Inkstick

Inksticks (Chinese: 墨 ![]() Mò; Japanese: 墨; Sumi; Korean: 먹 Meok) or Ink Cakes are a type of solid ink (India ink) used traditionally in several East Asian cultures for calligraphy and brush painting. Inksticks are made mainly of soot and animal glue, sometimes with incense or medicinal scents added. To make ink, the inkstick is ground against an inkstone with a small quantity of water to produce a dark liquid which is then applied with an ink brush. Artists and calligraphers may vary the concentration of the resulting ink according to their preferences by reducing or increasing the intensity and duration of ink grinding.

Mò; Japanese: 墨; Sumi; Korean: 먹 Meok) or Ink Cakes are a type of solid ink (India ink) used traditionally in several East Asian cultures for calligraphy and brush painting. Inksticks are made mainly of soot and animal glue, sometimes with incense or medicinal scents added. To make ink, the inkstick is ground against an inkstone with a small quantity of water to produce a dark liquid which is then applied with an ink brush. Artists and calligraphers may vary the concentration of the resulting ink according to their preferences by reducing or increasing the intensity and duration of ink grinding.

Along with the inkstone, ink brush, and paper, the inkstick is considered one of the Four Treasures of the Study of classical Chinese literary culture.

History

The earliest artifacts of Chinese inks can be dated back to 12th century BC, with charred materials, plant dyes, and animal-based inks being occasionally used, mineral inks being most common. Mineral inks based on materials such as graphite were ground with water and applied with brushes. The mineral origins of Chinese inks were discussed by the Eastern Han dynasty scholar Xu Shen (許慎, 58 – c. 147). In his Shuowen Jiezi, he wrote "Ink, whose semantic component is 'earth', is black." (墨,從土,黑也), indicating that the character for "ink" (墨) is composed of the characters for "black" (黑) and "soil" (土), due to the earthly origins of the dark mineral used in its production.

The transition from graphite inks to soot and charred inks occurred prior to the Shang dynasty. From studies of ink traces in artifacts of various dynasties, it is believed the inks used in the Zhou dynasty are quite similar to those used in the Han dynasty. However, these early inks, up to the Qin dynasty, were likely stored in liquid or powdered forms that have not been well preserved and thus their existence and constitution can only be studied from painted objects and artifacts.[1] Physical proof for these first "modern" Chinese soot and animal glue inks were found in archaeological excavations of tombs dated to the end of the Warring States period around 256 BC. This ink was formed by manual labor into pellets which were ground into ink on top of a flat inkstone using a smaller stone pestle. Many pellet-type inks and grinding implements have been found in Han dynasty tombs, with large ingot-type inks appearing in the late Eastern Han. These latter inks have physical markings which indicate that kneading was used in their production.[1]

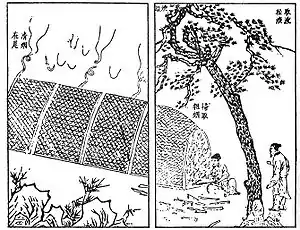

One of the first literary records of inkstick production in Japan is from qimin yaoshu (齊民要術)[2] written during the Northern Wei dynasty. Elaboration of the techniques, technical requirements, and ingredients were also noted in scroll ten of yunlu manchao (雲麓漫鈔)[3] and the "ink" chapter of tiangong kaiwu (天工開物), the notable Ming dynasty encyclopedia by Song Yingxing (宋應星).[4]

Production

In general, inksticks are made of soot and animal glue, with other ingredients occasionally added as preservatives or for aesthetics:

- Soot: Soot is produced by hypoxic burning of oils such as tung oil (桐油), soybean oil, tea seed oil, or lard, or from wood such as pine.[5]

- Animal glue: Egg white, fish skin, or ox hide glues are used to bind the inkstick together.

- Incense and medicines: To improve the physical aesthetics of the inkstick, incense and herb extracts from Traditional Chinese medicine such as clove, comfrey, ash (Fraxinus chinensis) bark, sappanwood, white sandalwood, Oriental sweetgum, or even deer musk, and pearl dust were added. These ingredients may serve as preservatives for the inkstick.

The ingredients are mixed together in precise proportions into a dough and then kneaded until the dough is smooth and even. The dough is then cut and pressed into a mold and slowly dried. Badly made inksticks will crack or craze due to inadequate kneading, imprecise soot to glue ratio, or uneven drying.[6]

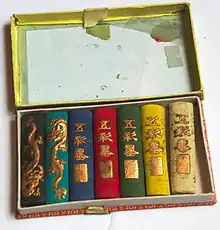

The most common shape for inksticks is rectangular/cuboid though other shapes are sometimes used. Inksticks often have various inscriptions and images incorporated into their design, such as indications of the maker or the type of inkstick, poetry, or an artistic image.

A good inkstick is said to be as hard as stone, with a texture like a rhino, and black like lacquer (堅如石,紋如犀,黑如漆). The grinding surface of a quality inkstick should in reflected light have a sheen that is blueish-purple, black if not so good, and white if bad. The best inksticks make very little noise when grinding due to the fine soot used, which makes the grinding action very smooth, whereas a very loud or scratchy grinding noise indicates an ink of poor quality with a grainy soot. Likewise, a quality inkstick should not damage or scratch the inkstone.

Types

There are many types of inksticks produced. An artist or calligrapher may use a specific ink for a special purpose or to create special effects.

- Oil soot ink is made using the soot of burnt tung oil or various other oils. There is more glue in this type of ink than the other kinds, so it does not spread as much. It gives a warm black color and is good as a general purpose painting and calligraphy ink.

- Pine soot ink is made from the soot of pine wood. It has less glue and so spreads more than oil soot ink. It gives a blueish-black color and is good for calligraphy and gongbi painting.

- Lacquer soot ink is made from the soot of dried raw lacquer. It has a shiny appearance and is most suitable for painting.

- Charcoal ink is made using ordinary wood charcoal. It has the least amount of glue and so spreads on paper more than other inks. It is mainly used for freestyle painting and calligraphy.

- Blueish ink (青墨) is oil or pine soot that has been mixed with other ingredients to produce a subtle blueish-black ink. Mainly used for calligraphy.

- Coloured ink is oil soot ink that has been blended with pigments to create a solid ink of color. Most popular is cinnabar ink, which was reportedly used by Chinese emperors.

An artist might commission a custom ink to suit his/her needs. Medical ink is produced by mixing standard ink with herbal medicines, and can be ground and taken internally. Some inks are made in highly decorative and odd shapes for collectors rather than actual use.

Within each type of ink there are many variations regarding additional ingredients and fineness of the soot. An artist selects the best type of ink suited to their needs depending on discipline, paper type, and so on.

References

- 蔡, 玫芬 (1994), "墨的發展史", 《墨》,文房四寶叢書之四, 彰化市: 彰化社會教育館

- 思勰, 賈 (386-534 A.D. (N.Wei)), 齊民要術 Check date values in:

|date=(help) - 趙, 彥衛 (~1195 A.D.(Song)), 雲麓漫鈔 Check date values in:

|date=(help) - 宋, 應星 (1637 (Ming)), 天工開物 Check date values in:

|date=(help) - Some Typical Ink Sticks, archived from the original on 1999-04-20

- Hui Ink Stick