Ouyang Xiu

Ouyang Xiu (1 August 1007 – 22 September 1072), courtesy name Yongshu, also known by his art names Zuiweng ("Old Drunkard") and Liu Yi Jushi ("Retiree Six-One"), was a Chinese essayist, historian, poet, calligrapher, politician, and epigrapher of the Song dynasty. A much celebrated writer, both among his contemporaries and in subsequent centuries, Ouyang Xiu is considered the central figure of the Eight Masters of the Tang and Song. It was he who revived the Classical Prose Movement (first begun by the two Tang dynasty masters two centuries before him) and promoted it in imperial examinations, paving the way for future masters like Su Shi and Su Zhe.

Ouyang Xiu | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

歐陽脩 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

A contemporary drawing of Ouyang Xiu | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | August 1, 1007 Mian Prefecture, Song | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | September 22, 1072 (aged 65) Ying Prefecture, Song | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Spouse(s) |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Children |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Parents |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 歐陽脩 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 欧阳修 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ouyang Yongshu (courtesy name) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 歐陽永叔 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 欧阳永叔 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Zuiweng (art name) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 醉翁 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | "Drunken Old Man" | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Liu Yi Jushi (art name) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 六一居士 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Wenzhong (posthumous name) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 文忠[note 1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Cultured and Loyal | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Ouyang Xiu's interests as a writer were remarkably diverse. As a historian, he was put in charge by Emperor Renzong of Song of creating the New Book of Tang, which was completed in 1060. He also wrote in his spare time the Historical Records of the Five Dynasties, the only book in the Twenty-Four Histories to have been written in private by a single author. As a poet, he was a noted writer of both the ci and shi genres. But it was his prose writings like Zuiweng Tingji that won him the greatest acclaim. Treatises from Ouyang's voluminous oeuvre range from studies of flowers to literary criticism and political commentaries.

Politically, Ouyang Xiu was one of the major proponents of the Qingli Reforms of the 1040s. When lead reformer Fan Zhongyan fell from power in 1045, Ouyang was also demoted to posts away from the capital. He returned to the central government only in 1054, and gradually moved up the bureaucratic ladder again, until in 1060 he was made the assistant councilor of the state. He retired from politics in 1071, after vehemently (and unsuccessfully) opposing the New Policies of Wang Anshi, whose career he very much helped.

Early life

He was born in Sichuan,[1] where his father was a judge,[2] though his family came from present-day Jishui (then known as Luling), Jiangxi. His family was relatively poor, not coming from one of the old great lineages of Chinese society. Losing his father when he was three, his literate mother was responsible for much of his early education; her method is the origin of the chengyu 修母畫荻 (xiū mǔ huàdí). He was unable to afford traditional tutoring and was largely self-taught. The writings of Han Yu were particularly influential in his development. He passed the jinshi degree exam in 1030 on his third attempt at the age of 22.[3]

Official career

After passing the jinshi exam, he was appointed to a judgeship in Luoyang,[2] the old Tang Dynasty eastern capital. While there, he found others with his interest in the writings of Han Yu.[4] Politically, he was an early patron of the political reformer Wang Anshi, but later became one of his strongest opponents. At court, he was both much loved and deeply resented at the same time.

In 1034 he was appointed to be a collator of texts[2] at the Imperial Academy in Kaifeng where he was associated with Fan Zhongyan, who was the prefect of Kaifeng. Fan was demoted, however, after criticizing the Chief Councillor and submitting reform proposals. Ouyang was later demoted as well for his defense of Fan, an action that brought him to the attention of other reform-minded people.[5]

Military threats from the Liao Dynasty and Xi Xia in the north in 1040 caused Fan Zhongyan to come back into favor. Fan offered Ouyang a post as secretary, but Ouyang refused. Instead, in 1041 Ouyang obtained a position preparing a catalogue of the Imperial Library.[5]

1043 was the high point in the first half of the eleventh century for reformers. Ouyang and Fan spurred the Qingli Reforms, a ten-point reform platform.[6] Among other things, these included improved entrance examinations for government service, elimination of favouritism in government appointments, and increased salaries.[7] They were able to implement some of these ideas in what was later called the Minor Reform of 1043, but the emperor rescinded their changes and Fan and his group fell from power. Ouyang was demoted to service in the provinces. He returned briefly to court in 1049 but was forced to serve a two-year sabbatical during the mourning period for his mother, who died in 1052.[6]

Upon his return to government service, he was appointed to the Hanlin Academy, charged with heading the commission compiling the New Book of Tang (1060). He also served as Song ambassador to the Liao on annual visits and served as examiner of the jinshi examinations, working on improving them in the process.[8]

In the early 1060s, he was one of the most powerful men in court, concurrently holding the positions of Assistant Chief Councillor, Hanlin Academician, Vice Commissioner of Military Affairs, and Vice Minister of Revenues.[8]

Around the time of the ascension of Emperor Shenzong of Song in 1067, Ouyang was charged with several crimes, including having sexual relations with his daughter-in-law. While the charges had no credibility, the investigation alone damaged Ouyang's reputation. His request to retire was declined by the emperor,[9] who sent him to magistrate positions in Shandong and Anhui. While a magistrate in Shandong, he opposed and refused to carry out reforms advocated by Wang Anshi, particularly a system of low-interest loans to farmers.[2] He was finally permitted to retire in 1071.[9]

Prose

In his prose works, he followed the example of Han Yu, promoting the Classical Prose Movement. While posted in Luoyang, Ouyang founded a group who made his “ancient prose” style a public cause. He is listed as one of the Eight Masters of the Tang and Song.

Among his most famous prose works is the Zuiweng Tingji (lit. 'An Account of the Old Toper's Pavilion'). The Zuiweng Pavilion near Chuzhou is named in his honor[10] whilst the poem is a description of his pastoral lifestyle among the mountains, rivers and people of Chuzhou. The work is lyrical in its quality and acclaimed as one of the highest achievements of Chinese travel writing. Chinese commentators in the centuries immediately following the work's composition focused on the nature of the writing. Huang Zhen said that the essay is an example of "using writing to play around". It was agreed that the essay was about fengyue, the enjoyment of nature. During the Qing Dynasty, however, commentators began to see past the playfulness of the piece to the thorough and sincere joy that the author found in the joy of others.[11]

Historian

Ouyang led the commission compiling the New Book of Tang, which completed its work in 1060. He wrote New History of the Five Dynasties on his own following his official service. The book was not discovered until after his death.[12]

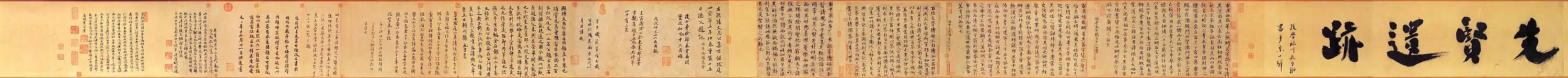

As a historian, he has been criticised as overly didactic, but he played an important role in establishing the use of epigraphy as a historiographic technique. Epigraphy, as well as the practice of calligraphy, figured in Ouyang's contributions to Confucian aesthetics. In his Record of the Eastern Study he states how literary minded gentlemen might utilize their leisure to nourish their mental state. The practice of calligraphy and the appreciation of associated art objects were integral to this Daoist-like transformation of intellectual life.[13]

The Ming dynasty writer Feng Menglong recorded a possibly apocryphal anecdote regarding Ouyang's writing style in his collection of short stories Gujin Tan'gai 《古今譚概》.[14] As the story goes, during one of Ouyang's trips outside the Hanlin Academy with his associates, they witnessed an unusual event: a horse became spooked, galloped down a busy street, and kicked to death a dog sleeping there. Ouyang challenged his two associates to express this event in writing. One wrote: "A dog was lying in the thoroughfare and was kicked to death by a galloping horse," while the other wrote: "A horse galloped down a thoroughfare. A lying dog encountered it and was killed." Ouyang teased his junior colleagues, "A history book in your hands would remain incomplete after ten thousand volumes." When asked for his own rendering, Ouyang, replying with a smile, wrote: "A galloping horse killed a dog in its path."

Poetry

His poems are generally relaxed, humorous and often self-deprecatory; he gave himself the title The Old Drunkard. He wrote both shi and ci. His shi are stripped down to the essentials emphasised in the early Tang period, eschewing the ornate style of the late Tang. He is best known, however, for his ci.[15] In particular, his series of ten poems entitled West Lake is Good set to the tune Picking Mulberries helped to popularise the genre as a vehicle for serious poetry.

Ouyang's poetry, especially the mature works of the 1050s, dealt with new themes that previous poets had avoided. These include interactions with friends, family life, food and beverages, antiques, and political themes. He also used an innovative style containing elements that he had learned from his prose writing. This includes his use of self-caricature and exaggeration.[16] Ouyang's poetry bears the characteristic of literary playfulness common to Northern Song poetry. For example, many poems have titles that indicate that they originated in rhyme games, and feature extensive rhyming schemes throughout.[17] Below is one of the many poems Ouyang Xiu wrote about the famed West Lake in Hangzhou.

Deep in Spring, the Rain's Passed (Picking Mulberries) [18]

Original Chinese text採桑子

春深雨過西湖好,

百卉爭妍,

蝶亂蜂喧,

晴日催花暖欲然。

蘭橈晝舸悠悠去,

疑是神仙。

返照波間,

水闊風高颺管絃。

Legacy

He died in 1072 in present-day Fuyang, Anhui. His influence was so great, even opponents like Wang Anshi wrote moving tributes on his behalf. Wang referred to him as the greatest literary figure of his age.

During the Ming Dynasty, Li Dongyang, who rose to be the highest official in the Hanlin Academy, was an admirer of Ouyang Xiu, regarding him as "an ideal example of the scholar-official committed to both public service and literary art", and praising his writings for their tranquility and propriety.[19]

Notes

- Ouyang Xiu was also known as "Ouyang, Lord Wenzhong" (歐陽文忠公) because of his posthumous name.

References

Citations

- Mote, F.W. (1999). Imperial China: 900–1800. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. p. 120. ISBN 0-674-01212-7.

- "Ouyang Xiu -- Britannica Online Encyclopedia". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 2007. Retrieved 2007-09-30.

- Mote, F.W. (1999). Imperial China: 900–1800. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. pp. 120–121. ISBN 0-674-01212-7.

- Mote p. 121

- Mote p. 123

- Mote p. 124

- Mote p. 137

- Mote p. 125

- Mote p. 126

- "Old Toper's Chant". Retrieved March 8, 2011.

- Lian, Xianda (2001). "The Old Drunkard Who Finds Joy in His Own Joy -Elitist Ideas in Ouyang Xiu's Informal Writings". Chinese Literature: Essays, Articles, Reviews. Chinese Literature_ Essays, Articles, Reviews. 23: 1–29. doi:10.2307/495498. JSTOR 495498.

- "History of the Five Dynasties". World Digital Library. 1280–1368. Retrieved 2013-09-05.

- Carpenter, Bruce E., "Confucian Aesthetics and Eleventh Century Ou-yang Hsiu" in Tezukayama University Review (Tezukayama Daigaku Ronshu) Nara, Japan, 1988, no. 59, pp. 111–118. ISSN 0385-7743

- 馮夢龍《古今譚概·書馬犬事》 歐陽公在翰林時,常與同院出遊。有奔馬斃犬,公曰:「試書其一事。」一曰:「有犬臥於通衢,逸馬蹄而殺之。」一曰:「有馬逸於街衢,臥犬遭之而斃。」公曰:「使子修史,萬卷未已也。」曰:「內翰云何?」公曰:「逸馬殺犬於道。」相與一笑。

- "Ouyang Xiu". The Anchor Book of Chinese Poetry Web Companion. Whittier College. 2004. Archived from the original on 20 February 2007. Retrieved 2007-09-30.

- Hawes, Colin (1999). "Mundane Transcendence: Dealing with the Everyday in Ouyang Xiu's Poetry". Chinese Literature: Essays, Articles, Reviews (CLEAR). Chinese Literature_ Essays, Articles, Reviews (CLEAR). 21: 99–129. doi:10.2307/495248. JSTOR 495248.

- Hawes, Colin (2000). "Meaning beyond Words: Games and Poems in the Northern Song". Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies. Harvard-Yenching Institute. 60 (2): 355–383. doi:10.2307/2652629. JSTOR 2652629.

- "Ouyang Xiu English Translations". 2007. Retrieved 2007-09-30.

- Chang, Kang-i Sun; Owen, Stephen (2010). The Cambridge History of Chinese Literature, Volume 2. Cambridge University Press. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-521-85559-4.

Sources

- Books

- Egan, Ronald C. (1984). The Literary Works of Ou-yang Hsiu. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-25888-X.

- Mote, F.W. (1999). Imperial China: 900-1800. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. pp. 119–126, 135–138. ISBN 0-674-01212-7.

- Articles

- Biography by James T.C. Liu in Franke, Herbert, Sung Biographies, Wiesbaden, 1976,vol. 2, pp. 808–816. ISBN 3-515-02412-3.

- Carpenter, Bruce E., "Confucian Aesthetics and Eleventh Century Ou-yang Hsiu" in Tezukayama University Review (Tezukayama Daigaku Ronshu) Nara, Japan, 1988, no. 59, pp. 111–118. ISSN 0385-7743.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ouyang Xiu. |

- Ouyang Xiu and his Calligraphy Gallery at China Online Museum

- Britannica.com

- Biographical profile

- English translations of the ten "West Lake is Good" poems

- Works by or about Ouyang Xiu at Internet Archive

- Works by Ouyang Xiu at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)