Indian people

Indians are the nationals and citizens of India, the second most populous nation in the world, containing 17.50% of the world's population. In India, the term "Indian" refers to nationality, rather than a particular ethnicity or language; the Indian nationality consists of dozens of regional ethno-linguistic groups, reflecting the rich and complex history of the country. Due to emigration, the Indian diaspora is present throughout the world, notably in other parts of Asia, North America, Europe, the Caribbean, Oceania, and Africa.[4] The demonym Indian applies to nationals of the present-day Republic of India, but also to people residing outside of India, who are called Overseas Indians.[26][27]

| |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| c. 1.21 billion[1][2] 2011 Census of India c. 1.34 billion[3] 2017 estimate c. 30.8 million[4] Population of Overseas Indians | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 4,100,000[5][6] | |

| 3,500,000[7] | |

| 3,456,477[8] | |

| 2,012,600[9] | |

| 2,000,000[7][10][11][12] | |

| 1,451,862[13] | |

| 1,374,710[14] | |

| 1,274,867[15] | |

| 1,030,000[16] | |

| 994,500[4] | |

| 839,504[17] | |

| 796,001[4] | |

| 700,000[18] | |

| 650,000[19] | |

| 600,000[20] | |

| 470,376[4] | |

| 468,800[21] | |

| 465,000[4] | |

| 400,000[4] | |

| 327,000[4] | |

| 315,000[4] | |

| 250,300[22] | |

| 197,301[4] | |

| 161,000[23] | |

| 156,000[4] | |

| 155,178[24] | |

| 148,000[4] | |

| 120,000[4] | |

| 109,000[4] | |

| 20,000+ [25] | |

| Languages | |

| Languages of India, including: | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly: Hinduism Minorities: | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Indian diaspora | |

In Canada, the Caribbean, and the United States, the terms Asian Indian and East Indian are sometimes used to avoid confusion with First Nations in Canada, the indigenous people of the Caribbean, and Native Americans in the U.S., which are also commonly known as "Indian".

Ethnonym

The name Bhārata has been used as a self-ascribed name by people of the Indian subcontinent and the Republic of India.[28] The designation "Bhārata" appears in the official Sanskrit name of the country, Bhārata Gaṇarājya. The name is derived from the ancient Vedic and Puranas, which refer to the land that comprises India as "Bhārata varṣam" and uses this term to distinguish it from other varṣas or continents.[29] The Bhāratas were a vedic tribe mentioned in the Rigveda, notably participating in the Battle of the Ten Kings.[30] India is named after legendary Emperor Bharata who was a descendant of the Bhāratas tribe, scion of Kuru Dynasty who unified the Indian Subcontinent under one realm.[31]

- उत्तरं यत्समुद्रस्य हिमाद्रेश्चैव दक्षिणम् ।

- वर्षं तद् भारतं नाम भारती यत्र संततिः ।।

- "The country (varṣam) that lies north of the ocean and south of the snowy mountains is called Bhāratam; there dwell the descendants of Bharata."[32][33]

In early Vedic literature, the term Āryāvarta (Sanskrit: आर्यावर्त) was in popular use before Bhārata. The Manusmṛti (2.22) gives the name Āryāvarta to "the tract between the Himalaya and the Vindhya ranges, from the Eastern (Bay of Bengal) to the Western Sea (Arabian Sea)".[34][35]

While the word Indian and India is derived from Greek Ἰνδία (Indía), via Latin India. Indía in Koine Greek denoted the region beyond the Indus (Ἰνδός) river, since Herodotus (5th century BC) ἡ Ἰνδική χώρη, hē Indikē chōrē; "the Indian land", Ἰνδός, Indos, "an Indian", from Old Persian Hinduš and medieval term Hindustani.[36] The name is derived ultimately from Sindhu, the Sanskrit name of the river Indus, but also meaning "river" generically.[37]

History

The history of India includes the prehistoric settlements and societies in the Indian subcontinent; the blending of the Indus Valley Civilization and Indo-Aryan culture into the Vedic Civilization; the development of Hinduism as a synthesis of various Indian cultures and traditions; the rise of sixteen oligarchic republics known as Mahajanapadas; the rise of the Śramaṇa movement; the birth of Jainism and Buddhism in the 6th-century BCE,[38] and the onset of a succession of powerful dynasties and empires for more than two millennia throughout various geographic areas of the subcontinent, including the growth of Muslim dynasties during the Medieval period intertwined with Hindu powers; the advent of European traders resulting in the establishment of the British rule; and the subsequent independence movement that led to the Partition of India and the creation of the Republic of India.

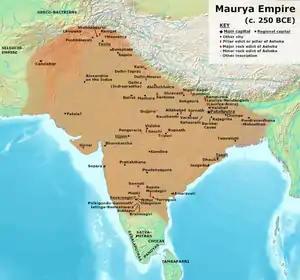

The Indian people established during ancient, medieval to early eighteenth century some of the greatest empires and dynasties in South Asian history like the Maurya Empire, Satavahana dynasty, Gupta Empire, Rashtrakuta dynasty, Chalukya Empire, Chola Empire, Karkota Empire, Pala Empire, Vijayanagara Empire, Maratha Empire and Sikh Empire. The first great Empire of the Indian people was the Maurya Empire having Patliputra(currently Patna, Bihar) as its capital, conquered the major part of South Asia in the 4th and 3rd century BC during the reign of the Indian Emperors Chandragupta Maurya and Ashoka alongside their senior advisor, Acharya Chanakya, the pioneer of the field of political science and economics in the World. The next great ancient Empire of the Indian people was the Gupta Empire. This period, witnessing a Hindu religious and intellectual resurgence, is known as the classical or "Golden Age of India". During this period, aspects of Indian civilisation, administration, culture, and Hinduism and Buddhism spread to much of Asia, while Chola Empire in the south had flourishing maritime trade links with the Roman Empire during this period. The ancient Indian mathematicians Aryabhata, Bhāskara I and Brahmagupta invented the concept of zero and the Hindu–Arabic numeral system decimal system during this period.[39] During this period Indian cultural influence spread over many parts of Southeast Asia which led to the establishment of Indianized kingdoms in Southeast Asia.[40]

During the early medieval period the great Rashtrakuta dynasty dominated the major part of the Indian subcontinent. from the 8th to 10th century and the Indian Emperor Amoghavarsha of the Rashtrakuta Dynasty was described by the Arab traveller Sulaiman as one of the four great kings of the world.[41] The medieval south Indian mathematician Mahāvīra lived in the Rashtrakuta dynasty and was the first Indian mathematician who separated astrology from mathematics and who wrote the earliest Indian text entirely devoted to mathematics.[42] The greatest maritime Empire of the medieval Indians was the Chola dynasty. Under the great Indian Emperors Rajaraja Chola I and his successor Rajendra Chola I the Chola dynasty became a military, economic and cultural power in South Asia and South-East Asia.[43][44] The power of the Chola empire was proclaimed to the eastern world by the expedition to the Ganges which Rajendra Chola I undertook and by the occupation of cities of the maritime empire of Srivijaya in Southeast Asia, as well as by the repeated embassies to China.[45]

During the late medieval period the great Vijayanagara Empire dominated the major part of southern India from the 14th to 16th century and reached its peak during the reign of the south Indian Emperor Sri Krishnadevaraya[46] The medieval Kerala School of Astronomy and Mathematics flourished during this period under such well known south Indian mathematicians as Madhava (c. 1340-1425) who made important contributions to Trigonometery and Calculus, and Nilakhanta (c. 1444-1545) who postulated on the orbitals of planets.[47]

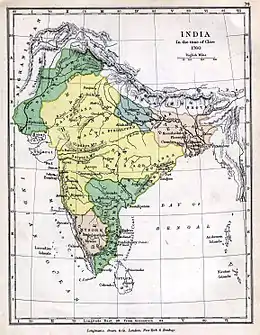

The Mughal Empire unified much of Indian sub-continent under one realm. Under the Mughals India developed a strong and stable economy, leading to commercial expansion and greater patronage of culture. This marked a huge influence in the Indian society.[48] The Mughal Empire balanced and pacified local societies through new administrative practices[49][50] and had diverse and inclusive ruling elites,[51] leading to more systematic, centralised, and uniform rule.[52] Newly coherent social groups in northern and western India, such as the Marathas, the Rajputs, the Pathans, the Jats and the Sikhs, gained military and governing ambitions during Mughal rule, which, through collaboration or adversity, gave them both recognition and military experience.[53][54][55][56]

The Marathas and Sikhs emerged in the 17th century and established the Maratha Empire and Sikh Empire which became the dominant power in India in the 18th century.[57] The Maratha Empire is credited to a large extent for ending the Mughal rule in India.[58][59][60][61] The empire at its peak stretched from Tamil Nadu in the south, to Peshawar, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa in the north[62] and Bengal and Andaman Islands in the east.[63]

The decline of Mughal Empire and Maratha Empire from the late 18th century to the mid-19th century lead to large areas of India annexed by the British East India Company of the British Empire and witnessed a period of rapid development of infrastructure, economic decline and major famines.[64][65] During the first half of the 20th century, a nationwide struggle for Indian independence movement was launched, the Indian subcontinent gained independence from the United Kingdom in 1947, after the British provinces were partitioned into the dominions of India and Pakistan and the princely states all acceded to one of the new states.[66][67][68]

Culture

India is one of the world's oldest civilisations.[69] The Indian culture, often labelled as an amalgamation of several various cultures, spans across the Indian subcontinent and has been influenced and shaped by a history that is several thousand years old.[70][71] Throughout the history of India, Indian culture has been heavily influenced by Dharmic religions.[72] They have been credited with shaping much of Indian philosophy, literature, architecture, art and music.[73] Greater India was the historical extent of Indian culture beyond the Indian subcontinent. This particularly concerns the spread of Hinduism, Buddhism, architecture, administration and writing system from India to other parts of Asia through the Silk Road by the travellers and maritime traders during the early centuries of the Common Era.[74][75] To the west, Greater India overlaps with Greater Persia in the Hindu Kush and Pamir Mountains.[76] During medieval period, Islam played a significant role in shaping Indian cultural heritage[77] Over the centuries, there has been significant integration of Hindus, Jains, and Sikhs with Muslims across India[78][79]

Religion

India is the birthplace of Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism and Sikhism, collectively known as Indian religions.[72] Indian religions, also known as Dharmic religions are a major form of world religions along with Abrahamic ones. Today, Hinduism and Buddhism are the world's third- and fourth-largest religions respectively, with over 1 billion followers altogether,[80][81][82] and possibly as many as 1.5 or 1.6 billion followers.[80][83] Throughout India's history, religion has been an important part of the country's culture. Religious diversity and religious tolerance are both established in the country by the law and by custom; the Constitution of India has declared the right to freedom of religion to be a fundamental right.[84]

Atheism and agnosticism have a long history in India and flourished within Śramaṇa movement.[85] The Cārvāka school originated in India around the 6th century BCE and is one of the earliest form of materialistic and atheistic movement in ancient India.[86][87][88] Sramana, Buddhism, Jainism, Ājīvika and some schools of Hinduism like Samkhya consider atheism to be valid and reject the concept of creator deity, ritualism and supernaturalism.[89][90][91] India has produced some notable atheist politicians and social reformers.[92][93]

Although 80% of the citizens of India are Hindus, the country has a substantial population of Muslims, Christians, Sikhs, Buddhists, Jains, Parsis and adherents of tribal faiths.[94] Zoroastrianism and Judaism each has several thousands of Indian adherents, and also have an ancient history in India.[95] India has the largest population of people adhering to Zoroastrianism and Baháʼí Faith in the world, even though these two religions are not native to India.[96] Many other world religions also have a relationship with Indian spirituality, such as the Baháʼí Faith which recognises Buddha and Krishna as manifestations of the God Almighty.[97] Despite the strong role of religion in Indian life, atheism and agnostics also have visible influence along with a self-ascribed tolerance to other people. According to the 2012 WIN-Gallup Global Index of Religion and Atheism report, 81% of Indians were religious, 13% were not religious, 3% were convinced atheists, and 3% were unsure or did not respond.[98]

Traditionally, Indian society is grouped according to their caste. It is a system in which social stratification within various social sections defined by thousands of endogamous hereditary groups are often termed jāti or castes. Within a jāti, there exists exogamous groups known as gotras, the lineage or clan of an individuals.[99] Caste barriers have mostly broken down in cities but still exists in some form in rural areas.[100]

Hinduism is the majority in most states; Kashmir and Lakshadweep are Muslim majority; Nagaland, Mizoram and Meghalaya are Christian majority; Punjab is a Sikh majority with Hindus 37%. Although participants in the Indian census may choose to not declare their religion, there is no mechanism for a person to indicate that he/she does not adhere to any religion. Due to this limitation in the Indian census process, the data for persons not affiliated with any religion may not be accurate. India contains the majority of the world's Hindus, Jains, Sikhs, Zoroastrians and Baháʼí. Christianity is widespread in the Northeast India, parts of southern India, particularly in Kerala and among various populations of Central India. Muslims are the largest religious minority. India is also home to the third-largest Muslim population in the world after Indonesia and Pakistan.[101][102][103]

Family

Historically, India had a prevailing tradition of the joint family system or undivided family. Joint family system is an extended family arrangement prevalent throughout the Indian subcontinent, particularly in India.[104] The family is headed by a patriarch, the oldest male, who makes decisions on economic and social matters on behalf of the entire family. The patriarch's wife generally exerts control over the household, minor religious practices and often wields considerable influence in domestic matters. A patrilineal joint family consists of an older man and his wife, his sons and unmarried daughters, his sons’ wives and children. Family income flows into a common pool, from which resources are drawn to meet the needs of all members, which are regulated by the heads of the family.[105] However, with modernisation and economic development, India has witnessed a break up of traditional joint family into more nuclear families and the traditional joint family in India accounted for a small percent of Indian households.[106][107]

Arranged marriages have been the tradition in Indian society. Marriage is considered a union of the two families rather than just the individuals, the process involved in an arranged marriage can be different depending on the communities and families. Recent survey study found that fewer marriages are purely arranged without consent and that the majority of surveyed Indian marriages are arranged with consent.[108] The study also suggested that Indian culture is trending away from traditional arranged marriages, they find that the marriage trends in India are similar to trends observed over last 40 years where arranged marriages was previously common, particularly in China and Japan.[108]

Dress

India's clothing styles have continuously evolved over the course of history. Cotton was first cultivated in Indian subcontinent around the 5th millennium BC.[109] Dyes used during this period are still in use, particularly indigo, red madder, lac and turmeric.[110] Silk was woven around 2450 BC and 2000 BC.[111][112] In 11th-century BC Rig-veda mentions dyed and embroidered garments known as paridhan and pesas respectively and thus highlights the development of sophisticated garment manufacturing techniques during this period.[113] In the 5th century BCE, Greek historian Herodotus describes the richness of the quality of Indian textiles.[114] By the 2nd century AD, cotton, muslins and silk textiles manufactured in India were imported by the Roman Empire and was one of the major exports of ancient India to other parts of the world along with Indian spices and Wootz steel.[115] Traditional Indian clothing greatly varies across different parts of the country and is influenced by local culture, geography and climate. Women traditionally wear Sari, Gagra Choli, Angarkha, Phiran, Shalwar Kameez, Gharara and Bandi with Dupatta or Ghoonghat worn over head or shoulder to complete the outfit.[116] Men traditionally wear Angarkha, Achkan, Kurta, Kameez, Phiran, Sherwani and Koti for upper garment, lower garment includes Dhoti, Churidar, Shalwar, and Lungi. Pagri is usually worn around head to complete the outfit.[117] In urban centres, people often wear western clothing and variety of other contemporary fashion.[118]

Cuisine

Indian food varies from region to region. Staple foods of Indian cuisine include a variety of lentils (dal), whole-wheat flour (aṭṭa), rice and pearl millet (bājra), which has been cultivated in Indian subcontinent since 6200 BCE.[119][120] Over time, segments of the population embraced vegetarianism during Śramaṇa movement[121][122] while an equitable climate permitted a variety of fruits, vegetables, and grains to be grown throughout the year. A food classification system that categorised any item as saatvic, raajsic or taamsic developed in Yoga tradition.[123][124] The Bhagavad Gita prescribed certain dietary practices. During this period, consumption of various types of meat became taboo, due to being considered sacred or impure.[125][126] Indian cuisines use numerous ingredients, deploy a wide range of food preparation styles, cooking techniques and culinary presentation depending on geographical location.[127]

Performing arts

The oldest preserved examples of Indian music are the melodies of the Samaveda (1000 BC) that are still sung in certain Śrauta sacrifices; this is the earliest account of Indian musical hymns.[128] The Samaveda, and other Hindu texts, heavily influenced India's classical music tradition, which is known today in two distinct styles: Hindustani music and Carnatic music. Both the Hindustani and Carnatic music systems are based on the melodic base known as Rāga, sung to a rhythmic cycle known as Tāla. These principles were refined in the nātyaśāstra (200 BC) and the dattilam (300 AD).[129]

The nātyaśāstrais an ancient Indian treatise on the performing arts, encompassing theatre, dance and music. It was written during the period between 200 BCE and 200 CE in classical India and is traditionally attributed to the Sage Bharata.[130] Natya Shastra is incredibly wide in its scope. While it primarily deals with stagecraft, it has come to influence music, classical dance, and literature as well. It covers stage design, music, dance, makeup, and virtually every other aspect of stagecraft.

Indian drama and theatre has a long history alongside its music and dance. One of the earliest known theatre play is Mṛcchakatika composed by Śudraka. Followed by Aśvaghoṣa's Śāriputraprakaraṇa and Bhāsa's Swapnavāsavadatta and Pancharātra. Most notable works are Kālidāsa's Abhijñānaśākuntala, Vikramorvaśīya and Mālavikāgnimitra. Harsha's Ratnavali, Priyadarsika, and Naganandam, other notable ancient dramatists include Bhatta Narayana, Bhavabhuti, Vishakhadatta, Thirayattam[131] and Viswanatha Kaviraja.[132]

Notable fable story-plays Panchatantra, Baital Pachisi, Kathasaritsagara, Brihatkatha and Jataka tales were performed in folk theatres since ancient period.[133] Jataka tales has become part of Southeast and East Asian folklore with the spread of Buddhism. These literature's were also influential in development of One Thousand and One Nights during medieval period.[134]

Contribution and discoveries

Indian people have played a major role in the development of the philosophy, sciences, mathematics, arts, architecture and astronomy throughout history. During the ancient period, notable mathematics accomplishment of India included Hindu–Arabic numeral system with decimal place-value and a symbol for zero, interpolation formula, Fibonacci's identity, theorem, the first complete arithmetic solution (including zero and negative solutions) to quadratic equations.[135] Chakravala method, sign convention, madhava series, and the sine and cosine in trigonometric functions can be traced to the jyā and koti-jyā.[136] Notable military inventions include war elephants, crucible steel weapons popularly known as Damascus steel and Mysorean rockets.[137] Other notable inventions during ancient period include chess, cotton, sugar, fired bricks, carbon pigment ink, ruler, lac, lacquer, stepwell, indigo dye, snake and ladder, muslin, ludo, calico, Wootz steel, incense clock, shampoo, palampore, chintz, and prefabricated homes.

Indian cultural aspects, religions, philosophy, arts and architecture have developed over several millennia and have spread through much of Asia in peaceful manner.[75] Many architectural structures of India such as Sanchi Stupa, Taj Mahal and Mahabodhi Temple are UNESCO World Heritage sites today.[138]

In modern times, Indian people have continued to contribute to mathematics, sciences and astrophysics. Among them are Satyendra Nath Bose, Srinivasa Ramanujan, Jagadish Chandra Bose, Meghnad Saha, Homi J. Bhabha, Prasanta Chandra Mahalanobis, and notable Nobel Prize recipients C. V. Raman, Har Gobind Khorana, Venkatraman Ramakrishnan, and Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar who is notable for currently accepted theory on the later evolutionary stages of massive stars, including black holes.[139]

National personification

Bharat Mata (Hindi, from Sanskrit भारत माता, Bhārata Mātā), Mother India, or Bhāratāmbā (from अंबा ambā 'mother') is the national personification of India as a mother goddess.

The image of Bharat Mata formed with the Indian independence movement of the late 19th century. A play by Kiran Chandra Bandyopadhyay, Bhārat Mātā, was first performed in 1873. She is usually depicted as a woman clad in an orange or saffron sari holding a flag, and sometimes accompanied by a lion.[140]

Indian diaspora

| Little India | |

|---|---|

People of Indian origin have achieved a high demographic profile in metropolitan areas worldwide, including India Square, in the heart of Bombay, Jersey City, New Jersey, US,[141] home to the highest concentration of Asian Indians in the Western Hemisphere[142] and one of at least 24 enclaves characterized as a Little India which have emerged within the New York City Metropolitan Area, with the largest metropolitan Indian population outside Asia, as large-scale immigration from India continues into New York.[143][144][145][146] |

Although, population groups originating in different parts of the Indian subcontinent and within the international borders of the modern country of India had been migrating to Southeast Asia, East Asia, Central Asia, North Africa, and even along the European mediterranean coast, the Indian diaspora generally socio-politically or historically refers to those whose families or themselves migrated to other parts of the world after the British Empire established itself in India. Population estimates vary from a conservative 12 million to 20 million diaspora.[147][148]

Britain

The British Indian community had grown to number over one million. According to the 2001 UK Census, 1,053,411 Britons had full Indian ancestry (representing 1.8% of the UK's population). An overwhelming majority of 99.3% resided in England (in 2008 the figure is thought to be around 97.0%). In the seven-year period between 2001 and 2009, the number of Indian-born people in the UK increased in size by 38% from 467,634 to around 647,000 (an increase of approximately 180,000).[149]

Canada

There are over 1.5 million people of Indian origin or ancestry in Canada, the majority of which live in Greater Toronto and Vancouver, with growing communities in Alberta and Quebec. Nearly 4% of the total Canadian population is of Indian ancestry, a figure higher than both the United States and Britain. According to Statistics Canada, Indo-Canadians are one of the fastest growing visible minority groups in Canada, making up the second largest group of non-European descent in the country after Chinese Canadians. The Indo-Canadian community can trace its history in Canada back 120 years to 1897 when a contingent of Sikh soldiers visited the western coast of Canada, primarily British Columbia which at the time was very sparsely populated and the Canadian government wanted to settle in order to prevent a takeover of the territory by the United States.

South Africa

More than a million people of Indian descent live in South Africa, concentrated around the city of Durban.

Tanzania

About 40,000 people of Indian origin live in Tanzania mostly in the urban areas.

United States

According to the American Community Survey of the United States Census Bureau, the Indian American population in the United States grew from almost 1.67 million in 2000 to 3.1 million in 2010 which is the third-largest Asian American community in the United States after Chinese Americans and Filipino Americans.

Caribbean

After slavery was abolished in the European colonies, Indian were hired to become indentured labourers to fill the need for cheap labor. Indians primarily from the Awadh and Bhojpur regions of the Hindi Belt in the present-day states of Bihar, Jharkhand, and Uttar Pradesh in North India and the Terai region in Nepal, along with a significant minority who came from South India, and a much extremely smaller minority who came from Bengal, Punjab, Braj, Bundelkhand, Bagelkhand, Mithila, Malwa, Jammu, Kashmir, Rohilkhand, Chhattisgarh, Odisha, Haryana, Maharashtra, Kutch, Marwar, Mewar, and Gujarat were sent to the Caribbean by the British, Dutch, and French from the late 1830s to the early 1920s as indentured laborers to work on the sugarcane, cocoa, rice, banana, and coffee estates. After the first wave of migration of indentured laborers, more Indians from Gujarat, Sindh, Kutch, Punjab, Bengal, and South India came to the Caribbean for business from the 1930s to present-day. There are more than a million Indo-Caribbeans. Most of them live in Trinidad and Tobago, Guyana, Suriname, and Jamaica. There are few in other Caribbean countries such as Martinique, Guadeloupe, French Guiana, Belize, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Saint Lucia, Barbados, Grenada, Saint Kitts and Nevis, and the British Virgin Islands. The Indians from Bhojpuri and Awadhi speaking areas of the Hindi Belt were the majority of Indians in Trinidad and Tobago, Guyana, Suriname, and Jamaica, hence their dialect of Hindustani became known as Caribbean Hindustani and it became the lingua franca of the Indian immigrants. Since the Bhojpuri and Awadhi speaking Indians formed the largest group of Indians, the traditions and culture from the Bhojpur, Purvaanchal, and Awadh regions became the dominant culture for the Indian in those countries. France had sent Indians from Southern India to their colonies in the Caribbean as indentured laborers, hence there are also many people of Indian descent living in Guadeloupe, Martinique, and French Guiana, most who are of South Indian descent. Many Indo-Caribbeans have migrated to the United States, United Kingdom, Canada, the Netherlands, and France, and few of them have even seasonally migrated to the neighboring Latin American and other Caribbean countries as migrant workers. A majority of Indo-Caribbean are Hindus, while there is significant minority of Muslims and Christians, along with smaller numbers of Jains, Sikhs, Buddhist, Baháʼís, or adherents of another faith. Indo-Caribbeans are known as the descendants of the jahajis or girmityas.[150][151][152][153][154]

Genetics

Recent genome studies appear to show that South Asians are mixture of two major ancestral components, one component restricted to South Asia and the other component shared with Central Asia, West Asia, and Europe.[155][156]

References

- "Population Enumeration Data (Final Population)". Census of India. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- "A – 2 DECADAL VARIATION IN POPULATION SINCE 1901" (PDF). Census of India. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- "Total Population - Both Sexes". World Population Prospects, the 2017 Revision. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, Population Estimates and Projections Section. June 2017. Archived from the original on 30 July 2017. Retrieved 22 June 2017.

- "Population of Overseas Indians" (PDF). Ministry of External Affairs (India). 31 December 2016. Retrieved 28 May 2016.

- "How Saudi Arabia's 'Family Tax' Is Forcing Indians To Return Home". The Huffington Post. 21 June 2017. Retrieved 21 June 2017.

- "Indians brace for Saudi 'family tax'". Times of India. Retrieved 21 June 2017.

- "India is a top source and destination for world's migrants". Pew Research Center. 3 March 2017. Retrieved 7 March 2017.

- "ASIAN ALONE OR IN ANY COMBINATION BY SELECTED GROUPS: 2016". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 14 February 2020. Retrieved 15 October 2016.

- "Population by States and Ethnic Group". Department of Information, Ministry of Communications and Multimedia, Malaysia. 2015. Archived from the original on 12 February 2016.

- Bagri, Neha Thirani. "There are more Indian migrants living in Pakistan than the United States". Quartz. Retrieved 7 March 2017.

- "More Indian migrants in Pakistan than in US: Pew report - Times of India". The Times of India. Retrieved 7 March 2017.

- "More Indian migrants living in Pakistan than US: PEW Research Centre - The Express Tribune". The Express Tribune. 7 March 2017. Retrieved 7 March 2017.

- "2011 Census: Ethnic group, local authorities in the United Kingdom". Office for National Statistics. 11 October 2013. Retrieved 28 February 2015.

- "Immigration and Ethnocultural Diversity Highlight Tables". statcan.gc.ca. 10 June 2016. Retrieved 2 May 2016.

- "Statistical Release P0302: Mid-year population estimates, 2011" (PDF). Statistics South Africa. 27 July 2011. p. 3. Retrieved 1 August 2011.

- The Indian Community in Myanmar. Archived from the original on 12 June 2010.

- "Sri Lanka Census of Population and Housing, 2011 – Population by Ethnicity" (PDF). Department of Census and Statistics, Sri Lanka. 20 April 2012.

- "Kuwait MP seeks five-year cap on expat workers' stay". Gulf News. 30 January 2014.

- "Population of Qatar by nationality - 2017 report". Retrieved 7 February 2017.

- "About India-Nepal Relations". Embassy of India, Kathmandu, Nepal. February 2020.

- "Overseas born Aussies highest in over a century". Australian Bureau of Statistics. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved 31 March 2016.

- "Population in Brief 2015" (PDF). Singapore Government. September 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 February 2016. Retrieved 14 February 2016.

- Immigration from outside Europe almost doubled Archived 9 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Federal Institute for Population Research. Retrieved 1 March 2017

- "[Stats NZ". stats.govt.nz. Retrieved 11 December 2017.

- "Indian Community In Ireland". irelandindiacouncil.ie. Ireland India Council. Archived from the original on 20 January 2018.

- Stern, Robert W. (2001). Democracy and Dictatorship in South Asia: Dominant Classes and Political Outcomes in India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 6. ISBN 9780275970413.

- Henry Newman (1921). The Calcutta Review. University of Calcutta. p. 252.

I have also found that Bombay is India, Satara is India, Bangalore is India, Madras is India, Delhi, Lahore, the Khyber, Lucknow, Calcutta, Cuttack, Shillong, etc., are all India.

- Article 1 of the English version of the Constitution of India: "India that is Bharat shall be a Union of States."

- Pargiter, F. F. (1922), Ancient Indian Historical Tradition, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, p. 131

- Schmidt, H.P. Notes on Rgveda 7.18.5-10. Indica. Organ of the Heras Institute, Bombay. Vol.17, 1980, 41-47.

- National Council of Educational Research and Training, History Text Book, Part 1, India

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 9 June 2007. Retrieved 10 April 2008.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Reading the Vedic Literature in Sanskrit" (PDF). is1.mum.edu. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 11 December 2017.

- Gopal, Madan (1990). K.S. Gautam (ed.). India through the ages. Publication Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India. p. 70.

- Michael Cook (2014), Ancient Religions, Modern Politics: The Islamic Case in Comparative Perspective, Princeton University Press, p.68: "Aryavarta [...] is defined by Manu as extending from the Himalayas in the north to the Vindhyas of Central India in the south and from the sea in the west to the sea in the east."

- Hudson, John C., ed., Goode's World Atlas 20th Edition Chicago, Illinois, USA:2000—Rand McNally Map Page 203 Major Languages of India—map of the ethnolinguistic groups of India

- Cheung, Martha Pui Yiu (2014) [2006]. "Zan Ning (919–1001 CE), To Translate Means to Exchange". An Anthology of Chinese Discourse on Translation: From Earliest Times to the Buddhist Project. Routledge. pp. 179, 181. ISBN 978-1-317-63928-2.

- "Religion -- Chapter 3". www.brow.on.ca. Retrieved 11 December 2017.

- The Earth and Its Peoples by Richard Bulliet, Pamela Crossley, Daniel Headrick, Steven Hirsch, Lyman Johnson p.192

- The Cambridge History of Southeast Asia: From early times to c. 1800, Band 1 by Nicholas Tarling p.281

- The Shaping of Modern Gujarat: Plurality, Hindutva, and Beyond; Acyuta Yājñika, Suchitra Sheth, Penguins Books, (2005), p.42, ISBN 978-0-14400-038-8

- The Math Book: From Pythagoras to the 57th Dimension, 250 Milestones by Clifford A. Pickover: page 88

- Kulke and Rothermund, p 115

- Keay, p 215

- K.A. Nilakanta Sastri, A History of South India, p 158

- Columbia Chronologies of Asian History and Culture by John Stewart Bowman p.270

- "History of Science and Philosophy of Science: A Historical Perspective of the Evolution of Ideas in Science", editor: Pradip Kumar Sengupta, author: Subhash Kak, 2010, p91, vol XIII, part 6, Publisher: Pearson Longman, ISBN 978-81-317-1930-5

- Zahir ud-Din Mohammad (10 September 2002). Thackston, Wheeler M. (ed.). The Baburnama: Memoirs of Babur, Prince and Emperor. New York: Modern Library. p. xlvi. ISBN 978-0-375-76137-9.

In India the dynasty always called itself Gurkani, after Temür's title Gurkân, the Persianized form of the Mongolian kürägän, 'son-in-law,' a title he assumed after his marriage to a Genghisid princess.

- Asher & Talbot 2008, p. 115.

- Robb 2001, pp. 90–91.

- Metcalf & Metcalf 2006, p. 17.

- Asher & Talbot 2008, p. 152.

- Catherine Ella Blanshard Asher; Cynthia Talbot (2006). India before Europe. Cambridge University Press. p. 265. ISBN 978-0-521-80904-7.

- Burjor Avari (2013). Islamic Civilization in South Asia: A History of Muslim Power and Presence in the Indian Subcontinent. Routledge. pp. 131–. ISBN 9780415580618.

- Erinn Banting (2003). Afghanistan: The people. ISBN 9780778793366.

- Metcalf & Metcalf 2006, pp. 23–24.

- Western India in the Nineteenth Century: A Study in the Social History by Ravinder Kumar p.5

- Pearson, M. N. (February 1976). "Shivaji and the Decline of the Mughal Empire". The Journal of Asian Studies. 35 (2): 221–235. doi:10.2307/2053980. JSTOR 2053980.

- Capper, John (11 December 2017). Delhi, the Capital of India. Asian Educational Services. ISBN 9788120612822. Retrieved 11 December 2017 – via Google Books.

- Sailendra Nath Sen (2010). An Advanced History of Modern India. p. Introduction-14. ISBN 9780230328853. Retrieved 15 December 2017.

The author says: "The victory at Bhopal in 1738 established Maratha dominance at the Mughal court"

- "Is the Pakistan army martial? - The Express Tribune". tribune.com.pk. 29 September 2012. Retrieved 11 December 2017.

- Sen, Sailendra Nath (11 December 2017). An Advanced History of Modern India. Macmillan India. ISBN 9780230328853. Retrieved 11 December 2017 – via Google Books.

- Andaman & Nicobar Origin | Andaman & Nicobar Island History Archived 15 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Andamanonline.in.

- Robb 2001, pp. 151–152.

- Metcalf, B.; Metcalf, T.R. (2006), A Concise History of Modern India (2nd ed.), pp. 94–99.

- Minahan, James (2012). Ethnic Groups of South Asia and the Pacific: An Encyclopedia: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 139. ISBN 978-1-59884-660-7.

- "Indian Economy During British Rule". yourarticlelibrary.com. 8 May 2014. Retrieved 6 January 2017.

- Ali, Afsar (17 July 2017). "Partition of India and Patriotism of Indian Muslims". The Milli Gazette.

- Kenoyer, Jonathan Mark; Heuston, Kimberley (May 2005). The Ancient South Asian World. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-517422-9. OCLC 56413341. Archived from the original on 20 November 2012.

- John Keay (2011), India: A History, 2nd Ed - Revised and Updated, Grove Press / Harper Collins, ISBN 978-0-8021-4558-1, see Introduction and Chapters 3 through 11

- Mohammada, Malika (2007), The foundations of the composite culture in India, Aakar Books, ISBN 81-89833-18-9

- Nikki Stafford Finding Lost, ECW Press, 2006 ISBN 1-55022-743-2 p. 174

- "1". Cultural History of India. New Age International Limited Publications. 2005. p. 3. ISBN 978-81-224-1587-2.

- Southeast Asia: A Historical Encyclopedia, from Angkor Wat to East Timor, by Keat Gin Ooi p.642

- Hindu-Buddhist Architecture in Southeast Asia by Daigorō Chihara p.226

- Lange, Christian (10 July 2008). Justice, Punishment and the Medieval Muslim Imagination. Cambridge Studies in Islamic Civilization. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-88782-3. Lange: Greater Persia (including Khwārazm, Transoxania, and Afghanistan)."

- Sharma, Usha (2004). Cultural and Religious Heritage of India. Mittal Publications, 2004. ISBN 978-81-7099-960-7.

- E. Dunn, Ross (1986). The adventures of Ibn Battuta, a Muslim traveller of the fourteenth century. University of California Press, 1986. ISBN 978-0-520-05771-5.

- Tharoor, Shashi (2006). India: From Midnight to the Millennium and Beyond. Arcade Publishing, 2006. ISBN 978-1-55970-803-6.

- "45". What Is Hinduism?: Modern Adventures Into a Profound Global Faith. Himalayan Academy Publications. 2007. p. 359. ISBN 978-1-934145-00-5.

- "Non Resident Nepali – Speeches". Nrn.org.np. Archived from the original on 25 December 2010. Retrieved 1 August 2010.

- "BBCVietnamese.com". Bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 1 August 2010.

- "Religions of the world: numbers of adherents; growth rates". Religioustolerance.org. Retrieved 1 August 2010.

- Basu, Durga Das (2013). Introduction to the Constitution of India (21 ed.). LexisNexis. p. 124. ISBN 978-81-803-8918-4.

- Johannes Quack (2014), Disenchanting India: Organized Rationalism and Criticism of Religion in India, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0199812615, page 50 with footnote 3.

- Ramkrishna Bhattacharya (2011), Studies on the Cārvāka/Lokāyata, Anthem Press, ISBN 978-0857284334, pages 26-29

- KN Tiwari (1998), Classical Indian Ethical Thought, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120816077, page 67;

Roy W Perrett (1984), The problem of induction in Indian philosophy, Philosophy East and West, 34(2): 161-174;

(Bhattacharya 2011, pp. 21–32);

(Radhakrishnan 1957, pp. 187, 227–234);

Robert Flint, Anti-theistic theories, p. 463, at Google Books, Appendix Note VII - Hindu Materialism: The Charvaka System; William Blackwood, London; - V.V. Raman (2012), Hinduism and Science: Some Reflections, Zygon - Journal of Religion and Science, 47(3): 549–574, Quote (page 557): "Aside from nontheistic schools like the Samkhya, there have also been explicitly atheistic schools in the Hindu tradition. One virulently anti-supernatural system is/was the so-called Charvaka school.", doi:10.1111/j.1467-9744.2012.01274.x

- Chakravarti, Sitansu (1991). Hinduism, a way of life. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. p. 71. ISBN 978-81-208-0899-7. Retrieved 9 April 2011.

- Joshi, L.R. (1966). "A New Interpretation of Indian Atheism". Philosophy East and West. 16 (3/4): 189–206. doi:10.2307/1397540. JSTOR 1397540.

- Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan; Charles A. Moore (1957). A Sourcebook in Indian Philosophy (Twelfth Princeton Paperback printing 1989 ed.). Princeton University Press. pp. 227–249. ISBN 978-0-691-01958-1.

- Phil Zuckerman (21 December 2009). "Chapeter 7: Atheism and Secularity in India". Atheism and Secularity. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0-313-35182-2. Retrieved 7 September 2013.

- Oxford Dictionary of World Religions, p. 259

- "Census of India – Socio-cultural aspects". Censusindia.gov.in. Retrieved 3 February 2011.

- Hodivala 1920, p. 88

- Smith, Peter (2008). An introduction to the Baha'i faith. Cambridge University Press. p. 94. ISBN 978-0-521-86251-6.

- Enroth, Ronald (2005). A Guide to New Religious Movements. InterVarsity Press. p. 160. ISBN 978-0-8308-2381-9.

- "Global Index Of Religion And Atheism" (PDF). WIN-Gallup. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 October 2012. Retrieved 3 September 2013.

- Singh, David Emmanuel (2012). Islamization in Modern South Asia: Deobandi Reform and the Gujjar Response. Walter de Gruyter. p. 199. ISBN 978-1-61451-246-2.

- Cassan, Guilhem (September 2011). "The Impact of Positive Discrimination in Education in India: Evidence from a Natural Experiment" (PDF). Paris School of Economics and Laboratoire d'Economie Appliquee.

- Indian and Foreign Review. 1965. Retrieved 6 May 2015.

- "UNITED STATES COMMISSION ON INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM-Annual Report 2015" (PDF).

- "15th anniversary retrospective:UNITED STATES COMMISSION ON INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM" (PDF).

- Talwar, Swati. "Meaning of HUF (Hindu Undivided Family)". Taxpaisa.com. Retrieved 29 June 2014.

- Henry Orenstein; Michael Micklin (1966). "The Hindu Joint Family: The Norms and the Numbers". Pacific Affairs. 39 (3/4): 314–325. doi:10.2307/2754275. JSTOR 2754275.

Autumn, 1966

- Raghuvir Sinha (1993). Dynamics of Change in the Modern Hindu Family. South Asia Books. ISBN 978-81-7022-448-8.

- "Indian Families". Facts About India. Archived from the original on 30 July 2011. Retrieved 11 October 2011.

- Manjistha Banerji; Steven Martin; Sonalde Desai (2008). "Is Education Associated with a Transition towards Autonomy in Partner Choice? A Case Study of India" (PDF). University of Maryland & NCAER. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2016.

- Stein, Burton (1998). A History of India. Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 0-631-20546-2, p. 47

- "Harrapa clothing". A.harappa.com. Retrieved 15 December 2017.

- Abbott, Phill (17 February 2009). "Rethinking silk's origins : Nature News". Nature. Nature.com. 457 (7232): 945. doi:10.1038/457945a. PMID 19238684. S2CID 4390646. Retrieved 9 November 2013.

- Good, I.L.; Kenoyer, J.M.; Meadow, R.H. (2009). "New evidence for early silk in the Indus civilization". Archaeometry. 50 (3): 457–466. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4754.2008.00454.x.

- Verma, S.P. (2005). Ancient system of oriental medicine. Anmol Publications PVT. LTD. ISBN 978-81-261-2127-4.

- Beveridge, Henry (1867). A comprehensive history of India. Blackie and son. ISBN 978-81-85418-45-2.

- Jayapalan, N. (2008). Economic History of India. Atlantic Publishers & Distributors. ISBN 978-81-269-0697-0.

- Govind Sadashiv Ghurye (1951) "Indian Costume.", p.11

- Govind Sadashiv Ghurye (1951) "Indian Costume.", p.12

- arti sandhu (2015). Indian Fashion: Tradition, Innovation, Style. bloomsbury. p. 126. ISBN 978-18478-8780-1. Retrieved 4 June 2012.

- K T Achaya (2003). The Story of Our Food. Universities Press. ISBN 9788173712937. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- Harris, David R. (1996). The Origins and Spread of Agriculture and Pastoralism in Eurasia. Psychology Press. p. 565. ISBN 978-1-85728-538-3.

- Padmanabh S Jaini (2001), Collected papers on Buddhist Studies, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120817760, pages 57-77

- Padmanabh S Jaini (2000), Collected papers on Jaina Studies, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120816916, pages 3-14

- Autobiography Of A Yogi, Paramahansa Yogananda, Self Realization Fellowship, 1973, p. 22

- Maharishi Mahesh Yogi on the Bhagavad Gita Translation and Commentary, Arkana, 1990 p. 236

- "Chapter 17, Verse 8,9,10". Bhagavad-Gita. Retrieved 31 August 2011.

- Donald K. Sharpes (2006). Sacred Bull, Holy Cow: A Cultural Study of Civilization's Most Important Animal. Peter Lang. p. 208. ISBN 978-0-8204-7902-6. Retrieved 4 June 2012.

- Harold McGee (2004). On food and cooking. Scribner. ISBN 978-0-684-80001-1.

- Emmie te Nijenhuis (1974). Indian music, Part 2, Volume 6. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-03978-0.

- A Study of Dattilam: A Treatise on the Sacred Music of Ancient India, 1978, p. 283, Mukunda Lāṭha, Dattila

- "Natyashastra" (PDF). Sanskrit Documents.

- "Thirayattam" (Folklore Text- malayalam, Moorkkanad apeethambaran), State Institute of language, Kerala. ISBN 978-81-200-4294-0

- Māni Mādhava Chākyār (1996). Nātyakalpadrumam. Sangeet Natak Akademi, New Delhi. p. 6.

- Burton, Richard F. (2002). Vikram and the Vampire Or Tales of Hindu Devilry pg xi. Adamant Media Corporation

- Irwin, Robert (2003), The Arabian Nights: A Companion, Tauris Parke Paperbacks, p. 65, ISBN 978-1-86064-983-7

- "History of Algebra". Retrieved 5 October 2014.

- Boyer, Carl B. (1991). A History of Mathematics (Second ed.). John Wiley & Sons, Inc.. ISBN 0-471-54397-7, p. 210.

- Narasimha Roddam (2 April 1985) Rockets in Mysore and Britain, 1750–1850 A.D., National Aeronautical Laboratory and Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore 560017 India, Project Document DU 8503,"Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2012. Retrieved 19 December 2011.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Properties Inscribed on the World heritage List". UNESCO. Retrieved 1 October 2010.

- "Nobel Prizes-Britannica". Retrieved 6 May 2015.

- "Life and Times of Bharat Mata - Manushi, Issue 142". indiatogether.org. Retrieved 11 December 2017.

- Kiniry, Laura. "Moon Handbooks New Jersey", Avalon Travel Publishing, 2006. pg. 34 ISBN 1-56691-949-5

- Laryssa Wirstiuk (21 April 2014). "Neighborhood Spotlight: Journal Square". Jersey City Independent. Archived from the original on 30 June 2018. Retrieved 26 December 2014.

- "Yearbook of Immigration Statistics: 2013 Supplemental Table 2". U.S. Department of Homeland Security. Retrieved 11 May 2015.

- "Yearbook of Immigration Statistics: 2012 Supplemental Table 2". U.S. Department of Homeland Security. Archived from the original on 22 December 2014. Retrieved 11 May 2015.

- "Yearbook of Immigration Statistics: 2011 Supplemental Table 2". U.S. Department of Homeland Security. Retrieved 11 May 2015.

- "Yearbook of Immigration Statistics: 2010 Supplemental Table 2". Department of Homeland Security. Retrieved 11 May 2015.

- "Executive Summary - The Indian Diaspora" (PDF). Indiandiaspora.nic.in. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 15 December 2017.

- "India and its Diaspora". Moia.gov.in. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016.

- "Estimated population resident in the United Kingdom, by foreign country of birth (Table 1.3)". Office for National Statistics. September 2009. Archived from the original on 22 January 2011. Retrieved 8 July 2010.

- "Forced Labour". The National Archives, Government of the United Kingdom. 2010.

- Hugh Tinker (1993). New System of Slavery. Hansib Publishing, London. ISBN 978-1-870518-18-5.

- K Laurence (1994). A Question of Labour: Indentured Immigration Into Trinidad & British Guiana, 1875-1917. St Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-312-12172-3.

- "St. Lucia's Indian Arrival Day". Caribbean Repeating Islands. 2009.

- "Indian indentured labourers". The National Archives, Government of the United Kingdom. 2010.

- Metspalu, Mait; et al. (2011). "Shared and Unique Components of Human Population Structure and Genome-Wide Signals of Positive Selection in South Asia". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 89 (6): 731–44. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.11.010. PMC 3234374. PMID 22152676.

- Moorjani, Priya; et al. (2013). "Genetic Evidence for Recent Population Mixture in India". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 93 (3): 422–438. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.07.006. PMC 3769933. PMID 23932107.