Music engraving

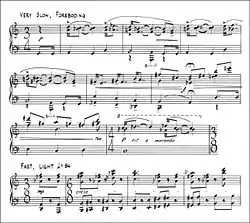

Music engraving is the art of drawing music notation at high quality for the purpose of mechanical reproduction. The term music copying is almost equivalent—though music engraving implies a higher degree of skill and quality, usually for publication. The name of the process originates in plate engraving, a widely used technique dating from the late sixteenth century.[1] The term engraving is now used to refer to any high-quality method of drawing music notation, particularly on a computer ("computer engraving" or "computer setting") or by hand ("hand engraving").

Traditional engraving techniques

Elements of music engraving style

Mechanical music engraving began in the middle of the fifteenth century. As musical composition increased in complexity, so too did the technology required to produce accurate musical scores. Unlike literary printing, which mainly contains printed words, music engraving communicates several different types of information simultaneously. To be clear to musicians, it is imperative that engraving techniques allow absolute precision. Notes of chords, dynamic markings, and other notation line up with vertical accuracy. If text is included, each syllable matches vertically with its assigned melody. Horizontally, subdivisions of beats are marked not only by their flags and beams, but also by the relative space between them on the page.[1] The logistics of creating such precise copies posed several problems for early music engravers, and have resulted in the development of several music engraving technologies.

Movable type

Similar to book printing, music printing began in the fifteenth century with the use of movable type. The central problem posed to early music engravers using moveable type was the proper integration of notes, staves, and text. Often, staff lines were hand drawn prior to printing, or added to the printed music afterward. Ottavio Petrucci, one of the most innovative music printers working at the turn of the sixteenth century, used a triple impression technique that printed staves, text, and notes in three separate steps.[1]

Plate engraving

Although plate engraving had been used since the early fifteenth century for creating visual art and maps, it was not applied to music until 1581.[1] In this method, a mirror image of a complete page of music was engraved onto a metal plate. Ink was then applied to the grooves, and the music print was transferred onto paper. Metal plates could be stored and reused, which made this method an attractive option for music engravers. Copper was the initial metal of choice for early plates, but by the eighteenth century pewter became the standard material due to its malleability and lower cost.[2]

At first, plates were engraved freely by hand. Eventually, music engravers developed a number of tools to aid in their process, including:

- Scorers for staves and bar lines, the use of which inspired the term musical score

- Elliptical gravers for crescendos and diminuendos

- Flat gravers for ties and ledger lines

- Punches for note heads, clefs, accidentals, and letters[3]

Plate engraving was the methodology of choice for music printing until the late nineteenth century, at which point its decline was hastened by the development of photographic technology.[1] Nevertheless, the technique has survived to the present day, and is still occasionally used by select publishers such as G. Henle Verlag in Germany.[4]

Hand copying

Historically, a musician was required to draw his own staff lines (staves) onto blank paper. Eventually, staff paper was manufactured pre-printed with staves as a labor-saving technique. The musician could then write music directly onto the lines in pencil or ink.

In the twentieth century, music staff paper was sometimes printed on vellum or onionskin—a durable, semi-transparent material that made it easier for the musician to correct mistakes and revise the work, and also made it possible to reproduce the manuscript through the ozalid process. Also at this time, a music copyist was often employed to hand-copy individual parts (for each performer) from a composer's full score. Neatness, speed, and accuracy were desirable traits of a skilled copyist.

Other techniques

- Lithography: Similar to metal plate engraving, the music was etched onto limestone and then burned onto the surface with acid to preserve the stone plates for future use.[5]

- Stencils, stamps, and dry transfers, including the Notaset, a system inspired by the Letraset used in the twentieth century.[6] Brushing ink through stencils was a high-quality technique used by Amersham-based company Halstan & Co.

- Music typewriters: Originally developed in the late nineteenth century, this technology did not become popular until the mid-1900s. The machines required the use of pre-printed manuscript paper.[7] This technique produced low-quality results and was never widely used.[8]

Computer music engraving

With the advent of the personal computer since the 1980s, traditional music engraving has been in decline, as it can now be accomplished by computer software designed for this purpose. There are various such programs, known as scorewriters, designed for writing, editing, printing and playing back music, though only a few produce results of a quality comparable to high-quality traditional engraving. Scorewriters have many advanced features, such as the ability to extract individual parts from an orchestral/band score, to transcribe music played on a MIDI keyboard, and conversely to play back notation via MIDI.

Beginning in the 1980s, WYSIWYG software such as Sibelius, Mozart, MuseScore, and Finale first let musicians enter complex music notation on a computer screen, displaying it just as it will look when eventually printed. Such software stores the music in files of proprietary or standardized formats, usually not directly readable by humans.

Other software, such as GNU LilyPond and Philip's Music Writer, reads input from ordinary text files whose contents resemble a computer macro programming language that describes bare musical content with little or no layout specification. The software translates the usually handwritten description into fully engraved graphical pages to view or send for printing, taking care of appearance decisions from high level layout down to glyph drawing. The music entry process is iterative and is similar to the edit-compile-execute cycle used to debug computer programs.

Beside ready-made applications there are also some programming libraries for music engraving, such as Vexflow (Javascript library), Verovio (C++, Javascript and Python), Guido Engine (C++ library), and Manufaktura Controls (.NET libraries). The main purpose of these libraries is to reduce time required for development of software with score rendering capabilities.

Overview of music engraving libraries divided by programming languages

| Language/Platform | Non-commercial | Commercial |

|---|---|---|

| C++ | Belle Bonne Sage, Guido Engine, Verovio | |

| HTML/Javascript | Verovio, Vexflow | |

| Java | Verovio | |

| .NET Framework | PSAM Control Library | Manufaktura Controls |

| Python | Verovio | |

| various platforms | SeeScore library |

See also

References

- King, A. Hyatt (1968). Four Hundred Years of Music Printing. London: Trustees of the British Museum.

- Wolfe, Richard J. (1980). Early American Music Engraving and Printing. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press.

- Calderisi, Maria (1981). Music Publishing in the Canadas, 1800-1867. Ottawa: National Library of Canada.

- "Music Engraving". G. Henle Publishers. Archived from the original on December 30, 2017. Retrieved November 3, 2014.

- "About Lithography". Music Printing History. Retrieved November 3, 2014.

- "Transfers". Music Printing History. Retrieved November 3, 2014.

- "Music Typewriters". Music Printing History. Retrieved October 22, 2017.

- "Machine Types Simplified Music." Popular Science, August 1948, p. 143.

Further reading

- Elaine Gould. Behind Bars: The Definitive Guide to Music Notation Faber Music Ltd, London.

- Ted Ross. Teach Yourself The Art of Music Engraving & Processing Hansen Books, Florida.

- Clinton Roemer. The Art of Music Copying: The Preparation of Music for Performance. Roerick Music Co., Sherman Oaks, California.

External links

- Musical Engraving on Metal Plates: a Traditional Craft Demonstrated (video documentary in German and English)