Krazy Kat Klub

The Krazy Kat Klub—also known as The Kat[2] and Throck's Studio[3]—was an iconic Bohemian cafe, speakeasy, and nightclub in Washington, D.C. during the historical era known as the Jazz Age.[3][4] The back-alley establishment was founded by portraitist and scenic designer Cleon "Throck" Throckmorton.[5][6] The speakeasy was founded after the passage of the Sheppard Bone-Dry Act by the U.S. Congress that imposed a ban on alcoholic beverages in the District of Columbia.[7][8]

"The Kat" | |

Clientele arriving at the Krazy Kat in 1921 | |

| |

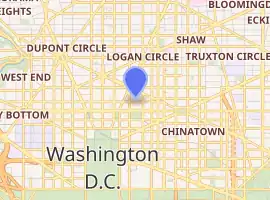

| Address | 3 Green Court Washington, D.C. United States |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 38.904°N 77.031°W |

| Owner | John Don Allen, John Stiffen & Cleon Throckmorton[1] |

| Opened | 1919 |

| Closed | 1926? |

The Kat's free-spirited denizens were known for their unapologetic embrace of free love ("unrestricted impulse").[3] The club's name was derived from the androgynous title character of a comic strip that was popular at the time,[3][9] and this namesake purportedly communicated that the venue was inclusive towards clientele of all sexual persuasions.[9][6][10] Consequently, the secluded venue "served as a rendezvous spot for D.C.'s early gay community"[10] and was frequented by gay patrons such as Jeb Alexander who could meet "with like-minded persons" without fear of exposure.[6][11]

Contemporary sources alleged that, during the second term of President Woodrow Wilson's administration, the club's habitués included employees of the federal government as well as possibly members of the U.S. Congress.[12][1][13] Today, the club's neighborhood is now the site of The Green Lantern, a D.C. gay bar.[10]

Location

The establishment was located at No. 3 Green Court near Washington, D.C.'s Thomas Circle in an economically-depressed area contemporaneously referred to as "the Latin Quarter."[2][4] The Krazy Kat Klub's inconspicuous entrance was in a narrow alley that led out to Massachusetts Avenue.[6] During 1921, the entrance door bore a rectangular hand-painted sign that read "Syne of Ye Krazy Kat" [sic] and featured a black cat that resembled Krazy Kat being hit by a brick.[14][9] A chalk-inscribed message adorned the top of the door that warned: "All soap abandon ye who enter here!"[14][6] The club's open hours were advertised as "9 p.m. to 12:30."[2]

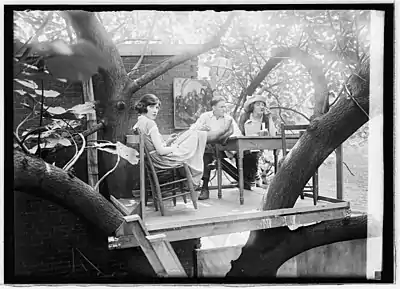

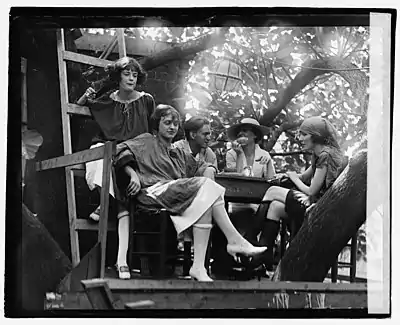

The club's unphotographed indoor dining area was situated on a second-floor of an old livestock stable.[12] Upon entering from the alleway, one crossed "a lumber-littered room" and ascended a "narrow winding staircase" to reach "a smoke-filled, dimly lighted room that was fairly well filled with laughing, noisy people, who seemed to be having just the best time in the world, with no one to see and no one to care who saw."[12] The ramshackle venue was described as rife with cobwebs and had "futurist pictures on the walls, small wooden tables, rickety chairs, and candles for light."[12][1] The club's premises included both an indoor dance floor and an outdoor courtyard for al fresco dining and art exhibitions. The courtyard featured a small rustic tree-house (pictured), accessible via a wooden twelve-step ladder.[3][15]

History

In 1917, the controversial passage of the Sheppard Bone-Dry Act directly led to the closure of 267 barrooms and nearly 90 whole establishments in the District of Columbia.[7] Over 2,000 employees in D.C. barrooms and wholesale establishments were thrown out of work, and the district lost nearly half-a-million per year in tax revenues.[7] In the wake of this draconian bill, underground speakeasies such as the Krazy Kat Klub flourished.[8]

The Kat was purportedly owned by John Don Allen, John Stiffen, and artist Cleon Throckmorton.[1] The venue was founded circa 1919 by Throckmorton after he had completed his further studies at George Washington University.[5][17] Throckmorton was a pre-Raphaelite impressionist who believed that devoted artists should pursue their vocation both day and night by surrounding themselves with appropriate settings.[2] A frequent habitué of The Kat was Throckmorton's first wife Katherine Mullen—a model and sketch artist—who was also known for her radio performances as a singer and ukulele player with the Crandall Saturday Nighters.[3][18]

Due to its courtyard and tree-house, the establishment was envisioned as an idyllic haunt for free-wheeling bohemians, flappers, and other "young moderns" during the incipient Jazz Age.[3] By 1920, the club was already renowned for its riotous live performances of hot jazz music which occasionally degenerated into mayhem.[19]

A crime reporter for The Washington Post described the Krazy Kat Klub as being "something like a Greenwich Village coffee house," featuring "gaudy pictures created by futurists and impressionists."[1][6] According to the Washington City Paper, The Kat clandestinely functioned as a nexus for Washington, D.C.'s "early gay community."[10] The transgressive venue was mentioned in the secret personal diary of gay Washington, D.C. resident Jeb Alexander, who wrote that the inclusive[9] club was a "Bohemian joint in an old stable up near Thomas Circle . . . [a gathering place for] artists, musicians, atheists (and) professors."[6][11] Writer Victor Flambeau described the club in a February 1922 article for The Washington Times:

[A] hidden haunt where one might find in comradeship those divine, congenial devils, art inspired and mad, no doubt, who have renounced the commercial world with its seductive wealth, to gain in solitude or blithe companionship another kind of wealth and fame in self-expression.... When the hours wane, and the candles burn low, and the big fire glows, and over the cigarettes and the cider, the coffee and sandwiches, what do they chat of, these men and women, boys and girls, the would-be writers, painters, poets of tomorrow?"[3]

According to Throckmorton himself, the avant-garde venue "proved not only a club for artists, but a source of supply for musicians and playwrights," and he claimed that several plays were written on its premises.[3][2] Flambeau noted that, by 1922, "in imitation of the Krazy Kat, other bohemian restaurants sprang up in Washington to supply the demand" such as the Silver Sea Horse and Carcassonne in Georgetown.[3][12] Over time, The Kat became one of the most vogue locations for Washington's intelligentsia and aesthetes to congregrate.[2]

During its tumultuous half-decade existence, The Kat was declared to be a "disorderly house" by municipal authorities and was raided by the metropolitan police on several occasions during the Prohibition period.[13][1] One particular raid in February 1919 reportedly interrupted a violent brawl inside the club, during which a shot was fired.[1] The surprise raid resulted in the arrests of 25 krazy kats—22 men and 3 women—described in a Washington Post report of February 22nd as "self-styled artists, poets and actors."[1][13] The article specifically noted that several arrested patrons "worked for the [federal] government by day and masqueraded as Bohemians by night."[1][13]

The club presumably closed at some time prior to 1928 when Throckmorton relocated to Hoboken, New Jersey.[17] During this same period, Throckmorton divorced his first wife (and model) Katherine Mullen and subsequently married screen actress Juliet Brenon,[22] the niece of Irish-American motion picture auteur Herbert Brenon who directed the first cinematic adaptation of The Great Gatsby (1926).[17][23][24][25] Throckmorton would later become one of the most prolific scenic designers for Broadway plays, and his Greenwich Village apartment that he shared with Juliet Brenon would become an after-hours salon for thespians, artists, and intellectuals such as Noël Coward, Norman Bel Geddes, Eugene O'Neill and E.E. Cummings.[17][23] Their politically leftward salon would notably raise funds for the Republican faction during the Spanish Civil War.[17]

Gallery

Cleon, Katherine, and others arrive at the back-alley entrance of The Kat

Cleon, Katherine, and others arrive at the back-alley entrance of The Kat Another angle of guests arriving at the entrance of The Krazy Kat Klub

Another angle of guests arriving at the entrance of The Krazy Kat Klub A model, presumably Katherine Mullen,[3] poses for Cleon

A model, presumably Katherine Mullen,[3] poses for Cleon Cleon Throckmorton and his wife Katherine Mullen relaxing with a friend

Cleon Throckmorton and his wife Katherine Mullen relaxing with a friend Cleon, Katherine, and others chat over coffee and cigarettes

Cleon, Katherine, and others chat over coffee and cigarettes A waiter ascends a ladder to serve patrons in the club's tree-house

A waiter ascends a ladder to serve patrons in the club's tree-house

See also

References

Citations

- The Washington Post 1919.

- The Washington Herald 1921.

- Flambeau 1922.

- Farmer 2012.

- The Washington Times 1921.

- InTowner 2009.

- The Washington Times 1917.

- The Sunday Star 1927.

- Bellot 2017.

- Baek 2014.

- Alexander 1993.

- Kebler 1919.

- MessyNessy 2012.

- Library of Congress LC-F8-15145.

- Library of Congress LC-F81-15101.

- Alderman 2020.

- The New York Times 1965.

- The Evening Star 1925.

- The Washington Times 1920.

- The Flapper Magazine 1922.

- The New York Times 1922.

- The New York Times 1927.

- The New York Times 1979.

- Ditta 2018.

- Green 1926.

Sources

- Alderman, Tim (May 2, 2020). "Gay History: A Gay Old Kat". timalderman.com. Retrieved October 4, 2020.

The clientele included college kids, flappers and gays.... The club was named after the comic strip Krazy Kat (who can be seen on the door sign in the photo above). Krazy was the first androgynous hero(ine) of the comics: sometimes Krazy was a he, sometimes a she. As creator George Herriman stated, Krazy was willing to be either.

CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Alexander, Jeb (1993). Russell, Ina (ed.). Jeb and Dash: A Diary of Gay Life 1918-1945. Faber & Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-19847-4. Retrieved October 4, 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Antics of Musicians Makes Jazz Foolish, M.D. Says in Letter: Krazy Kat Klub Disrupted". The Washington Times. Washington, D.C. November 16, 1920. Retrieved October 4, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

War casualties during the jazz outbursts have been too numerous to mention. Harsh rumor has it that the Krazy Kat Klub and other choice back alley enterprises have been disrupted as a result of rude un-Bohemian cacophanations.

- "Army-Navy Game To Be Broadcast: 'Saturday Nighters' Featured". The Evening Star. Washington, D.C. November 28, 1925. p. 38. Retrieved October 10, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

...Katherine Throckmorton, songs with ukulele...

- Baek, Raphaella (January 24, 2014). "Did Washington's gay bars open as gay bars?". Washington City Paper. Washington, D.C. Retrieved October 4, 2020.

In the early 20th century, a speakeasy treehouse called Krazy Kat Klub operated right across from the present-day Green Lantern, at what was then No. 3 Green Court, and served as a rendezvous spot for D.C.'s early gay community.

CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Bellot, Gabrielle (January 19, 2017). "The Gender Fluidity of Krazy Kat". The New Yorker. New York City. Retrieved October 4, 2020.

In an era when books depicting homosexuality and gender nonconformity could lead to charges of obscenity, 'Krazy Kat,' Tisserand notes, featured a gender-shifting protagonist who was in love with a male character.... A well-known bohemian bar in Washington, D.C., that welcomed queer customers seemed to acknowledge the strip’s anarchic queerness by naming itself Krazy Kat.

CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - "Cleon Throckmorton, 68, Dead; Designed O'Neill Stage Settings". The New York Times. New York City. October 25, 1965. p. 37. Retrieved October 4, 2020.

- Ditta, Joseph (February 16, 2018). "Guide to the Aileen St. John-Brenon Papers (1920-1947 )". New-York Historical Society Museum & Library. Retrieved October 4, 2020.

Aileen's grandfather was the English dramatic critic Edward St. John-Brenon. Her uncle, Herbert Brenon (1880–1958), was a motion picture director perhaps best known for the silent films Peter Pan (1924) and Beau Geste (1926). Aileen's younger sister, Juliet St. John-Brenon (1895–1979), was an actress who appeared in some of their Uncle Herbert's films. Juliet married well-known set designer Cleon "Throck" Throckmorton (1897-1965), who maintained an active studio in bohemian Greenwich Village.

CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - "Engagements: Brenon–Throckmorton". The New York Times. New York City. May 1, 1927. p. 75. Retrieved October 8, 2020.

Mrs. Algernon St. John Brenon of the Hotel Iroquois has announced the engagement of her younger daughter, Miss Juliet Brenon, to Cleon Throckmorton of Washington, D.C., and this city. Miss Brenon is the daughter of the late A. St. John Brenon, who was well known in New York and Europe as a music critic.

- Farmer, Liz (November 21, 2012). "Historic preservation expert Paul Williams on the Krazy Kat Klub". Washington Examiner. Washington, D.C. Retrieved October 4, 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Flambeau, Victor (February 5, 1922). "Flambeau Finds Washington's Bohemia In Hidden Haunt Where Cleon Throckmorton Stages His First Exhibition" (PDF). The Washington Times (Sunday ed.). p. 7. Retrieved October 4, 2020 – via Library of Congress.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Flappers Flaunt Fads in Footwear: Stockings Scare Dogs". The New York Times. New York City. January 29, 1922. p. 34. Retrieved October 4, 2020.

- Green, Abel (November 24, 1926). "Film Review: The Great Gatsby". Variety. Los Angeles, California. Retrieved October 8, 2020 – via Internet Archive.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Has Washington Genuine Art Colony, Asks Scientist: Visits Krazy Kat". The Washington Herald. Washington, D.C. July 31, 1921. Retrieved October 4, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Juliet B. Throckmorton". The New York Times. New York City. November 22, 1979. p. D13. Retrieved October 4, 2020.

- Kebler, Lyman F. (March 3, 1919). "Camouflaged". The Washington Times. Washington, D.C. p. 15. Retrieved October 4, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Krazy Kat (LC-F8-15145)". Library of Congress. Washington, D.C. 1921. LCCN 2016831001. Retrieved October 8, 2020.

- "Krazy Kat, 7/15/21 (LC-F81-15101)". Library of Congress. Washington, D.C. July 15, 1921. LCCN 2016845558. Retrieved October 10, 2020.

- "Many Jobless If District Goes Dry: Passage of Sheppard Bill by House Will Throw Many Out of Work". The Washington Times. Washington, D.C. January 11, 1917. p. 11. Retrieved October 10, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Row In Krazy Kat Lands 14 In Jail: Carefree Bohemians Start Rough-House and Cop Raids Rendezvous". The Washington Post. Washington, D.C. February 22, 1919. p. 5. Retrieved October 4, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Scenes from the Past... Fun During Prohibition at Thomas Circle's Krazy Kat Club & Speakeasy". The InTowner. June 14, 2009. Retrieved October 4, 2020.

- "The 1920s Speakeasy Club with a Treehouse in the Backyard". MessyNessy. July 4, 2012. Retrieved October 4, 2020.

- "Throckmorton Scenic Artist of Real Skill". The Washington Times (Sunday ed.). Washington, D.C. December 11, 1921.

Cleon Throckmorton, well known Washingtonian and founder of the Crazy Kat Restaurant, is rapidly acquiring a reputation as a scene designer of parts through his association with the Provincetown Players of New York.

- "Shirking Charged to Officials Here: Service League Head Claims Sheppard Act Is Being Ignored in District". The Sunday Star. Washington, D.C. November 6, 1927. p. 5. Retrieved October 10, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- "The Psychology of Knees". The Flapper Magazine. June 1922. Retrieved October 4, 2020.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Krazy Kat Klub. |

- "Flambeau Finds Washington's Bohemia In Hidden Haunt", The Washington Times, February 5, 1922.

- "Scenes from the Past... Fun During Prohibition at Thomas Circle's Krazy Kat Club & Speakeasy", The InTowner, June 14, 2009.

- "The 1920s Speakeasy Club with a Treehouse in the Backyard", MessyNessy, July 4, 2012.