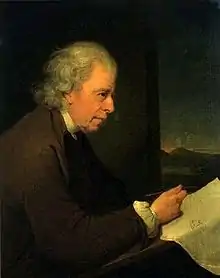

John Whitehurst

John Whitehurst FRS (10 April 1713 – 18 February 1788), born in Cheshire, England, was a clockmaker and scientist, and made significant early contributions to geology. He was an influential member of the Lunar Society.

Life and work

Whitehurst was born in Congleton, Cheshire, to a clockmaker, the elder John Whitehurst.[1] Receiving only a slight formal education, the younger Whitehurst was taught clockmaking by his father, who also encouraged the boy's pursuit of knowledge. In 1734, at the age of twenty-one, Whitehurst visited Dublin to inspect a clock of curious construction of which he had heard.

Career

About 1736, Whitehurst entered into business for himself at Derby, where he soon obtained great employment, distinguishing himself by constructing several ingenious pieces of mechanism. Besides other works, he made the clock for the town hall, and on 6 September 1737, he was enrolled as a burgess in reward. He also made thermometers, barometers, and other philosophical instruments, and interested himself in contriving waterworks. He was consulted in almost every undertaking in Derbyshire and in the neighbouring counties in which skill in mechanics, pneumatics, and hydraulics was required.

In 1774, Whitehurst obtained a post at the Royal Mint in London. In 1775, on the passage of the act for the better regulation of the gold coinage, without any solicitation on his part, he was appointed stamper of the money-weights on the recommendation of the Duke of Newcastle.[3] Whitehurst moved to London, where he passed the rest of his life in scientific pursuits. other distinguished scientists visited his house in Colt Court, Fleet Street, formerly the abode of James Ferguson.

In 1772 - aged 59 years- he invented the "pulsation engine" (not to be mixed up with a Pulser pump), a water-raising device which was the precursor of the hydraulic ram.[4]

In 1778, Whitehurst published his theory on geological strata in An Inquiry into the Original State and Formation of the Earth. He had begun this while living at Derby, originally intending to facilitate the discovery of valuable minerals beneath the Earth's surface. He pursued his researches with so much ardour, that "the exposure he incurred" tended to impair his health.

On 13 May 1779, Whitehurst was elected a fellow of the Royal Society. In 1783, he was sent to examine the Giant's Causeway and the volcanic remains in the north of Ireland, embodying his observations in the second edition of his Inquiry.

About 1784 he contrived a system of ventilation for St. Thomas's Hospital.[5]

In 1787, age 74, a year before his death, he published An Attempt towards obtaining invariable Measures of Length, Capacity, and Weight, from the Mensuration of Time (London). Whitehurst wanted to study the shape of the earth by measuring differences in gravitation. For this, he studied heavy pendulums in different locations. He measured the length of the pendulum, the frequency of its oscillation and the length of the path its head was moving. He compared these to theoretical values he calculated assuming the globe is spherical. Starting on the assumption that the length of a second pendulum in the latitude of London was 39.2 inches, he deduced that the length of one oscillating 42 times a minute is 80 inches, while that of one oscillating twice as many times is 20 inches. The difference between these two lengths would therefore be exactly 5 feet. He found upon experiment that the actual difference was only 59.892 inches owing to the real length of the pendulum, oscillating once a second, being 39.125 inches. He obtained rough data, from which the true lengths of pendulums, the spaces through which heavy bodies fall in a given time, and many other particulars relating to the force of gravitation and the true figure of the earth could be deduced.

Personal life

On 9 January 1745, Whitehurst married Elizabeth Gretton, daughter of George Gretton, rector of Trusley and Dalbury in Derbyshire. In 1788 Whitehurst died, 75 years old, at his house in Bolt Court, Fleet Street, and was buried beside his wife in St. Andrew's burying-ground in Gray's Inn Road. There were no surviving children.

It has been suggested that Whitehurst is the model for Joseph Wright of Derby's picture of A Philosopher Lecturing on the Orrery in the Derby Museum and Art Gallery.[6]

Selected writings

- Whitehurst, John (1778). An Inquiry into the Original State and Formation of the Earth. London: J. Cooper. ISBN 0-405-10465-0. Archived from the original on 24 July 2011. Retrieved 24 July 2011. 2nd ed. (1786).

- Whitehurst, John (1787). An Attempt Towards Obtaining Invariable Measures of Length, Capacity, and Weight, From the Mensuration of Time, Independent of the Mechanical Operations Requisite to Ascertain the Center of Oscillation, or the True Length of Pendulums. London: W. Bent.

References

- Much of this article's content was adapted from the following source: . Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

- Labels in Derby Museum and Art Gallery, read August 2011

- "Industrial Revolution: A Documentary History". Adam Matthew Publications. Archived from the original on 27 March 2010. Retrieved 24 July 2011.

- Whitehurst, John (1775). "Account of a Machine for Raising Water, Executed at Oulton, in Cheshire, in 1772". Philosophical Transactions. 65: 277–279. doi:10.1098/rstl.1775.0026. JSTOR 106195.

- See Bernan's History and Art of Warming and Ventilation, 1845, ii. 70

- "Bygonederbyshire.co.uk 1700s: US patriot and his links to Derby". Retrieved 29 May 2011.

Further reading

- Craven, Maxwell (1996). John Whitehurst of Derby: Clockmaker and Scientist 1713–88. Derbyshire: Ashbourne. ISBN 0-9523270-3-1.

- Ford, Trevor D. (2002). "John Whitehurst (1713–1788): Philosopher, Geologist, Horologist and engineer". Geology Today. 18 (3): 100–107. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2451.2002.00342.x.

- Graciano, Andrew (2005). ""The Book of Nature is Open to All Men": Geology, Mining and History in Joseph Wright's Derbyshire Landscapes". The Huntington Library Quarterly. 68 (4): 583–600. doi:10.1525/hlq.2005.68.4.583.

- Graciano, Andrew (2008). Visualising the Unseen, Imagining the Unknown, Perfecting the Natural: Art and Science in the 18th and 19th Centuries. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84718-542-6.

- Hutton, C. (1792). The Works of John Whitehurst, F.R.S., with Memoirs of his Life and Writings. London: W. Bent. Retrieved 24 July 2011.

External links

- A Portrait of John Whitehurst

- An inquiry into the original state and formation of the earth (1778) - full digital facsimile at Linda Hall Library