The Great Gatsby (1926 film)

The Great Gatsby is a 1926 American silent drama film directed by Herbert Brenon.[1] It is the first film adaptation of the 1925 novel of the same name by F. Scott Fitzgerald. Warner Baxter portrayed Jay Gatsby and Lois Wilson as Daisy Buchanan.[2]

| The Great Gatsby | |

|---|---|

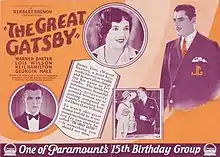

1926 Lobby card | |

| Directed by | Herbert Brenon Ray Lissner (assistant) |

| Produced by | Jesse L. Lasky Adolph Zukor |

| Written by | Becky Gardiner (scenario) Elizabeth Meehan (adaptation) |

| Based on | The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald |

| Starring | Warner Baxter Lois Wilson Neil Hamilton Georgia Hale William Powell |

| Cinematography | Leo Tover |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Paramount Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 80 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | Silent (English intertitles) |

The film was produced by Famous Players-Lasky, and distributed by Paramount Pictures. The Great Gatsby is now considered lost.[3][4] A vintage movie trailer displaying short clips of the film still exists.

Plot

An adaptation of F. Scott Fitzgerald's Long Island-set novel, where Midwesterner Nick Carraway is lured into the lavish world of his neighbor, Jay Gatsby. Soon enough, however, Carraway will see through the cracks of Gatsby's nouveau riche existence, where obsession, madness, and tragedy await.

Cast

- Warner Baxter as Jay Gatsby

- Lois Wilson as Daisy Buchanan

- Neil Hamilton as Nick Carraway

- Georgia Hale as Myrtle Wilson

- William Powell as George Wilson

- Hale Hamilton as Tom Buchanan

- Carmelita Geraghty as Jordan Baker

- George Nash as Charles Wolf[lower-alpha 1]

- Eric Blore as Lord Digby

- Gunboat Smith as Bert

- Claire Whitney as Catherine

- Claude Brooke - Uncredited role

- Nancy Kelly - Uncredited role

Production

The screenplay was written by Becky Gardiner and Elizabeth Meehan and was based on Owen Davis' stage play treatment of The Great Gatsby. The play, directed by George Cukor, opened on Broadway at the Ambassador Theatre on February 2, 1926. Shortly after the play opened, Famous Players-Lasky and Paramount Pictures purchased the film rights for $45,000.[5]

The film's director Herbert Brenon designed The Great Gatsby as lightweight, popular entertainment, playing up the party scenes at Gatsby's mansion and emphasizing their scandalous elements. The film had a running time of 80 minutes, or 7,296 feet.[1][3]

Reception

Fitzgeralds

Reportedly, F. Scott Fitzgerald and his wife Zelda Sayre loathed Brenon's adaptation of his novel and walked out midway through a viewing of the film at a theater.[6] "We saw The Great Gatsby at the movies," Zelda later wrote to an acquaintance. "It's rotten and awful and terrible and we left."[6]

Film critics

Mordaunt Hall—The New York Times' first regular film critic—wrote in a contemporary review that the film was "good entertainment, but at the same time it is obvious that it would have benefited by more imaginative direction."[7] He lamented that Herbert Brenon's direction lacked subtlety and that none of the actors convincingly developed their characters.[7] He faulted a scene where Daisy gulps absinthe: "She takes enough of this beverage to render the average person unconscious. Yet she appears only mildly intoxicated, and soon recovers."[7] Hall also describes a scene in which Gatsby "tosses twenty-dollar gold pieces into the [swimming pool] water, and you see a number of the girls diving for the coins. A clever bit of comedy is introduced by a girl asking what Gatsby is throwing into the water, and as soon as this creature hears that they are real gold pieces she unhesitatingly plunges into the pool to get a share. Gatsby appears to throw the money into the water with a good deal of interest, whereas it might perhaps have been more effective to have him appear a little bored as he watched the scramble of the men and women."[7]

In contrast to Hall's mixed review, journalist Abel Green's November 1926 review published in Variety was more positive.[8] Green deemed Brenon's production to be "serviceable film material" and "a good, interesting gripping cinema exposition of the type certain to be readily acclaimed by the average fan, with the usual Long Island parties and the rest of those high-hat trimmings thrown in to clinch the argument."[8] The Variety reviewer observed that Gatsby's "Volstead violating" bootlegging was not "a heinous crime despite the existence of a federal statute which declares it so."[8] The reviewer praised Warner Baxter's portrayal of Gatsby and Neil Hamilton's portrayal of Nick Carraway but found Lois Wilson's interpretation of Daisy to be needlessly unsympathetic.[8]

Civic groups

Following the release of the film, women's civic groups—such as the Better Films Board of the Women's Council—lodged letters of protest to the studio and producers in December 1926.[9] The women objected that the film depicted Daisy Buchanan having sexual relations with Gatsby prior to marriage and that Tom Buchanan was shown engaging in extramarital sex with Myrtle.[9]

The civic group declared that, although "some homes are not sacred, some women not pure and some men not clean," it was nonetheless morally wrong "in the name of amusement to portray stories of this undesirable life, to hold it up before the theater going public for the [morally] weak to become interested in."[9] They demanded that future motion pictures depict "the decent, clean American life, which if our nation is to stand, must remain clean and decent as it was at the beginning of our Republic."[10]

Preservation status

Professor Wheeler Winston Dixon, the James Ryan Professor of Film Studies at the University of Nebraska, Lincoln made extensive but unsuccessful attempts to find a surviving print. Dixon noted that there were rumors that a copy survived in an unknown archive in Moscow but dismissed these rumors as unfounded.[3] However, the trailer has survived and is one of the 50 films in the three-disc, boxed DVD set More Treasures from American Film Archives, 1894-1931 (2004), compiled by the National Film Preservation Foundation from five American film archives. The trailer is preserved by the Library of Congress (AFI/Jack Tillmany collection) and has a running time of one minute.[3] It was featured on the Blu-ray released by Warner Home Video of director Baz Luhrmann's 2013 adaptation of The Great Gatsby as a special feature.

Gallery

Behind-the-scenes photo of actress Lois Wilson with director Herbert Brenon

Behind-the-scenes photo of actress Lois Wilson with director Herbert Brenon A 1926 lobby card for the film

A 1926 lobby card for the film

References

Notes

- In this silent version, Jay Gatsby's business associate Meyer Wolfsheim is changed to a White Anglo-Saxon Protestant and rechristened Charles Wolf.

Citations

- Library of Congress 2017.

- Tredell 2007, p. 96.

- Dixon 2003.

- Silent Era 2010.

- Tredell 2007, pp. 94–96.

- Howell 2013.

- Hall 1926.

- Green 1926.

- MPPDA Records 1926, p. 1.

- MPPDA Records 1926, p. 2.

Bibliography

- Green, Abel (November 24, 1926). "The Great Gatsby". Variety. Retrieved January 7, 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hall, Mordaunt (November 22, 1926). "Gold and Cocktails". The New York Times. Retrieved January 7, 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Howell, Peter (May 5, 2013). "Five Things You Didn't Know About The Great Gatsby". The Star. Toronto. Retrieved July 5, 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "The Great Gatsby / Herbert Brenon". Performing Arts Encyclopedia. The Library of Congress. January 1, 2017. Retrieved January 7, 2019.

- "Progressive Silent Film List: The Great Gatsby". SilentEra.com. May 6, 2010. Retrieved January 7, 2019.

- Tredell, Nicolas, ed. (2007). Fitzgerald's The Great Gatsby: A Reader's Guide. A & C Black. pp. 94–96. ISBN 978-0-826-49011-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dixon, Wheeler Winston (2003). "The Three Film Versions of The Great Gatsby: A Vision Deferred". Literature Film Quarterly. Archived from the original on June 5, 2013. Retrieved March 9, 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "The Great Gatsby (1926) - Production Code Administration Records". Margaret Herrick Library Digital Collections. Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. December 15, 1926. p. 1. Retrieved March 29, 2020.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to The Great Gatsby (1926 film). |