Immortalised cell line

An immortalised cell line is a population of cells from a multicellular organism which would normally not proliferate indefinitely but, due to mutation, have evaded normal cellular senescence and instead can keep undergoing division. The cells can therefore be grown for prolonged periods in vitro. The mutations required for immortality can occur naturally or be intentionally induced for experimental purposes. Immortal cell lines are a very important tool for research into the biochemistry and cell biology of multicellular organisms. Immortalised cell lines have also found uses in biotechnology.

| Immortalised cell line | |

|---|---|

| |

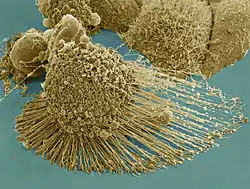

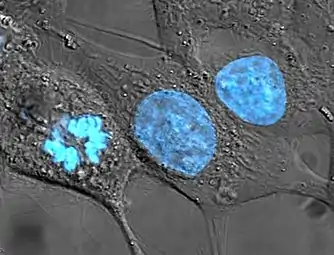

HeLa cells, an example of an immortalised cell line. DIC image, DNA stained with Hoechst 33258. | |

| Identifiers | |

| MeSH | D002460 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

An immortalised cell line should not be confused with stem cells, which can also divide indefinitely, but form a normal part of the development of a multicellular organism.

Relation to natural biology and pathology

There are various immortal cell lines. Some of them are normal cell lines (e.g. derived from stem cells). Other immortalised cell lines are the in vitro equivalent of cancerous cells. Cancer occurs when a somatic cell which normally cannot divide undergoes mutations which cause de-regulation of the normal cell cycle controls leading to uncontrolled proliferation. Immortalised cell lines have undergone similar mutations allowing a cell type which would normally not be able to divide to be proliferated in vitro. The origins of some immortal cell lines, for example HeLa human cells, are from naturally occurring cancers. HeLa, the first-ever immortal human cell line, was taken from Henrietta Lacks (without informed consent[1]) in 1951 at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, Maryland.

Role and uses

Immortalised cell lines are widely used as a simple model for more complex biological systems, for example for the analysis of the biochemistry and cell biology of mammalian (including human) cells.[2] The main advantage of using an immortal cell line for research is its immortality; the cells can be grown indefinitely in culture. This simplifies analysis of the biology of cells which may otherwise have a limited lifetime.

Immortalised cell lines can also be cloned giving rise to a clonal population which can, in turn, be propagated indefinitely. This allows an analysis to be repeated many times on genetically identical cells, which is desirable for repeatable scientific experiments. The alternative, performing an analysis on primary cells from multiple tissue donors, does not have this advantage.

Immortalised cell lines find use in biotechnology, where they are a cost-effective way of growing cells similar to those found in a multicellular organism in vitro. The cells are used for a wide variety of purposes, from testing toxicity of compounds or drugs to production of eukaryotic proteins.

Changes from nonimmortal origins

While immortalised cell lines often originate from a well-known tissue type, they have undergone significant mutations to become immortal. This can alter the biology of the cell and must be taken into consideration in any analysis. Further, cell lines can change genetically over multiple passages, leading to phenotypic differences among isolates and potentially different experimental results depending on when and with what strain isolate an experiment is conducted.[3]

Contamination with other cells

Many cell lines that are widely used for biomedical research have been contaminated and overgrown by other, more aggressive cells. For example, supposed thyroid lines were actually melanoma cells, supposed prostate tissue was actually bladder cancer, and supposed normal uterine cultures were actually breast cancer.[4]

Methods of generation

There are several methods for generating immortalised cell lines:[5]

- Isolation from a naturally occurring cancer. This is the original method for generating an immortalised cell line. Major examples include human HeLa cells that were obtained from a cervical cancer, mouse Raw 264.7 cells that were subjected to mutagenesis and then selected for cells which are able to undergo division.[6]

- Introduction of a viral gene that partially deregulates the cell cycle (e.g., the adenovirus type 5 E1 gene was used to immortalise the HEK 293 cell line; the Epstein-Barr virus can immortalise B lymphocytes by infection[7]).

- Artificial expression of key proteins required for immortality, for example telomerase which prevents degradation of chromosome ends during DNA replication in eukaryotes. [8]

- Hybridoma technology, specifically used for generating immortalised antibody-producing B cell lines, where an antibody-producing B cell is fused with a myeloma (B cell cancer) cell.[9]

Examples

There are several examples of immortalised cell lines, each with different properties. Most immortalised cell lines are classified by the cell type they originated from or are most similar to biologically.

- 3T3 cells – a mouse fibroblast cell line derived from a spontaneous mutation in cultured mouse embryo tissue.

- A549 cells – derived from a cancer patient lung tumor.

- HeLa cells – a widely used human cell line isolated from cervical cancer patient Henrietta Lacks.

- HEK 293 cells – derived from human fetal cells.

- Jurkat cells – a human T lymphocyte cell line isolated from a case of leukemia.

- OK cells – derived from female North American opossum kidney cells

- Ptk2 cells – derived from male long-nosed potoroo epithelial kidney cells.

- Vero cells – a monkey kidney cell line that arose by spontaneous immortalisation.

See also

References

- Skloot R (2010). Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, the. Random House. ISBN 978-0-307-71253-0. OCLC 974000732. Retrieved 2020-09-20.

- Kaur G, Dufour JM (January 2012). "Cell lines: Valuable tools or useless artifacts". Spermatogenesis. 2 (1): 1–5. doi:10.4161/spmg.19885. PMC 3341241. PMID 22553484.

- Marx V (April 2014). "Cell-line authentication demystified". Technology Feature. Nature Methods (Paper "Nature Reprint Collection, Technology Features" (Nov 2014)). 11 (5): 483–8. doi:10.1038/nmeth.2932. PMID 24781320. S2CID 205422738.

- Neimark J (February 2015). "Line of attack". Science. 347 (6225): 938–40. doi:10.1126/science.347.6225.938. PMID 25722392.

- Maqsood MI, Matin MM, Bahrami AR, Ghasroldasht MM (October 2013). "Immortality of cell lines: challenges and advantages of establishment". Cell Biology International. 37 (10): 1038–45. doi:10.1002/cbin.10137. PMID 23723166. S2CID 14777249.

- Kong L, Smith W, Hao D (May 2019). "Overview of RAW264.7 for osteoclastogensis study: Phenotype and stimuli". Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine. 23 (5): 3077–3087. doi:10.1111/jcmm.14277. PMC 6484317. PMID 30892789.

- Henle W, Henle G (1980). "Epidemiologic aspects of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-associated diseases". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 354: 326–31. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1980.tb27975.x. PMID 6261650.

- Bodnar AG, Ouellette M, Frolkis M, Holt SE, Chiu CP, Morin GB, et al. (January 1998). "Extension of life-span by introduction of telomerase into normal human cells". Science. 279 (5349): 349–52. doi:10.1126/science.279.5349.349. PMID 9454332.

- Kwakkenbos MJ, van Helden PM, Beaumont T, Spits H (March 2016). "Stable long-term cultures of self-renewing B cells and their applications". Immunological Reviews. 270 (1): 65–77. doi:10.1111/imr.12395. PMID 26864105.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cell lines. |

- ATCC – American Type Culture Collection

- Cellosaurus – a knowledge resource on cell lines

- CellBank Australia – Australia's national not-for-profit cell line repository