Joub Jannine

Joub Jannine (Arabic: جب جنين / ALA-LC: Jub Jannīn) is located in the Beqaa Valley in Lebanon.

Joub Jannine, Lebanon | |

Shown within Lebanon | |

| Alternative name | Jeb Jannine |

|---|---|

| Location | Beqaa Valley, Lebanon |

| Coordinates | 33.63°N 35.78°E |

| Part of | Beqaa District |

| History | |

| Periods | Trihedral Neolithic, Heavy Neolithic, Neolithic |

| Site notes | |

| Archaeologists | Henri Fleisch |

| Condition | ruins |

| Public access | Yes |

Joub Jannine is the capital of West Beqaa. It is a town and the center of the Western Beqaa District, hosting the Serail, which is a main governmental building serving the area. Joub Jannine is the largest and most populated town in its district. All major banks exist in Joub Jannine as well as a trades college, Amusement Park, indoor/outdoor soccer arena, basketball court and the weekly Souk which takes place every Saturday and is a local produce market.

Joub Jannine is surrounded by a number of villages. To the south there is the village of Lala, Ghazze to the north, Kamid al lawz to the east, and Kefraya, known for its wine grape vineyards, to the west.[1]

Archaeological sites

Joub Jannine I is a small surface site brought to the surface through erosional activity of a stream. It is 8 km northeast of Qaraoun in a range of foothills, 1 km north of a small village called Jebel Gharbi, between two tracks, west of cote 878 by about 200 m. The site was found by Dubertret with a collection made by Henri Fleisch and Maurice Tallon that is now in the Museum of Lebanese Prehistory at the Saint Joseph University. Flint tools found on the site included bifaces and rough pieces that were suggested to date to the Acheulean.[2][3][4]

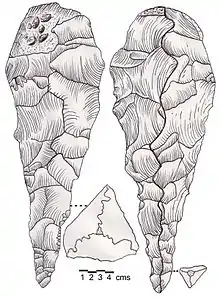

Joub Jannine II was first discovered by M. Billaux in 1957. It was described by Henri Fleisch as Neolithic in 1960.[5] It is located on the right bank of the Litani River northwest of the village, 100 m from the river and 100 m east of cote 861. An abundant amount of flint was collected including nine hundred and forty four tools and one hundred and fifty two cores.[3][6] This was first reported to be a paleolithic industry by Lorraine Copeland and Peter Wescombe.[7] A highly specialized archaeological industry of striking spheroid and trihedral flint tools was found at the site and published by Fleisch in 1960, termed by Copeland and Wescombe as the Trihedral Neolithic.[5] Little has been said about this industry or the ancient people that would have used these huge rock mauls (i.e. hammers) in this area, at the dawn of agriculture, or what they would have been using them for.[8]

The material from Joub Jannine II was described by Lorraine Copeland as

Unique in Lebanon, except for isolated pieces at other sites, and consists of core-tools evidently made for a special purpose. (see Trihedral lithic pictured)[2]

Joub Jannine III (The Gardens) is a Heavy Neolithic site of the Qaraoun culture, 1.5 kilometres (0.93 mi) south of the village along steep slopes and around the houses. It was discovered by Henri Fleisch and Maurice Tallon in 1957. An abundant amount of material was recovered, which included several large flakes and blades along with a finer series of rabots and scrapers that is now held in the Museum of Lebanese Prehistory at the Saint Joseph University. No large bifaces were found at this site. The site may extend through the areas now turned into gardens. It was covered in crops in 1966.[9]

Tourism & Nightlife

Tourism

Joub Jannine is not really known for tourism. However, it is home to one of the oldest bridges in Lebanon, called The Roman Bridge of Joub Jannine (built in 704 AD). Sadly, the bridge collapsed in 1943, but it was rebuilt with the same rocks and is currently identical to the bridge the Romans built. It is located at the entrance of Joub Jannine on Joub Jannine-Chtoura Rd.

Nightlife

Joub Jannine is known for its variety in restaurants and cafes which make it a destination town for most surrounding villages. All restaurants and fast food joints serve Nargila (Shisha).

Nightlife exists but limited due to the towns size and distance from the major cities. Nightlife is limited to some operating cafeterias, bars and restaurants around the town which serve alcoholic drinks and quick bite plates and stay open a little past midnight.

References

- Robert Joseph (1 December 2006). Wine Travel Guide to the World. Footprint Travel Guides. pp. 346–. ISBN 978-1-904777-85-4. Retrieved 30 April 2011.

- L. Copeland; P. Wescombe (1966). Inventory of Stone-Age Sites in Lebanon: North, South and East-Central Lebanon, p. 34-35. Impr. Catholique. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

- Fred Wendorf; Anthony E. Marks (1975). Problems in prehistory: North Africa and the Levant. SMU Press. ISBN 978-0-87074-146-3. Retrieved 30 April 2011.

- Besançon, J. et Hours, F., Préhistoire et géomorphologie : les formes du relief et les dépôts quaternaires dans la région de Joub Jannine (Béqaa méridionale, Liban). Hannon, Beyrouth, vol. V, p. 63-95, 1970

- Fleisch, Henri., Les industries lithiques récentes de la Békaa, République Libanaise, Acts of the 6th C.I.S.E.A., vol. XI, no. 1. Paris, 1960.

- Michael D. Petraglia; Ravi Korisettar (1998). Early human behaviour in global context: the rise and diversity of the Lower Paleolithic Period. Routledge. pp. 254–. ISBN 978-0-415-11763-0. Retrieved 30 April 2011.

- Francis Hours (1989). Hommage à Francis Hours. Maison de l'Orient. Retrieved 30 April 2011.

- Lorraine Copeland; P. Wescombe (1965). Inventory of Stone-Age sites in Lebanon, p. 43. Imprimerie Catholique. Retrieved 21 July 2011.

- Moore, A.M.T. (1978). The Neolithic of the Levant. Oxford University, Unpublished Ph.D. Thesis. pp. 444–446.

External links

- Joub Jannine, Localiban

- Chateau Kefraya Website