Joseph O'Doherty

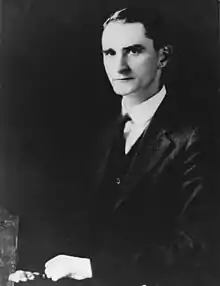

Joseph O'Doherty (24 December 1891 – 10 August 1979) was an Irish teacher, barrister, revolutionary, politician, county manager, member of the First Dáil and of the Irish Free State Seanad.[1]

Joseph O'Doherty | |

|---|---|

| |

| Teachta Dála | |

| In office January 1933 – July 1937 | |

| In office May 1921 – June 1927 | |

| Constituency | Donegal |

| In office December 1918 – May 1921 | |

| Constituency | Donegal North |

| Senator | |

| In office 1928–1934 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 24 December 1891 Derry, County Londonderry, Ireland |

| Died | 10 August 1979 (aged 87) |

| Resting place | Glasnevin Cemetery, Dublin, Ireland |

| Political party |

|

| Spouse(s) | Margaret (Mairéad) Irvine |

| Education | St Columb's College |

| Alma mater | |

| Military service | |

| Branch/service | |

Family

Joseph O'Doherty's father Michael O'Doherty was a prosperous entrepreneur from Gortyarrigan in the parish of Desertegney at the side of Raghin Beg mountain on the Inishowen peninsula, County Donegal. When he got married, Michael moved from Gortyarrigan to the town of Derry where he owned a hansom cab business and a chain of butcher shops, kept racing horses, traded in cattle, and supplied meat until 1916 for the British Royal Navy fort at Dunree.

Joseph's mother Rose O'Doherty (née McLaughlin 1860–?) inspired him to become a revolutionary. O'Doherty was born at his parents' home at 14 Little Diamond in the Bogside district of Derry on Christmas Eve 1891.[2][3] His brother, Séamus, was also a member of the IRB and took part in the events of the Easter Rising.[4]

Education

He was first educated at St Columb's College grammar school in Derry. He then studied at St Patrick's College, Drumcondra, (Dublin) where he qualified as a primary school teacher in 1912.

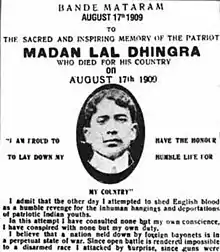

When he qualified as a teacher, Ireland was in the middle of the renewed expectations of Home Rule and the opposing activities of Sir Edward Carson, the leader of the Irish Unionist Alliance and of the Ulster Unionist Party. The young Joseph became well-soaked in revolutionary literature – partly through his interest in education which led him to read the articles and poetry of Pádraic Pearse – and he became a subscriber to the Indian revolutionary newspaper Bande Mataram.

By 1913/14, he was completely disillusioned with the Irish Parliamentary Party of John Redmond. With his teacher-training completed, O'Doherty taught for six months. He loved teaching and wanted to continue in this field, but was soon reluctantly persuaded by his elder brother Séamus O'Doherty to join the struggle for Irish freedom. He then joined the firm of Lawlor Ltd., of Ormonde Quay, Dublin, one of whose directors was Cathal Brugha, who subsequently became the first chairman and President of Dáil Éireann and the first Chief of Staff of the Irish Republican Army (the Old IRA).

He later studied at Trinity College Dublin and was enrolled at King's Inns where he qualified as a Barrister-at-Law.[5]

Rebellion

Irish Volunteers

In 1913 O'Doherty joined the Irish Volunteers (Óglaigh na hÉireann) when the organisation met at the Rotunda in Dublin. He was a member of the Volunteers 'B' Company, 3d Battalion, Dublin.

At the start of World War I, over 90% of the Irish Volunteers joined the National Volunteers and thus enlisted in the 10th (Irish) Division and 16th (Irish) Division of the British Army to fight in Europe. This left the Irish Volunteers with a rump estimated at 10–14,000 members.

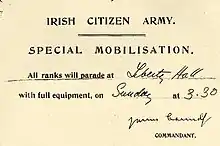

The Volunteers fought for Irish independence in 1916's Easter Rising, and were joined by the Irish Citizen Army, Cumann na mBan (The Irishwomen's Council) and Fianna Éireann to form the Irish Republican Army a.k.a. the Old IRA.

O'Doherty founded branches of the Volunteers from Crossmaglen to Malin Head. He was given command of the Derry Volunteers in the buildup to 1916 Easter Rising and remained a member of the Executive until 1921.

Irish Republican Brotherhood

Shortly after joining the Volunteers, Joseph's elder brother Seamus informed him of the existence of the secret revolutionary party called the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) of which he was a member. When Seamus asked Joseph for his opinion of secret organisations, Joseph replied that he thought secrecy was necessary to safeguard plans. Until then, he had no idea that the IRB existed and that his brother was a member. He was asked to join and was initiated into it by a close friend of the O'Doherty family, Seán Mac Diarmada (Seán MacDermott) who was the manager of the radical newspaper Irish Freedom. O'Doherty remained a member of the IRB until after the 1916 Easter Rising, and was specially mobilised by the IRB for the Howth Road and Killcoole gun-runnings.

Gun-running

In 1914, O'Doherty took part in the two audacious gun-running events at Howth and Kilcoole. The first landing took place on 26 July 1914 at Howth, when Erskine Childers and his wife Molly Childers smuggled 1,500 single-shot Mauser 71 rifles from Hamburg, Germany for the Irish Volunteers aboard their 51 ft gaff yacht, the Asgard. The guns, dating from the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71 were still functioning. They were later used in the attack on the General Post Office (GPO) in Dublin during the 1916 Easter Rising.

O'Doherty unloaded the first consignment of around 900 Mausers and 29,000 bullets off the Asgard along with Bulmer Hobson, Douglas Hyde, Darrell Figgis, Peadar Kearney, Thomas MacDonagh and others. This happened in public view in broad daylight and quickly led to police and military intervention. While accompanying the weapons convoy on the road from Howth to Dublin, O'Doherty broke the butt of his gun in a skirmish with the security forces, but successfully evaded them. As the King's Own Scottish Borderers infantry regiment returned to barracks, they were accosted at Bachelors Walk by civilians who threw stones and exchanged insults with the regulars. The soldiers bayoneted one man and shot into the unarmed crowd, resulting in four dead and 38 wounded civilians in what became known as the Bachelor's Walk massacre.

O'Doherty was also involved in the second gun-running the following week, around midnight on 1 August 1914, when the volunteers landed 600 more German-made Mauser 71 single-shot rifles and 20,000 rounds of ammunition off the Chotah at the much more discretely located beach at Kilkoole, Co. Wicklow, and spirited them away under cover of darkness. O'Doherty was in the lorry that delivered that consignment to a cache at St. Enda's School (which Padraic Pearse had founded in 1908) and which was now located at The Hermitage at Rathfarnam in the foothills of the Dublin Mountains where Pearse was waiting for them on the steps.

Other operations

In 1914 O'Doherty was one of a special group of IRB men mobilised under William Conway to frustrate a British Army recruiting meeting that was to be held at the Mansion House in Dublin. They were mobilised in Parnell Square with about 24 hours' rations and with arms, but the word came that a large group of British soldiers were in Dublin Castle and had taken over control of the area so that it would be impossible to get in, and the operation was called off.

In 1914, O'Doherty took part in a little-known operation in which the Irish Volunteers seized part of the 216 tonnes of guns and ammunition that had been delivered to the loyalist paramilitary Ulster Volunteer Force from the German Empire, in the Larne gun-running incident on 24 and 25 April of that year.

Soon afterwards, while attending a play at a theatre in Dublin with another member of the Volunteer Executive, O'Doherty was arrested in the lobby during the intermission. As they were about to be marched up to Dublin Castle, O'Doherty realised that they would both be tortured to reveal the location of the weapons caches and other information. Taking advantage of the soldiers being distracted by the crowd of onlookers who had gathered outside the theatre, O'Doherty ducked under the soldiers’ bayonets, leapt onto a passing tram, and escaped into the night. Days later, his friend's body was found, dismembered, at the Featherbed in the nearby Dublin mountains.

O'Doherty remained in Dublin until 1915 when his father asked him to return to Derry to manage the chain of butchers' shops business which he had recently bought there. After moving back to Derry, he joined the Derry branch of the Volunteers with Patrick McCartan who had previously edited the journal Irish Freedom in Pennsylvania, USA, and who was now in control of the IRB in the North. At McCartan's request in January 1916, O'Doherty took a delivery of arms via a trader named Edmiston & Scotts. The Derry Volunteer group also obtained quantities of .303 rifle ammunition which were delivered to Dublin, frequently by O'Doherty and members of his family.

1916 Easter Rising

O'Doherty was charged by the Irish Volunteers Executive to co-ordinate the Easter Rising in Derry, and to wait for the signal to begin the planned operation. But to his great dismay on Easter Sunday morning, the Sunday Independent newspaper published a last-minute countermanding order by the Volunteers Chief of Staff, Eoin MacNeill advising the Volunteers not to take part. Although the rising did take place in Dublin, the Derry Volunteers did not participate due to confusion over this countermanding order and a subsequent breakdown in communications with Dublin.

The rising took place mainly in Dublin where it caused considerable damage. Although volunteer groups also took action in Kerry, Cork, Wexford, Kildare, Donegal, and Galway, a considerable section of the Volunteers did not participate – partly as a result of MacNeill's cancellation.

A total of 3,430 men and 79 women were arrested. 187 were tried under a series of court-martials, and 90 were sentenced to death. 14 of them including all seven signatories of the Proclamation and were executed by firing squad at Kilmainham Gaol between 3 and 12 May. The most prominent leader to escape execution was the Commandant of the 3rd Battalion, Éamon de Valera, partly because of his American birth. He subsequently became President of the Irish Republic.

Capture and prison

O'Doherty and his brother Seamus were arrested a few days after the Easter Rising and taken in handcuffs to Dublin where they were imprisoned in Richmond Barracks in Dublin. O'Doherty was sent soon afterwards to the Abercorn Barracks at Ballykinlar in County Down. He spent time at Belfast gaol, Derry gaol, and was subsequently moved to Wakefield Prison in West Yorkshire (England), Wormwood Scrubs in London and the Frongoch internment camp in Wales, where he was sent as an Irish prisoner of war along with 1,800 others including Michael Collins and Arthur Griffith. Although he was not imprisoned in Mountjoy Gaol, he was one of the last people to speak to Pádraig Pearse (1879–1916) there (either as a visitor or through a window) before the latter was executed by firing squad.

In a filmed interview decades later, O'Doherty said "Those of us who were arrested were transferred in handcuffs to Richmond Barracks in Dublin, and subsequently transferred to England. Our crowd were marched between the files of a British regiment through the streets of Dublin, and several sections were stoned." [Quoted from a statement by him used (but not with his own voice) in the TG4 documentary film, "Internment Camp Frongoch" : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cgG-L8thLvM

Although the failure of the Rising was a major disappointment for the Volunteers, the Frongoch internment camp became known as the "University of Revolution", where the inmates planned their successful strategy to establish the First Dail in 1919. Among those interned there, 30 would become TDs (including O'Doherty, Richard Mulcahy, Michael Collins, Seán T. O'Kelly) and Éamon de Valera, two of whom later became Presidents of Ireland. After a few weeks, however, their prisoner of war status and privileges were withdrawn, and O'Doherty was released in early August 1916

O'Doherty went back to Derry and helped his father re-open the head office of his family business, and then in December he was contacted and asked to come up and manage the first republican paper that was published in 1916, called "The Phoenix".

German Plot

On the night of 16–17 May 1918, O'Doherty was arrested along with 150 Sinn Féin leaders concerning the so-called German Plot. This was disinformation campaign of black propaganda organised by the Dublin Castle administration to discredit Sinn Féin by falsely accusing it of conspiring with the German Empire to start an armed insurrection and invade in Ireland during World War I. This alleged conspiracy which would have diverted the British war effort, was used to justify the internment of Sinn Féin leaders, who were actively opposing attempts to introduce conscription in Ireland. O'Doherty was put in Arbour Hill gaol , but was released in 1917. He became a member of the executive of the Irish Volunteers that year.

Marriage

In 1918, O'Doherty married Margaret (Mairéad) Claire Susan Irvine (1893–1986), the same year she graduated as a medical doctor. She was born in Maguiresbridge, County Fermanagh. She studied medicine [where?] and after marrying O'Doherty, was appointed Chief Medical Officer of Derry, a post she occupied from 1919 to 1921, during the last year working without pay because she refused to take the Oath of Allegiance Oath of Allegiance (Ireland) to the English King George V.

Governance

1918 general election

In the aftermath of the Easter Rising of 1916, the Sinn Féin party (founded by Arthur Griffith in 1905), was reorganised and grew into a nation-wide movement, calling for abstention from Westminster and the establishment of a separate and independent Irish parliament. The party contested the 14 December 1918 general election, called following the dissolution of the British Parliament, and swept the country winning 73 of the 105 Irish seats.

O'Doherty, now aged 24, was elected as Sinn Féin Member of the UK Parliament for Donegal North, defeating his only opponent (from the Irish Parliamentary Party.[6] Acting on their pledge not to sit in the Westminster parliament, but instead to set up an Irish legislative assembly, 28 of the newly elected Sinn Féin representatives met and constituted themselves as the first Dáil Éireann. The remaining Sinn Féin representatives were either in prison or unable to attend for other reasons. The establishment of the First Dáil occurred on the same day as the outbreak of the Irish War of Independence (1919–1921) between the Irish Republican Army (the army of the Irish Republic known as the Old IRA) and the British security forces in Ireland. It was an escalation of the Irish revolutionary period into warfare.

First Dáil

The first Dáil met in the Round Room of the Mansion House in the heart of Dublin on 21 January 1919. The Dáil asserted the exclusive right of the elected representatives of the Irish people to legislate for the country. The Members present adopted a Provisional Constitution and approved the Declaration of Independence. The Dáil also approved a Democratic Programme, based on the 1916 Proclamation of the Irish Republic, and read and adopted a Message to the Free Nations of the World.

Following the simultaneous outbreak of the War of Independence in January 1919, the British Government decided to suppress the Dáil, and on 10 September 1919 Dáil Éireann was declared a dangerous association and was prohibited. Defying the law, however, the Dáil continued to meet in secret, and Ministers carried out their duties as best they could. In all, the Dáil held fourteen sittings in 1919. Of these, four were public and ten private. Three private sittings were held in 1920 and four in 1921.

O'Doherty was re-elected at the 1921 general election and opposed the Anglo-Irish Treaty which led to the partition of Ireland. In a Dáil meeting, he made the following statement:

"I know that the people in North Donegal at the present moment would accept this Treaty, and I think it is fair to the people of North Donegal that I should make that known; but they are accepting it under duress and at the point of the bayonet, and as a stop to terrible and immediate war. Like my co-Deputy from Tír Chonaill I came to this Session of Dáil Éireann with a mind that was open to conviction against these prejudices that I had; no argument that has been produced by those who are for this Treaty has made any influence on me; I see in it the giving away of the whole case of Irish independence; I am prepared to admit that the mandate I got from the constituents of North Donegal was one of self-determination; and it is a terrible thing and a terrible trial to have men in this Dáil interpreting that sacred principle here against the interests of the people. It is not peace they are getting; it is not the liberty they are getting which they are told they are getting, and they know it; and I will tell them honestly if I go to North Donegal again what they are getting."

He was subsequently re-elected as Anti-Treaty Sinn Féin and as an abstentionist republican in 1922 and 1923 respectively.

Civil War

.pdf.jpg.webp)

Following the signing of the Anglo-Irish Treaty, the Irish Civil War broke out between the pro-treaty Provisional Government led by Michael Collins (which became the Free State in December 1922) and the anti-treaty opposition (which was supported by O'Doherty) and which rejected the treaty as a betrayal of the Irish Republic (which had been proclaimed during the Easter Rising). This war lasted from 28 June 1922 – 24 May 1923. Many of those who fought on both sides in the conflict had been members of the Irish Republican Army (Old IRA) during the War of Independence, including family members who fought each other, with atrocities and revenge killings on both sides. This caused great grief all around and led O'Doherty to become quite depressed at times.

The war came to an end a year and a month after it began, when the Free State forces, who benefited from substantial quantities of weapons provided by the British Government, defeated those who opposed the Treaty and the partition of Ireland.

Adventures in the US

In 1922–24 and 1925–26, Éamon de Valera sent him on two Republican missions to the US with Seán T. O'Kelly and Frank Aiken to lobby and raise funds for the civil war. He crossed the Atlantic aboard a luxury liner, where during a dinner party hosted by the ship's captain, another guest who was a world-famous boxer challenged him to a fight to entertain the passengers, but O'Doherty had to decline in order to avoid drawing attention to himself. Travelling under a false passport as a Presbyterian minister to Canada, he entered the US by crossing the border with help from Irish whiskey smugglers (this was during the Prohibition era when alcohol was illegal in the USA). He visited every capitol in all 50 contiguous US states, dropped thousands of fundraising leaflets from a biplane flying between Manhattan skyscrapers in New York, and lived there with his wife Margaret Clare O'Doherty in her flat at Columbus Circle, while she practised medicine at St. Vincent's hospital in Greenwich Village. He had an office at 8 East 41st. Street in Manhattan, New York. On 17 October 1924 the British Consulate General in New York issued him with a new British Passport under his own name. His related adventures included descending the Grand Canyon on horseback, being invited to join a police raid on an opium den in San Francisco's Chinatown.

Co-founding Fianna Fáil

In 1926 O'Doherty he left the Sinn Féin party's Ard Fheis (annual party conference) with Éamon de Valera and became a founder member of the new Fianna Fáil party. He lost his seat at the June 1927 general election but was re-elected again to the Dáil in the 1933 general election.

He was elected to the Senate of Ireland (Seanad Éireann) in 1928, serving as one of Fianna Fáil's first six elected Senators under the leadership of Joseph Connolly.

From 1929 to 1933 served as the County Manager of Carlow and Kildare, where he used his knowledge of dowsing to find water supplies for local towns.

In 1936 O'Doherty successfully sued Ernie O'Malley for libel. The incident in question involved a raid Michael Collins had proposed to take place on 1 October 1919 at Moville, County Donegal. O'Malley, in his book On Another Man's Wound, had implied that O'Doherty had refused to go. In fact, it had been agreed, without O'Doherty's intervention, that it would be inappropriate for a member of the Dáil to be involved.[7]

Family

O'Doherty and his wife had five children: Dr. Brid O'Doherty (1919–2018), a member of the Saint Louis order of nuns; Dr. Fíona O'Callaghan (1921–2003); Dr. Roisín McCallum (1924–2018); Sr. Deirdre O'Doherty (a nun with the Poor Clare order (1927–2007) in Newry; and David O'Docherty (1935–2010) a painter and traditional Irish musician.[8]

He died in 1979, the third last surviving member of the First Dáil, and is buried along with his wife in the Republican plot in Glasnevin Cemetery in Dublin.

References

- "Joseph O'Doherty". Oireachtas Members Database. Retrieved 8 March 2012.

- "General Registrar's Office". IrishGenealogy.ie. Retrieved 13 April 2017.

- O'Doherty, Brid. "Joseph O'Doherty TD - The proud Derry man who stood for Inishowen in first Dail". www.derryjournal.com. Retrieved 18 March 2019.

- Clavin, Terry (2009). "Séamus O'Doherty In O'Doherty, (Michael) Kevin". In McGuire, James; Quinn, James (eds.). Dictionary of Irish Biography. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- "Mr. Joseph O'Doherty". Irish Times Obituary. Retrieved 28 August 2012.

- "Joseph O'Doherty". ElectionsIreland.org. Retrieved 8 March 2012.

- Richard English, Ernie O'Malley: IRA Intellectual, p. 44, Oxford University Press, 1999, ISBN 0-19-820807-3

- Nun who became an expert in French Romanticism – Brid O'Doherty' Obituaries, Irish Times, Weekend Edition, 4 August 2018.