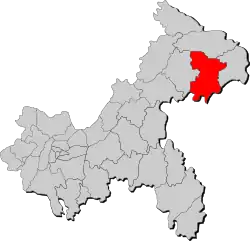

Kuizhou

Kui Prefecture, Kuizhou Circuit, or Kuizhou (Chinese: 夔州; pinyin: Kuízhōu; Wade–Giles: K'uei-chou) was initially established in 619 CE, as a renaming of the existing Xin Prefecture. Kuizhou was an important area from the beginning and through the end of the Tang Dynasty of China, when it was alternatively part of several of the Circuits which made up typical large scale political structural organizations of the Tang era. Kuizhou continued as a political entity through the end of the Song Dynasty, during which it was of Provincial level, a typical large scale political organization of Song era (and later). Kui Prefecture was located in what is now eastern Chongqing. During the Song Dynasty, Kuizhou's capital was located in what is now Fengjie County, Chongqing, and the extent of the province was to what today includes Chongqing, eastern Sichuan, and Guizhou. Part of the importance of Kuizhou was related to its prominent location along the Yangzi River. Kui was also known for its spectacular scenerary, and being a location in which exiled poets wrote their laments.

Geography

Kuizhou (Kui Prefecture) was located in the Three Gorges area of the Yangzi River, a main transportation east-west corridor through China, which made use of the Yangzi River for transportation by water.

History

Kui Prefecture (Kuizhou) was an area typical of many in the southern part of the Tang Empire which experienced an increase in population and development as a result of the disasters beginning with and following the An Lushan Rebellion (also known as the Anshi disturbances). Later, toward the end of the Tang Dynasty this area which was formerly a refuge became itself the center of military activity leading to the breakup of the Tang Imperial Dynasty and the development of the independent states of the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period.

Early background

The Kuizhou area was held by the Han dynasty. During this time, it was known as Baidi, or White Emperor, in English. A poetic tradition developed in Tang and later times of referencing Kuizhou by mentioning Baidi (Murck, 271). However, the area was only on the fringe of the Han empire, and after the fall of the Han dynasty long remained outside of the main area of Chinese culture. Historical records are incomplete.

Early military operations

At the founding of the Tang empire, Kui Prefecture was known as Xin Prefecture (信州, or Xinzhou). Li Xiaogong (formerly the Duke of Zhao Commandery and Emperor Gaozu's distant nephew) was the Tang general assigned there as commandant, after having helped establishing the Tang dynasty in 618. Other famous people connected with political and military events in the history of Kui Prefecture include Tang General Li Jing, who was sent there by Emperor Tang Gaozu, in 619, in order to pursue military operations versus Xiao Xian of Liang and the Eastern Turkic Khaganate. The Tang forces led by Li Jing were unsuccessful in their attempted invasion, being both beset by "bandits" and being turned back at the heavily defended border of the neighboring empire. And in spring 620, Ran Zhaoze (冉肇則) the leader of the Kaishan Tribe (開山蠻), rebelled against Tang rule and attacked Kui Prefecture. When the imperial relative Li Xiaogong fought Ran, he was initially unsuccessful, but Li Jing reinforced him with 800 men and defeated and killed Ran, reconsolidating Kui Prefecture into the area of Tang imperial control.

Outskirts of Tang empire and place of exile

Later, Di Zhixun, father of Di Renjie, born 630, served as prefect of Kui Prefecture. Di Renjie was one of the officials from parts of China which were not the traditional areas for recruitment of top leadership positions which Wu Zetian promoted, during her interregnum. He served her twice as chancellor.

In about 787, imperial chancellor Qi Ying was demoted and exiled to Kui Prefecture, as prefect, by Emperor Tang Dezong.

Zhu Pu, who twice served as imperial chancellor for Emperor Tang Zhaozong (867 – 904, and the second-to-last Tang dynasty emperor), was demoted and exiled sent into exile to serve as military advisor in Kui Prefecture, in 897.

Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms era

The Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms was an era of disunity in the time stretch between the end of the Tang dynasty and the establishment of the Song dynasty: during this period, the political, social, and population center of China moved increasingly toward the south, and during this process Kuizhou came to be more and more central in these regards. Pivotally positioned along and between the upper and lower Yangzi River areas and athwart this major travelway, Kuizhou several of the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms states successively held Kuizhou as a key territorial possession, including Former Shu, Later Tang, Jingnan (also known as Nanping), and Later Shu.

During the Later Tang, Kuizhou was part of Meng Zhixiang's political breakaway, which eventually resulted in the formation of the Later Shu state. During this time Kuizhou was usually subordinate to a larger political division. In the late 9th and early 10th centuries, Meng Zhixiang and Wang Jian were involved in operations which were in part centered in Kuizhou, which became the capital of Ningjiang Circuit (寧江).

End of Tang dynasty

Wang Jian (847–918) began his career serving in the Tang army, but with the dissolution of the Tang empire, became the founding emperor of the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms state of Former Shu (907–925), which was one of the Ten Kingdoms. Wang conquered in 903, four years before the demise of Tang, in 907.

Former Shu

Kuizhou was part of Former Shu, founded by Wang Jian as part of the aftermath of the dissolution of the Tang dynasty: Wang was in control of Kuizhou in 907, when the Tang dynasty formally is considered to have ended. Kuizhou was part of Later Tang (one of the Five Dynasties which succeeded each other in control to the north of China), after its conquest of Former Shu, in a southern extension of power.

Attack by Zhao Kuangning

Kui Prefecture, however, would not prove easy to hold. In 904, the warlord Zhao Kuangning sent an armed group up the Yangtze River to attack Kui Prefecture, still, held by Wang Jian under the title of Military Governor of Xichuan Circuit (西川, headquartered in modern Chengdu, Sichuan). Zhao's attack was repelled by Wang's adoptive son Wang Zongruan (王宗阮). Wang's general Zhang Wu (張武) subsequently built a large iron chain across the Yangtze, in order to be able to restrict travel.

Attack by Gao Jixing

In 914, Gao Jixing launched a fleet and headed west up the Yangtze, attempting to capture four prefectures which had become Former Shu territory — Kuizhou, Wanzhou (萬州), Zhongzhou (忠州), and Fu zhou(涪州), all in modern Chongqing). However, when he attacked Kui first, he was defeated by the Former Shu prefect of Kui, Wang Chengxian (王成先), and withdrew with heavy losses.

Jingnan, Later Tang, and Later Shu

Gao Conghui, whose career apexed as ruler of the Ten Kingdoms state of Jingnan, conquered Kuizhou, in about 926.

Meng Zhixiang (874–934) was a Later Tang general who was later considered to be the founder the state of Later Shu (935–965). His son Meng Renyi would be created Prince of Kui, in 950, shortly before the establishment of the Song dynasty in 960, which would eventually result in the reunification of China as one state.

Song dynasty

The Song dynasty (960 to 1279) retained Kui as a distinct political entity, and available quantitative and other data serve to illustrate the changes in population of Kuizhou and its relative status in terms of education and recruitment of officials into the national government, at several points of time during this period: data include census figures for population, records from the imperial civil service examinations, and other writings. The population figures for the time bear some interpretation because they are recorded by number of households, and the average number of persons per household and number of persons without a household is not certainly known, and was also subject to change. Other factors are also operative in terms of interpreting the data, similar to the case of other census figures. Also, some imprecision due to rounding of figures may be noted.

Population

Around the year 1100, the population of Kuizhou is enumerated at 250,000 households; in 1162, 387,000 households are recorded; in 1223, 208,000 households are reported (according to Kracke, 255 and 257).

Education and regional representation in government

A major function of the Song educational system and its accompanying formal award of graduate degrees to successful candidates was to recruit personnel to fill important and powerful governmental positions in the imperial bureaucracy. Thus, the available figures for Kuizhou versus other regions of the Song empire illustrate to some degree the relative regional quality of education and regional representation in Song governance for Kuizhou. Figures are available for certain years for the number of graduates awarded the jinshi degree (somewhat equivalent to a modern Doctor of Literature). In some cases, the number of candidates is also known for certain years. E. A. Kracke, Jr., analyzing the data concludes that regions of the Yangzi delta and the Sichuan basin are far more proportionally represented than are regions such as Kuizhou (Kracke, 255). Sima Guang and Ouyang Xiu show supporting conclusions (Kracke, 254).

Yuan dynasty

Eventually, the Song dynasty was completely defeated by the Mongol Empire, which then itself came to be divided into several regional parts, one of which organized as the Yuan dynasty of China. During the course of the destruction of the Song and subsequent reorganization vast changes in the political structure included the end of the role of Kuizhou as a distinct and important formal part of the organized Chinese political structure. However Guizhou was formally made a province only in 1413, and Marco Polo, in 1298, does mention Kuizhou as an existing province.[1]

Poetry and Culture

Kuizhou, also known as Kui Prefecture, was an important location in regard to the Classical Chinese poetry genre known as Xiaoxiang poetry, a name which is associated with the Xiaoxiang region (a semi-geographic, semi-symbolic locality). During the Tang and Song dynasties, the Xiaoxiang was associated with a long poetic tradition, going back to Qu Yuan's Li Sao, and subsequent development through the Han Dynasty into the Chuci anthology: by the time of Tang and Sung, the connotations of this Xiaoxiang (or sao) style verse included the implications of exile from court, displacement into the wilderness, and the disappointment of talented and loyal officials who were condemned to exile by the slander of inferiors. Various poets (including some of the most famous and renowned) wrote poems in Kui, in particular Du Fu and Li Bai.

Li Bai

Li Bai (also known by various name variants) was a famous Tang poet who was famous for his Kuizhou poetry. After being pardoned and recalled from exile for his role in the Anshi affair, in 756, returning down the Yangzi River, Li stopped at Baidicheng, in Kuizhou, which was the occasion of his writing his famous poem "Departing from Baidi in the Morning".

Du Fu

The famous Tang poet Du Fu (712-770) wrote hundreds of poems in Kuizhou, where he resided towards the end of his life (766-early 768). One famous poem which Du Fu wrote in Kuizhou was the influential poem "Autumn Day in Kui Prefecture". Du Fu was one of the refugees from the north who escaped from the turmoil of the Anshi disturbances, and ended up in Kui Prefecture for a time (Murck, 23-24; and, Hinton, 191). At the time, educated Han Chinese persons were a distinct minority in the area of Kuizhou, and what local Chinese language was spoken there among the majority languages had strong dialectical features, including distinct vocabulary differences, as Du Fu points out through his poetry.

See also

- "Autumn Day in Kui Prefecture"

- Baidicheng, about the town, or city

- Chongqing, the modern Kuizhou

- Eight Views of Xiaoxiang, a series of images relevant to Kuizhou

- History of the administrative divisions of China before 1912, overview including Kuizhou

- Qutang Gorge, geographic topicality

- Simians (Chinese poetry), discussing monkeys, gibbons, and other primate species associated with Kuizhou

References

Citations

- Chapter 130, « Cuigiu ».

Works

- Hinton, David (2008). Classical Chinese Poetry: An Anthology. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux. ISBN 0374105367 / ISBN 9780374105365.

- Haeger, John Winthrop, ed., (1975).Crisis and Prosperity in Sung China. Rainbow-Bridge Book Co./University of Arizona Press.

- Kracke, E. A., Jr. (1967 [1957]). "Region, Family, and Individual in the Chinese Examination System", in Chinese Thoughts & Institutions, John K. Fairbank, editor. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press.

- Murck, Alfreda (2000). Poetry and Painting in Song China: The Subtle Art of Dissent. Cambridge (Massachusetts) and London: Harvard University Asia Center for the Harvard-Yenching Institute. ISBN 0-674-00782-4.

- Paludan, Ann (1998). Chronicle of the Chinese Emperors: The Reign-by-Reign Record of the Rulers of Imperial China. New York, New York: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 0-500-05090-2

External links

- Text of Du Fu's "Autumn Day in Kui Prefecture on Ctext.org

- Text of Du Fu's "Autumn Day in Kui Prefecture" at zh.wikisource