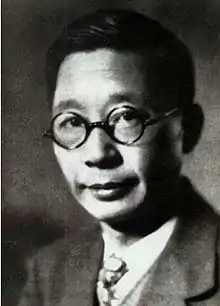

Lao She

Shu Qingchun (3 February 1899 – 24 August 1966), courtesy name Sheyu, best known by his pen name Lao She, was a Chinese novelist and dramatist. He was one of the most significant figures of 20th-century Chinese literature, and is best known for his novel Rickshaw Boy and the play Teahouse (茶館). He was of Manchu ethnicity, and his works are known especially for their vivid use of the Beijing dialect.

Lao She | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||

| Born | Shu Qingchun 3 February 1899 Beijing, Qing Empire | ||||||||||

| Died | 24 August 1966 (aged 67) Beijing | ||||||||||

| Resting place | Babaoshan Revolutionary Cemetery, Beijing | ||||||||||

| Pen name | Lao She | ||||||||||

| Occupation | Novelist, dramatist | ||||||||||

| Language | Chinese | ||||||||||

| Alma mater | Beijing Normal University | ||||||||||

| Notable works | Rickshaw Boy Teahouse | ||||||||||

| Spouse | Hu Jieqing | ||||||||||

| Children | 4 | ||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||

| Chinese | 老舍 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Shu Qingchun | |||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 舒慶春 | ||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 舒庆春 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Shu Sheyu | |||||||||||

| Chinese | 舒舍予 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

Biography

Early life

Lao She was born Shu Qingchun (舒慶春) on 3 February 1899 in Beijing, to a poor Manchu family of the Sumuru clan belonging to the Plain Red Banner. His father, who was a guard soldier, died in a street battle with the Eight-Nation Alliance Forces in the course of the Boxer Rebellion events in 1901. "During my childhood," Lao She later recalled, "I didn't need to hear stories about evil ogres eating children and so forth; the foreign devils my mother told me about were more barbaric and cruel than any fairy tale ogre with a huge mouth and great fangs. And fairy tales are only fairy tales, whereas my mother's stories were 100 percent factual, and they directly affected our whole family."[1] In 1913, he was admitted to the Beijing Normal Third High School (now Beijing Third High School), but had to leave after several months because of financial difficulties. In the same year, he was accepted to Beijing Normal University, from which he graduated in 1918.[2]

Teaching and writing career

Between 1918 and 1924, Lao She was involved as administrator and faculty member at a number of primary and secondary schools in Beijing and Tianjin. He was highly influenced by the May Fourth Movement (1919). He stated, "[The] May Fourth [Movement] gave me a new spirit and a new literary language. I am grateful to [The] May Fourth [Movement], as it allowed me to become a writer."

He went on to serve as lecturer in the Chinese section of the School of Oriental Studies (now the School of Oriental and African Studies) at the University of London from 1924 to 1929. During his time in London, he absorbed a great deal of English literature (especially Dickens, whom he adored) and began his own writing. His later novel 二马 (Mr Ma and Son) drew on these experiences.[3] Also at that time, Lao She's pen name changed from She Yu to Lao She in his second novel "Old Zhang's Philosophy" or "The Philosophy of Lao Zhang"(Lao Zhang De Zhe Xue),[4] first published on Fiction Monthly (小说月报). During 1925-28, he lived in 31 St James's Gardens, Notting Hill, London, W11 4RE, Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea.[5]

In the summer of 1929, he left Britain for Singapore, teaching at the Chinese High School. Between his return to China in the spring of 1930 until 1937, he taught at several universities, including Cheeloo University and Shandong University (Qingdao).

Lao She was a major popularizer of humor writing in China, especially through his novels, his short stories and essays for journals like Lin Yutang's The Analects Fortnightly (Lunyu banyuekan, est. 1932), and his stage plays and other performing arts, notably xiangsheng.[6]

On 27 March 1938, The All-China Resistance Association of Writers and Artists (中华全国文艺界抗敌协会) was established with Lao She as its leader. The purpose of this organization was to unite cultural workers against the Japanese, and Lao She was a respected novelist who had remained neutral during the ideological discussions between various literary groups in the preceding years.

In March 1946, Lao She travelled to the United States on a two-year cultural grant sponsored by the State Department, lecturing and overseeing the translation of several of his novels, including The Yellow Storm (1951) and his last novel, The Drum Singers (1952; its Chinese version, Gu Shu Yi Ren, was not published until 1980). He stayed in the US from 1946 until December 1949. During Lao She's traveling, his friend, Pearl S. Buck, and her husband, had served as sponsors and they helped Lao She live in the U.S. After the People's Republic of China was established, Lao She rejected Buck's advice to stay in America and came back to China. Rickshaw Boy was translated by Buck in the early 1940s. This action helped Rickshaw Boy became a best seller book in America.[7]

In March 1946, Lao She travelled to the United States on a two-year cultural grant sponsored by the State Department, lecturing and overseeing the translation of several of his novels, including The Yellow Storm (1951) and his last novel, The Drum Singers (1952; its Chinese version, Gu Shu Yi Ren, was not published until 1980).

Marriage and Family

Lao She was married to painter Hu Jieqing; together they had a son and three daughters.

Death

Like numerous other intellectuals in China, Lao She experienced mistreatment when the Cultural Revolution began in 1966. Condemned as a counterrevolutionary, he was paraded by the Red Guards through the streets and beaten publicly at the door steps of the Temple of Confucius in Beijing. According to the official record, this abuse left Lao She greatly humiliated both mentally and physically, and he committed suicide by drowning himself in Beijing's Taiping Lake on 24 August 1966. Leo Ou-fan Lee mentioned the possibility that Lao She was murdered.[8] However, no reliable information has emerged to verify definitively the actual circumstances of Lao's death.[9] His relatives were accused of implication in his "crimes", but rescued his manuscripts after his death, hiding them in coal piles and a chimney and moving them from house to house.

Works

Lao She's first novel, The Philosophy of Lao Zhang (老张的哲学 Lao Zhang de Zhexue) was written in London (1926) and modeled on Dickens' Nicholas Nickleby, but is set among students in Beijing.[10] His second novel, Zhao Ziyue (赵子曰, 1927) is set in the same Beijing milieu, but tells the story of a 26-year-old college student's quest for the trappings of fame in a corrupt bureaucracy.[11] Both "The Philosophy of Lao Zhang" and "Zhao Ziyue" were Lao She's novels which expressed the native Peking lives and memories. Among Lao She's most famous stories is Crescent Moon (月芽儿, Yuè Yár), written in the early stage of his creative life. It depicts the miserable life of a mother and daughter and their deterioration into prostitution.

Mr Ma and Son

Mr. Ma and Son showed another writing style for Lao She. He described Mr. Ma and his son's life in London Chinatown, showing the poor situation of Chinese people in London. These were praised as reflecting Chinese students' experiences. Lao She used funny words to show cruel social truths.[12] From "Mr. Ma and Son", Lao She pointed the stereotype included appearances and spirits and he hoped to get rid of these dirty impressions.[13]

Cat Country

Cat Country is a satirical fable, sometimes seen as the first important Chinese science fiction novel, published in 1932 as a thinly veiled observation on China. Lao She wrote it from the perspective of a visitor to the planet Mars. The visitor encountered an ancient civilisation populated by cat-people. The civilisation had long passed its glorious peak and had undergone prolonged stagnation. The visitor observed the various responses of its citizens to the innovations by other cultures. Lao She wrote Cat Country in direct response to Japan's invasion of China (Manchuria in 1931, and Shanghai in 1932).

Rickshaw Boy

His novel Rickshaw Boy (also known in the West as Camel Xiangzi or Rickshaw) was published in 1936. It describes the tragic life of a rickshaw-puller in Beijing of the 1920s and is considered to be a classic of modern Chinese literature. The English version Rickshaw Boy became a US bestseller in 1945; it was an unauthorized translation that added a bowdlerized happy ending to the story. In 1982, the original version was made into a film of the same title.

His other important works include Four Generations Under One Roof (四世同堂, 1944, abridged as The Yellow Storm), a novel describing life during the Japanese occupation. His last novel, The Drum Singers (1952), was first published in English in the United States.

Teahouse

Teahouse is a play in three acts, set in a teahouse called "Yu Tai" in Beijing from 1898 until the eve of the 1949 revolution. First published in 1957, the play is a social and cultural commentary on the problems, culture, and changes within China during the early twentieth century.

Promotion of Baihua (National Language)

Lao She advocated the use of Baihua, the use of plain language in written Chinese. Baihua evolved a new language from classic Chinese during the May Fourth Movement. As the All-China League of Resistance Writers leader, he found he needed to abandon the use of classical Chinese for a more accessible modern style. Lao She was an early user of Baihua and other writers and artists followed his lead. Modern written Chinese is largely in the plainer Baihua style.[14]

Legacy

After the end of the Cultural Revolution, Lao She was posthumously "rehabilitated" in 1978 and his works were republished. Several of his stories have been made into films, including This Life of Mine (1950, dir. by Shi Hui), Dragon Beard Ditch (1952, dir. by Xian Qun), Rickshaw Boy (1982, dir. by Ling Zifeng), The Teahouse (1982, dir. by Xie Tian), The Crescent Moon (1986, dir. by Huo Zhuang), The Drum Singers (1987, dir. by Tian Zhuangzhuang), and The Divorce (1992, dir. by Wang Hao-wei). Tian Zhuangzhuang's adaptation of The Drum Singers, also known as Street Players, was mostly shot on location in Sichuan. Some of Lao She's plays have also been staged in the recent past, including Beneath the Red Banner in 2000 in Shanghai, and Dragon's Beard Ditch in 2009 in Beijing as part of the celebration of the writer's 110th birthday.

Lao She's former home in Beijing is preserved as the Lao She Memorial Hall, opened to the public as a museum of the writer's work and life in 1999. Originally purchased in 1950, when it was 10 Fengsheng Lane, Naicifu, the address of the traditional courtyard house is now 19 Fengfu Lane. It is close to Wangfujing, in Dongcheng District. Lao She lived there until his death 16 years later. The courtyard contains persimmon trees planted by the writer. His wife called the house 'Red Persimmon Courtyard'.[15]

The Lao She Literary Award has been given every two to three years starting in the year 2000. It is sponsored by the Lao She Literature Fund and can only be bestowed on Beijing writers.[16]

The Laoshe Tea House, a popular tourist attraction in Beijing that opened in 1988 and features regular performances of traditional music, is named after Lao She, but features primarily tourist-oriented attractions, and nothing related to Lao She.[17]

Notes

- Lao Shê in Modern Chinese Writers, ed. by Helmut Martin and Jeffrey Kinkley, 1992

- Kwok-Kan Tam. "Introduction". 駱駝祥子. p. x.

- Witchard, Lao She in London

- Lyell, William A. "Lao She(3 February 1899-25 August 1966)". Dictionary of Literary Biography. Chinese Fiction Writers, 1900-1949. 328: 104–122 – via Gale Literature.

- https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/visit/blue-plaques/lao-she/

- Christopher Rea, "The Age of Irreverence: A New History of Laughter in China" (California, 2015), chapter 6: "The Invention of Humor"

- Wang, David Der-wei, ed. A New Literary History of Modern China. Cumberland: Harvard University Press, 2017. Page.580-583 Accessed December 16, 2020. ProQuest Ebook Central.

- Lee, Leo Ou-Fan (2002). Merle Goldman & Leo Ou-Fan Lee (ed.). An Intellectual History of Modern China. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 226. ISBN 0-521-79710-1.

- http://www.scmp.com/article/358800/mystery-lao-she

- Blades of Grass: The Stories of Lao She 1997 Page 307

- p.75

- Witchard, Anne. Lao She in London. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2012. Introduction, Chapter 3, Chapter 4 Accessed December 16, 2020. ProQuest Ebook Central.

- Vohra, Ranbir (1974). Lao She and the Chinese Revolution. The First Novel (1924-1929). Cambridge, Mass: East Asian Research Center, Harvard University; distributed by Harvard University Press. pp. Page. 38–41. ISBN 0674510755.

- Denton, Kirk, Fulton, Bruce, and Orbaugh, Sharalyn. The Columbia Companion to Modern East Asian Literature. New York: Columbia University Press, 2003. Page. 311-313 Accessed December 16, 2020. ProQuest Ebook Central.

- Lao She Museum

- "Literary Award Honors Realism", China Daily, 28 October 2002, archived from the original on 7 July 2011, retrieved 27 April 2010

Selected works in translation

Fiction

- Camel Xiangzi (駱駝祥子 /Luo tuo Xiangzi) Translated by Xiaoqing Shi. Bloomington; Beijing: Indiana University Press; Foreign Languages Press, 1981. ISBN 0253312965

- Rickshaw. (駱駝祥子 /Luo tuo Xiangzi) Translated by Jean James. Honolulu: University Press of Hawaii, 1979. ISBN 0824806166

- Rickshaw Boy. (駱駝祥子 /Luo tuo Xiangzi) Translated by Evan King and Illustrated by Cyrus Leroy Baldridge. New York: Reynal & Hitchcock, 1945.

- Rickshaw Boy: A Novel. Translated by Howard Goldblatt New York: Harper Perennial Modern Chinese Classics, 2010. ISBN 9780061436925.

- 駱駝祥子 [Camel Xiangzi] (in English and Chinese). Trans. Shi Xiaojing (中英對照版 [Chinese-English Bilingual] ed.). Hong Kong: Chinese University Press. 2005. ISBN 962-996-197-0. Retrieved 8 March 2011.CS1 maint: others (link)

- The Drum Singers. Translated by Helena Kuo. New York: Harcourt, Brace, 1952.

- The Quest for Love of Lao Lee. New York: Reynal & Hitchcock, 1948. Translated by Helena Kuo.

- The Yellow Storm (also known as Four Generations Under One Roof). New York: Harcourt, Brace, 1951. Translated by Ida Pruitt.

- Cat Country, a Satirical Novel of China in the 1930s.(貓城記 / Mao cheng ji) Translated by William A. Lyell. Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 1970. Republished – Melbourne: Penguin Group, 2013.

- Mr Ma and Son: Two Chinese in London. Translated by William Dolby. Edinburgh: W. Dolby, 1987. Republished – Melbourne: Penguin Group, 2013.

- Blades of Grass the Stories of Lao She. Translated by William A. Lyell, Sarah Wei-ming Chen and Howard Goldblatt. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, 1999. ISBN 058525009X

- Crescent Moon and Other Stories. (月牙兒 Yue ya er) Beijing, China: Chinese Literature, 1985. ISBN 0835113345

Plays

- Dragon Beard Ditch: A Play in Three Acts. Peking: Foreign Languages Press, 1956.

- Teahouse: A Play in Three Acts. Translated by John Howard-Gibbon. Beijing: Foreign Languages Press, 1980; rpr Hong Kong, Chinese University Press. . ISBN 0835113493

Further reading

- Chinese Writers on Writing featuring Lao She. Ed. Arthur Sze. (Trinity University Press, 2010).

- Vohra, Ranbir. Lao She and the Chinese Revolution. Harvard University Asia Center, 1974. Volume 55 of Harvard East Asian Monographs. ISBN 0674510755, 9780674510753.

- Rea, Christopher. The Age of Irreverence: A New History of Laughter in China. University of California Press, 2015. ISBN 9780520283848

- Anne Veronica Witchard, Lao She in London (Hong Kong China: Hong Kong University Press, HKU, 2012). ISBN 9789882208803.

- Ch 4, "Melancholy Laughter: Farce and Melodrama in Lao She's Fiction," in Dewei Wang. Fictional Realism in Twentieth-Century China : Mao Dun, Lao She, Shen Congwen. New York: Columbia University Press, 1992. ISBN 0231076568. Google Book:

- Sascha Auerbach, "Margaret Tart, Lao She, and the Opium-Master's Wife: Race and Class among Chinese Commercial Immigrants in London and Australia, 1866–1929," Comparative Studies in Society and History 55, no. 1 (2013):35–64.

Portrait

- Lao She. A Portrait by Kong Kai Ming at Portrait Gallery of Chinese Writers (Hong Kong Baptist University Library).

External links

- Memorial of Victims of the Cultural Revolution, Lao She (中国文革受难者纪念馆·老舍)

- Petri Liukkonen. "Lao She". Books and Writers

- Synopsis of the play "Teahouse."

- Drama "Teahouse" wows American audiences China Daily. 16 November 2005.

- Anne Witchard's article on the London Fictions website about 'Mr Ma and Son'

- Lao She Papers at the Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University, New York, NY