Key signature

In Western musical notation, a key signature is a set of sharp (♯), flat (♭), or rarely, natural (♮) symbols placed on the staff at the beginning of a section of music. The initial key signature in a piece is placed immediately after the clef at the beginning of the first line. If the piece contains a section in a different key, the new key signature is placed at the beginning of that section.

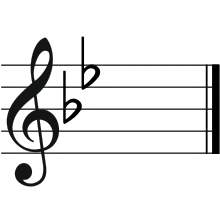

In a key signature, a sharp or flat symbol on a line or space of the staff indicates that the note represented by that line or space is to be played a semitone higher (sharp) or lower (flat) than it would otherwise be played. This applies through the end of the piece or until another key signature is indicated. Each symbol applies to all notes in the same pitch class—for example, a flat on the third line of the treble staff (as in the diagram) indicates that all notes appearing as Bs are played as B-flats. This convention was not universal until the late Baroque and early Classical period—music published in the 1720s and 1730s may have key signatures showing sharps or flats in both octaves for notes which fall within the staff.

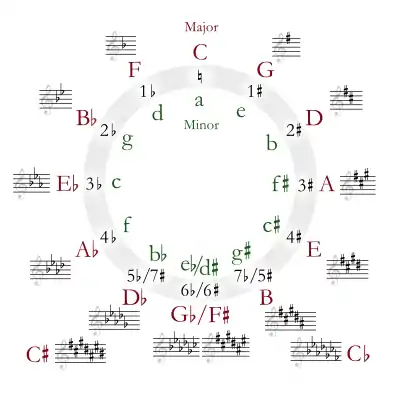

Most of this article addresses key signatures that represent the diatonic keys of Western music. These contain either flats or sharps, but not both, and the different key signatures add flats or sharps according to the order shown in the circle of fifths.

Each major and minor key has an associated key signature, showing up to seven flats or seven sharps, that indicates the notes used in its scale. Music was sometimes notated with a key signature that did not match its key in this way—this can be seen in some Baroque pieces,[1] or transcriptions of traditional modal folk tunes.[2]

Conventions

With any note as a starting point, a certain series of intervals produces a major scale: whole step, whole, half, whole, whole, whole, half. Starting on C, this yields C-D-E-F-G-A-B-C (a C-major scale). There are no sharps or flats in this scale, so the key signature for C has no sharps or flats in it. Starting on any other note requires that at least one of these notes be changed (raised or lowered) to preserve the major scale pattern. These raised or lowered notes form the key signature. Starting the pattern on D, for example, yields D-E-F♯-G-A-B-C♯-D, so the key signature for D major has two sharps—F♯ and C♯. Key signatures indicate that this applies to the section of music that follows, showing the reader which key the music is in, and making it unnecessary to apply accidentals to individual notes.

In standard music notation, the order in which sharps or flats appear in key signatures is uniform, following the circle of fifths: F♯, C♯, G♯, D♯, A♯, E♯, B♯, and B♭, E♭, A♭, D♭, G♭, C♭. Musicians can identify the key by the number of sharps or flats shown, since they always appear in the same order. A key signature with one sharp must show F-sharp,[3] which indicates G major or E minor.

There can be exceptions to this, especially in 20th-century music, if a piece uses an unorthodox or synthetic scale and an invented key signature to reflect that. This may consist of sharps or flats that are not in the usual order, or of sharps combined with flats (e.g., F♯ and B♭). Key signatures of this kind can be found in the music of Béla Bartók, for example.

In a score, transposing instruments will show a different key signature to reflect their transposition but their music is in the same concert key as the other instruments. Percussion instruments with indeterminate pitch will not show a key signature, and timpani parts are sometimes written without a key signature (early timpani parts were sometimes notated with the high drum as "C" and the low drum a fourth lower as "G", with actual pitches indicated at the beginning of the music, e.g., "timpani in D–A"). In polytonal music, where different parts are actually in different keys sounding together, instruments may be notated in different keys.

Notational conventions

The order in which sharps or flats appear in key signatures is illustrated in the diagram of the circle of fifths. Starting the major scale pattern (whole step, whole, half, whole, whole, whole, half) on C requires no sharps or flats. Proceeding clockwise in the diagram starts the scale a fifth higher, on G. Starting on G requires one sharp, F♯, to form a major scale. Starting another fifth higher, on D, requires F♯ and C♯. This pattern continues, raising the seventh scale degree of each successive key. As the scales become notated in flats, this is shown by eliminating one of the flats. This is strictly a function of notation—the seventh scale degree is still being raised by a semitone compared to the previous key in the sequence. Going counter-clockwise from C results in lowering the fourth scale degree with each successive key (starting on F requires a B♭ to form a major scale). Each major key has a relative minor key that shares the same key signature. The relative minor is always a minor third lower than its relative major.

The key signatures with seven flats and seven sharps are usually notated in their enharmonic equivalents. C♯ major (seven sharps) is usually written as D♭ major (five flats) and C♭ major is usually written as B major.

Key signatures can be extended through double sharps and double flats but this is extremely rare. The key of G♯ major can be expressed with a double sharp on F (F![]() ) and single sharps on the other six pitches. As with the seven-sharp and seven-flat examples, the simpler enharmonic key can be used instead (A♭ is enharmonically equivalent with only four flats).

) and single sharps on the other six pitches. As with the seven-sharp and seven-flat examples, the simpler enharmonic key can be used instead (A♭ is enharmonically equivalent with only four flats).

The key signature may be changed at any time in a piece by providing a new signature. If the new signature has no sharps or flats, a signature of naturals, as shown, is used to cancel the preceding signature. If a change in signature occurs at the start of a new line on the page, where a signature would normally appear, the new signature is customarily repeated at the end of the previous line to make the change more conspicuous.

Variants of standard conventions

In traditional use, when the key signature change goes from sharps to flats or vice versa, the old key signature is cancelled with the appropriate number of naturals before the new one is inserted; but many more recent publications (whether of newer music or newer editions of older music) dispense with the naturals (unless the new key signature is C major) and simply insert the new signature.

Similarly, when a signature with either flats or sharps in it changes to a smaller signature of the same type, strict application of tradition or convention would require that naturals first be used to cancel just those flats or sharps that are being subtracted in the new signature before the new signature itself is written; but, again, more modern usage often dispenses with these naturals.

When the signature changes from a smaller to a larger signature of the same type, the new signature is simply written in by itself, in both traditional and newer styles.

At one time it was usual to precede the new signature with a double barline (provided the change occurred between bars and not inside a bar), even if it was not required by the structure of the music to mark sections within the movement; but more recently it has increasingly become usual to use just a single barline. The courtesy signature that appears at the end of a line immediately before a change is usually preceded by an additional barline; the line at the very end of the staff is omitted in this case.

If both naturals and a new key signature appear at a key signature change, there are also more recently variations about where a barline will be placed (in the case where the change occurs between bars). For example, in some scores by Debussy, in this situation the barline is placed after the naturals but before the new key signature. Hitherto, it would have been more usual to place all the symbols after the barline.

The A♯ which is the fifth sharp in the sharp signatures may occasionally be notated on the top line of the bass staff, whereas it is more usually found in the lowest space on that staff. An example of this can be seen in the full score of Ottorino Respighi's Pines of Rome, in the third section, "Pines of the Janiculum" (which is in B major), in the bass-clef instrumental parts.

In the case of seven-flat key signatures, the final F♭ may occasionally be seen on the second-top line of the bass staff, whereas it would more usually appear on the space below the staff. An example of this can be seen in Isaac Albéniz's Iberia: first movement, "Evocación", which is in A♭ minor.

Major scale structure

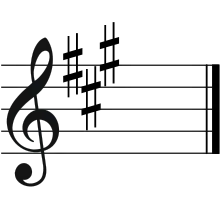

Scales with sharp key signatures

There can be up to seven sharps in a key signature, appearing in this order: F♯ C♯ G♯ D♯ A♯ E♯ B♯.[4][5] The key note or tonic of a piece in a major key is a semitone above the last sharp in the signature.[6] For example, the key of D major has a key signature of F♯ and C♯, and the tonic (D) is a semitone above C♯. Each scale starting on the fifth scale degree of the previous scale has one new sharp, added in the order shown.[5]

| Major key | Number of sharps | Sharp notes | Minor key | Enharmonic equivalent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C major | 0 | – | A minor | None |

| G major | 1 | F♯ | E minor | None |

| D major | 2 | F♯, C♯ | B minor | None |

| A major | 3 | F♯, C♯, G♯ | F♯ minor | None |

| E major | 4 | F♯, C♯, G♯, D♯ | C♯ minor | None |

| B major | 5 | F♯, C♯, G♯, D♯, A♯ | G♯ minor | C♭ major/A♭ minor |

| F♯ major | 6 | F♯, C♯, G♯, D♯, A♯, E♯ | D♯ minor | G♭ major/E♭ minor |

| C♯ major | 7 | F♯, C♯, G♯, D♯, A♯, E♯, B♯ | A♯ minor | D♭ major/B♭ minor |

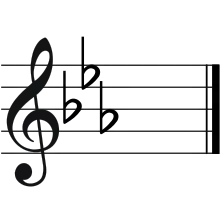

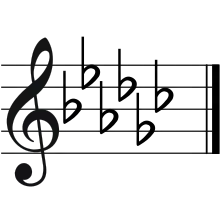

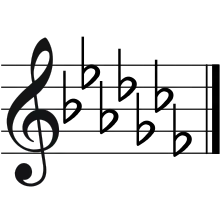

Scales with flat key signatures

There can be up to seven flats in a key signature, applied as: B♭ E♭ A♭ D♭ G♭ C♭ F♭[4][5] The major scale with one flat is F major. In all major scales with flat key signatures, the tonic in a major key is a perfect fourth below the last flat. When there is more than one flat, the tonic is the note of the second-to-last flat in the signature.[6] In the major key with four flats (B♭ E♭ A♭ D♭), for example, the second to last flat is A♭, indicating a key of A♭ major. Each new scale starts a fifth below (or a fourth above) the previous one.

| Major key | Number of flats | Flat notes | Minor key | Enharmonic equivalent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C major | 0 | – | A minor | None |

| F major | 1 | B♭ | D minor | None |

| B♭ major | 2 | B♭, E♭ | G minor | None |

| E♭ major | 3 | B♭, E♭, A♭ | C minor | None |

| A♭ major | 4 | B♭, E♭, A♭, D♭ | F minor | None |

| D♭ major | 5 | B♭, E♭, A♭, D♭, G♭ | B♭ minor | C♯ major/A♯ minor |

| G♭ major | 6 | B♭, E♭, A♭, D♭, G♭, C♭ | E♭ minor | F♯ major/D♯ minor |

| C♭ major | 7 | B♭, E♭, A♭, D♭, G♭, C♭, F♭ | A♭ minor | B major/G♯ minor |

Relationship between key signature and key

Key signatures are a notational device in diatonic or tonal music that define the key and its diatonic scale without the need for accidentals. Music can be notated using other means, and the key of a piece of music may not always conform to the notated key signature. This is particularly true in pre-Baroque music, when the concept of key had not yet evolved to its present state.

More extensive pieces often change key (modulate) during contrasting sections. These sections are sometimes indicated with a change of key signature, but are sometimes indicated using accidentals.

The Toccata and Fugue in D minor, BWV 538 by Bach has a key signature with no sharps or flats, indicating that it may be in D, in the Dorian, but the B♭s that occur in the piece are written with accidentals, making the music actually in D minor.

Additional terminology

Keys which are associated with the same key signature are called relative keys.

When musical modes, such as Lydian or Dorian, are written using key signatures, they are called transposed modes.

Use outside of the Western common-practice period

Key signatures are also used in music that does not come from the Western common-practice-period. This includes folk music, non-Western music, and Western music from before or after the common practice period.

Klezmer music uses scales other than diatonic major or minor, such as Freygish (Phrygian). Because of the limitations of the traditional highland bagpipe scale, key signatures are often omitted from written pipe music, which otherwise would be written with two sharps, F♯ and C♯.[7] (The pipes are incapable of playing F♮ and C♮ so the sharps are not notated.) 20th century composers such as Bartók and Rzewski (see below) experimented with non-diatonic key signatures.

Earlier notation styles

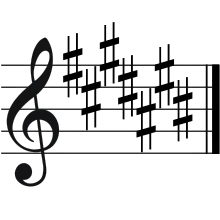

In music from the Baroque period, it is common to see key signatures in which the notes are annotated in a different order from the modern practice, or with the same note-letter annotated for each octave.

Unusual signatures

The 15 key signatures that form diatonic scales are sometimes called standard key signatures. Other scales are written either with a standard key signature and use accidentals as required, or with a nonstandard key signature. Examples of the latter include the E♭ (right hand), and F♯ and G♯ (left hand) used for the С diminished (С octatonic) scale in Bartók's Crossed Hands (no. 99, vol. 4, Mikrokosmos), or the B♭, E♭ and F♯ used for the D Phrygian dominant scale in Frederic Rzewski's God to a Hungry Child.

No sharps or flats in a key signature can indicate that the music is in the key of C major / A minor or that the piece is modal or atonal, and does not have a key signature. An example is Bartók's Piano Sonata, which has no fixed key and is highly chromatic.

If not bound by common practice conventions, microtones can also be notated in a key signature; which microtonal symbols are used depends on the system.

History

The use of a one-flat signature developed in the Medieval period, but signatures with more than one flat did not appear until the 16th century, and signatures with sharps not until the mid-17th century.[8]

When signatures with multiple flats first came in, the order of the flats was not standardized, and often a flat appeared in two different octaves, as shown at right. In the late 15th and early 16th centuries, it was common for different voice parts in the same composition to have different signatures, a situation called a partial signature or conflicting signature. This was actually more common than complete signatures in the 15th century.[9] The 16th-century motet Absolon fili mi by Pierre de La Rue (formerly attributed to Josquin des Prez) features two voice parts with two flats, one part with three flats, and one part with four flats.

Baroque music written in minor keys often was written with a key signature with fewer flats than we now associate with their keys; for example, movements in C minor often had only two flats (because the A♭ would frequently have to be sharpened to A♮ in the ascending melodic minor scale, as would the B♭).

Table

|

See also

References

- Schulenberg, David. Music of the Baroque. New York: Oxford University Press, 2001. p. 72.. "(…) to determine the key of a Baroque work one must always analyze its tonal structure rather than rely on the key signature."

- Cooper, David. The Petrie Collection of the Ancient Music of Ireland. Cork: Cork University Press, 2005. p. 22. "In a few cases Petrie has given what is clearly a modal melody a key signature which suggests that it is actually in a minor key. For example, Banish Misfortune is presented in D minor, although it is clearly in the Dorian mode."

- "How to Read Key Signatures".

- Bower, Michael. 2007. "All about Key Signatures Archived 2010-03-11 at the Wayback Machine". Modesto, CA: Capistrano School (K–12) website. (Accessed 17 March 2010).

- Jones, George Thaddeus. 1974. Music Theory: The Fundamental Concepts of Tonal Music Including Notation, Terminology, and Harmony, p.35. Barnes & Noble Outline Series 137. New York, Hagerstown, San Francisco, London: Barnes & Noble. ISBN 978-0-06-460137-5.

- Kennedy, Michael. 1994. "Key-Signature". Oxford Dictionary of Music, second edition, associate editor, Joyce Bourne. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-869162-9.

-

Nienhuys, Han-Wen; Nieuwenhuizen, Jan (2009). "GNU LilyPond — Notation Reference". 2.6.2 Bagpipes. Retrieved 2010-03-28.

Bagpipe music nominally uses the key of D Major (even though that isn’t really true). However, since that is the only key that can be used, the key signature is normally not written out.

- "Key Signature", Harvard Dictionary of Music, 2nd ed.

- "Partial Signature", Harvard Dictionary of Music, 2nd ed.