Labour Party (Ireland)

The Labour Party (Irish: Páirtí an Lucht Oibre, literally "Party of the Working People") is a social democratic[2][3][4][5] political party in the Republic of Ireland. Founded on 28 May 1912 in Clonmel, County Tipperary, by James Connolly, Jim Larkin and William O'Brien as the political wing of the Irish Trades Union Congress,[10] it describes itself as a "democratic socialist party" in its constitution.[11] Labour continues to be the political arm of the Irish trade union and labour movement and seeks to represent workers' interests in the Dáil and on a local level.

Labour Party Páirtí an Lucht Oibre | |

|---|---|

| Leader | Alan Kelly TD |

| Seanad Leader | Senator Ivana Bacik |

| Parliamentary Party Chairperson | Seán Sherlock TD |

| Chairperson | Jack O'Connor |

| General Secretary | Billie Sparks |

| Founder | |

| Founded | 28 May 1912 |

| Headquarters | 2 Whitefriars, Aungier Street, Dublin 2 |

| Youth wing | Labour Youth |

| Women's wing | Labour Women |

| LGBT wing | Labour LGBT |

| Membership (2020) | 3,000[1] |

| Ideology | |

| Political position | Centre-left[5][7][8][9] |

| European affiliation | Party of European Socialists |

| International affiliation | |

| European Parliament group | Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats |

| Colours | Red |

| Anthem | "The Red Flag" |

| Dáil Éireann | 6 / 160

|

| Seanad Éireann | 5 / 60

|

| European Parliament | 0 / 13

|

| Local government | 57 / 949

|

| Website | |

| labour | |

| Part of a series on |

| Organised labour |

|---|

|

Unlike the other main Irish political parties, Labour did not arise as a faction of the original Sinn Féin party (although it incorporated Democratic Left in 1999, a party that did trace its origins back to Sinn Féin). The party has served as a partner in coalition governments on seven occasions since its formation: six times in coalition either with Fine Gael alone or with Fine Gael and other smaller parties, and once with Fianna Fáil. This gives Labour a cumulative total of nineteen years served as part of a government, the second-longest total of any party in the Republic of Ireland after Fianna Fáil. The current party leader is Alan Kelly. It is currently the joint-fifth-largest party in Dáil Éireann, with six seats. It is the third-largest party in Seanad Éireann, with 5 seats. This makes Labour the fifth-largest party in the Oireachtas overall. The Labour Party is a member of the Progressive Alliance,[12] Socialist International,[13] and Party of European Socialists (PES).[14]

History

Foundation

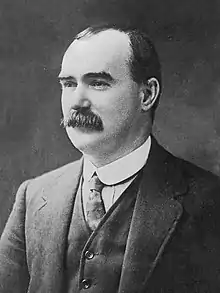

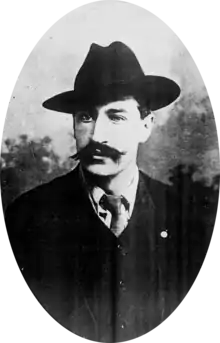

James Connolly, James Larkin and William O'Brien established the Irish Labour Party on 28 May 1912, as the political wing of the Irish Trades Union Congress.[15][16] This party was to represent the workers in the expected Dublin Parliament under the Third Home Rule Act 1914.[17] However, after the defeat of the trade unions in the Dublin Lockout of 1913 the labour movement was weakened; the emigration of James Larkin in 1914 and the execution of James Connolly following the Easter Rising in 1916 further damaged it.

The Irish Citizen Army (ICA), formed during the 1913 Lockout,[18] was informally the military wing of the Labour Movement. The ICA took part in the 1916 Rising.[19] Councillor Richard O'Carroll, a Labour Party member of Dublin Corporation, was the only elected representative to be killed during the Easter Rising. O'Carroll was shot and died several days later on 5 May 1916.[20] The ICA was revived during Peadar O'Donnell's Republican Congress but after the 1935 split in the Congress most ICA members joined the Labour Party.

The British Labour Party had previously organised in Ireland, but in 1913 the Labour NEC agreed that the Irish Labour Party would have organising rights over the entirety of Ireland. A group of trade unionists in Belfast objected and the Belfast Labour Party, which later became the nucleus of the Northern Ireland Labour Party, remained outside the new Irish party.

Early history

In Larkin's absence, William O'Brien became the dominant figure in the Irish Transport and General Workers' Union (ITGWU) and wielded considerable influence in the Labour Party. O'Brien also dominated the Irish Trades Union Congress. The Labour Party, led by Thomas Johnson from 1917,[21] as successor to such organisations as D. D. Sheehan's (independent Labour MPs) Irish Land and Labour Association, declined to contest the 1918 general election, in order to allow the election to take the form of a plebiscite on Ireland's constitutional status (although some candidates did run in Belfast constituencies under the Labour banner against Unionist candidates).[22] It also refrained from contesting the 1921 elections. As a result, the party was left outside Dáil Éireann during the vital years of the independence struggle, though Johnson sat in the First Dáil.

In the Irish Free State

The Anglo-Irish Treaty divided the Labour Party. Some members sided with the Irregulars in the Irish Civil War that quickly followed. O'Brien and Johnson encouraged its members to support the Treaty. In the 1922 general election the party won 17 seats.[21] However, there were a number of strikes during the first year and a loss in support for the party. In the 1923 general election the Labour Party only won 14 seats. From 1922 until Fianna Fáil TDs took their seats in 1927, the Labour Party was the major opposition party in the Dáil. Labour attacked the lack of social reform by the Cumann na nGaedheal government.

Larkin returned to Ireland in 1923. He hoped to resume the leadership role he had previously left, but O'Brien resisted him. Larkin sided with the more radical elements of the party, and in September that year he established the Irish Worker League.

In 1932, the Labour Party supported Éamon de Valera's first Fianna Fáil government, which had proposed a programme of social reform with which the party was in sympathy. It appeared for a time during the 1940s that the Labour Party would replace Fine Gael as the main opposition party. In the 1943 general election the party won 17 seats, its best result since 1927.

The party was socially conservative compared to similar European parties, and its leaders from 1932 to 1977 (William Norton and his successor Brendan Corish) were members of the Knights of Saint Columbanus.[23]

The split with National Labour and the first coalition governments

The Larkin-O'Brien feud still continued, and worsened over time. In the 1940s the hatred caused a split in the Labour Party and the Irish Congress of Trade Unions. O'Brien left with six TDs in 1944, founding the National Labour Party, whose leader was James Everett. O'Brien also withdrew ITGWU from the Irish Trades Unions Congress and set up his own congress. The split damaged the Labour movement in the 1944 general election. It was only after Larkin's death in 1947 that an attempt at unity could be made.

After the 1948 general election National Labour had five TDs – Everett, Dan Spring, James Pattison, James Hickey and John O'Leary. National Labour and Labour (with 14 TDs) both entered the First Inter-Party Government, with the leader of National Labour becoming Minister for Posts and Telegraphs. In 1950, the National Labour TDs rejoined the Labour Party.

From 1948 to 1951 and from 1954 to 1957, the Labour Party was the second-largest partner in the two inter-party governments (the largest being Fine Gael). William Norton, the Labour Party leader, became Tánaiste on both occasions. During the First Inter-Party Government he served as Minister for Social Welfare, while during the Second Inter-Party Government he served as Minister for Industry and Commerce. (See First Inter-Party Government and Second Inter-Party Government.)

In 1960, the Labour leader Brendan Corish described the party's programme as "a form of Christian socialism".[24]

Re-establishment in Northern Ireland

The Republic of Ireland Act 1948 and Ireland Act 1949 precipitated a split in the Northern Ireland Labour Party (NILP) with Jack Macgougan leading anti-Partition members out and affiliating branches to the Dublin party, joined by other left-wing and nationalist representatives and branded locally as "Irish Labour".[25] At Westminster, Jack Beattie held Belfast West from 1951 to 1955;[26] the British Labour party refused Beattie its whip.[27] At Stormont, Belfast Dock was won by Murtagh Morgan in 1953 and Paddy Devlin in 1962,[28] but Devlin in 1964 left for the Republican Labour Party and Irish Labour contested no further Westminster or Stormont elections.[25][29] In the 1949 local elections it won 7 seats on Belfast City Council, 6 (unopposed) on Armagh urban district council (UDC) and one on Dungannon UDC.[25] In Derry, the party collapsed when Stephen McGonagle left after 1952.[30] It was strongest in Warrenpoint and Newry UDCs, winning control of the former in 1949 and the latter in 1958, retaining seats in both until their 1973 abolition. Tommy Markey was expelled from the party in 1964 for taking a salute as Newry council chair from the Irish Guards.[31] Party branches still existed in Warrenpoint and Newry as late as 1982,[29] though candidates were heavily defeated in Newry and Mourne District Council at the 1973 local elections.[32] The Social Democratic and Labour Party founded in 1970 took most of Irish Labour's voters and soon had its formal endorsement.

Under Brendan Corish, 1960–77

Brendan Corish became the new Labour leader in 1960. As leader he advocated more socialist policies, and introduced them to the party. In 1972, the party campaigned against membership of the European Economic Community (EEC).[33] Between 1973 and 1977, the Labour Party formed a coalition government with Fine Gael. The coalition partners lost the subsequent 1977 general election, and Corish resigned immediately after the defeat.

Late 1970s and 1980s: Coalition, internal feuding, electoral decline and regrowth

In 1977, shortly after the election defeat, members grouped around the Liaison Committee for the Labour Left split from Labour and formed the short-lived Socialist Labour Party. From 1981 to 1982 and from 1982 to 1987, the Labour Party participated in coalition governments with Fine Gael. In the later part of the second of these coalition terms, the country's poor economic and fiscal situation required strict curtailing of government spending, and the Labour Party bore much of the blame for unpopular cutbacks in health and other public services. The nadir for the Labour party was the 1987 general election where it received only 6.4% of the vote. Its vote was increasingly threatened by the growth of the Marxist and more radical Workers' Party, particularly in Dublin. Fianna Fáil formed a minority government from 1987 to 1989 and then a coalition with the Progressive Democrats.

The 1980s saw fierce disagreements between the wings of the party. The more radical elements, Labour Left, led by such figures as Emmet Stagg, Sam Nolan, Frank Buckley and Helena Sheehan, and Militant Tendency, led by Joe Higgins, opposed the idea of Labour entering into coalition government with either of the major centre-right parties (Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael).[34][35] At the 1989 Labour Party conference in Tralee a number of socialist and Trotskyist activists, organised around the Militant Tendency and their internal newspaper, were expelled. These expulsions continued during the early 1990s and those expelled, including Joe Higgins, went on to found the Socialist Party.

1990s: Growing political influence and involvement

In 1990 Mary Robinson became the first President of Ireland to have been proposed by the Labour Party, although she contested the election as an independent candidate, she had resigned from the party over her opposition to the Anglo Irish Agreement. Not only was it the first time a woman held the office but it was the first time, apart from Douglas Hyde, that a non-Fianna Fáil candidate was elected. In 1990 Limerick East TD Jim Kemmy's Democratic Socialist Party merged into the Labour Party, and in 1992 Sligo–Leitrim TD Declan Bree's Independent Socialist Party also joined the Labour Party (in May 2007 Declan Bree resigned from the Labour Party over differences with the Leadership).[36])

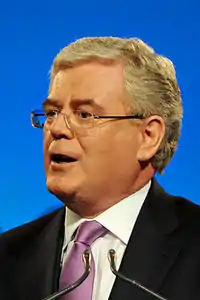

At the 1992 general election the Labour Party won a record 19.3% of the first preference votes, more than twice its share in the 1989 general election. The party's representation in the Dáil doubled to 33 seats and, after a period of negotiations, the Labour Party formed a coalition with Fianna Fáil, taking office in January 1993 as the 23rd Government of Ireland. Fianna Fáil leader Albert Reynolds remained as Taoiseach, and Labour Party leader Dick Spring became Tánaiste and Minister for Foreign Affairs.

After less than two years the government fell in a controversy over the appointment of Attorney General, Harry Whelehan, as president of the High Court. The parliamentary arithmetic had changed as a result of Fianna Fáil's loss of two seats in by-elections in June, where the Labour Party itself had performed disastrously. On the pretext that the Labour Party voters were not happy with involvement with Fianna Fáil, Dick Spring withdrew his support for Reynolds as Taoiseach. The Labour Party negotiated a new coalition, the first time in Irish political history that one coalition replaced another without a general election. Between 1994 and 1997 Fine Gael, the Labour Party, and Democratic Left governed in the 24th Government of Ireland. Dick Spring became Tánaiste and Minister for Foreign Affairs again.

Merger with Democratic Left

The Labour Party presented the 1997 general election, held just weeks after spectacular electoral victories for the French Socialist Party and British Labour Party, as the first-ever choice between a government of the left and one of the right; but the party, as had often been the case following its participation in coalitions, lost support and lost half of its TDs. Labour's losses were so severe that while Fine Gael gained seats, it still came up well short of the support it needed to keep Bruton in office. This, combined with a poor showing by Labour Party candidate Adi Roche in the subsequent election for President of Ireland, led to Spring's resignation as party leader.

In 1997 Ruairi Quinn became the new Labour Party leader. Following negotiations in 1999, the Labour Party merged with Democratic Left, keeping the name of the larger partner. This had been previously opposed by the former leader Dick Spring. Members of Democratic Left in Northern Ireland were invited to join the Irish Labour Party but not permitted to organise.[37] This left Gerry Cullen, their councillor in Dungannon Borough Council, in a state of limbo; he had been elected for a party he could no longer seek election for. [38]

The launch was held in the Pillar Room of the Rotunda Hospital in Dublin.[39]

Quinn resigned as leader in 2002 following the poor results for the Labour Party in the 2002 general election. Former Democratic Left TD Pat Rabbitte became the new leader, the first to be elected directly by the members of the party.

In the 2004 elections to the European Parliament, Proinsias De Rossa retained his seat for the Labour Party in the Dublin constituency. This was the Labour Party's only success in the election. In the local elections held the same day, the Labour Party won over 100 county council seats, the first time ever in its history, and emerged as the largest party in Dublin city and Galway city.

2007 general election and aftermath

| Part of a series on |

| Social democracy |

|---|

|

|

Prior to the 2004 local elections, Party Leader Pat Rabbitte had endorsed a mutual transfer pact with Fine Gael leader Enda Kenny. Rabbitte proposed the extension of this strategy, named "the Mullingar Accord" after a meeting between Rabbitte and Kenny in the County Westmeath town, at the 2005 Labour Party National Conference.

Rabbitte's strategy was favoured by most TDs, notably Deputy Leader Liz McManus, Eamon Gilmore—who had proposed a different electoral strategy in the 2002 leadership election—and former opponent of coalition Emmet Stagg. Opposition to the strategy came from Brendan Howlin, Kathleen Lynch and Tommy Broughan (who is regarded as being on the party's left wing and who advocated closer co-operation with the Green Party and Sinn Féin),[40] who opposed the boost that would be given to Fine Gael in such a strategy and stated their preference for an independent campaign. Outside the PLP, organised opposition to the pact came from Labour Youth and the ATGWU, who opposed the pact on political and tactical grounds. Nevertheless, the strategy proposed by Rabbitte was supported by approximately 80% of conference delegates.

In the 2007 general election the Labour Party failed to increase its seat total and had a net loss of 1 seat, returning with 20 seats. Fine Gael, the Labour Party, the Green Party and independents did not have enough seats to form a government. Pat Rabbitte resisted calls to enter negotiations with Fianna Fáil on forming a government. Eventually, Fianna Fáil entered government with the Progressive Democrats and the Green Party with the support of independents.

On 23 August 2007 Rabbitte resigned as Labour Party leader. He stated that he took responsibility for the outcome of the recent general election, in which his party failed to gain new seats and failed to replace the outgoing government.

On 6 September 2007 Eamon Gilmore was unanimously elected leader of the Labour Party, being the only nominee after Pat Rabbitte's resignation.

2009 local and European elections

At the local elections of 5 June 2009, the Labour Party added to its total of council seats, with 132 seats won (+31) and gained an additional two seats from councillors joining the party since the election. On Dublin City Council, the party was again the largest party, but now with more seats than the two other main parties combined. The Labour Party's status as the largest party on both Fingal and South Dublin councils was also improved by seat gains.

At the 2009 European Parliament election held on the same day, the Labour Party increased its number of seats from one to three, retaining the seat of Proinsias De Rossa in the Dublin constituency, while gaining seats in the East constituency with Nessa Childers, and in the South constituency with Alan Kelly. This was the first time since the 1979 European Parliament Elections that Labour equalled the number of seats held in Europe by either Fianna Fáil or Fine Gael.[41]

2011 Government and decline in support

On 11 June 2010, a poll by MRBI was published in The Irish Times which, for the first time in the history of the state, showed the Labour Party as the most popular, at 32%, ahead of Fine Gael at 28% and Fianna Fáil at 17%. Eamon Gilmore's approval ratings were also the highest of any Dáil leader, standing at 46%.[42]

At the 2011 general election, Labour received 19.5% of first preference votes, and 37 seats.[43] On 9 March 2011, it became the junior partner in a coalition government with Fine Gael for the period of the 31st Dáil.[44] Eamon Gilmore was appointed as Tánaiste (deputy prime minister) and Minister for Foreign Affairs and Trade.

In October 2011 the Labour Party's candidate, Michael D. Higgins was elected as the 9th President of Ireland. On the same day, Labour's Patrick Nulty won the Dublin West by-election, making the Labour Party the first government party in Ireland to win a by-election since 1982.

Labour lost seven parliamentary members over the course of the 31st Dáil. On 15 November 2011 Willie Penrose resigned over the closure of an army barracks in his constituency.[45] On 1 December 2011 Tommy Broughan lost the party whip after voting against the government in relation to the Bank Guarantee Scheme.[46] On 6 December 2011 Patrick Nulty lost the party whip after voting against the VAT increase in the 2012 budget.[47] On 26 September 2012 Róisín Shortall resigned as Minister of State for Primary Care and lost the party whip after conflict with the Minister for Health James Reilly.[48] On 13 December 2012 Colm Keaveney lost the party whip after voting against the cut to the respite care grant in the 2013 budget.[49] Senator James Heffernan lost the party whip in December 2012 after voting against the government on the Social Welfare Bill.[50] MEP Nessa Childers resigned from the parliamentary party on 5 April 2013, saying that she "no longer want[ed] to support a Government that is actually hurting people",[51] and she resigned from the party in July 2013. In June 2013, Patrick Nulty and Colm Keaveney resigned from the Labour Party.[52] Willie Penrose returned to the parliamentary Labour Party in October 2013.[53]

On 26 May 2014, Gilmore resigned as party leader after Labour's poor performance in the European and local elections. On 4 July 2014, Joan Burton won the leadership election, defeating Alex White by 78% to 22%.[54] On her election, she said that the Labour Party "would focus on social repair, and govern more with the heart".[54] Burton was the first woman to lead the Labour Party.

Analysis of budgets

Budgets 2012 to 2016 – introduced in part by Brendan Howlin as Minister for Public Expenditure and supported by Labour[55] – were described by the Economic and Social Research Institute (ESRI) as “unable to be characterised in terms of simple patterns of progressivity or regressivity” and that "over a substantial range the pattern is broadly proportional, but this does not extend to whole income distribution". The ESRI went on to say that "The greatest policy-induced losses have been at the top of the income distribution".

It found “Budget 2012 involved greater proportionate losses for those on low incomes: reductions of about 2 to 2½ per cent for those with the lowest incomes, as against losses of about ¾ of a per cent for those on the highest incomes”.

By contrast, the ESRI found earlier budgets in 2008–2010 to be “strongly progressive” because before 2011 “Losses imposed by policy changes in tax and welfare have been greatest for those on the highest incomes, and smaller for those on low incomes”.[56]

However, it concluded “Budget 2014 had its greatest impact – a reduction of 2 per cent – on low income groups. The lowest impact was on some middle income groups (a loss of 1 to 1¼ per cent) while the top income group lost slightly less than 1¾ per cent – somewhat more than the middle, and less than the bottom income group.”[57] The ESRI described the overall impact of Budget 2015 as "close to neutral, increasing average income by less than 0.1 per cent."[58] The ESRI found that Budget 2016 "led to a modest increase – just under 0.7 per cent – in aggregate household disposable income.[59]

2016 general election

In the 2016 general election, Labour achieved a poor result, receiving only 6.6% of first preference votes, and 7 seats.[60] It was the worst general election in its history, with a loss of 30 seats on its showing in 2011.[61]

After 2016

.jpg.webp)

On 20 May 2016, Brendan Howlin was elected unopposed as leader; some controversy arose from the fact that there was no contest for the leadership because none of his parliamentary colleagues were prepared to second the nomination of Alan Kelly.[62] Howlin stated that as leader he was prepared to bring Labour back into government, citing the lack of influence on policy from opposition.[63] He denied any suggestions that Labour could lose any further support from their 2016 performance, stating "We’re not some outfit that comes out of the morning mist and disappears again. We're the oldest party in the state".[64]

Two Labour councillors resigned from the party in late 2018 - Martina Genockey and Mick Duff, both based in Dublin.[65]

In the Local and European Elections of May 2019, despite a decreased vote share by 1.4%, Labour increased their seat count on local authorities to 57, an increase of 6. This maintained Labour's position as the country's 4th-largest party at local government level. However, the party failed to win a European seat with their three candidates, Alex White, Sheila Nunan and Dominic Hannigan, leaving the S&D Group unrepresented by an Irish MEP for the first time since 1984.

At the February 2020 election, the party's first preference vote dropped to 4.4%, a record low. While the party made gains in Dublin Bay North and Louth, Joan Burton and Jan O'Sullivan both lost their seats and the party failed to retain its seat in Longford-Westmeath caused by the retirement of Willie Penrose. In addition former TDs Emmet Stagg, Joanna Tuffy, and Joe Costello failed to re-capture the seats they lost in 2016.[66] In the subsequent Seanad Elections, Labour won 5 seats, which tied them with Sinn Féin as the third-largest party in the House.

After the General Election, Brendan Howlin announced his intention to step down as the leader of the Labour Party.[67] On 3 April 2020 Alan Kelly was elected as party leader, edging out fellow Dáil colleague Aodhán Ó Ríordáin 55% to 45%.[68]

Ideology and policies

The Labour Party are a party of the centre-left[10][12][13][14] who have been described as a social democratic party[3] but are referred to in their constitution as a democratic socialist party.[11] Their constitution refers to the party as a "movement of democratic socialists, social democrats, environmentalists, progressives, feminists (and) trade unionists".[11]

LGBT rights policies

The Labour Party have been involved in various campaigns for LGBT rights and put forward many bills. The party were in government in 1993 when homosexuality was decriminalised in Ireland.[69] Mervyn Taylor published the Employment Equality Bill in 1996, which was enacted in 1998, outlawing discrimination in the workplace on the grounds of sexual orientation. Taylor also published the Equal Status Bill in 1997, enacted in 2000, outlawing discrimination in the provision of goods and services on grounds listed including sexual orientation.[70]

At the 2002 general election, only the manifestos of the Green Party and Labour explicitly referred to the rights of same-sex couples.[71]

In 2003, Labour LGBT was founded. This was the first time a political party in Ireland had formed an LGBT wing.[70]

In December 2006, Labour TD Brendan Howlin tabled a private member's civil unions bill in Dáil Éireann,[72] proposing the legalization of civil partnerships and adoption for same-sex couples.[73] The Fianna Fáil government amended the bill to delay it for six months time, however the Dáil was dissolved for the 2007 Irish general election before this could happen. Labour again brought this bill before the Dáil in 2007 but it was voted down by the government, with the Green Party, who had formerly supported gay marriage, also voting in opposition to the bill, with spokesperson Ciarán Cuffe arguing that the bill was unconstitutional.

At their 2010 national conference Labour passed a motion calling for transgender rights and to legislate for a gender recognition act.[70]

During their time in government, Ireland became the first country to legalise gay marriage by popular vote.[74]

Social policies

Labour supported the repeal of the Eighth Amendment of the Constitution of Ireland in 2018[75] to legalize abortion, and canvassed for a Yes vote in that referendum.[76]

Labour leader Alan Kelly sponsored a bill in 2020 that called for all workers to receive a legal right to sick pay, as well as paid leave for employees whose children have to stay home from school due to COVID-19 measures.[77] The government amended this bill to delay it for six months, a decision that senator Marie Sherlock branded as "unacceptable".[78]

Education policies

In 2020, Labour TD Aodhán Ó Riordáin successfully campaigned for Ireland's free school meals campaign to be extended across summer.[79]

Labour have called for all primary education to be made free by providing grants for books, uniforms and students, and ending the two tier pay system for teachers and secretaries.[80]

Housing policies

Labour launched their housing policies in 2020, and proposed building 80,000 social and affordable houses, investing 16 billion euro into housing and freezing rents.[81]

Health policies

In their 2020 manifesto, Labour proposed spending an additional 1 billion euro per year on health and delivering free GP care for all under 18s.[82]

The party has pledged to spend 40 million euro over three years on University Hospital Limerick to combat the under-funding of the hospital.[83]

Climate policies

In their climate manifesto in 2020, the party called for halving the country's emissions by 2030, supporting farms transitioning to more environmental forms of farming, restoring peatlands and bogs, banning offshore drilling and supporting a just transition.[80]

Drug policies

In 2017, Labour leader Brendan Howlin became the first traditional party leader to back the full decriminalization of cannabis in Ireland. This came after a motion endorsed by Aodhán O'Riordáin supporting the legalization of cannabis for recreational usage was passed at Labour conference.[84] O'Riordáin had previously voiced his support for the decriminalization of all drugs, stating that "About 70 per cent of the drugs cases that are before our courts at the moment are for possession for personal use, which to be honest is a complete waste of garda time and criminal justice time", saying that someone suffering from addiction "is fundamentally a patient, who should be surrounded by compassion, not somebody who should be sitting in a court room."[85]

The current party leader Alan Kelly has previously stated that he supports the legalization of marijuana in Ireland on both medicinal and recreational grounds.[86]

In their 2020 manifesto, Labour called for expanding public access to anti-overdose drugs such as Naloxone, and ending the penalization for possession of small amounts of drugs, but focusing on punishing drug trafficking.[87]

Cultural policies

The party has called for a campaign to promote the usage of spoken Irish, funding outreach initiatives for minorities and marginalized communities and creating a fund for artists.[80]

Historical archives

The Labour Party donated its archives to the National Library of Ireland in 2012. The records can be accessed by means of the call number: MS 49,494.[88] Subsequently, the records of Democratic Left were also donated to the library and can be access via the call number: MS 49,807.[89]

General election results

| Election | Seats won | ± | Position | First Pref votes | % | Government | Leader |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1922 | 17 / 128 |

132,565 | 21.3% | Opposition (CnaG minority) | Thomas Johnson | ||

| 1923 | 14 / 153 |

111,939 | 10.6% | Opposition (CnaG minority) | Thomas Johnson | ||

| 1927 (Jun) | 22 / 153 |

143,849 | 12.6% | Opposition (CnaG minority) | Thomas Johnson | ||

| 1927 (Sep) | 13 / 153 |

106,184 | 9.1% | Opposition (CnaG minority) | Thomas Johnson | ||

| 1932 | 7 / 153 |

98,286 | 7.7% | Confidence and supply (FF minority) | Thomas J. O'Connell | ||

| 1933 | 8 / 153 |

79,221 | 5.7% | Confidence and supply (FF minority) | William Norton | ||

| 1937 | 13 / 138 |

135,758 | 10.3% | Confidence and supply (FF minority) | William Norton | ||

| 1938 | 9 / 138 |

128,945 | 10.0% | Opposition (FF) | William Norton | ||

| 1943 | 17 / 138 |

208,812 | 15.7% | Opposition (FF minority) | William Norton | ||

| 1944 | 8 / 138 |

106,767 | 8.8% | Opposition (FF) | William Norton | ||

| 1948 | 14 / 147 |

115,073 | 8.7% | Coalition (FG–LP–CnP–CnT–NLP) | William Norton | ||

| 1951 | 16 / 147 |

151,828 | 11.4% | Opposition (FF minority) | William Norton | ||

| 1954 | 19 / 147 |

161,034 | 12.1% | Coalition (FG–LP–CnT) | William Norton | ||

| 1957 | 12 / 147 |

111,747 | 9.1% | Opposition (FF) | William Norton | ||

| 1961 | 16 / 144 |

136,111 | 11.6% | Opposition (FF minority) | Brendan Corish | ||

| 1965 | 22 / 144 |

192,740 | 15.4% | Opposition (FF) | Brendan Corish | ||

| 1969 | 18 / 144 |

224,498 | 17.0% | Opposition (FF) | Brendan Corish | ||

| 1973 | 19 / 144 |

184,656 | 13.7% | Coalition (FG–LP) | Brendan Corish | ||

| 1977 | 17 / 148 |

186,410 | 11.6% | Opposition (FF) | Brendan Corish | ||

| 1981 | 15 / 166 |

169,990 | 9.9% | Coalition (FG–LP minority) | Frank Cluskey | ||

| 1982 (Feb) | 15 / 166 |

151,875 | 9.1% | Opposition (FF minority) | Michael O'Leary | ||

| 1982 (Nov) | 16 / 166 |

158,115 | 9.4% | Coalition (FG–LP) | Dick Spring | ||

| 1987 | 12 / 166 |

114,551 | 6.4% | Opposition (FF minority) | Dick Spring | ||

| 1989 | 15 / 166 |

156,989 | 9.5% | Opposition (FF–PD) | Dick Spring | ||

| 1992 | 33 / 166 |

333,013 | 19.3% | Coalition (FF–LP) Coalition (FG–LP–DL from 1994) |

Dick Spring | ||

| 1997 | 17 / 166 |

186,044 | 10.4% | Opposition (FF) | Dick Spring | ||

| 2002 | 20 / 166 |

200,130 | 10.8% | Opposition (FF) | Ruairi Quinn | ||

| 2007 | 20 / 166 |

209,175 | 10.1% | Opposition (FF) | Pat Rabbitte | ||

| 2011 | 37 / 166 |

431,796 | 19.5% | Coalition (FG–LP) | Eamon Gilmore | ||

| 2016 | 7 / 158 |

140,898 | 6.6% | Opposition (FG–Ind minority) | Joan Burton | ||

| 2020[91] | 6 / 160 |

95,582 | 4.4% | Opposition (FF-FG-Green) | Brendan Howlin |

Westminster

| Election | Leader | Seats | Government | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | ± | |||

| 1950 | William Norton | 0 / 625 |

N/A | |

| 1951 | William Norton | 1 / 625 |

Conservative | |

| 1955 | William Norton | 0 / 630 |

N/A | |

Stormont

| Election | Body | Seats | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1953 | 8th Parliament | 1 / 52 |

UUP Majority |

| 1958 | 9th Parliament | 0 / 52 |

UUP Majority |

| 1962 | 10th Parliament | 1 / 52 |

UUP Majority |

Structure

The Labour Party is a membership organisation consisting of Labour (Dáil) constituency councils, affiliated trade unions and socialist societies. Members who are elected to parliamentary positions (Dáil, Seanad, European Parliament) form the Parliamentary Labour Party (PLP). The party's decision-making bodies on a national level formally include the Executive Board (formerly known as the National Executive Committee), Labour Party Conference and Central Council. The Executive Board has responsibility for organisation and finance, with the Central Council being responsible for policy formation – although in practice the Parliamentary leadership has the final say on policy. The Labour Party Conference debates motions put forward by branches, constituency councils, party members sections and affiliates. Motions set principles of policy and organisation but are not generally detailed policy statements.

For many years Labour held to a policy of not allowing residents of Northern Ireland to apply for membership, instead supporting the Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP). The National Conference approved the establishment of a Northern Ireland Members Forum but it has not agreed to contest elections there.

As a party with a constitutional commitment to democratic socialism[92] founded by trade unions to represent the interests of working class people, Labour's link with unions has always been a defining characteristic of the party. Over time this link has come under increasing strain, with most craft based unions based in the public sector and Irish Congress of Trades Unions having disaffiliated since the 1950s. The remaining affiliated unions are primarily private sector general unions. Currently affiliated unions still send delegates to the National Conference in proportion to the size of their membership. Recent constitutional changes mean that in future, affiliated unions will send delegations based on the number of party members in their organisation.

Sections

Within the Labour Party there are different sections:

- Labour Youth

- Labour Women

- Labour Trade Unionists

- Labour Councillors

- Labour Equality (this section also includes groups such as Labour LGBT)

- Labour Disability

Affiliates

The Irish Labour Party constitution makes provision for both Trade Unions and Socialist Societies to affiliate to the party. There are currently seven Trade Unions affiliated to the Party:

- Munster & District Graphical Society

- Fórsa (Municipal Employees Division)

- National Union of Rail, Maritime and Transport Workers (RMT)

- General, Municipal and Boilermakers' Union (GMB)

- Services, Industrial, Professional and Technical Union (SIPTU)

- Bakers, Food and Allied Workers Union (BFWAU)

- Transport Salaried Staffs Association (TSSA)

Socialist Societies Affiliated to the Party:

- Labour Party Lawyers Group

- Association of Labour Teachers

- Labour Social Services Group

Leadership

Party leader

The following are the terms of office as party leader and as Tánaiste:

| Name | Portrait | Period | Constituency | Years as Tánaiste (if applicable) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thomas Johnson |  |

1917–1927 | Dublin County | |

| Thomas J. O'Connell |  |

1927–1932 | Mayo South | |

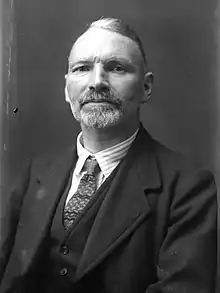

| William Norton |  |

1932–1960 | Kildare | 1948–1951; 1954–57 (Government of the 13th Dáil and 15th Dáil) |

| Brendan Corish |  |

1960–1977 | Wexford | 1973–77 (Government of the 20th Dáil) |

| Frank Cluskey | 1977–1981 | Dublin South-Central | ||

| Michael O'Leary | 1981–1982 | Dublin North-Central | 1981–Feb. 1982 (Government of the 22nd Dáil) | |

| Dick Spring |  |

1982–1997 | Kerry North | Nov. 1982–87; 1992–97 (Government of the 24th Dáil, 23rd Government of Ireland and 24th Government of Ireland) |

| Ruairi Quinn |  |

1997–2002 | Dublin South-East | |

| Pat Rabbitte | .jpg.webp) |

2002–2007 | Dublin South-West | |

| Eamon Gilmore | .jpg.webp) |

2007–2014 | Dún Laoghaire | 2011–14 (Government of the 31st Dáil) |

| Joan Burton | .jpg.webp) |

2014–2016 | Dublin West | 2014–2016 (Government of the 31st Dáil) |

| Brendan Howlin | _2020_(cropped).jpg.webp) |

2016–2020 | Wexford | |

| Alan Kelly | _2020_(cropped).png.webp) |

2020- | Tipperary |

Deputy leader

| Name | Period | Constituency |

|---|---|---|

| Barry Desmond | 1982–1989 | Dún Laoghaire |

| Ruairi Quinn | 1989–1997 | Dublin South-East |

| Brendan Howlin | 1997–2002 | Wexford |

| Liz McManus | 2002–2007 | Wicklow |

| Joan Burton | 2007–2014 | Dublin West |

| Alan Kelly | 2014–2016 | Tipperary North |

Seanad leader

| Name | Period | Panel |

|---|---|---|

| Michael Ferris | 1981–1989 | Agricultural Panel |

| Jack Harte | 1989–1993 | Labour Panel |

| Jan O'Sullivan | 1993–1997 | Administrative Panel |

| Joe Costello | 1997–2002 | Administrative Panel |

| Brendan Ryan | 2002–2007 | National University of Ireland |

| Alex White | 2007–2011 | Cultural and Educational Panel |

| Phil Prendergast | 2011 (acting) | Labour Panel |

| Ivana Bacik | 2011–present | University of Dublin |

Elected Representatives

Parliamentary Labour Party

The Parliamentary Labour Party (PLP) is the section of the party that is made up of its members of the Houses of the Oireachtas and of the European Parliament. As of April 2020 there are 11 members of the PLP: 6 TDs and 5 Senators.

Labour Party TDs in the 33rd Dáil Éireann (2020- )

| Name | Constituency |

|---|---|

| Alan Kelly | Tipperary |

| Brendan Howlin | Wexford |

| Ged Nash | Louth |

| Aodhán Ó Ríordáin | Dublin Bay North |

| Seán Sherlock | Cork East |

| Duncan Smith | Dublin Fingal |

Labour Party Senators in the 26th Seanad Éireann (2020- )

| Name | Constituency |

|---|---|

| Ivana Bacik | University of Dublin |

| Annie Hoey | Agricultural Panel |

| Rebecca Moynihan | Administrative Panel |

| Marie Sherlock | Labour Panel |

| Mark Wall | Industrial and Commercial Panel |

Front Bench

Councillors

At the 2014 local elections Labour lost more than half of local authority seats; 51 councillors were elected - this result led to the resignation of party leader, Eamon Gilmore. Following the 2019 Irish local elections, the party had 57 local representatives.[93]

See also

References

- Kenny, Aisling (13 April 2020). "Covid-19 to hit parties' votes on government formation". RTÉ. Retrieved 13 April 2020.

- Nordsieck, Wolfram (2020). "Ireland". Parties and Elections in Europe.

- Dimitri Almeida (2012). The Impact of European Integration on Political Parties: Beyond the Permissive Consensus. CRC Press. p. 61. ISBN 978-1-136-34039-0. Retrieved 14 July 2013.

- Richard Collin; Pamela L. Martin (2012). An Introduction to World Politics: Conflict and Consensus on a Small Planet. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 218. ISBN 978-1-4422-1803-1. Retrieved 18 July 2013.

- Richard Dunphy (2015). "Ireland". In Donatella M. Viola (ed.). Routledge Handbook of European Elections. Routledge. pp. 247–248. ISBN 978-1-317-50363-7.

- "Labour Party Constitution". 23 April 2017.

OUR PARTY is a democratic socialist party and, through its membership of the Party of European Socialists and the Progressive Alliance, is part of the international socialist movement working forequality and to empower of citizens, consumers and workers in a world increasingly dominated by big business, greed and selfishness.

- Paul Teague; James Donaghey (2004). "The Irish Experiment in Social Partnership". In Harry Charles Katz; Wonduck Lee; Joohee Lee (eds.). The New Structure of Labor Relations: Tripartism and Decentralization. Cornell University Press. p. 17. ISBN 0-8014-4184-6.

- Brigid Laffan; Jane O'Mahony (2008). Ireland and the European Union. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 142. ISBN 978-1-137-04835-6.

- Fiona Buckley (16 March 2016). Michelle Ann Miller; Tim Bunnell (eds.). Politics and Gender in Ireland. p. 32. ISBN 978-1134908769.

- "Labour's proud history". labour.ie. Retrieved 1 January 2011.

- "Party Constitution". labour.ie. Retrieved 18 March 2016.

- "Participants". Archived from the original on 2 March 2015. Retrieved 25 July 2015.

- "Socialist International – Progressive Politics For A Fairer World". Retrieved 25 July 2015.

- "Parties". Party of European Socialists. Archived from the original on 24 July 2015. Retrieved 25 July 2015.

- "Labour's proud history". Labour.ie. Retrieved 5 June 2018.

The Labour Party was founded in 1912 in Clonmel, County Tipperary, by James Connolly, James Larkin and William O'Brien as the political wing of the Irish Trades Union Congress

- Lyons, F.S.L. (1973). Ireland since the famine. Suffolk: Collins/Fontana. p. 281. ISBN 0-00-633200-5.

- "Annual Report" (PDF). Irish Trades Union Congress. 1912. p. 12.

- "The Irish Citizen Army : Labour clenches its fist!". Archived from the original on 2 February 2015. Retrieved 25 July 2015.

- "History – 1916 Easter Rising – Profiles – Irish Citizen Army". BBC. Retrieved 1 January 2011.

- "Richard O'Carroll T.C. (1876–1916)". Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 25 July 2015.

- O'Leary, Cornelius (1979). Irish elections 1918–77: parties, voters and proportional representation. Dublin: Gill and Macmillan. ISBN 0-7171-0898-8.

- "Election Results of 14 December 1918". Electionsireland.org. Retrieved 1 January 2011.

- Michael O'Leary Interview (6 December 2009). "The age of our craven deference is finally over". Independent.ie. Retrieved 1 January 2011.

- Paul Bew, Ellen Hazelkorn and Henry Patterson, The Dynamics of Irish Politics (London: Lawrence & Wishart, 1989), p. 85

- Norton, Christopher (1996). "The Irish Labour Party In Northern Ireland, 1949-1958". Saothar. 21: 47–59. JSTOR 23197182.

- "Election History of John (Jack) Beattie". www.electionsireland.org. Retrieved 1 January 2011.

- Edwards, Aaron (2009). A History of the Northern Ireland Labour Party: Democratic Socialism and Sectarianism. Oxford University Press. p. 45. ISBN 9780719078743. Retrieved 11 August 2018.

- Bardon, Jonathan (1992). A History of Ulster. Belfast: The Black Staff Press. p. 523. ISBN 0-85640-466-7.

- McAllister, Ian; Rose, Richard (1982). "3. Political parties > 3.3 Northern Ireland > Irish Labour Party". United Kingdom Facts. Springer. p. 81. ISBN 9781349042043. Retrieved 11 August 2018.

- Purdie, Bob (1990). "Derry and its Action Committees" (PDF). Politics in the Streets: The origins of the civil rights movement in Northern Ireland. Blackstaff Press. p. 167. ISBN 0-85640-437-3. Retrieved 11 August 2018.

- Boyle, Fabian. ""Box Factory," Road And Port Key To Prosperity (Part 2)". Newry Memoirs.

- The Local Government Elections 1973–1981: Newry and Mourne, Northern Ireland Elections

- "Death of a Former Member: Expressions of Sympathy". Office of the Houses of the Oireachtas. 2 March 2010. Retrieved 27 January 2012.

- Kenny, Brian (2010). Sam Nolan: A Long March on the Left. Dublin: Personal History Publishing.

- Sheehan, Helena (2019). Navigating the Zeitgeist. New York: Monthly Review Press.

- "Declan Bree resigns from Labour". Indymedia.ie. 16 May 2007. Retrieved 1 January 2011.; Bree, Declan. "DECLAN BREE RESIGNS FROM LABOUR PARTY". Declanbree.com. Retrieved 1 January 2011.

- Steven King on Thursday, Steven King, Belfast Telegraph, 17 December 1998

- "The 1993 Local Government Elections in Northern Ireland". Ark.ac.uk. Retrieved 1 January 2011.

- Lanson Kelly (25 January 1999). "Red rose shapes up to future by Liam O'Neill". Archives.tcm.ie. Archived from the original on 27 May 2003. Retrieved 1 January 2011.

- "Labour rift ahead of leader vote". Irish Independent. 26 August 2007.

- "Elections Ireland: 1979 European Election". www.electionsireland.org.

- "Labour and Gilmore enjoy significant gains in popularity". The Irish Times. 11 June 2010. Retrieved 1 January 2011.

- Doyle, Kilian (2 February 2011). "Kenny leads Fine Gael to win as Fianna Fáil vote collapses". The Irish Times.

- "FG and Labour discuss programme for government". RTÉ. 6 March 2011. Retrieved 6 March 2011.

- "Minister's resignation increases fears over budget cuts". The Irish Times. 16 November 2011.

- "Strike three: Broughan finds himself back outside the tent". Irish Independent. 3 December 2011.

- "Labour TD votes against Vat measure". The Irish Times. 6 December 2011.

- "Roisin Shortall resigns as junior health minister". RTÉ News. 26 September 2012.

- "Labour chairman Keaveney votes against Government". The Irish Times. Retrieved 13 December 2012.

- "Heffernan defies Labour whip on Bill". The Irish Times. 20 December 2012.

- "MEP Nessa Childers resigns from Parliamentary Labour Party". RTÉ News. 5 April 2013.

- "Patrick Nulty resigns from Labour Party". RTÉ News. 21 June 2013.

- "Penrose welcomed 'back into Labour fold' by Gilmore". TheJournal.ie. 7 October 2013.

- "Need to govern with more heart, says Joan Burton". RTÉ News. 4 July 2014.

- Mary Minihan (7 December 2011). "Noonan, Howlin defend budget cuts". Retrieved 14 December 2017.

- Tim Callan; Claire Keane; Michael Savage; John R. Walsh (24 February 2012). "Distributional Impact of Tax, Welfare and Public Sector Pay Policies: 2009‐2012" (PDF). Retrieved 4 November 2017.

- Tim Callan; Claire Keane; Michael Savage; John R. Walsh (12 December 2013). "Distributional Impact of Tax, Welfare and Public Service Pay Policies: Budget 2014 and Budgets 2009-2014" (PDF). Retrieved 4 November 2017.

- Claire Keane; Tim Callan; Michael Savage; John R. Walsh; Brian Colgan (12 December 2014). "Distributional Impact of Tax, Welfare and Public Service Pay Policies: Budget 2015 and Budgets 2009-2015" (PDF). Retrieved 4 November 2017.

- Catriona Logue; Tim Callan; Michael Savage; John R. Walsh; Brian Colgan (16 December 2015). "Distributional Impact of Tax, Welfare and Public Service Pay Policies: Budget 2016 and Budgets 2009-2016". Retrieved 30 July 2020.

- "Labour and Gilmore enjoy significant gains in popularity". RTÉ. 29 February 2016. Retrieved 29 February 2016.

- "Labour just had the worst election in its 104-year history". The Journal. 3 March 2016. Retrieved 3 March 2016.

- "Brendan Howlin becomes new Labour Party leader". RTÉ. 20 May 2016. Retrieved 20 May 2016.

- "Labour Party prepared to go back into government, says Howlin - Independent.ie".

- "Labour leader Brendan Howlin open to coalition with Fianna Fáil and Sinn Féin". 21 April 2017.

- McConnell, Daniel (5 October 2018). "Second Labour councillor resigns claiming party is on the 'road to oblivion'". Irish Examiner. Retrieved 6 October 2018.

- McCrave, Conor (10 February 2020). "'We were blindsided by the surge of votes for Sinn Féin': Is there a future for the Labour Party after yet another dismal election?". TheJournal.ie. Archived from the original on 11 February 2020. Retrieved 12 February 2020.

- Leahy, Pat; McDonagh, Marese. "Labour Party leader Brendan Howlin announces resignation". Irish Times. Retrieved 12 February 2020.

- Lehane, Mícheál (3 April 2020). "Alan Kelly elected new leader of Labour Party". RTÉ.

- Croffey, Amy. "20 years ago homosexuality was decriminalised, but not everyone was happy..." TheJournal.ie. Retrieved 16 October 2020.

- "The Labour Party's Proud LGBT History". The Labour Party.

- "Labour Party (Ireland) 2002 general election Manifesto" (PDF). Labour Party (Ireland). 2002.

- "Labour to table civil unions Bill". The Irish Times. Retrieved 16 October 2020.

- Oireachtas, Houses of the (14 December 2006). "Civil Unions Bill 2006 – No. 68 of 2006 – Houses of the Oireachtas". www.oireachtas.ie. Retrieved 16 October 2020.

- McDonald, Henry (23 May 2015). "Ireland becomes first country to legalise gay marriage by popular vote". The Observer. ISSN 0029-7712. Retrieved 16 October 2020.

- O'Regan, Michael. "Majority Fine Gael view on abortion referendum expected". The Irish Times. Retrieved 16 October 2020.

- "Labour's Higgins re-election spend to equal repeal campaign outlay". independent. Retrieved 16 October 2020.

- "Lewis Silkin - Proposed new rights to sick pay and parental leave pay in Ireland". Lewis Silkin. Retrieved 16 October 2020.

- "Delay to sick pay bill branded 'unacceptable' by Labour TD". Breaking News. 23 September 2020. Retrieved 16 October 2020.

- Beresford, Jack. "Free school meals programme for Ireland's poorest families to continue over summer". Irish Post.

- Maguire, Adam. "10 key points from Labour's election manifesto". RTE.ie.

- Mon; Feb, 03; 2020 - 16:28 (3 February 2020). "Labour: We will build 18,000 homes in one year". Irish Examiner. Retrieved 16 October 2020.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- Hunt, Conor (28 January 2020). "Labour manifesto focuses on rents, housing and health". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Mon; Feb, 03; 2020 - 16:28 (3 February 2020). "Labour: We will build 18,000 homes in one year". Irish Examiner. Retrieved 16 October 2020.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- "Senator O'Riordain calls for legalisation of cannabis". Irish Examiner. Retrieved 24 December 2020.

- Armstrong, Kathy. "'Sick people don't need to be in court' - Senator Aodhán O Riordain backs decriminalising all drugs for personal use". The Irish Independent. Retrieved 24 December 2020.

- O'Toole, Jason. "The Full Hot Press Interview with Labour's Alan Kelly". Hotpress. Retrieved 24 December 2020.

- "Labour Manifesto 2020" (PDF). Labour.ie. Retrieved 24 December 2020.

- "Context: Irish Labour Party Archive". catalogue.nli.ie.

- "Context: Democratic Left Papers". catalogue.nli.ie.

- The Labour Party and the National Labour Party had reunited since the last election. The figures for the Labour party are compared to the two parties combined totals in the previous election.

- "33rd DÁIL GENERAL ELECTION 8 February 2020 Election Results (Party totals begin on page 68)" (PDF). Houses of the Oireachtas. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- "Party Constitution". Labour.ie. 20 May 2009. Retrieved 1 January 2011.

- "Local Elections Results". irishtimes.com. Irish Times. Archived from the original on 29 May 2019.

Further reading

- Paul Daly; Ronan O'Brien; Paul Rouse, eds. (2012). Making the Difference? The Irish Labour Party 1912–2012. Cork: The Collins Press. ISBN 978-1-84889-142-5.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Labour Party (Ireland). |