Clove

Cloves are the aromatic flower buds of a tree in the family Myrtaceae, Syzygium aromaticum. They are native to the Maluku Islands (or Moluccas) in Indonesia, and are commonly used as a spice. Cloves are available throughout the year owing to different harvest seasons in different countries.[2]

| Clove | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Myrtales |

| Family: | Myrtaceae |

| Genus: | Syzygium |

| Species: | S. aromaticum |

| Binomial name | |

| Syzygium aromaticum | |

| Synonyms[1] | |

| |

Botanical features

The clove tree is an evergreen that grows up to 8–12 metres (26–39 ft) tall, with large leaves and crimson flowers grouped in terminal clusters. The flower buds initially have a pale hue, gradually turn green, then transition to a bright red when ready for harvest. Cloves are harvested at 1.5–2 centimetres (0.59–0.79 in) long, and consist of a long calyx that terminates in four spreading sepals, and four unopened petals that form a small central ball.

Uses

Cloves are used in the cuisine of Asian, African, Mediterranean, and the Near and Middle East countries, lending flavor to meats, curries, and marinades, as well as fruit (such as apples, pears, and rhubarb). Cloves may be used to give aromatic and flavor qualities to hot beverages, often combined with other ingredients such as lemon and sugar. They are a common element in spice blends, including pumpkin pie spice and speculoos spices.

In Mexican cuisine, cloves are best known as clavos de olor, and often accompany cumin and cinnamon.[3] They are also used in Peruvian cuisine, in a wide variety of dishes such as carapulcra and arroz con leche.

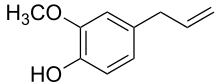

A major component of clove taste is imparted by the chemical eugenol,[4] and the quantity of the spice required is typically small. It pairs well with cinnamon, allspice, vanilla, red wine, basil, onion, citrus peel, star anise, and peppercorns.

Non-culinary uses

The spice is used in a type of cigarette called kretek in Indonesia.[1] Clove cigarettes have been smoked throughout Europe, Asia, and the United States. Since 2009, clove cigarettes have been classified as cigars in the US.[5]

Because of the bioactive chemicals of clove, the spice may be used as an ant repellent.[6]

Cloves can be used to make a fragrant pomander when combined with an orange. When given as a gift in Victorian England, such a pomander indicated warmth of feeling.

Potential medicinal uses and adverse effects

Long-used in traditional medicine, there is evidence that clove oil containing eugenol is effective for toothache pain and other types of pain,[7][8] and one review reported efficacy of eugenol combined with zinc oxide as an analgesic for alveolar osteitis.[9] Studies to determine its effectiveness for fever reduction, as a mosquito repellent, and to prevent premature ejaculation have been inconclusive.[7][8] It remains unproven whether blood sugar levels are reduced by cloves or clove oil.[8] Use of clove for any medicinal purpose has not been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration, and its use may cause adverse effects if taken orally by people with liver disease, blood clotting and immune system disorders, or food allergies.[7]

Traditional medicinal uses

Cloves are used in traditional medicine as the essential oil, which is used as an anodyne (analgesic) mainly for dental emergencies and other disorders.[10] The essential oil is used in aromatherapy.[7]

Adulteration

Clove stalks are slender stems of the inflorescence axis that show opposite decussate branching. Externally, they are brownish, rough, and irregularly wrinkled longitudinally with short fracture and dry, woody texture.

Mother cloves (anthophylli) are the ripe fruits of cloves that are ovoid, brown berries, unilocular and one-seeded.

Blown cloves are expanded flowers from which both corollae and stamens have been detached.

Exhausted cloves have most or all the oil removed by distillation. They yield no oil and are darker in color.[11]

History

Evidence of cloves has been found at Terqa, Syria dating to 1720 BCE[12] In the third century BC, Chinese emperors of the Han Dynasty required those who addressed them to chew cloves to freshen their breath.[13] Cloves reached the Roman world by the first century AD, where they were described by Pliny the Elder.[14] By 176 AD, cloves had reached Egypt.[15]

The first clearly dated archeological find of a clove is substantially later than the written evidence, with two examples found at a trading port in Sri Lanka, dated to around 900-1100 AD.[16]

Cloves were traded by Omani sailors and merchants trading goods from India to the mainland and Africa during the Middle Ages in the profitable Indian Ocean trade.

Until modern times, cloves grew only on a few islands in the Moluccas (historically called the Spice Islands), including Bacan, Makian, Moti, Ternate, and Tidore.[17] In fact, the clove tree that experts believe is the oldest in the world, named Afo, is on Ternate; the tree is between 350 and 400 years old.[18] Tourists are told that seedlings from this very tree were stolen by a Frenchman named Pierre Poivre in 1770, transferred to the Isle de France (Mauritius), and then later to Zanzibar, which was once the world's largest producer of cloves.[18]

Until cloves were grown outside of the Maluku Islands, they were traded like oil, with an enforced limit on exportation.[18] As the Dutch East India Company consolidated its control of the spice trade in the 17th century, they sought to gain a monopoly in cloves as they had in nutmeg. However, "unlike nutmeg and mace, which were limited to the minute Bandas, clove trees grew all over the Moluccas, and the trade in cloves was beyond the limited policing powers of the corporation."[19]

Chemical compounds

Eugenol comprises 72–90% of the essential oil extracted from cloves, and is the compound most responsible for clove aroma.[4][20] Complete extraction occurs at 80 minutes in pressurized water at 125 °C (257 °F).[21] Ultrasound-assisted and microwave-assisted extraction methods provide more rapid extraction rates with lower energy costs.[22]

Other important essential oil constituents of clove oil include acetyl eugenol, beta-caryophyllene, vanillin, crategolic acid, tannins such as bicornin,[4][23] gallotannic acid, methyl salicylate (painkiller), the flavonoids eugenin, kaempferol, rhamnetin, and eugenitin, triterpenoids such as oleanolic acid, stigmasterol, and campesterol and several sesquiterpenes.[24] Eugenol has not been classified for its potential toxicity.[20]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Syzygium aromaticum. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Cloves. |

References

- "Syzygium aromaticum (L.) Merr. & L.M.Perry". Germplasm Resources Information Network (GRIN). Agricultural Research Service (ARS), United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). Retrieved June 9, 2011.

- Yun, Wonjung (13 August 2018). "[Tridge Market Update] Tight Stocks of Quality Cloves Lead to a Price Surge". Tridge. Archived from the original on 14 August 2018. Retrieved 13 August 2018.

- Dorenburg, Andrew and Page, Karen. The New American Chef: Cooking with the Best Flavors and Techniques from Around the World, John Wiley and Sons Inc., 2003

- Kamatou, G. P.; Vermaak, I.; Viljoen, A. M. (2012). "Eugenol--from the remote Maluku Islands to the international market place: a review of a remarkable and versatile molecule". Molecules. 17 (6): 6953–81. doi:10.3390/molecules17066953. PMC 6268661. PMID 22728369.

- "Flavored Tobacco". FDA. Retrieved September 7, 2012.

- "Get Rid of Ants 24". getridofanst24. Archived from the original on 2015-04-28.

- "Clove". Drugs.com. 5 March 2018. Retrieved 9 November 2018.

- "Clove". MedlinePlus, U.S. National Library of Medicine and National Institutes of Health. 2014. Retrieved August 18, 2014.

- Taberner-Vallverdú, M.; Nazir, M.; Sanchez-Garces, M. Á.; Gay-Escoda, C. (2015). "Efficacy of different methods used for dry socket management: A systematic review". Medicina Oral Patología Oral y Cirugia Bucal. 20 (5): e633–e639. doi:10.4317/medoral.20589. PMC 4598935. PMID 26116842.

- Balch, Phyllis and Balch, James. Prescription for Nutritional Healing, 3rd ed., Avery Publishing, 2000, p. 94

- Bisset, N. G. (1994). Herbal drugs and phyotpharmaceuticals, Medpharm. Stuttgart: Scientific Publishers.

- Scott, Ashley; Power, Robert C.; Altmann-Wendling, Victoria; Artzy, Michal; Martin, Mario A. S.; Eisenmann, Stefanie; Hagan, Richard; Salazar-García, Domingo C.; Salmon, Yossi; Yegorov, Dmitry; Milevski, Ianir (2020-12-17). "Exotic foods reveal contact between South Asia and the Near East during the second millennium BCE". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 118 (2): e2014956117. doi:10.1073/pnas.2014956117. hdl:10550/76877. ISSN 0027-8424. PMID 33419922. S2CID 231305886.

- Andaya, Leonard Y. (1993). "1: Cultural State Formation in Eastern Indonesia". In Reid, Anthony (ed.). Southeast Asia in the early modern era: trade, power, and belief. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-8093-5.

- Lape, Peter V. (5 November 2010). "Political dynamics and religious change in the late pre-colonial Banda Islands, Eastern Indonesia". World Archaeology. 32 (1): 138–155. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.500.4009. doi:10.1080/004382400409934. S2CID 19503031.

- Pickersgill, Barbara (2005). Prance, Ghillean; Nesbitt, Mark (eds.). The Cultural History of Plants. Routledge. p. 159. ISBN 0415927463.

- Kingwell-Banham, Eleanor. "World's oldest clove? Here's what our find in Sri Lanka says about the early spice trade". The Conversation.

- Turner, Jack (2004). Spice: The History of a Temptation. Vintage Books. pp. xxvii–xxviii. ISBN 978-0-375-70705-6.

- Worrall, Simon (23 June 2012). "The world's oldest clove tree". BBC News Magazine. Retrieved June 24, 2012.

- Krondl, Michael. The Taste of Conquest: The Rise and Fall of the Three Great Cities of Spice. New York: Ballantine Books, 2007.

- "Eugenol". PubChem, US National Library of Medicine. 2 November 2019. Retrieved 10 November 2019.

- Rovio, S.; Hartonen, K.; Holm, Y.; Hiltunen, R.; Riekkola, M.‐L. (7 February 2000). "Extraction of clove using pressurized hot water". Flavour and Fragrance Journal. 14 (6): 399–404. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-1026(199911/12)14:6<399::AID-FFJ851>3.0.CO;2-A.

- Khalil, A.A.; ur Rahman, U.; Khan, M.R.; Sahar, A.; Mehmood, T.; Khan, M. (2017). "Essential oil eugenol: sources, extraction techniques and nutraceutical perspectives". RSC Advances. 7 (52): 32669–32681. doi:10.1039/C7RA04803C.

- Li-Ming Bao, Eerdunbayaer; Nozaki, Akiko; Takahashi, Eizo; Okamoto, Keinosuke; Ito, Hideyuki; Hatano, Tsutomu (2012). "Hydrolysable Tannins Isolated from Syzygium aromaticum: Structure of a New C-Glucosidic Ellagitannin and Spectral Features of Tannins with a Tergalloyl Group". Heterocycles. 85 (2): 365–381. doi:10.3987/COM-11-12392.

- Chinese Herbal Medicine: Materia Medica, Third Edition by Dan Bensky, Steven Clavey, Erich Stoger, and Andrew Gamble. 2004