Laricoideae

The Laricoideae are a subfamily of the Pinaceae, a Pinophyta division family. They take their name from the genus Larix (larches), which contains inside most of the species of the group and is one of only two deciduous genera of the pines complex (together with Pseudolarix, which however belongs to a different subfamily, the Abietoideae). Ecologically important trees, the Laricoideae form pure or mixed forest associations often dominant in the ecosystems in which they are present, thanks also to their biological adaptations to natural disturbances, to reproductive strategies put in place and high average longevity of the individuals. Currently are assigned to this subfamily three genera (Larix, Pseudotsuga and Cathaya) and its members can be found only in Northern Hemisphere.[1] The various species live for the most part in temperate or cold climates and are the more northerly conifers; some constitute an important source of timber and non-timber forest products.

| Laricoideae | |

|---|---|

| |

| Subalpine larch (Larix lyallii) in Wenatchee National Forest, Washington, U.S. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Division: | Pinophyta |

| Class: | Pinopsida |

| Order: | Pinales |

| Family: | Pinaceae |

| Subfamily: | Laricoideae (Rendle) Pilg. & Melch. (1954) |

| Type genus | |

| Larix | |

| Genera | |

Description

The species of the subfamily Laricoideae are evergreen or deciduous trees that can reach the greater heights in the Pinaceae family (over 100 meters with Pseudotsuga menziesii var. menziesii[2]). The leaves are needle-like[1] and have primary stomatal bands only on the abaxial surface (below the phloem vessels). All members are monoecious, with separate sexes on the same plant but in different reproductive structures. The annual cones (strobili) have no distinct umbo and the scales show a broad base which, at observation, completely hides the seeds from the abaxial view. These last are whitish and firmly fixed to the wing (this thin membrane also keeps the seed well attached to the scale during maturation); furthermore, among the typical distinctive features of the group, we have the micropylar fluid of the strobilus absent, no resin vesicles on the seeds[1] and the presence, in the vascular cylinder of the young root, of two characteristic small resiniferous canals. The bark and the wood of the genera Larix and Pseudotsuga have a similar anatomy and morphology: the reddish color of the heartwood and the white-yellowish of the sapwood, the high specific weight compared to other conifers, the distribution of late and earlywood, the presence of resiniferous channels and their localization in the tissuets, the molecules that form the resin and extractives, the chemical, physical and mechanical properties as well as the class of resistance to the attack of pathogens such as fungi and insects are a clue of a common ancestral origin.

Taxonomy

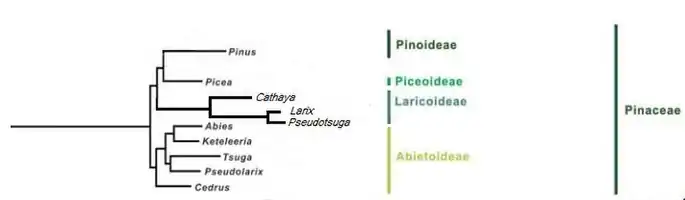

The subfamily Laricoideae was described with the actual name by Robert Knud Friedrich Pilger and Hans Melchior in late 1954[3] and subsequently modified by other authors in the course of time as regards the taxa of belonging. Before that, the genera Larix, Pseudotsuga and Cedrus were gathered in a provisional subfamily called Laricinae, defined for the first time by Melchior and Werdermann always in 1954 (...“trees that have both short and long shoots, monomorphic leaves, and strobili borne on the short shoots”...) and rechristened immediately after with the current term. The grouping in this form was confirmed by Hart (1987) through cladistic analysis, but already in 1988 Frankis replaced Cedrus with Cathaya (a genus described for the first time in 1962) in a new classification (now obsolete) that saw Larix as a distinct twin group compared to Cathaya - Pseudotsuga.

Historically the Laricoideae were the subfamily of the Pinaceae comprising the trees with needles inserted both on the macroblasts and on the brachiblasts; for this reason in the past they have been also included in it the genera Pseudolarix (for a short time) and Cedrus, subsequently eliminated following the most recent systematic updates developed on the basis of molecular genetic phylogeny, reproductive morphology, chromosome numbers and immunology. Currently, based on these studies, there are three genera in the subfamily Laricoideae, of which one of which is monotypic as it consists of only one species:[1]

| Image | Genus | Description | Living species |

|---|---|---|---|

| Larix Mill. | Larches are the genus type of this subfamily. Deciduous trees, they live in cold climates at elevate altitude in the mountains of temperate zones or at high latitudes in the Northern Hemisphere. They are found in North America, Central Europe and Northern Asia (Russia, Japan and China). |

|

| Pseudotsuga Carrière | Douglas-firs are medium to extremely large trees and often resemble morphologically as species of Abies or Tsuga. Have cones pendulous with persistent scales and three-pointed bract sticking out from the structure. They are found in the temperate mountains of North America and Eastern Asia, where they can reach 100 m in height (Pseudotsuga menziesii var. menziesii). |

|

| Cathaya Chun & Kuang | Monotypic genus with only one species: Cathaya argyrophylla. The leaves are needle-like, evergreen, 2.5–5 cm long with ciliates margins when young; they grow in spiral patterns around sprig. Cones 3–5 cm long with 15-20 scales, each scale bearing two winged seeds. This conifer grows in Southern China, in provinces of Guangxi, Guizhou, Hunan and southeast Sichuan on steep mountain slopes between the 950 and 1800 m of altitude. |

|

Within the subfamily the genera Larix and Pseudotsuga are more closely correlated to each other (sister taxon) than Cathaya. This evidence is demonstrated by numerous biological and morphological similarities between the larches and the Douglas-firs, including a various tissues common anatomy, immunology of seed protein and the absence of the two air sacs in the pollen, typicals instead of the other Pinaceae. The similarities between the pollen grains of the genera Larix and Pseudotsuga however do not stop here[5] and include other aspects as: granules not buoyant, atectate, with external wall (exospore) granular, pollination drop containing xylose[6] and the presence of an exine shell during microgametophyte germination. Doyle and O'Leary (1935)[5] furthermore described a pollination process very similar in Larix and Pseudotsuga where the granule, which lacks air sacs, lands on an almost stigmatic extension of the integument, the margins of which tend to inroll. The contact with the nucellus may (Larix) or may not (Pseudotsuga) be needed for pollen tubes to develop, but the mechanism is almost analogous. The time from pollination to fertilization in these two genera may be over a year and the granules germination can take months (Little et al., 2014).[5]

Price et al. he supposed in 1977 that the Laricoideae were a subfamily sister of the Abietoideae rather than the Pinoideae - Piceoideae group and this version was confirmed by Hart (1987), Frankis (1988), Farjon (1990), Wang et al. (2000) and Gernandt et al. (2008), although it has not yet found application in the literature.

Dichotomous key

The dichotomous key to recognizing the genera included to the subfamily Laricoideae is relatively simple, since only three of them belong to it and one of these is deciduous. Below is reported the taxonomic identification scheme in the form of a table:

|

1. Laricoideae (includes Larix, Pseudotsuga and Cathaya): 2

|

Revisions and research

According to the latest research still in progress,[7] the genus Cathaya would be attributed to the grouping of pines (subfamily Pinoideae), leaving therefore only Larix and Pseudotsuga to forming the subfamily Laricoideae. Furthermore, studying the mitochondrial rps3 gene, Ran et al. (2010)[5] found that Larix and Pseudotsuga are evolutionarily sister genera to all other Pinaceae, highlighting a different (sub-parallel) origin compared than the remaining species. Spellenberg, Earle and Nelson (2014)[8] report that the larches and Douglas firs evolved from the Pinaceae 135 million years ago and they kept a common ancestor until 7 million years ago, thus forming a divided and closely related taxonomic line between them compared to the rest of the group, while maintaining a strong degree of kinship with it. For Wang et al (2000)[9], instead, Pseudotsuga differentiated himself from Larix in Western North America about 65 million years ago, in an era between the late Cretaceous and the Paleocene. These revisions and interactions, which would find evidence in genetics, however are not universally accepted[1] and many botanics, researchers and scientists still use the previous classification waiting for further developments.

For other authors, finally, the subfamily Laricoideae would have no taxonomic dignity of its own, recognizing only two large multi-group clades (Pinoid and Abietoid[10]) or subfamilies (Pinoideae and Abietoideae[11]) in their classification systems. Larix, Pseudotsuga and Cathaya would be included in the pines complex.[11]

References

- Gymnosperm Database.

- "Douglas-fir: Tallest Tree in The World?". Vancouver Island Big Trees. Retrieved 2020-02-13.

- "Subfamily Laricoideae (Rendle) Pilger & Melchior". BioLib. Retrieved 2013-05-19.

- Farjon, A. (1990). Pinaceae: drawings and descriptions of the genera Abies, Cedrus, Pseudolarix, Keteleeria, Nothotsuga, Tsuga, Cathaya, Pseudotsuga, Larix and Picea. Königstein: Koeltz Scientific Books.

- Rudolphi, F. (2018-01-05). "Pinaceae". In Stephens, P. F. (ed.). Angiosperm Phylogeny Website, Version 14. Missouri Botanical Garden. Retrieved 2018-01-05.

- Nepi, M.; von Aderkas, P.; Wagner, R.; Mugnaini, S.; Coulter, A.; Pacini, E. (2009). "Nectar and pollination drops: how different are they?". Annals of Botany. 104 (2): 205–219. doi:10.1093/aob/mcp124. PMC 2710891. PMID 19477895.

- Lin, C. P.; Huang, J. P.; Wu, C. S.; Hsu, C. Y.; Chaw, S. M. (2010). "Comparative Chloroplast Genomics Reveals the Evolution of Pinaceae Genera and Subfamilies". Genome Biology and Evolution. 2: 504–517. doi:10.1093/gbe/evq036. PMC 2997556. PMID 20651328.

- Trees of Western North America. Princeton Field Guides. 2014. p. 106. ISBN 978-0-691-14580-8.

- XQ. Wang, Tank DC, Sang T. (2000). "Phylogeny and divergence times in Pinaceae: evidence from three genomes". Mol Biol Evol. 17: 773–781. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026356. PMID 10779538.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "Phylogeny and evolutionary history of Pinaceae updated by transcriptomic analysis". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 129: 106–116. 2018. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2018.08.011.

- Botanica Sistematica - Un Approccio Filogenetico. Italy: PICCIN. 2007. ISBN 978-88-299-1824-9.

Bibliography

- Pinaceae, Drawings and Descriptions of the Genera: Abies, Cedrus, Pseudolarix, Keteleeria, Nothotsuga, Tsuga, Cathaya, Pseudotsuga, Larix and Picea. Aljos Farjon. Koeltz Scientific Books, 1990 - 330 pages.

- Earle, Christopher J., ed. (2018). "Pinaceae". The Gymnosperm Database. Retrieved 2013-05-19.

- Lin, C. P; Huang, J. P; Wu, C. S; Hsu, C. Y; Chaw, S. M (2010). "Comparative Chloroplast Genomics Reveals the Evolution of Pinaceae Genera and Subfamilies". Genome Biology and Evolution. 2: 504–517. doi:10.1093/gbe/evq036. PMC 2997556. PMID 20651328.

External links

- Taxonomicon.nl Subfamily Laricoideae on taxonomicon.nl

- The Gymnosperm Database – Pinaceae (subfamily Laricoideae)

- Laricoideae in Pinaceae (Missouri Botanical Garden)

- Subfamily Laricoideae - (Rendle) Pilger & Melchior in BioLib.cz