James Craig, 1st Viscount Craigavon

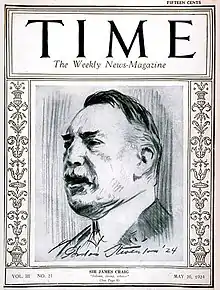

James Craig, 1st Viscount Craigavon PC PC (NI) DL (8 January 1871 – 24 November 1940), was a prominent Irish unionist politician, leader of the Ulster Unionist Party and the first Prime Minister of Northern Ireland. He was created a baronet in 1918 and raised to the Peerage in 1927.

The Viscount Craigavon | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1st Prime Minister of Northern Ireland | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 7 June 1921 – 24 November 1940 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Monarch | George V (1922–1936) Edward VIII (1936) George VI (1936–1940) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Governor | The Duke of Abercorn | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Office established | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | John Miller Andrews | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Leader of the Ulster Unionist Party | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 7 June 1921 – 24 November 1940 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Sir Edward Carson | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | John Miller Andrews | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal details | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | 8 January 1871 Belfast, Ireland | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 24 November 1940 (aged 69) Glencraig, Northern Ireland | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nationality | British | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Political party | Ulster Unionist Party | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Spouse(s) | Cecil Mary Tupper | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Children | 3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Education | Merchiston | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Military service | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Allegiance | United Kingdom | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Branch/service | British Army | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Years of service | 1899–1901 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rank | Captain | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Unit | 3rd (Militia) Royal Irish Rifles | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Battles/wars | Second Boer War | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Early life

Craig was born at Sydenham, Belfast, the son of James Craig (1828–1900), a wealthy whiskey distiller who had entered the firm of Dunville & Co as a clerk: by age 40 he was a millionaire and a partner in the firm. James Craig Snr. owned a large house called Craigavon, overlooking Belfast Lough. His mother, Eleanor Gilmore Browne, was the daughter of Robert Browne, a prosperous man who owned property in Belfast and a farm outside Lisburn. Craig was the seventh child and sixth son in the family; there were eight sons and one daughter in all. [1]

He was educated at Merchiston Castle School in Edinburgh, Scotland; his father had taken a conscious decision not to send his sons to any of the more fashionable public schools. After school he began work as a stockbroker, eventually opening his own firm in Belfast.

Military career

Craig enlisted in the 3rd (Militia) battalion of the Royal Irish Rifles on 17 January 1900 to serve in the Second Boer War. He was seconded to the Imperial Yeomanry, a cavalry force created for service during the war, as a lieutenant in the 13th battalion on 24 February 1900,[2][3] and left Liverpool for South Africa on the SS Cymric in March 1900.[4] After arrival he was soon sent to the front, and was taken prisoner in May 1900, but released by the Boers because of a perforated eardrum. On his recovery he became deputy assistant director of the Imperial Military Railways, showing the qualities of organisation that were to mark his involvement in both British and Ulster politics. In June 1901 he was sent home suffering from dysentery, and by the time he was fit for service again the war was over. He was promoted to captain in the 3rd Royal Irish Rifles on 20 September 1902,[5] while still seconded to South Africa.

Military life suited him well, but he became impatient with what he saw as the lack of professionalism and efficiency in the British Army.

Politics

On his return to Ireland, having received a £100,000 legacy from his father's will, he turned to politics, serving as Member of the British Parliament for East Down from 1906 to 1918. From 1918 to 1921 he represented Mid Down, and served in the British government as Parliamentary Secretary to the Minister for Pensions (1919–20) and Parliamentary Secretary to the Admiralty (1920–21).

Craig rallied Ulster loyalist opposition to Irish Home Rule in Ulster before the First World War, organising the paramilitary Ulster Volunteers (UVF) and buying arms from Imperial Germany. The UVF became the nucleus of the 36th (Ulster) Division during the First World War. He succeeded Edward Carson as leader of the Ulster Unionist Party in February 1921.

In the 1921 Northern Ireland general election, the first ever, he was elected to the newly created Northern Ireland House of Commons as one of the members for County Down.

On 7 June 1921, Craig was appointed the first Prime Minister of Northern Ireland by the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland.[6] The House of Commons of Northern Ireland assembled for the first time later that day.[7] A dedicated member of the Orange Order and staunchly Protestant,[8] he famously stated, in April 1934, in response to George Leeke's question regarding Craig's Protestant Parliament:

The hon. Member must remember that in the South they boasted of a Catholic State. They still boast of Southern Ireland being a Catholic State. All I boast of is that we are a Protestant Parliament and a Protestant State. It would be rather interesting for historians of the future to compare a Catholic State launched in the South with a Protestant State launched in the North and to see which gets on the better and prospers the more. It is most interesting for me at the moment to watch how they are progressing. I am doing my best always to top the bill and to be ahead of the South.[9]

This speech is often misquoted, intentionally or otherwise, as: "A Protestant Parliament for a Protestant People", and conflated with an incident which occurred respective to the naming of the New City of Craigavon. Knockmena (a corruption of the townland name, Knockmenagh) was the preferred name nationalists hoped would be used, and which might have attracted broad acceptance on both sides. On 6 July 1965, it was announced that the new city would be named Craigavon after Craig. A noted nationalist, Joseph Connellan, interrupted the announcement with the comment, "A Protestant city for a Protestant people".[10]

Later that year, speaking in the House of Commons at Stormont on 21 November 1934 in response to an accusation that all government appointments in Northern Ireland were carried out on a religious basis, he replied: "... it is undoubtedly our duty and our privilege, and always will be, to see that those appointed by us possess the most unimpeachable loyalty to the King and Constitution. That is my whole object in carrying on a Protestant Government for a Protestant people. I repeat it in this House".[11]

He was made a baronet in 1918, and in 1927 was created Viscount Craigavon, of Stormont in the County of Down. He was also the recipient of honorary degrees from The Queen's University of Belfast (1922) and Oxford University (1926).

Craig had made his career in British as well as Northern Irish politics; but his premiership showed little sign of his earlier close acquaintance with the British political world. He became intensely parochial, and suffered from his loss of intimacy with British politicians in 1938, when the British government concluded agreements with Dublin to end the Anglo-Irish economic war between the two countries. He never tried to persuade Westminster to protect Northern Ireland's industries, especially the linen industry, which was central to its economy. He was anxious not to provoke Westminster, given the precarious state of Northern Ireland's position. In April 1939, and again in May 1940 in the Second World War, he called for conscription to be introduced in Northern Ireland (which the British government, fearing a backlash from nationalists, refused).[12] He also called for Churchill to invade Éire, the south of Ireland, using Scottish and Welsh troops in order to seize the valuable ports and install a Governor-General at Dublin.[13] Lady Londonderry confided to Sir Samuel Hoare, the Home Secretary until the outbreak of the war, that Craigavon had become "ga-ga"[14] but Craigavon was still prime minister when he died peacefully at his home at Glencraig, County Down at the age of 69. He was buried on the Stormont Estate, and was succeeded as the Prime Minister of Northern Ireland by the Minister of Finance, John Miller Andrews.

Personal life

His wife, Cecil Mary Nowell Dering Tupper (Viscountess Craigavon), whom he married on 22 March 1905 after a very brief courtship, was English, the daughter of Sir Daniel Tupper, assistant comptroller of the Lord Chamberlain's department of the king's household. They had twin sons and a daughter. A president of the Ulster Women's Unionist Council, she was created a Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire in 1941.[15]

Cecil Mary Nowell Dering Tupper was a fourth cousin of the Queen Mother, Elizabeth Angela Marguerite Bowes-Lyon.

- John Lyon, IX Earl of Strathmore, m. 24 February 1767, Mary Eleanor Bowes.

- Col. Barrington Price, m. 1 May 1789, Lady Mary Bowes-Lyon.

- Rev. Cholmeley Edward John Dering, m. 1817, Maria Price.

- Lt.-Col. Cholmeley Edward Dering, m. 1841, Cecilia Elizabeth Louisa Chadwick.

- Sir Daniel Alfred Anley Tupper, m. 1882, Mary Cholmeley Dering.

- Cecil Mary Nowell Dering Tupper, m. 22 March 1905. James Craig, I Viscount Craigavon.

Craigavon was succeeded as second viscount by his elder son, James (1906–1974). His estate was valued at £3,228, 2s., 6d. effects in England: probate, 20 March 1941, CGPLA NIre., £24, 138 9s. 9d.: probate, 3 March 1941, CGPLA NIre.

Craig had a keen interest in Ulster Agriculture and was Vice-President of Listooder and District Ploughing Society (the oldest in Ireland) from November 1906 until November 1921 and continued to present the all-Ireland cup class until 1926.[16]

Arms

|

Motto:

|

See also

- Belfast Blitz

- The Emergency

- List of Northern Ireland Members of the House of Lords

- Craigavon – The 'New Town' named after Craig

Notes

- Patrick Buckland (1980). James Craig: Lord Craigavon. Gill and Macmillan. p. 3.

- "No. 27168". The London Gazette. 23 February 1900. p. 1256.

- "No. 27171". The London Gazette. 6 March 1900. p. 1528.

- "The War - Embarcation of Troops". The Times (36078). London. 1 March 1900. p. 7.

- "No. 27475". The London Gazette. 19 September 1902. p. 6024.

- "Belfast Gazette" (1). 7 June 1921. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "NI Hansard HC vol.1 cc.1–10". Stormont Papers. 7 June 1921. Retrieved 23 April 2019.

- CAIN website, cain.ulst.ac.uk; accessed 4 September 2017.

- Northern Ireland House of Commons Official Report, Vol 34 col 1095. Sir James Craig, Unionist Party, then Prime Minister of Northern Ireland, 24 April 1934. This speech is often misquoted as: "A Protestant Parliament for a Protestant People", or "A Protestant State for a Protestant People".

- Mulholland, Marc. "Why Did Unionists Discriminate?, academia.edu; accessed 4 September 2017.

- Northern Ireland Parliamentary Debates; Vol. 17, columns 73 & 74; accessed 4 September 2017.

- Fisk, Robert (1983). In time of war: Ireland, Ulster, and the price of neutrality, 1939–45. London: André Deutsch. p. 158. ISBN 978-0-233-97514-6.

- "Churchill was asked to invade 'Nazi' Ireland during Second World War". 21 March 2010.

- Jonathan Bardon. "Extracts from an article, "The Belfast Blitz, 1941"". BELFAST BLITZ. Retrieved 19 January 2015.

- "Clarence 10". www.william1.co.uk.

- Callum Bowsie (31 January 2021). "History of the oldest ploughing society in Ireland - Listooder & Dist" (Farming Life). Newsletter. pp. 47–49.

References

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to James Craig, 1st Viscount Craigavon. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: James Craig, 1st Viscount Craigavon |

- Hansard 1803–2005: contributions in Parliament by the Viscount Craigavon

- "Archival material relating to James Craig, 1st Viscount Craigavon". UK National Archives.

- . . Dublin: Alexander Thom and Son Ltd. 1923. p. – via Wikisource.