Ischigualasto Formation

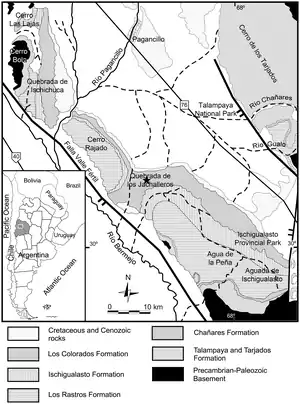

The Ischigualasto Formation is a Late Triassic fossiliferous formation and Lagerstätte in the Ischigualasto-Villa Unión Basin of the southwestern La Rioja Province and northeastern San Juan Province in northwestern Argentina. The formation dates to the Carnian age and ranges between 231.7 and 225 Ma, based on ash bed dating.

| Ischigualasto Formation Stratigraphic range: Carnian 231.7–225 Ma | |

|---|---|

Valle Pintado, Ischigualasto Formation | |

| Type | Geological formation |

| Unit of | Agua de la Peña Group |

| Sub-units | Quebrada de la Sal, Valle de la Luna, Cancha de Bochas & La Peña Members |

| Underlies | Los Colorados Formation |

| Overlies | Los Rastros Formation |

| Thickness | Up to 900 m (3,000 ft) |

| Lithology | |

| Primary | Sandstone, mudstone |

| Other | Tuff, conglomerate |

| Location | |

| Coordinates | 29.6°S 68.1°W |

| Approximate paleocoordinates | 46.0°S 40.2°W |

| Region | La Rioja Province & San Juan Provinces |

| Country | |

| Extent | Ischigualasto-Villa Unión Basin |

| Type section | |

| Named for | Cacán: "Place where the moon alights" |

Ischigualasto Formation (Argentina) | |

The up to 900 metres (3,000 ft) thick formation is part of the Agua de la Peña Group, overlies Los Rastros Formation and is overlain by Los Colorados Formation. The formation is subdivided into four members, from old to young; La Peña, Cancha de Bochas, Valle de la Luna and Quebrada de la Sal. The sandstones, mudstones, conglomerates and tuffs of the formation were deposited in a humid alluvial to fluvial floodplain environment, characterized by strongly seasonal rainfall.

The Ischigualasto Formation is an important paleontological unit and considered a Lagerstätte, as it preserves several genera of early dinosaurs, other archosaurs, synapsids, and temnospondyls of the Late Triassic. Coprolites and fossil wood also have been found in the formation. The formation crops out in the in 1967 established Ischigualasto Provincial Park, which was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2000.

Etymology

The name Ischigualasto is derived from the extinct Cacán language, spoken by an indigenous group referred to as the Diaguita by the Spanish conquistadors and means "place where the moon alights".[1] The genus Ischigualastia and the species Herrerasaurus ischigualastensis, Pseudochampsa ischigualastensis, Pelorocephalus ischigualastensis and Protojuniperoxylon ischigualastianus were named after the formation.

Geology

The formation represents the second syn-rift period in the Ischigualasto-Villa Unión Basin,[2] where the total thickness of Triassic sediments amounts to 3.5 kilometres (11,000 ft).[3] The formation is exposed in the Ischigualasto Provincial Park of La Rioja and San Juan Provinces. In the neighboring Talampaya National Park, the formation is thin and covered by recent sediments.[4] The formation, part of the Agua de la Peña Group, overlies Los Rastros Formation and is overlain by Los Colorados Formation. The Ischigualasto Formation strongly contrasts with the bounding formation in color.[5] The total thickness amounts to 900 metres (3,000 ft).[2]

The Ischigualasto Formation comprises a sequence of fluvial channel sandstones with well-drained floodplain sandstones and mudstones, dominated by rivers and strongly seasonal rainfall has been estimated at time of deposition. The formation dates to the Carnian Pluvial Event. Interlayered volcanic ash layers above the base and below the top of the formation provide chronostratigraphic control and have yielded ages of 231.4 ± 0.3 Ma and 225.9 ± 0.9 Ma respectively.[6]

The formation is approximately coeval with the upper Santa Maria Formation of the Paraná Basin in southeastern Brazil, the Pekin Formation of the United States and the lower Maleri Formation of India.[7]

Subdivision

The Ischigualasto Formation is subdivided into four members, from top to bottom:[8]

- Quebrada de la Sal ~60 metres (200 ft)

- Valle de la Luna ~450 metres (1,480 ft)

- Cancha de Bochas ~130 metres (430 ft)

- La Peña ~50 metres (160 ft)

Paleontological significance

The Ischigualasto Formation is highly fossiliferous and its unique paleontological characteristics made it a Lagerstätte; a stratigraphic unit containing a diverse faunal assemblage. The paleontological importance led to the establishment of the Ischigualasto Provincial Park, a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 2000.

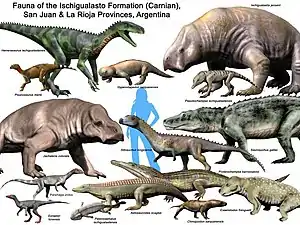

The Ischigualasto Formation contains Late Triassic (Carnian) deposits (231.4 -225.9 million years before the present[9]), with some of the oldest known dinosaur remains, which are the world's foremost with regards to quality, number and importance.

Rhynchosaurs and cynodonts (especially rhynchosaur Hyperodapedon and cynodont Exaeretodon[9]) are by far the predominant findings among the tetrapod fossils in the park. A study from 1993 found dinosaur specimens to comprise only 6% of the total tetrapod sample;[10] subsequent discoveries increased this number to approximately 11% of all findings.[9] Carnivorous dinosaurs are the most common terrestrial carnivores of the Ischigualasto Formation, with herrerasaurids comprising 72% of all recovered terrestrial carnivores.[9] The carnivorous archosaur Herrerasaurus is the most numerous of these dinosaur fossils. Another important putative dinosaur with primitive characteristics is Eoraptor lunensis, found in Ischigualasto in the early 1990s.

Petrified tree trunks of Protojuniperoxylon ischigualastianus of more than 40 m (130 ft) tall attest to a rich vegetation at that time. Fossil ferns and horsetails have also been found in the formation.

Coprolites were found in Valle Pintado in the upper part of the formation. Analysis of the coprolites revealed that plant remains were absent and bone material and apatite were sparse. The most likely candidate to have produced these fossil feces has been suggest as the most common reptile in the formation; Herrerasaurus.[11]

Fossil content

Dinosaurs

The fossils of an undescribed species of theropod are present in San Juan Province.[12]

| Dinosaurs | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Species | Province | Member | Material | Notes | Image |

| Chromogisaurus | C. novasi | San Juan | Cancha de Bochas | Partial skeleton including limb bones, pelvic bones and caudal vertebrae | A 2 metres (6.6 ft) long saturnaliine guaibasaurid known from a partial skeleton lacking the skull. It includes elements of the front and hind limbs; the pelvis and two caudal vertebrae.[13] | |

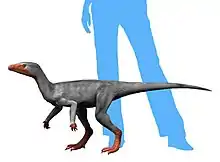

| Eodromaeus | E. murphi | San Juan | Valle de la Luna | A nearly complete skeleton and another partial skeleton | A basal theropod with a total length of about 1.2 meters (3.9 feet) from nose to tail, and a weight of about 5 kilograms (11 pounds). The trunk was long and slender. It is unknown how fast Eodromaeus could run, but it has been suggested to about 30 kilometres per hour (19 mph). The forelimbs were much shorter than the hind limbs, ending in hands with 5 digits. Digits IV and V (the ring finger and little finger in humans) were very reduced in size.[9] |  |

| Eoraptor | E. lunensis | San Juan | Cancha de Bochas | Two nearly complete skeletons[14] | An omnivorous, lightly-built, basal eusaurischian, close to the ancestry of theropods[13] and sauropodomorphs.[9] Eoraptor had a slender body that grew to about 1 meter (3.3 feet) in length, with an estimated weight of about 10 kilograms (22 pounds). It has a lightly built skull with a slightly enlarged external naris. Like the coelophysoids which would appear millions of years later, Eoraptor has a kink in its upper jaws, between the maxilla and the premaxilla.[12] |  |

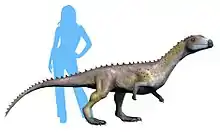

| Herrerasaurus | H. ischigualastensis | San Juan | Cancha de Bochas | "Various partial skeletons, including a complete skull and mandible."[14] | A herrerasaur with a length estimated at 3 to 6 meters (9.8 to 19.7 ft), and its hip height at more than 1.1 meters (3.6 feet). It may have weighed around 210–350 kg (460–770 lb). In a large specimen, at first thought to belong to a separate (now discredited) genus, Frenguellisaurus, the skull measured 56 cm (22 in) in length. Smaller specimens had skulls about 30 centimetres (12 in) long. Its size indicates it would have preyed upon small and medium-sized plant-eaters. Herrerasaurus itself may have been preyed upon by giant rauisuchids; puncture wounds were found in one skull.[12] |  |

| Panphagia | P. protos | San Juan | La Peña | A guaibasaurid that is one of the most basal known genera of sauropodomorphs.[13][15][16] Panphagia is currently known from the disarticulated remains of one partially grown individual of about 1.30 meters (4.3 feet) long. Portions of the skull, vertebrae, pectoral girdle, pelvic girdle, and hind limb bones have been recovered. The russet-colored fossils were embedded in a greenish sandstone matrix and took several years to prepare and describe.[15][12] |  | |

| Sanjuansaurus | S. gordilloi | San Juan | Cancha de Bochas La Peña |

An incomplete skeleton[17] | A herrerasaur comparable in size to a medium-sized Herrerasaurus, with a thigh bone that was 395 millimeters (15.6 inches) long and a tibia that is 260 millimeters (10 inches) in length.[17] |  |

| An unnamed herrerasaur[13] | Unnamed | Specimen MACN-PV 18649a[13] | A herrerasaur distinct from Herrerasaurus, Staurikosaurus and Sanjuansaurus.[13] | |||

Other archosauromorphs

| Non-dinosaurian archosauromorphs[13][18] | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Species | Province | Member | Material | Notes | Images |

| Aetosauroides | A. scagliai | San Juan | Cancha de Bochas | An aetosaur that is one of four aetosaurs known from South America, the others being Neoaetosauroides, Chilenosuchus and Aetobarbakinoides. It was once proposed to be synonymous with Stagonolepis. |  | |

| Hyperodapedon | H. sanjuanensis | San Juan | A heavily-built, stocky hyperodapedontine hyperodapedont around 1.3 meters (4.3 feet) in length. Apart from its beak, this rhynchosaur had several rows of heavy teeth on each side of the upper jaw, and a single row on each side of the lower jaw, creating a powerful chopping action when it ate. It is believed to have been herbivorous, feeding mainly on seed ferns. |  | ||

| Ignotosaurus | I. fragilis | San Juan | Cancha de Bochas | Right ilium[18] | A little-known silesaur[18] |  |

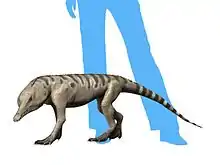

| Pisanosaurus | P. mertii | La Rioja | "Fragmentary skull and skeleton"[19] | A non-dinosaurian dinosauriform known from a single partial skeleton. Pisanosaurus was a small, lightly-built, ground-dwelling herbivore approximately 1 meter (3 feet 3 inches) in length. Its weight was between 2.27 and 9.1 kg (5.0 and 20.1 lb). These estimates vary due to the incompleteness of the holotype specimen PVL 2577. It was originally believed to be an early species of ornithischian dinosaur, but recent studies have proven it to be a non-dinosaurian dinosauriform closely related to the silesaurs (possibly a silesaur itself).[12] |  | |

| Proterochampsa | P. barrionuevoi | San Juan | Cancha de Bochas | A proterochampsid known from a 44 centimetres (17 in) skull. It could have grown up to 3.5 m (11 ft). | ||

| Pseudochampsa | P. ischigualastensis | San Juan | Cancha de Bochas | An articulated incomplete skeleton[20] | A proterochampsid originally described a species of Chanaresuchus,[20] subsequently made the type species of a separate genus.[21] |  |

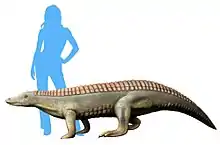

| Saurosuchus | S. galilei | San Juan | Cancha de Bochas | A prestosuchid with a length of around 6 to 9 meters (20 to 30 ft) in total body length. Dorsal osteoderms run along the back of Saurosuchus. There are two rows to either side of the midline, with each leaf-shaped osteoderm joining tightly with the ones in front of and behind it. It has a deep, laterally compressed skull. The teeth are large, recurved, and serrated. The skull is wide at its back and narrows in front of the eyes. |  | |

| Sillosuchus | S. longicervix | San Juan | Cancha de Bochas | A shuvosaurid which could grow to large sizes. It is the only shuvosaurid currently known from outside North America.[22] |  | |

| Teyumbaita | Unnamed | La Rioja | Fossils of multiple specimens[23] | A rhynchosaur. | ||

| Trialestes | T. romeri | La Rioja San Juan |

Cancha de Bochas | The earliest known crocodylomorph, once believed to be a primitive dinosaur |  | |

| Venaticosuchus | V. rusconii | La Rioja | A medium-sized ornithosuchid, reaching up to 2 m (6.6 ft) in length.[18] |  | ||

| An unnamed lagerpetid | Unnamed | San Juan | Distal end of the left femur[18] | A basal dinosauromorph[24][18] | ||

| An unnamed large-bodied crocodylomorph[25] | Unnamed | Cancha de Bochas[25] | Five incomplete skeletons (specimens PVSJ 846, PVSJ 1078, PVSJ 1088, PVSJ 1089 and PVSJ 1090)[25] | |||

Synapsids

| Synapsids[13][18] | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Species | Province | Member | Material | Notes | Images |

| Chiniquodon | C. sanjuanensis, C. cf. theotonicus | San Juan | Cancha de Bochas | A carnivorous, dog-sized chiniquodontid that was a predatory cynodont being similar in ecological niche as the predatory dinosaurs it coexisted with[26][27] |  | |

| Diegocanis | D. elegans | San Juan | Cancha de Bochas | Partial skull, represented by the snout and the orbital region, with partially preserved upper dentition[26] | A little-known ecteniniid | |

| Ecteninion | E. lunensis | San Juan | Cancha de Bochas | A carnivorous ecteniniid known from a nearly complete skull of about 11 centimetres (4.3 in) in length | ||

| Exaeretodon | E. argentinus | San Juan | Cancha de Bochas | A gomphodontosuchine traversodont up to 1.8 meters (5.9 feet) long, with a specialized grinding action when feeding. Another point of interest is that these cynodonts had deciduous teeth, which is a characteristic of mammals and means that babies could not chew, and required specialized parental care. Only older juveniles had permanent teeth. |  | |

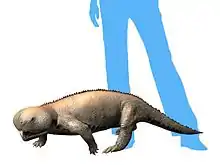

| Ischigualastia | I. jenseni | San Juan | Cancha de Bochas | A stahleckeriine stahleckeriid that was an enormous dicynodont with a short, high skull, and lacking tusks. It is regarded as larger than its later, more famous relative Placerias. |  | |

| Jachaleria | J. colorata | A large dicynodont perhaps 3 metres (9.8 ft) in length and with an estimated mass of 300 kilograms (660 lb), making it close in size to Dinodontosaurus[18] | ||||

| cf. Probainognathus | Indeterminate | A small probainognathid that had an incipient squamosal-dentary jaw-cranium joint, which is a clearly mammalian anatomical feature. Known from about three dozen specimens, this creature was only about 10 centimetres (3.9 in) long. |  | |||

| Pseudotherium[28] | P. argentinus[28] | San Juan | La Peña | Specimen PVSJ 882 (a cranium)[18][29] | A probainognathian cynodont closely related to tritylodontids[29] | |

Temnospondyls

| Temnospondyls[13][18] | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Species | Province | Member | Material | Notes | Images |

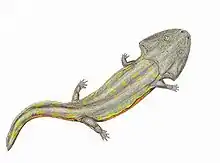

| Pelorocephalus | P. ischigualastensis | A chigutisaurid based on too little material. The largest individuals are estimated to have been over 107 centimetres (42 in) in length. |  | |||

| Promastodonsaurus | P. bellmanni | A little-known mastodonsaur | ||||

Color key

|

Notes Uncertain or tentative taxa are in small text; |

See also

- Quebrada del Barro Formation, contemporaneous fossiliferous formation of the Marrayel-El Carrizal Basin

- Candelária Formation, contemporaneous fossiliferous formation of the Paraná Basin

- Molteno Formation, contemporaneous fossiliferous formation of the Karoo Basin in southern Africa

- Fremouw Formation, contemporaneous fossiliferous formation of Antarctica

- Denmark Hill Insect Bed, contemporaneous fossiliferous unit of Queensland, Australia

- Madygen Formation, contemporaneous Lagerstätte of Central Asia

References

- (in Spanish) El lugar donde se posa la luna

- Aceituno Cieri et al., 2015, p.60

- Schencman, 2015, p.220

- Balabusic et al., 2001, p.26

- Monetta et al., 2000, p.644

- Wallace, 2018, p.6

- Lecuona et al., 2016, p.585

- Martínez et al. 2013b, p. 16.

- Martínez et al. 2011.

- Rogers et al. 1993.

- Hollocher et al., 2005, p.62

- Weishampel et al. 2004, pp. 527–528.

- Ezcurra 2010.

- Weishampel et al. 2004, p. 26, Table 2.1.

- Martínez et al. 2009.

- Cabreira et al. 2011.

- Alcober et al. 2010.

- Martínez et al. 2013b.

- Weishampel et al. 2004, p. 326, Table 14.1.

- Trotteyn et al. 2012.

- Trotteyn & Ezcurra 2014.

- Alcober & Parrish, 2010, p.548

- Julia B. Desojo; Lucas E. Fiorelli; Martín D. Ezcurra; Agustín G. Martinelli; Jahandar Ramezani; Átila. A. S. Da Rosa; M. Belén von Baczko; M. Jimena Trotteyn; Felipe C. Montefeltro; Miguel Ezpeleta; Max C. Langer (2020). "The Late Triassic Ischigualasto Formation at Cerro Las Lajas (La Rioja, Argentina): fossil tetrapods, high-resolution chronostratigraphy, and faunal correlations". Scientific Reports. 10 (1): Article number 12782. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-67854-1. PMC 7391656. PMID 32728077.

- Langer et al. 2013.

- Juan Martín Leardi; Imanol Yáñez; Diego Pol (2020). "South American Crocodylomorphs (Archosauria; Crocodylomorpha): A review of the early fossil record in the continent and its relevance on understanding the origins of the clade". Journal of South American Earth Sciences. 104: Article 102780. doi:10.1016/j.jsames.2020.102780.

- Martínez et al. 2013.

- Martínez & Forster, 1996, p.285

- Wallace et al., 2019

- Wallace, 2018, p.10

Bibliography

- Geology

- Aceituno Cieri, P.; M.E. Zeballos; R.J. Rocca; R.D. Martino, and C. Carignano. 2015. Condicionantes geológicos en el cruce de la sierra de Valle Fértil. San Juan - Geological constraints at the crossing of sierra Valle Fertil. San Juan. Revista de Geología Aplicada a la Ingeniería y al Ambiente 35. 57–69.

- Schencman, Laura Jazmín; Carina Colombi; Paula Santi Malnis, and Carlos Oscar Limarino. 2015. Diagenesis and provenance of the Los Colorados formation (Norian), Ischigualasto- Villa Unión basin, Northwest of Argentina. Revista de la Asociación Geológica Argentina 72. 219–234. Accessed 2019-03-28.

- Balabusic, Ana M., et al. 2001. Plan de Manejo del Parque Nacional Talampaya, 1–68. Administración de Parques Nacionales. Accessed 2019-03-28.

- Monetta, A.; J. Baraldo; A. Cardinali; R. Weidmann, and M. Lanzilotti. 2000. Distribución y características del magmatismo intratriasico de Ischigualasto, San Juan, Argentina, 644–648. IX Congreso Geológico Chileno. Accessed 2019-03-28.

- Paleontology

- Wallace, Rachel V.S.; Ricardo Martínez, and Timothy Rowe. 2019. First record of a basal mammaliamorph from the early Late Triassic Ischigualasto Formation of Argentina. PLoS ONE 14. e0218791. Accessed 2020-03-25. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0218791

- Wallace, Rachel Veronica Simon. 2018. A new close mammal relative and the origin and evolution of the mammalian central nervous system (PhD thesis), 1–224. The University of Texas at Austin. Accessed 2019-03-29.

- Lecuona, A.; M.D. Ezcurra, and R.B. Irmis. 2016. Revision of the early crocodylomorph Trialestes romeri (Archosauria, Suchia) from the lower Upper Triassic Ischigualasto Formation of Argentina: one of the oldest-known crocodylomorphs. Papers in Palaeontology 2. 585–622. Accessed 2019-03-29.

- Trotteyn, María Jimena, and Martín D. Ezcurra. 2014. Osteology of Pseudochampsa ischigualastensis gen. et comb. nov. (Archosauriformes: Proterochampsidae) from the Early Late Triassic Ischigualasto Formation of Northwestern Argentina. PLoS ONE 9. 1–37. Accessed 2019-03-29.

- Martínez, Ricardo N.; Eliana Fernández, and Oscar A. Alcober. 2013. A new non-mammaliaform eucynodont from the Carnian-Norian Ischigualasto Formation, Northwestern Argentina. Revista Brasileira de Paleontologia 16. 61–76. Accessed 2019-03-29.

- Martínez, Ricardo N.; Cecilia Apaldetti; Oscar A. Alcober; Carina E. Colombi; Paul C. Sereno; Eliana Fernández; Paula Santi Malnis; Gustavo A. Correa, and Diego Abelin. 2013. Vertebrate succession in the Ischigualasto Formation. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology Memoir 12: Basal sauropodomorphs and the vertebrate fossil record of the Ischigualasto Formation (Late Triassic: Carnian-Norian) of Argentina. 10–30. Accessed 2019-03-29.

- Trotteyn, María J.; Ricardo N. Martínez, and Oscar A. Alcober. 2012. A new proterochampsid Chanaresuchus ischigualastensis (Diapsida, Archosauriformes) in the early Late Triassic Ischigualasto Formation, Argentina. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 32. 485–489. Accessed 2019-03-29.

- Cabreira, Sergio F.; Cesar L. Schultz; Jonathas S. Bittencourt; Marina B. Soares; Daniel C. Fortier; Lúcio R. Silva, and Max C. Langer. 2011. New stem-sauropodomorph (Dinosauria, Saurischia) from the Triassic of Brazil. Naturwissenschaften 98. 1035–1040. Accessed 2019-03-29.

- Martínez, Ricardo N.; Paul C. Sereno; Oscar A. Alcober; Carina E. Colombi; Paul R. Renne; Isabel P. Montañez, and Brian S. Currie. 2011. A Basal Dinosaur from the Dawn of the Dinosaur Era in Southwestern Pangaea. Science 331. 206–210. Accessed 2019-03-29.

- Alcober, Oscar A., and Ricardo N. Martínez. 2010. A new herrerasaurid (Dinosauria, Saurischia) from the Upper Triassic Ischigualasto Formation of northwestern Argentina. ZooKeys 63. 55–81. Accessed 2019-03-29.

- Alcober, Oscar A., and J. Parrish. 2010. A new poposaurid from the Upper Triassic of Argentina. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 17. 548–556. Accessed 2019-03-29.

- Ezcurra, Martín D. 2010. A new early dinosaur (Saurischia: Sauropodomorpha) from the Late Triassic of Argentina: a reassessment of dinosaur origin and phylogeny. Journal of Systematic Palaeontology 8. 371–425. Accessed 2019-03-29.

- Martínez, Ricardo N., and Oscar A. Alcober. 2009. A Basal Sauropodomorph (Dinosauria: Saurischia) from the Ischigualasto Formation (Triassic, Carnian) and the Early Evolution of Sauropodomorpha. PLoS ONE 4. 1–12. Accessed 2019-03-29.

- Hollocher, K.T.; O.A. Alcober; C.E. Colombi, and T.C. Hollocher. 2005. Carnivore coprolites from the Upper Triassic Ischigualasto Formation, Argentina: chemistry, mineralogy, and evidence for rapid initial mineralization. Palaios 20. 51–63. Accessed 2019-03-29.

- Martínez, R.N., and C.A. Forster. 1996. The skull of Probelesodon sanjuanensis, sp. nov., from the Late Triassic Ischigualasto Formation of Argentina. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 16. 285–291. Accessed 2019-03-29.

- Rogers, Raymond R.; Carl C. Swisher III; Paul C. Sereno; Alfredo M. Monetta; Catherine A. Forster, and Ricardo N. Martínez. 1993. The Ischigualasto Tetrapod Assemblage (Late Triassic, Argentina) and 40Ar/39Ar Dating of Dinosaur Origins. Science 260. 794–797. Accessed 2019-03-29.

- Cabrera, Ángel. 1943. El primer hallazgo de terápsidos en la Argentina. Notas del Museo de la Plata 8. 317–331.

Books

- Langer, Max C.; Sterling J. Nesbitt; Jonathas S. Bittencourt, and Randall B. Irmis. 2013. Anatomy, phylogeny and palaeobiology of early archosaurs and their kin. Geological Society, London, Special Publications 379. 157–186.

- Weishampel, David B.; Peter Dodson, and Halszka Osmólska (eds.). 2004. The Dinosauria, 2nd edition, 1–880. Berkeley: University of California Press. Accessed 2019-02-21.ISBN 0-520-24209-2

Further reading

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ischigualasto Formation. |

- F. Abdala. 2000. Catalogue of non-mammalian cynodonts in the Vertebrate Paleontology Collection of the Instituto Miguel Lillo, Universidad Nacional de Tucuman, with comments on species. Ameghiniana 37(4):463-475

- P. C. Sereno, C. A. Forster, R. R. Rogers and A. M. Monetta. 1993. Primitive dinosaur skeleton from Argentina and the early evolution of Dinosauria. Nature 361:64-66

- F. E. Novas. 1986. Un probable teropodo (Saurischia) de la Formacion Ischigualasto (Triasico Superior), San Juan, Argentina [A probable theropod (Saurischia) from the Ischigualasto Formation (Upper Triassic), San Juan, Argentina]. IV Congreso Argentino de Paleontologia y Bioestratigrafia 1:1-6

- V.H. Contreras. 1981. Datos preliminares sobre un nuevo rincosaurio (Reptilia, Rhynchosauria) del Triasico Superior de Argentina. Anais II Congresso Latino-Americano Paleontologia, Porto Alegre 2:289-294

- Bonaparte, J.F. 1978. El Mesozóico de América de Sur y sus Tetrapodos - The Mesozoic of South America and its tetrapods. Opera Lilloana 26. 1–596.

- R. M. Casamiquela. 1967. Un nuevo dinosaurio ornitisquio triasico (Pisanosaurus mertii; Ornithopoda) de la Formación Ischigualasto, Argentina [A new Triassic ornithischian dinosaur (Pisanosaurus mertii; Ornithopoda) from the Ischigualasto Formation, Argentina]. Ameghiniana 4(2):47-64

- C. B. Cox. 1965. New Triassic dicynodonts from South America, their origins and relationships. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, Series B 248(753):457-516

- O. A. Reig. 1963. La presencia de dinosaurios saurisquios en los "Estratos de Ischigualasto" (Mesotriasico Superior) de las provincias de San Juan y La Rioja (República Argentina) [The presence of saurischian dinosaurs in the "Ischigualasto beds" (upper Middle Triassic) of San Juan and La Rioja Provinces (Argentine Republic)]. Ameghiniana 3(1):3-20