Lake Wānaka

Lake Wānaka (also spelled Lake Wanaka) is New Zealand's fourth-largest lake.[2][3] In the Otago region, it is 278 meters above sea level,[4] covers 192 km2 (74 sq mi),[5] and is more than 300 m (980 ft) deep.

| Lake Wānaka | |

|---|---|

View of Lake Wānaka from Mt. Roy. | |

Lake Wānaka | |

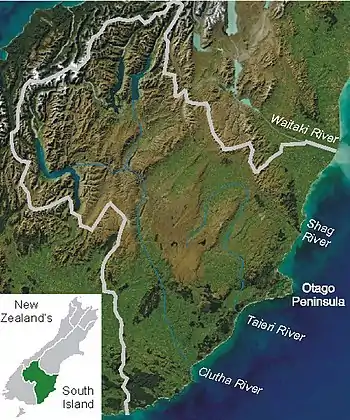

Location on the South Island | |

| Location | Queenstown-Lakes District, Otago, South Island |

| Coordinates | 44°30′S 169°08′E |

| Primary outflows | Clutha River / Mata-Au |

| Basin countries | New Zealand |

| Max. length | 42 km (26 mi) |

| Max. width | 10 km (6.2 mi) |

| Surface area | 192 km2 (74 sq mi) |

| Max. depth | est. 311 m (1,020 ft)[1] |

| Surface elevation | 278 m (912 ft) |

| Islands | Harwich Island, Mou Tapu, Mou Waho, Ruby Island, Stevensons Island |

"Wānaka" is the South Island dialect pronunciation of wānanga, which means "the lore of the tohunga or priest"[2] or a place of learning.[6] [Note 1]

The town near the foot of the lake is named Wanaka. A Kāti Māmoe settlement at the site of the modern township was Para karehu.[9]

Geography

Geography

Lake Wānaka lies at the heart of the Otago Lakes in the lower South Island of New Zealand. The township of Wanaka, which sits in a glacier-carved basin on the shores of the lake, is the gateway to Mt Aspiring National Park. Lake Hāwea is a 15-minute drive away, en route to the frontier town of Makarora, the last stop before the West Coast Glacier region. To the south is the historic Cardrona Valley, a popular scenic alpine route to neighbouring Queenstown.

Geology

Lake Wānaka lies in a u-shaped valley formed by glacial erosion during the last ice age more than 10,000 years ago. It is fed by the Matukituki and Makarora Rivers, and is the source of the Clutha River / Mata-Au.

At its greatest extent, which is roughly along a north–south axis, the lake is 42 kilometres long. Its widest point, at the southern end, is 10 kilometres. The lake's western shore is lined with high peaks rising to over 2000 metres above sea level. Along the eastern shore the land is also mountainous, but the peaks are somewhat lower.

Nearby Lake Hāwea lies in a parallel valley carved by a neighbouring glacier eight kilometres to the east. At their closest point (a rocky ridge called The Neck), the lakes are only 1000 metres apart.[10]

Small islands towards the foot of the lake include Ruby Island, Stevensons Island and Harwich Island. Some host ecological sanctuaries, such as one for buff weka on Stevensons Island.[11]

The towns of Wanaka and Albert Town are near the lake's outflow into the Clutha / Mata-Au.

Climate

| Climate data for Lake Wānaka | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 23.9 (75.0) |

23.4 (74.1) |

20.8 (69.4) |

17.3 (63.1) |

12.2 (54.0) |

8.4 (47.1) |

8.4 (47.1) |

11.0 (51.8) |

14.4 (57.9) |

16.8 (62.2) |

19.8 (67.6) |

21.9 (71.4) |

16.5 (61.7) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 10.8 (51.4) |

10.4 (50.7) |

8.4 (47.1) |

5.1 (41.2) |

1.6 (34.9) |

−0.9 (30.4) |

−1.2 (29.8) |

−0.2 (31.6) |

2.4 (36.3) |

5.0 (41.0) |

7.3 (45.1) |

9.6 (49.3) |

4.9 (40.7) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 56.9 (2.24) |

50.2 (1.98) |

60.7 (2.39) |

56.4 (2.22) |

62.7 (2.47) |

54.5 (2.15) |

52.2 (2.06) |

52.8 (2.08) |

56.4 (2.22) |

63.1 (2.48) |

54.7 (2.15) |

51.9 (2.04) |

672.5 (26.48) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 231.5 | 201.7 | 182.6 | 164.0 | 135.5 | 120.5 | 126.6 | 155.8 | 172.5 | 193.8 | 202.2 | 212.1 | 2,098.8 |

| Source: http://www.lakewanaka.co.nz/content/library/Weather_data.pdf | |||||||||||||

Human history

Exploration and settlement

For Māori, the Wānaka area was a natural crossroads. The Haast Pass gave access to the West Coast and its pounamu; the Cardrona Valley led to the natural rock bridge "Whatatorere", which was the only place that the Kawarau River and Clutha River / Mata-Au could be crossed without boats.[12] Native reeds were used to build mōkihi, small boats that enabled a swift return downriver to the east coast.[13][14] The Cromwell basin supported a large population of moa, which were hunted to extinction about 500 years ago.[12]

Until the early nineteenth century, Wānaka was visited annually by Ngāi Tahu who sought pounamu in the mountains above the Haast River and hunted eels and birds over summer, returning to the east coast by descending the Clutha River / Mata-Au in mōkihi reed boats.[13]

According to the Ngāi Tahu, Lake Wānaka was dug by the Waitaha explorer Rākaihautū with his kō named Tūwhakaroria. After Waitaha arrived in the Uruao waka at Whakatū (Nelson), Rākaihautū divided his people into two groups. Rākaihautū led his group down the middle of the island, digging the freshwater lakes of Te Waipounamu.[8]

Numerous kāinga mahinga kai (food-gathering places) and kāinga nohoanga (settlements) were located around the lake. The Kāti Māmoe settlement at the site of modern Wanaka was named Para karehu. The area was invaded by the Ngāi Tahu in the early 18th century.[9]

Ngāi Tahu use of the land was ended by attacks by North Island tribes.[12] In the last years of the Musket Wars, in 1836 the Ngati Tama chief Te Puoho led a 100-person war party, armed with muskets, down the West Coast and over the Haast Pass: they fell on the Ngāi Tahu encampment between Lake Wānaka and Lake Hāwea, capturing 10 people and killing and eating two children.[15] Although Te Puoho was later killed by the southern Ngāi Tahu leader Tuhawaiki,[16] Māori seasonal visits to the area ceased.

The first known map of Lake Wānaka was drawn in 1844 by the southern Ngāi Tahu leader Te Huruhuru.[8] The first European to see the lake was Nathaniel Chalmers in 1853.[17] Guided by Reko and Kaikoura, he walked from Tuturau (Southland) to the lake via the Kawarau River. However he was stricken by dysentery, so his guides returned him down the Clutha, shooting the rapids in a mōkihi reed boat.[18]

By 1861, several sheep stations had been established in and around the south end of the lake, and in 1862, the lake itself was surveyed in a whaleboat.[7] The early European name was Lake Pembroke.[19]

Current use and tourism

In addition to ongoing sheep farming, the lake is now a popular resort, and is much used in the summer for fishing, boating and swimming. The nearby mountains and fast-flowing rivers allow for adventure tourism year-round, with jetboating and skiing facilities located nearby.[20]

With Queenstown airport close by, tourism mirrors that of the surrounding areas.

Conservation

As one of the few lakes in the South Island with an unmodified shoreline, the lake is protected by special legislation, the Lake Wanaka Preservation Act of 1973. The Act established a 'Guardians of Lake Wanaka' group, appointed by the Minister of Conservation, which advises on measures to protect the lake.[21]

Oxygen weed (Lagarosiphon major), an aquarium plant and invasive species native to Southern Africa, has been a problem in the lake's ecosystem for some time. Attempts to eradicate the weed have not been successful. Substantial suction dredging operations have shown promise, but tend to miss isolated spots which then regrow into larger weed beds.[22]

In popular culture

That Wanaka Tree – a willow growing just inside the lake – is a tourist attraction in its own right, featuring on many tourists' Instagram feeds.[23] The tree had its lower branches cut by vandals in 2020.[24]

In film

The region has been the setting for many international films, including The Lord of the Rings,[25] The Hobbit,[26] the Legend of S,[27] and A Wrinkle in Time.[28] Lake Wānaka was mentioned several times in the 2006 movie Mission: Impossible III as a location the lead couple visited and as the answer to Ethan Hunt's question on the phone to verify the identity of his wife.

The New Zealand cook and author Annabel Langbein, who owns a small estate at the side of the lake, filmed her series The Free Range Cook and Simple Pleasures here.

As a reported refuge

New Zealand has been reported to be a favoured refuge for the 'super rich' in the event of a cataclysm.[29] One such high net worth individual is Peter Thiel, who purchased 193 hectares (480 acres) of lakeside land in 2015,[30] although he had not developed it as of 2020.[31]

See also

- Lakes of New Zealand

- List of lakes in New Zealand

- Otago Geography

- Sentinel Peak (New Zealand)

- Roys Peak

Notes

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lake Wanaka. |

- McKinnon, Malcolm (29 July 2015). "Lakes Wānaka and Hāwea". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand.

- "Place name detail: Lake Wānaka". New Zealand Gazetteer. New Zealand Geographic Board. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- Lake Wānaka (from the Tourism New Zealand website)

- Otago Regional Council (Lake level monitoring)

- Taonga, New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage Te Manatu. "19. – Otago places – Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand". www.teara.govt.nz.

- "Wanaka". New Zealand History. Nga korero a ipurangi o Aotearoa. New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Retrieved 7 November 2020.

- Wanaka, Lake (from Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand, The 1966 New Zealand Encyclopaedia)

- "Lake Wānaka". Kā Huru Manu. Nga Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- Taylor, W. A. "Lore and History of the South Island Maori". New Zealand Electronic Texts Collection. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- Lakes: Laka Wanaka and Hawea Archived 21 April 2012 at WebCite (from the Tourism New Zealand website)

- "What's Up DOC – Wanaka". Television New Zealand. Retrieved 13 October 2011.

- Janet Stephenson, Heather Bauchop, and Peter Petchey (2004). Bannockburn Heritage Landscape Study (PDF). p. 29.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Malcolm McKinnon. "Otago region - Māori history and whaling". Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 7 January 2021.

- Hoturoa Barclay-Kerr. "Waka – canoes - Other types of waka". Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 7 January 2021.

- S Percy Smith (1910). History and Traditions of the Maoris of the West Coast North Island of New Zealand Prior to 1840. New Plymouth: Polynesian Society.

- Atholl Anderson (1990). "Te Puoho-o-te-rangi". Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. 1. Retrieved 11 July 2017.

- Jock Phillips. "European exploration – Otago and Southland". Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 11 July 2017.

- Roger Frazer (1990). "Chalmers, Nathanael". Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Dictionary of New Zealand Biography. 1. Retrieved 13 July 2017.

- Zealand, National Library of New. "Papers Past – PASSIM NOTES. (Otago Witness, 1889-04-25)". paperspast.natlib.govt.nz.

- "Wanaka Tourism".

- Briefing to the incoming Minister of Conservation 2011 – containing information about Statutory bodies, including the Guardians (from the Department of Conservation website, Friday 14 December 2012)

- "Assessment of the 2005/06 Lagarosiphon major programme in Lake Wanaka" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 September 2009. (1.20 MiB) (NIWA report, June 2006, from the Land Information New Zealand website)

- "Wanaka's famous Instagram tree attacked with a saw". The Guardian. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- Marcus, Lilit (20 March 2020). "New Zealand's most famous tree, 'That Wanaka Tree,' vandalized". CNN Travel. CNN. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- "The Lord of the Rings Location: Tarras & Wanaka".

- "The Hobbit Trilogy Filming Locations".

- Otago Daily Times (5 May 2017). "Chinese fantasy filming in Wanaka". Retrieved 27 January 2018.

- "Witherspoon, Winfrey and Kaling in Wanaka and Lake Hāwea".

- Osnos, Evan (23 January 2017). "Doomsday Prep for the Super-Rich". The New Yorker (30 January 2017). Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- "Facebook billionaire Peter Thiel a Kiwi citizen, owns Wanaka estate". New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- "Thiel's Wanaka estate reportedly left 'neglected'". Otago Daily Times. 16 May 2020. Retrieved 17 May 2020.