Jean Victor de Constant Rebecque

Jean Victor baron de Constant Rebecque (22 September 1773 – 12 June 1850) was a Swiss lieutenant-general in Dutch service of French ancestry. As chief-of-staff of the Netherlands Mobile Army he countermanded the order of the Duke of Wellington to evacuate Dutch troops from Quatre Bras on the eve of the Battle of Quatre Bras, thereby preventing Marshal Michel Ney from occupying that strategic crossroads.

Jean Victor de Constant Rebecque | |

|---|---|

Jean Victor de Constant Rebecque by Jan Baptist van der Hulst | |

| Born | 22 September 1773 Genève, Republic of Geneva |

| Died | 12 June 1850 (aged 76) Schönfeld, Austrian Silesia |

| Allegiance | United Kingdom of the Netherlands |

| Service/ | General Staff |

| Years of service | 1788–1837 |

| Rank | lieutenant-general |

| Unit | Netherlands Mobile Army |

| Battles/wars | Peninsular War Battle of Waterloo Belgian Revolution Ten Days Campaign |

| Awards | Knight Commander Military William Order |

Biography

Family Life

Rebecque was the son of François Marie Samuël de Constant d'Hermenches, seigneur d'Hermenches (1729–1800) and his second wife Louise Cathérine Gallatin (1736–1814). The father was, like the grandfather Samuel Constant de Rebecque (1676–1782) (who reached the rank of lieutenant-general), a Swiss officer in the service of the Dutch Republic. A nephew (not a brother as sometimes erroneously stated) was Benjamin Constant. Jean Victor de Constant Rebecque married Isabella Catharina Anna Jacoba baroness van Lynden (1768–1836) in Braunschweig on 29 April 1798.[1]

They had children:

- Victor, Baron of Constant Rebecque

- Charles de Constant Rebecque

- Guillaume de Constant Rebecque

- Louise de Constant Rebecque

Early career

Rebecque entered the service of France as a sous-lieutenant in a regiment of Swiss Guards in 1788. He started a journal that year that he faithfully kept every day of the rest of his life, thereby providing useful source material to historians. On 10 August 1792 his regiment was massacred at the Tuileries Palace by French revolutionaries, but he escaped with his life.[2] He returned to Switzerland where he was in military service until he (like his ancestors before him) entered the service of the Dutch Republic in 1793 in the regiment of Prince Frederick (a younger son of stadtholder William V, Prince of Orange). After the fall of the Republic, and the proclamation of the Batavian Republic he first entered British service (1795–1798) and subsequently Prussian service (1798–1811). During that Prussian service from 1805 he tutored the future William II of the Netherlands in military science and helped him pass his exams as a Prussian officer. When William started his studies at Oxford University he accompanied the young prince there and obtained a doctorate honoris causa from Oxford himself in 1811.[3]

William was next appointed aide-de-camp of the Duke of Wellington during the Peninsular War and Rebecque likewise entered British service again on 12 May 1811 as a major, and participated in every battle the Duke (and William) fought there, distinguishing himself at the Battle of Vittoria.[3]

When William, and his father William I of the Netherlands, returned to the Netherlands in November 1813, Rebecque was appointed a lieutenant-colonel in the Orange-Nassau Legion. He advanced very rapidly after that: colonel and aide-de-camp of the Sovereign Prince on 31 December 1813, and Quarter-master-general on 15 January 1814. He took part in the Siege of Bergen op Zoom (1814), and then was promoted to major-general on 30 November 1814.[3]

Rebecque played a very prominent role in the organization from scratch of the armed forces of the Kingdom of the United Netherlands in 1813–1815. On 11 April 1814 he was appointed chief-of-staff of the new Netherlands Mobile Army that was then formed to besiege the French in Antwerp. In July 1814 he was appointed in a commission that was charged with the formation of a combined Dutch-Belgian army. He played a leading role in that commission. Next he helped Prince Frederick of the Netherlands found the headquarters of the Netherlands Mobile Army, that was to play such an important part in the Waterloo Campaign, on 9 April 1815.[3]

Probably because many Dutch officers (like generals Chassé and Trip) had served in the French Grande Armée this new army was organized along the lines of the French army. In any case its general staff took Marshal Berthier's famous état-major-général as a model, and not the British system. Nevertheless, because Rebecque had long served as a staff officer in Wellington's army, he was well acquainted with British procedures, and knew his opposite numbers personally.

Quatre Bras and Waterloo

After Napoleon Bonaparte escaped from Elba and quickly overthrew the restored Bourbon monarchy in March 1815, he quickly formed Army of the North, with the help of veterans like François Aimé Mellinet (who organized the Jeune Garde), though he had to do without Marshals Berthier and Murat for various reasons. Threatened by this military build-up the Great Powers declared war on Napoleon personally and started to prepare for the inevitable showdown. The Sovereign Prince of the Netherlands also brought his plans for forming his Kingdom of the United Netherlands forward and proclaimed himself king on 16 March 1815 (see Eight Articles of London). Incidentally, this allowed him to give up his title of Prince of Orange and bestow it upon his eldest son as a courtesy title. That eldest son was now also put in charge of the new Netherlands Mobile Army, though at the same time the Duke of Wellington was appointed a field-marshal in the Dutch army. The arrangement was to be that Wellington would command the combined Anglo-allied army that was now assembling in the "Belgian" part of the United Netherlands, but that the Prince of Orange would be in charge of the Belgian-Dutch troops (with his younger brother Frederick nominally commanding a corps). Only Wellington and his chief-of-staff Lord Hill would be able to give direct orders to the Belgian/Dutch troops, but in practice Wellington always went "through channels" and conveyed his orders to the Belgian/Dutch units via the Prince of Orange.

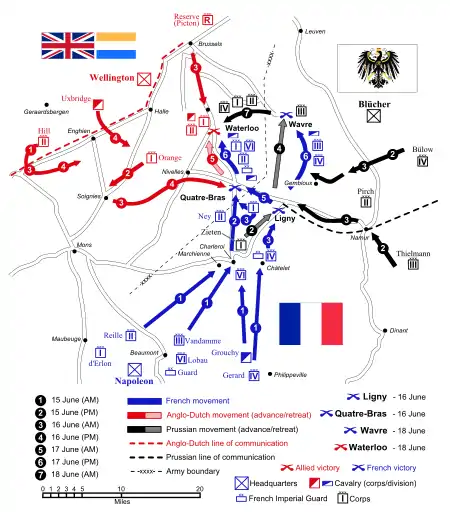

Beside the Anglo-allied army there also was still a Prussian army under field-marshal Prince Blücher in the Belgian Netherlands, as this part of the country formally still was a Coalition military governorate-general (with king William as its governor-general). The two armies were cantoned over a wide area, with the Prussians taking the south-eastern part, and the Anglo-allies the north-western part. Napoleon strategy was to exploit the dispersal of the two encamped armies by thrusting his Army of the North into the demarcation line between the two armies and by moving quickly to defeat each army in turn (as his Army of the North was larger than each of the Coalition armies separately). For this to succeed he needed the element of surprise, because if the Coalition allies would have known his exact intentions, and would have been able to react in time, they could of course have combined their armies in time and blocked his purpose.

Beside the element of surprise the geo-strategical shape of the theatre of war was also important. The terrain in south-eastern Belgium, where the hilly Ardennes are located, makes only a few invasion routes feasible. Besides, the number of highways was limited in 1815, and this further limited the movements of the opposing armies. Belgium has always been an important theatre of war in the course of the centuries, but in 1815 it had been peaceful since the victory of the French revolutionary armies in 1794, and most generals involved had last campaigned in the country when they were young officers, if at all. Strategic information was therefore at a premium.

Wellington himself had traversed the country on his way to Paris in 1814 and he had at that occasion scouted the area around Waterloo and was aware of its advantages as a battlefield in case Brussels was to be defended. He also commissioned one of his staff officers to survey the area and to assess its strategic choke points. One of those points was the crossroads of the Charleroi-Brussels road and the Nivelles-Namur road at Quatre Bras. It was generally recognized that the first road would be the prime venue for the French to reach Brussels, and the second one was indispensable for maintaining communications between the two Coalition armies. For that reason occupying the crossroads was essential; whichever army controlled it would have a decisive strategic advantage. For that reason Rebecque, as chief-of-staff of the Netherlands army ordered the commander of the Netherlands 2nd division, De Perponcher to secure it at all times on 6 May 1815.[3]

However, Napoleon achieved his strategic surprise, because of a certain reticence on the part of the Coalition allies: the Prussians and British had not declared war on France, just on Napoleon personally (a subtle, but important difference) and they, therefore, refrained from conducting cavalry reconnaissances across the French border. The Netherlands cavalry was not so constrained, and did reconnoitre the border area, but the three Netherlands cavalry brigades were too thin on the ground to cover the area thoroughly. When Napoleon, therefore, started his lightning offensive, this was not discovered before it was almost too late. He was already in Charleroi before the French were discovered and when news of this sudden appearance reached Wellington he still worried that this was just a feint, and that the true advance would come by way of Mons. Because of this possibility of being outflanked, and being cut off from the escape route to the coast, Wellington on the evening of 15 June decided to concentrate his army around Nivelles. His orders went out to all British troops directly, and to the Netherlands troops through the intermediary of the Prince of Orange and his staff (as described above).

These orders to the 2nd Brigade, 2nd Netherlands Division under major-general Prince Bernhard of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach, at Quatre Bras at the time, would have evacuated this essential strategic point. As Saxe-Weimar was aware of the oncoming French because he heard firing from the vicinity of Frasnes, and saw the alarm beacons lighted, the order to evacuate surprised him. He alerted the divisional commander, De Perponcher, who immediately put the other brigade of his division (then at Nivelles) on alert, and sent a staff officer, captain De Gargen, to the Netherlands headquarters at Braine-le-Comte.[4]

Here, Rebecque (on the strength of De Gargen's report), in consultation with De Perponcher, decided to countermand Wellington's order, and instead ordered De Perponcher to reinforce Saxe-Weimar immediately with the 1st Brigade, 2nd Netherlands Division, under major-general Willem Frederik van Bylandt. He immediately reported this decision to the Prince of Orange in Brussels, who informed Wellington of it at the famous ball of the Duchess of Richmond.[4][5] A lesser man might have just sent a suggestion to Wellington, meanwhile letting the order stand. Wellington was not known for looking kindly upon having his orders disregarded, let alone countermanded,[lower-alpha 1] as Rebecque must have been well aware, as one of Wellington's former staff officers. He therefore displayed that rare commodity: moral courage.

The decision was not a minor one. Rebecque probably made it to keep communications with Blücher open, which may not have been the first thing on Wellington's mind. In any case, in the event Wellington did not come to Blücher's aid at the Battle of Ligny. But the strategic importance of Quatre Bras did not only hinge on the Nivelles-Namur road. Probably even more important was the Charleroi-Brussels road for Napoleon's political objective: the speedy occupation of Brussels. Had Marshal Michel Ney succeeded in occupying the crossroads and the road to the north, as Napoleon intended, the way would have been wide open for the French to quickly march north after their victory at Ligny; Brussels would probably have fallen, without Wellington being able to do anything about it; and with the fall of Brussels king William's little project of the Kingdom of the United Netherlands would have failed and his budding country might have been pushed out of the war. In any case, there probably would not have been a battle of Waterloo.[lower-alpha 2]

As it was, Ney was frustrated by the far-outnumbered Netherlands troops; Wellington won the Battle of Quatre Bras; the Anglo-allied was able to make a strategic withdrawal to Wellington's preferred battleground near Waterloo. Rebecque of course was also present at that battle as a staff officer, busily oiling the wheels of command and occasionally playing a decisive command role himself, as when he helped rally the broken Dutch militia battalions of Bijlandt's Brigade when they retreated to the position of the steadfast 5th Militia Battalion, which sustained such heavy casualties at Waterloo, only to be maligned by later historians. For his gallantry Rebecque was made a Knight Commander in the Military William Order on 8 July 1815.

Belgian Revolution and Ten Days Campaign

After the Netherlands Mobile Army returned from the campaign in France in 1816, Rebecque was confirmed as Chief of the General Staff of the Netherlands army (which he would remain until his retirement). As such he capably organised that army and the system of conscription on which it was based in close cooperation with Prince Frederick.[6] He was promoted to lieutenant-general in 1816. In 1826 he was appointed gouverneur (tutor) of the young sons of the Prince of Orange, like he had been the tutor of their father from 1805.[7] When in 1830 king William was asked to act as arbiter in the matter of the conflict over the delineation of the Maine and New Brunswick border, the Northeastern Boundary Dispute (a matter that was only finally settled by the Webster-Ashburton Treaty in 1842,[8] Rebecque headed the fact-finding commission that prepared the arbitrage award.[7]

This award was made in August 1830 just about when the Belgian Revolution erupted in which Rebecque was to play a controversial role. From hindsight the experiment of reuniting the Habsburg Netherlands in the guise of the Kingdom of the United Netherlands probably was never a good idea. Since the separation of the Dutch and Belgian provinces in 1579 (when the Union of Arras and the Union of Utrecht were concluded) the two countries had grown even further apart than they were already, with Belgium becoming more monolithically Catholic due to the enforced exodus of Protestants to the North. The last time reunification was seriously discussed was during the abortive peace talks between the Brussels and The Hague States-Generals after the conquest of Maastricht by stadtholder Frederick Henry, Prince of Orange in 1632.[9] After that Amsterdam opposition to the opening of the Scheldt for trade on Antwerp made the Dutch very reluctant to even consider reunification. They were satisfied with a quasi-codominion with the Austrians over their southern neighbors after 1715. That is where matters stood until in 1790 the United States of Belgium briefly explored accession to the Dutch Republic, but nothing came of that.

The only one who was truly enthusiastic about the 1815 reunion was King William. Both his southern and northern subjects were sceptical, but at first acquiescent. From hindsight much has been made of alleged preferential treatment of Dutchmen by the government as a cause of the rupture in 1830, but close scrutiny of the actual history of the union probably would not uphold that assertion: William was even-handed in his language policy, trying to give equal weight to both French and Dutch as government languages. This meant that in Belgium Flemish was formally emancipated from the previously dominant French, but in actual practice French continued to dominate. It was the language of the educated elite. As a matter of fact, the aristocratic First Chamber of the States-General conducted its business exclusively in French, because the Belgian members pleaded ignorance of Dutch. Many of the government elite were consequently "frenchified", even the ones that were of Dutch extraction, so the complaint of giving preference to French speakers was voiced at least as loudly as the opposite complaint.

An example is the Prince of Orange: though he may have acquired Dutch in his later life, his first language was undoubtedly French. This also applied to his forebears (though this may come as a shock to many Dutchmen): the language of the court of the House of Orange, and of Orange-Nassau, had always been French (and would remain so until the early 20th century, long after the split with Belgium). Rebecque certainly never became proficient in Dutch, and there is no reason why he should have: his brother officers always spoke French (bar a few Englishmen, possibly) and contacts with Dutch speakers could always be mediated by bilingual subalterns and servants. This applied to many of the Netherlands officers who had served at Quatre Bras and Waterloo, and in 1830 still occupied the upper ranks of the Netherlands army.

To this fully assimilated elite the Brussels insurrection of August 1830, with its anti-Dutch overtones therefore came as a rude shock. At first they reacted with indecision and with reluctance to apply military severity. Especially the Prince of Orange had the illusion that he could rely on his undoubted popularity (he was far more liberal than his paternalistic father, and for that reason hardly on speaking terms with the king) and might be able to reason with the insurrectionists. However, the échec of Orange's brave entry into the hostile city on 1 September with only a few companions (of which Rebecque was one), which almost ended in a lynching, put an end to that. Rebecque (who was the political antipode of his liberal nephew Benjamin Constant, probably because of his traumatic experience in the Tuileries in 1792) now counseled playing the military card. He is credited with (or blamed for) having made the plan for the assault on Brussels on 21 September, which ended catastrophically, and caused much bloodshed. Rebecque himself was wounded in the street fighting. The Dutch army retreated to Antwerp where the next catastrophe, the indefensible bombardment of the city by general Chassé, happened.[10]

Rebecque was back the next year, when he helped organise the ill-fated Ten Days Campaign. This attempt to retrieve terrain lost, was executed brilliantly in a military sense, but politically it was a disaster. One wonders what Rebecque and his political masters hoped to achieve, even if the French had not intervened? They could easily beat the nascent Belgian army, but what would have been next? It seems unlikely that the Dutch would have had the stomach for the kind of repression that Russia used to quell the Polish Insurrection of 1830–1831. As White makes clear, the real objective may more properly have been to strengthen the Dutch position in the following negotiations, which the Dutch successes arguably did. But a reunification of the two countries, as king William seems to have hoped for, was never in the cards.[11]

One small detail of the Campaign involved Rebecque posthumously. The armistice was signed on 12 August 1832 but shortly afterwards a young Belgian artillery officer, Alexis-Michel Eenens thought he saw a Dutch violation of the ceasefire and opened fire on the Dutch troops. This minor incident got a peculiar follow-up when Eenens (by then a lieutenant-general and military historian), published Documents historiques sur l'origine du royaume de Belgique. Les conspirations militaires de 1831 (Bruxelles, 1875, 2 vols.) in 1875. This work caused a furore, because Eenens accused a number of prominent Belgians of treason in the course of the Revolution. And he also raked up the old alleged ceasefire violation, accusing the Prince of Orange of culpability. All of this caused a heated polemic with a number of Dutch generals and historians. A grandson of Rebecque published an extract of Rebecque's journal as Constant Rebecque, J.D.C.C.W. de (1875) Le prince d'Orange et son chef d'état-major pendant la journée du 12 août 1831, d'après des documents inédits, in an attempt to contradict Eenens' accusations.

Rebecque retired from the service in 1837. He was made a Dutch baron on 25 August 1846 by his old protégé, now king William II. He retired to his estates in Silesia and died there in 1850, almost 77 years old.[7]

Notes

- General Karl Freiherr von Müffling, the Prussian liaison officer at Wellington's headquarters recounts an anecdote where two commanders of cavalry brigades at Waterloo, Vivian and Vandeleur, were so scared of disobeying Wellington's order not to move, that they refused to come to the aid of Ponsonby's troopers when those were slaughtered at Waterloo (Müffling 1853, pp. 245, ff).

- See for an appreciation of the importance of the actions of Rebecque and Perponcher before the Battle of Quatre Bras see Bas & T'Serclaes 1908, pp. 440–444

Citations

- Recueil historique, généalogique, chronologique et nobiliaire des maisons et ...

- Tornare 2003, p. 511.

- Tornare 2003, p. 512.

- Hamilton-Williams 1993, p. 177.

- Bas & T'Serclaes 1908, pp. 395–411.

- White 1835, p. 133.

- Nationaal Archief.

- Hyde 1922, pp. 116–117.

- Israel 1995, pp. 515–523.

- White 1835, pp. 221 ff, 337–359.

- White 1835, pp. 324–325.

References

- Bas, François de; T'Serclaes, Jacques Augustin Joseph Alphonse Regnier Laurent Ghislain T'Serclaes de Wommerson (comte de) (1908), La campagne de 1815 aux Pays-Bas d'après les rapports officiels néerlandais (in Dutch), 1, A. Dewit, p. 395–411

- Hamilton-Williams, D (1993), Waterloo. New Perspectives. The Great Battle Reappraised, John Wiley & Sons, p. 177, ISBN 0-471-05225-6

- Müffling, K.F. von (1853), Passages from My Life: Together with Memoirs of the Campaign of 1813 and 1814, pp. M1 245 ff

- Hyde, C.H. (1922), International Law Chiefly as Interpreted and Applied by the United States, pp. 116–117

- Israel, Jonathan J. (1995), The Dutch Republic: Its Rise, Greatness and Fall, 1477–1806, Oxford University Press, pp. 515–523, ISBN 0-19-873072-1

- Nationaal Archief, Jean Victor baron de Constant Rebecque (1773–1850) (in Dutch)

- Tornare, A.-J. (2003), Les Vaudois de Napoléon: des Pyramides à Waterloo 1798–1815 (in French) (Cabedita ed.), pp. 511–512, ISBN 9782882953810

- White, C (1835), The Belgic revolution of 1830

Further reading

- Bas, F. de (1908–1909), La campagne de 1815 aux Pays-Bas d'après les rapports officiels néerlandais (in French), 1 (volume 1 Quatre Bras; Vol. 2 Waterloo ed.)