and simple operative hysteroscopy can be carried out in an office or clinic setting on suitably selected patients. Local anesthesia can be used. Analgesics are not always necessary. A paracervical block may be achieved using a Lidocaine injection in the upper part of the cervix. Hysteroscopic intervention can also be done under general anesthesia (endotracheal or laryngeal mask) or Monitored Anesthesia Care (MAC). Prophylactic antibiotics are not necessary. The patient is in a lithotomy position during the procedure. [3]

Cervical dilation

The diameter of the modern hysteroscope is generally small enough to conveniently pass the cervix directly. For a proportion of women cervical dilation may need to be performed prior to insertion. Cervical dilation can be performed by temporarily stretching the cervix with a series of dilators of increasing diameter.[4] Misoprostol prior to hysteroscopy for cervical dilation appears to facilitate an easier and uncomplicated procedure only in premenopausal women.[5]

Insertion and inspection

The hysteroscope with its sheath is inserted transvaginally guided into the uterine cavity, the cavity insufflated, and an inspection is performed.

Insufflation Media

The uterine cavity is a potential cavity and needs to be distended to allow for inspection. Thus, during hysteroscopy, either fluids or CO2 gas is introduced to expand the cavity. The choice is dependent on the procedure, the patient’s condition, and the physician's preference. Fluids can be used for both diagnostic and operative procedures. However, CO2 gas does not allow the clearing of blood and endometrial debris during the procedure, which could make the imaging visualization difficult. Gas embolism may also arise as a complication. Since the success of the procedure is totally dependent on the quality of the high-resolution video images in front of the surgeon's eyes, CO2 gas is not commonly used as the distention medium.

Electrolytic solutions include normal saline and lactated Ringer’s solution. Current recommendation is to use the electrolytic fluids in diagnostic cases, and in operative cases in which mechanical, laser, or bipolar energy is used. Since they conduct electricity, these fluids should not be used with monopolar electrosurgical devices. Non-electrolytic fluids eliminate problems with electrical conductivity, but can increase the risk of hyponatremia. These solutions include glucose, glycine, dextran (Hyskon), mannitol, sorbitol and a mannitol/sorbital mixture (Purisol). Water was once used routinely, however, problems with water intoxication and hemolysis discontinued its use by 1990. Each of these distention fluids is associated with unique physiological changes that should be considered when selecting a distention fluid. Glucose is contraindicated in patients with glucose intolerance. Sorbitol metabolizes to fructose in the liver and is contraindicated if a patient has fructose malabsorption.

High-viscous Dextran also has potential complications which can be physiological and mechanical. It may crystallize on instruments and obstruct the valves and channels. Coagulation abnormalities and adult respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) have been reported. Glycine metabolizes into ammonia and can cross the blood brain barrier, causing agitation, vomiting and coma. Mannitol 5% should be used instead of glycine or sorbitol when using monopolar electrosurgical devices. Mannitol 5% has a diuretic effect and can also cause hypotension and circulatory collapse. The mannitol/sorbitol mixture (Purisol) should be avoided in patients with fructose malabsorption.

When fluids are used to distend the cavity, care should be taken to record its use (inflow and outflow) to prevent fluid overload and intoxication of the patient.[6]

Interventional procedures

If abnormalities are found, an operative hysteroscope with a channel to allow specialized instruments to enter the cavity is used to perform the surgery. Typical procedures include endometrial ablation, submucosal fibroid resection, and endometrial polypectomy. Hysteroscopy has also been used to apply the Nd:YAG laser treatment to the inside of the uterus.[7] Methods of tissue removal now include electrocautery bipolar loop resection, and morcellation.[8]

Indications

Hysteroscopy is useful in a number of uterine conditions:

- Asherman's syndrome (i.e. intrauterine adhesions). Hysteroscopic adhesiolysis is the technique of lysing adhesions in the uterus using either microscissors (recommended) or thermal energy modalities. Hysteroscopy can be used in conjunction with laparascopy or other methods to reduce the risk of perforation during the procedure.[9]

- Endometrial polyp. Polypectomy.

- Abnormal uterine bleeding

- Adenomyosis

- Endometrial ablation[10] (Some newer systems specifically developed for endometrial ablation such as the Novasure do not require hysteroscopy)

- Myomectomy for uterine fibroids.[1]

- Congenital uterine malformations (also known as Mullerian malformations).[2][7]

- Evacuation of retained products of conception in selected cases.

- Removal of embedded IUDs.[11]

The use of hysteroscopy in endometrial cancer is not established as there is concern that cancer cells could be spread into the peritoneal cavity.[12]

Hysteroscopy has the benefit of allowing direct visualization of the uterus, thereby avoiding or reducing iatrogenic trauma to delicate reproductive tissue which may result in Asherman's syndrome.

Hysteroscopy allows access to the utero-tubal junction for entry into the Fallopian tube; this is useful for tubal occlusion procedures for sterilization and for falloposcopy.

Complications

A possible problem is uterine perforation when either the hysteroscope itself or one of its operative instruments breaches the wall of the uterus. This can lead to bleeding and damage to other organs. If other organs such as bowel are injured during a perforation, the resulting peritonitis can be fatal. Furthermore, cervical laceration, intrauterine infection (especially in prolonged procedures), electrical and laser injuries, and complications caused by the distention media can be encountered.

The use of insufflation (also called distending) media can lead to serious and even fatal complications due to embolism or fluid overload with electrolyte imbalances.[1][6] Particularly the electrolyte-free insufflation media increase the risk of fluid overload with electrolyte imbalances, particularly hyponatremia, heart failure as well as pulmonary and cerebral edema. The main factors contributing to fluid overload in hysteroscopy are:[13]

- Hydrostatic pressure of the insufflation media

- Amount of exposed blood vessels, such as being increased in endometrial ablation and myomectomy.

- Duration of the hysteroscopy procedure.

Women in fertile age are at increased risk of resultant hyponatremic encephalopathy, likely because of increased level of estrogens.[13]

The overall complication rate for diagnostic and operative hysteroscopy was 2% with serious complications occurring in less than 1% of cases using older methods.[1] Morcellation has fewer complications than electrocautery, less than 0.1%. [14][15]

Severe Pain

The English Member of Parliament, Lyn Brown (West Ham, Labour), has spoken twice in the House of Commons on behalf of constituents who have been coerced into completing unbearably painful outpatient hysteroscopies without anaesthesia. Lyn Brown cites numerous instances of women throughout England being held down by nurses in order to complete an ambulatory hysteroscopy and thus avoid the expense of safely monitored sedation or general anaesthetic.[16] A petition to grant NHS patients full information about the risks of severe outpatient hysteroscopy pain, and the upfront choice of local anaesthetic, sedation, epidural or general anaesthetic was launched in summer 2018. 'End barbaric NHS hysteroscopies with inadequate pain-relief'. It asks the Secretary of State for Health to ensure that:

1. All NHS hysteroscopists have advanced training in pain medicine.

2. All hysteroscopy patients receive full written information before the procedure, listing the risks and benefits and explaining that local anaesthetic may be painful and ineffective against the severe pain of cervical dilation, womb distension and biopsy.

3. All hysteroscopy services are adequately funded so that BEFORE their procedures patients may choose no anaesthesia/ local anaesthesia/ safely monitored conscious sedation/ epidural/ general anaesthetic.

4. The Best Practice Tariff financial incentive, which rewards NHS Trusts who perform a high percentage of hysteroscopies in outpatients without a trained anaesthetist, is abolished.

See also

- Essure procedure for sterilization

References

- Di Spiezio Sardo A, Mazzon I, Bramante S, Bettocchi S, Bifulco G, Guida M, Nappi C (2008). "Hysteroscopic myomectomy: a comprehensive review of surgical techniques". Hum Reprod Update. 14 (2): 101–19. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmm041. PMID 18063608.

- Nouri K, Ott J, Huber JC, Fischer EM, Stogbauer L, Tempfer CB (2010). "Reproductive outcome after hysteroscopic septoplasty in patients with septate uterus - a retrospective cohort study and systematic review of the literature". Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 8: 52. doi:10.1186/1477-7827-8-52. PMC 2885403. PMID 20492650.

- Agostini, A.; Collette, E.; Provansal, M.; Estrade, J. -P.; Blanc, B.; Gamerre, M. (2008). "Bonne pratique et valeur diagnostique de l'hystéroscopie diagnostique et des prélèvement histologiques". Journal de Gynécologie Obstétrique et Biologie de la Reproduction. 37 (8): S343–8. doi:10.1016/S0368-2315(08)74774-4. PMID 19268212.

- Laparoscopy and Hysteroscopy. A Guide for Patients, Revised 2012. From the American Society for Reproductive Medicine, Patient Education Committee

- Polyzos, N. P.; Zavos, A.; Valachis, A.; Dragamestianos, C.; Blockeel, C.; Stoop, D.; Papanikolaou, E. G.; Tournaye, H.; Devroey, P.; Messinis, I. E. (2012). "Misoprostol prior to hysteroscopy in premenopausal and post-menopausal women. A systematic review and meta-analysis". Human Reproduction Update. 18 (4): 393–404. doi:10.1093/humupd/dms014. PMID 22544173.

- Van Kruchten PM, Vermelis JM, Herold I, Van Zundert AA (2010). "Hypotonic and isotonic fluid overload as a complication of hysteroscopic procedures: two case reports". Minerva Anestesiol. 76 (5): 373–7. PMID 20395900.

- Yang J, Yin TL, Xu WM, Xia LB, Li AB, Hu J (2006). "Reproductive outcome of septate uterus after hysteroscopic treatment with neodymium:YAG laser". Photomed Laser Surg. 24 (5): 625. doi:10.1089/pho.2006.24.625. PMID 17069494.

- Smith, Paul P.; Middleton, Lee J.; Connor, Mary; Clark, T. Justin (April 2014). "Hysteroscopic Morcellation Compared With Electrical Resection of Endometrial Polyps". Obstetrics & Gynecology. 123 (4): 745–751. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000000187. PMID 24785600.

- Yu D, Wong YM, Cheong Y, Xia E, Li TC (2008). "Asherman syndrome--one century later". Fertil. Steril. 89 (4): 759–79. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.02.096. PMID 18406834.

- Papadopoulos NP, Magos A (2007). "First-generation endometrial ablation: roller-ball vs loop vs laser". Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 21 (6): 915–29. doi:10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2007.03.014. PMID 17459778.

- Siegler AM, Kemmann E (1976). "Location and removal of misplaced or embedded intrauterine devices by hysteroscopy". J Reprod Med. 16 (3): 139–44. PMID 943543.

- Polyzos NP, Mauri D, Tsioras S, Messini CI, Valachis A, Messinis IE (2010). "Intraperitoneal dissemination of endometrial cancer cells after hysteroscopy: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Int J Gynecol Cancer. 20 (2): 261–7. doi:10.1111/IGC.0b013e3181ca2290. PMID 20169669.

- Munro MG, Storz K, Abbott JA, et al. (2013). "AAGL Practice Report: Practice Guidelines for the Management of Hysteroscopic Distending Media: (Replaces Hysteroscopic Fluid Monitoring Guidelines. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2000;7:167-168.)" (PDF). J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 20 (2): 137–48. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2012.12.002. PMID 23465255.

- Haber, Karina; Hawkins, Eleanor; Levie, Mark; Chudnoff, Scott (January 2015). "Hysteroscopic Morcellation: Review of the Manufacturer and User Facility Device Experience (MAUDE) Database". Journal of Minimally Invasive Gynecology. 22 (1): 110–114. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2014.08.008. PMID 25128851.Epub 2014 Aug 14

- Noventa, M.; Ancona, E.; Quaranta, M.; Vitagliano, A.; Cosmi, E.; D'Antona, D.; Gizzo, S. (14 April 2015). "Intrauterine Morcellator Devices: The Icon of Hysteroscopic Future or Merely a Marketing Image? A Systematic Review Regarding Safety, Efficacy, Advantages, and Contraindications". Reproductive Sciences. 22 (10): 1289–1296. doi:10.1177/1933719115578929. PMID 25878200. Epub 2015 Apr 14

- Hansard : 19 December 2013; and • Hansard : 18 December 2014