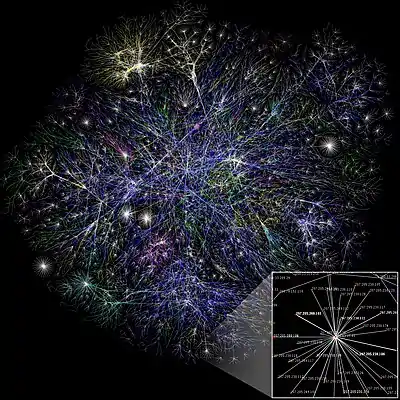

Internet backbone

The Internet backbone may be defined by the principal data routes between large, strategically interconnected computer networks and core routers of the Internet. These data routes are hosted by commercial, government, academic and other high-capacity network centers, as well as the Internet exchange points and network access points, that exchange Internet traffic between the countries, continents, and across the oceans. Internet service providers, often Tier 1 networks, participate in Internet backbone traffic by privately negotiated interconnection agreements, primarily governed by the principle of settlement-free peering.

The Internet, and consequently its backbone networks, do not rely on central control or coordinating facilities, nor do they implement any global network policies. The resilience of the Internet results from its principal architectural features, most notably the idea of placing as few network state and control functions as possible in the network elements and instead relying on the endpoints of communication to handle most of the processing to ensure data integrity, reliability, and authentication. In addition, the high degree of redundancy of today's network links and sophisticated real-time routing protocols provide alternate paths of communications for load balancing and congestion avoidance.

The largest providers, known as Tier 1 providers, have such comprehensive networks that they do not purchase transit agreements from other providers.[1] As of 2019, there are six Tier 1 providers in the telecommunications industry: CenturyLink (Level 3), Telia Carrier, NTT, GTT, Tata Communications, and Telecom Italia.[2]

Infrastructure

The Internet backbone consists of many networks owned by numerous companies. Optical fiber trunk lines consists of many fiber cables bundled to increase capacity, or bandwidth. Fiber-optic communication remains the medium of choice for Internet backbone providers for several reasons. Fiber-optics allow for fast data speeds and large bandwidth, they suffer relatively little attenuation, allowing them to cover long distances with few repeaters, and they are also immune to crosstalk and other forms of electromagnetic interference which plague electrical transmission. The real-time routing protocols and redundancy built into the backbone is also able to reroute traffic in case of a failure.[3] The data rates of backbone lines have increased over time. In 1998,[4] all of the United States' backbone networks had utilized the slowest data rate of 45 Mbit/s. However, technological improvements allowed for 41 percent of backbones to have data rates of 2,488 Mbit/s or faster by the mid 2000s.[5]

History

The first packet-switched computer networks, the NPL network and the ARPANET were interconnected in 1973 via University College London.[6] The ARPANET used a backbone of routers called Interface Message Processors. Other packet-switched computer networks proliferated starting in the 1970s, eventually adopting TCP/IP protocols, or being replaced by newer networks. The National Science Foundation created the National Science Foundation Network (NSFNET) in 1986 by funding six networking sites using 56kbit/s interconnecting links, with peering to the ARPANET. In 1987, this new network was upgraded to 1.5Mbit/s T1 links for thirteen sites. These sites included regional networks that in turn connected over 170 other networks. IBM, MCI and Merit upgraded the backbone to 45Mbit/s bandwidth (T3) in 1991.[7] The combination of the ARPANET and NSFNET became known as the Internet. Within a few years, the dominance of the NSFNet backbone led to the decommissioning of the redundant ARPANET infrastructure in 1990.

In the early days of the Internet, backbone providers exchanged their traffic at government-sponsored network access points (NAPs), until the government privatized the Internet, and transferred the NAPs to commercial providers.[1]

Modern backbone

Because of the overlap and synergy between long-distance telephone networks and backbone networks, the largest long-distance voice carriers such as AT&T Inc., MCI (acquired in 2006 by Verizon), Sprint, and CenturyLink also own some of the largest Internet backbone networks. These backbone providers sell their services to Internet service providers (ISPs).[1]

Each ISP has its own contingency network and is equipped with an outsourced backup. These networks are intertwined and crisscrossed to create a redundant network. Many companies operate their own backbones which are all interconnected at various Internet exchange points (IXPs) around the world.[8] In order for data to navigate this web, it is necessary to have backbone routers—routers powerful enough to handle information—on the Internet backbone and are capable of directing data to other routers in order to send it to its final destination. Without them, information would be lost.[9]

Economy of the backbone

Peering agreements

Backbone providers of roughly equivalent market share regularly create agreements called peering agreements, which allow the use of another's network to hand off traffic where it is ultimately delivered. Usually they do not charge each other for this, as the companies get revenue from their customers regardless.[1][10]

Regulation

Antitrust authorities have acted to ensure that no provider grows large enough to dominate the backbone market. In the United States, the Federal Communications Commission has decided not to monitor the competitive aspects of the Internet backbone interconnection relationships as long as the market continues to function well.[1]

Transit agreements

Backbone providers of unequal market share usually create agreements called transit agreements, and usually contain some type of monetary agreement.[1][10]

Regional backbone

Egypt

During the Egyptian revolution of 2011, the government of Egypt shut down the four major ISPs on January 27, 2011 at approximately 5:20 p.m. EST.[11] Evidently the networks had not been physically interrupted, as the Internet transit traffic through Egypt was unaffected. Instead, the government shut down the Border Gateway Protocol (BGP) sessions announcing local routes. BGP is responsible for routing traffic between ISPs.[12]

Only one of Egypt's ISPs was allowed to continue operations. The ISP Noor Group provided connectivity only to Egypt's stock exchange as well as some government ministries.[11] Other ISPs started to offer free dial-up Internet access in other countries.[13]

Europe

Europe is a major contributor to the growth of the international backbone as well as a contributor to the growth of Internet bandwidth. In 2003, Europe was credited with 82 percent of the world's international cross-border bandwidth.[14] The company Level 3 Communications began to launch a line of dedicated Internet access and virtual private network services in 2011, giving large companies direct access to the tier 3 backbone. Connecting companies directly to the backbone will provide enterprises faster Internet service which meets a large market demand.[15]

Caucasus

Certain countries around the Caucasus have very simple backbone networks; for example, in 2011, a woman in Georgia pierced a fiber backbone line with a shovel and left the neighboring country of Armenia without Internet access for 12 hours. The country has since made major developments to the fiber backbone infrastructure, but progress is slow due to lack of government funding.[16]

Japan

Japan's Internet backbone needs to be very efficient due to high demand for the Internet and technology in general. Japan had over 86 million Internet users in 2009, and was projected to climb to nearly 91 million Internet users by 2015. Since Japan has a demand for fiber to the home, Japan is looking into tapping a fiber-optic backbone line of Nippon Telegraph and Telephone (NTT), a domestic backbone carrier, in order to deliver this service at cheaper prices.[17]

China

In some instances, the companies that own certain sections of the Internet backbone's physical infrastructure depend on competition in order to keep the Internet market profitable. This can be seen most prominently in China. Since China Telecom and China Unicom have acted as the sole Internet service providers to China for some time, smaller companies cannot compete with them in negotiating the interconnection settlement prices that keep the Internet market profitable in China. This imposition of discriminatory pricing by the large companies then results in market inefficiencies and stagnation, and ultimately affects the efficiency of the Internet backbone networks that service the nation.[18]

See also

Further reading

- Greenstein, Shane. 2020. "The Basic Economics of Internet Infrastructure." Journal of Economic Perspectives, 34 (2): 192-214. DOI: 10.1257/jep.34.2.192

References

- Jonathan E. Nuechterlein; Philip J. Weiser. Digital Crossroads.

- Zmijewski, Earl (2017). "A Baker's Dozen, 2016 Edition". Dyn Research IP Transit Intelligence Global Rankings.

- Nuechterlein, Jonathan E., author. (5 July 2013). Digital crossroads : telecommunications law and policy in the internet age. ISBN 978-0-262-51960-1. OCLC 827115552.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Kesan, Jay P.; Shah, Rajiv C. (2002). "Shaping Code". SSRN 328920.

- Malecki, Edward J. (October 2002). "The Economic Geography of the Internet's Infrastructure". Economic Geography. 78 (4): 399–424. doi:10.2307/4140796. ISSN 0013-0095. JSTOR 4140796.

- Kirstein, P.T. (1999). "Early experiences with the Arpanet and Internet in the United Kingdom" (PDF). IEEE Annals of the History of Computing. 21 (1): 38–44. doi:10.1109/85.759368. ISSN 1934-1547. S2CID 1558618.

- Kende, M. (2000). "The Digital Handshake: Connecting Internet Backbones". Journal of Communications Law & Policy. 11: 1–45.

- Tyson, J. "How Internet Infrastructure Works". Archived from the original on 14 June 2011. Retrieved 9 February 2011.

- Badasyan, N.; Chakrabarti, S. (2005). "Private peering, transit and traffic diversion". Netnomics : Economic Research and Electronic Networking. 7 (2): 115. doi:10.1007/s11066-006-9007-x. S2CID 154591220.

- "Internet Backbone". Topbits Website. Archived from the original on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 9 February 2011.

- Singel, Ryan (28 January 2011). "Egypt Shut Down Its Net With a Series of Phone Calls". Wired. Archived from the original on 1 May 2011. Retrieved 30 April 2011.

- Van Beijnum, Iljitsch. "How Egypt did (and your government could) shut down the Internet". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on 26 April 2011. Retrieved 30 April 2011.

- Murphy, Kevin. "DNS not to blame for Egypt blackout". Domain Incite. Archived from the original on 4 April 2011. Retrieved 30 April 2011.

- "Global Internet backbone back up to speed for 2003 after dramatic slow down in 2002". TechTrends. 47 (5): 47. 2003.

- "Europe - Level 3 launches DIA, VPN service portfolios in Europe". Europe Intelligence Wire. 28 January 2011.

- Lomsadze, Giorgi (8 April 2011). "A Shovel Cuts Off Armenia's Internet". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 25 December 2014. Retrieved 16 April 2011.

- "Japan telecommunications report - Q2 2011". Japan Telecommunications Report (1). 2011.

- Li, Meijuan; Zhu, Yajie (2018). "Research on the problems of interconnection settlement in China's Internet backbone network". Procedia Computer Science. 131: 153–157. doi:10.1016/j.procs.2018.04.198 – via Elsevier Science Direct.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Maps of Internet backbone networks. |