Indian club

Indian clubs, which originated in the Indian subcontinent,[1][2] are a type of exercise equipment used to present resistance in movement to develop strength and mobility. They consist of bowling-pin shaped wooden clubs of varying sizes and weights, which are swung in certain patterns as part of a strength exercise program. They can range in weight from a few pounds each to special clubs that can weigh as much as up to 100 pounds. They were used in carefully choreographed routines in which the clubs were swung in unison by a group of exercisers, led by an instructor, similar to 21st-century aerobics or zumba classes. The routines would vary according to the group's ability along with the weights of the clubs being used. When the 19th-century British colonists came across exercising clubs in India, they named them Indian clubs.

History

Club swinging is believed to have originated in India by soldiers as a method of improving strength, agility, balance and physical ability.[3]

Gada club is a blunt mace from the Indian subcontinent. Made either of wood or metal, it consists essentially of a spherical head mounted on a shaft, with a spike on the top. The gada is one of the traditional pieces of training equipment in Hindu physical culture, and is common in the akhara of north India. Maces of various weights and heights are used depending on the strength and skill level of the practitioner. It is believed that Lord Hanuman's gada was the largest amongst all the gadas in the world. For training purposes, one or two wooden gada (mudgar)[4][5] are swung behind the back in several different ways; this is particularly useful for building grip strength and shoulder endurance. Mudgar are mentioned in the Indian treatise Arthashastra written by Kautilya dated to 4th century BC.[6]

Several mauryan era coins depict club swinging; the Gupta era gold coin also depicts one of its kings performing club swinging with Gada. Gandharan fifth century schist used as wrestler's weight with Gada carved on it indicates that Gada might have been used as a training tool.[7] Manasollasa written in the twelfth century explicitly describes training exercises and club swinging along with wrestling. The thirteenth century text, Malla Purana, discusses Lord Krishna and Balarama’s prescriptions regarding wrestlers’ bodies and training methods such as club swinging; the text exhibits that the club swinging has long been a regulated practice. A Rajput painting from 1610 AD shows athletes performing various acrobatics including club swinging while dancing on Raga Desahka.[8] A Mughal painting from 1670 depicts Indian athletes using Indian clubs and performing other exercises such as weightlifting, mallakhamb.[9] In the nineteenth century when the British adopted Indian clubs they were remodelled into lightweight clubs bearing little resemblance to their traditional counterparts. Whereas traditional clubs weighed up to seventy pounds, those recommended, and adopted by Britain’s army, weighed four.[1]

While torches and other stick-like objects have been used in juggling for centuries, the modern juggling club was inspired by Indian clubs, which were first repurposed for juggling by DeWitt Cook in the 1800s.

Exceptionally popular during the fitness movement of the late Victorian era, used by military cadets and well-heeled ladies alike, they appeared as a gymnastic event in the 1904 and 1932 Olympics. Gymnasiums were built solely to cater to club exercise groups. During the late 19th and early 20th centuries they became increasingly common in Europe, the British Commonwealth and the United States.

Circa 1913/14 the Bodyguard unit of the British suffragette movement carried Indian clubs as concealed weapons for use against the truncheons of the police.[10]

The popularity of Indian clubs waned in Europe during the 1920s and 1930s as organized sports became more prevalent. Regimented exercise routines, like those requiring Indian clubs, were relegated to professional athletes and the military, who had access to more effective and modern strength training equipment.

There are physical fitness enthusiasts reviving the usage of Indian Clubs in the early 21st century, citing the aerobic exercise and safety advantages over traditional free weight regimens. There are nostalgic replicas of the original clubs being manufactured, as well as modern engineering updates to the concept, such as the Clubbell.[11][12]

Persian clubs

Exercise clubs similar to indian clubs are also found in Persia, where they are referred to as meels or mils (Persian: میل, romanized: mil).[13][14] The earliest records of this type of resistance device being used by wrestlers predates the 19th century, in ancient Persia, Egypt and the rest of the Middle East. Their practice has continued to the present day, notably in the varzesh-e bastani tradition practiced in the zurkaneh of Iran.

Gallery

Indian (British Raj) club swinging team, 1890s.

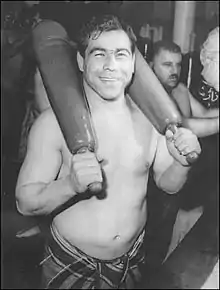

Indian (British Raj) club swinging team, 1890s. An Indian pehlwan (wrestler) training with clubs c. 1973.

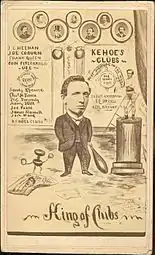

An Indian pehlwan (wrestler) training with clubs c. 1973. Carte de visite of Sim D. Kehoe, who brought Indian clubs to the United States from England.

Carte de visite of Sim D. Kehoe, who brought Indian clubs to the United States from England._-_Yazd_-_Central_Iran.jpg.webp) Men working out at Zurkhaneh (House of Strength) in Iran.

Men working out at Zurkhaneh (House of Strength) in Iran.

See also

References

- Heffernan, Conor (2016-07-05). Indian club swinging in nineteenth and twentieth-century India and England (Thesis thesis). Faculty of History, University of Cambridge.

- Heffernan, Conor (2017). "Indian club swinging in the early Victorian period". Sport in History. 37: 95–120. doi:10.1080/17460263.2016.1250807. S2CID 151888143.

- "The Therapeutic Benefits of Indian Club Swinging". www.dynamicchiropractic.com. 2011-10-07. Retrieved 2019-02-01.

- Kasulis, Thomas P.; Aimes, Roger T.; Dissanayake, Wimal (1993). Self as Body in Asian Theory and Practice. SUNY Press. ISBN 9780791410806.

- "exercise-club". British Museum. Retrieved 2019-02-01.

- "Arthasastra_English_Translation : R Shamasastry : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming". Internet Archive. p. 70. Retrieved 2020-08-22.

- Di Castro, Angelo Andrea (2003). "A Late Gandharan Wrestlers' Weight". East and West. 53 (1/4): 257–265. JSTOR 29757580.

- "painting". British Museum. Retrieved 2019-02-15.

- "Wrestlers exercising, illustrating the musical mode Deshakh Ragini".

- 1858–1928, Pankhurst, Emmeline (2015-09-24). My own story. London. ISBN 978-1784871253. OCLC 925307642.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- "Clubbell training". Stumptuous.COM. 18 July 2008.

- English, Nick (15 November 2016). "The Surprising Benefits of Club Training for Strength - BarBend". BarBend. Retrieved 2 April 2017.

- "Muscular Shias return to roots". BBC News. 22 April 2004. Retrieved 2018-02-07.

- Specimens of the Popular Poetry of Persia: As Found in the Adventures and Improvisations of Kurroglou, the Bandit-minstrel of Northern Persia and in the Songs of the People Inhabiting the Shores of the Caspian Sea. Oriental Translation Fund of Great Britain and Ireland. 1842. p. 457.

- Club History