Li Shanchang

Li Shanchang (Chinese: 李善長; pinyin: Lǐ Shàncháng; Wade–Giles: Li Shan-ch'ang; 1314-1390) was a chancellor of the Ming dynasty, part of the West Huai (Huaixi) faction, and one of the six dukes in 1370.[1] Li Shanchang was one of Emperor Hongwu's associates during the war against the Yuan dynasty to establish the Ming dynasty.[2]

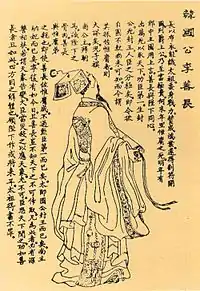

Li Shanchang 李善長 | |

|---|---|

Portrait of Li Shanchang | |

| Left Chancellor | |

| In office 1368–1371 | |

| Preceded by | position created |

| Succeeded by | Xu Da |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 1314 |

| Died | 1390 (aged 75–76) |

| Occupation | politician |

The emperor was "bored with Li's arrogance" in old age. The Zhu family emperor then purged and executed Li along with his extended family and thirty thousand others, accusing him of supporting treason.[3][4]

Li Shanchang organized ministries, helped draft a new law code, and helped compile the History of Yuan and the Ancestral Instructions and the Ritual Compendium of the Ming Dynasty. He helped established salt and tea monopolies based on Yuan institutions, launched an anti-corruption campaign to eliminate political opponents, restored minted currency, opened iron foundries, and instituted fish taxes. He made revenue by oppressing the people in the process.

He was a doubtful classicist, and was still charged with drafting legal documents, mandates, and military communications. The History of Ming biography states that his studies included Chinese Legalist writings. Most of his activities seem to have supported Hongwu Emperor's firm control of his regime. He was tasked with purging political opponents, anti-corruption, and rooting out disloyal military officers. His reward and punishment system was influenced by Han Feizi, and Li Shanchang had a kind of secret police in his service. At times he had charge of all civil and military officials in Nanjing.[5]

Life

| Part of a series on |

| Chinese legalism |

|---|

|

Li was a marginal figure in Dingyuan County until his recruitment by the Emperor Hongwu, who was passing through the area with his army. Li discussed history with him, namely, the qualities of the founding Han Emperor Gaozu of Han, and the emperor invited Li to take over the secretarial and managerial duties of his field command. He proved able and energetic, often staying behind to transfer army provisions. He was given first rank among officers with the titles of Grand Councilor of the Left and "Dynastic Duke of Han". Comparisons between the Emperor Hongwu and Gaozu became a theme of the Ming Court and its historians.[6]

One history holds that, after the navy in Chaohu surrendered to the emperor, Li urged ferrying the soldiers to capture the southern area of the Yangtze River. Then Li gave an advance notice to prevent the army from violating the military discipline. The duplicates of his notice were plastered everywhere in the occupied city, Taiping. Consequently, the troops garrisoned there in an orderly fashion.

The emperor asked Li to assume responsibility for administrative affairs in 1353,[7] granting him overall institutional authority long before codification work started. Li's petitioning Emperor Hongwu to eliminate collective prosecution reportedly initiated the drafting. Hongwu ordered Li and others to create the basic law code in 1367, appointing him Left Councilor and chief legislator in a commission of 30 ministers. Hongwu emphasized the importance of simplicity and clarity, and noted that the Tang dynasty and Song dynasty had fully developed criminal statutes, ignored by the Yuan dynasty. Li memorialized that all previous codes were based on the Han code, synthesized under the Tang, and based their institutions on the Tang Code.[8]

Following the drafting of the code, Li personally oversaw any new stipulations,[9] including a system of fixed statutes made to combat corruption.[10] He joined with Hu Weiyong against Yang Xian, another chancellor. Their efforts contributed to Yang's death, making Li the most powerful figure next to the emperor at the court in 1370. He quarreled with the great classical scholar Liu Bowen, causing the latter to resign from public office.[11]

Execution of Li and his family

In old age, he retired as the emperor's distaste grew for his arrogance, but would still be called upon to deliberate military and dynastic affairs. Other councilors like Guangyang, remembered his carefulness, generosity, honesty, uprightness and seriousness, was demoted several times. A lack of division of powers between the Emperor and his councilors resulted in conflicts, and the grand councilors (four total) gave up on state affairs, following prevailing affairs or doing nothing. Appointed to right councilor, Li gave himself over to drinking. He was ultimately implicated in 1390 in a decade-long conspiracy[12] and purged along with his extended family and thirty thousand others.[13] He was executed largely on the basis of his awareness and non-reporting of treason.[14] The post of councilor (or prime minister) was abolished following his execution.[15]

References

- Taylor, R. (1963) p.53p-54. SOCIAL ORIGINS OF THE MING DYNASTY 1351-1360. Monumenta Serica, 22(1), 1-78. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/40726467

- C. Simon Fan 2016. p.94. Culture, Institution, and Development in China. https://books.google.com/books?id=cwq4CwAAQBAJ&pg=PA94

- Anita M. Andrew, John A. Rapp 2000. p.161. Autocracy and China's Rebel Founding Emperors. https://books.google.com/books?id=YQOhVb5Fbt4C&pg=PA161

- Jiang Yonglin, Yonglin Jiang 2005. p.xxxiv. The Great Ming Code: Da Ming lü. https://books.google.com/books?id=h58hszAft5wC

- Taylor, R. (1963) p.53p-54. SOCIAL ORIGINS OF THE MING DYNASTY 1351-1360. Monumenta Serica, 22(1), 1-78. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/40726467

- Edward L. Farmer 1995 p.29. Zhu Yuanzhang and Early Ming Legislation. https://books.google.com/books?id=TCIjZ7l6TX8C&pg=PA29

- Frederick W. Mote 1999. p.550. Imperial China 900-1800. https://books.google.com/books?id=SQWW7QgUH4gC&pg=PA550

- Anita M. Andrew, John A. Rapp 2000. p.161. Autocracy and China's Rebel Founding Emperors. https://books.google.com/books?id=YQOhVb5Fbt4C&pg=PA161

- Edward L. Farmer 1995 p.29. Zhu Yuanzhang and Early Ming Legislation. https://books.google.com/books?id=TCIjZ7l6TX8C&pg=PA29

- Massey 1983

- Edward L. Farmer 1995 p.37. Zhu Yuanzhang and Early Ming Legislation. https://books.google.com/books?id=TCIjZ7l6TX8C&pg=PA37

- Jiang Yonglin, Yonglin Jiang 2005. p.xli, xliv, xlii. The Great Ming Code: Da Ming lü. https://books.google.com/books?id=h58hszAft5wC

- Jinfan Zhang 2014 p.282. The Tradition and Modern Transition of Chinese Law. https://books.google.com/books?id=AOu5BAAAQBAJ&pg=PA282

- Jinfan Zhang 2014 p.168. The Tradition and Modern Transition of Chinese Law. https://books.google.com/books?id=AOu5BAAAQBAJ&pg=PA168

- Edward L. Farmer 1995 p.37. Zhu Yuanzhang and Early Ming Legislation. https://books.google.com/books?id=TCIjZ7l6TX8C&pg=PA37

- Taylor, R. (1963) p.53p-54. SOCIAL ORIGINS OF THE MING DYNASTY 1351-1360. Monumenta Serica, 22(1), 1-78. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/40726467

- Edward L. Farmer 1995 p.58. Zhu Yuanzhang and Early Ming Legislation. https://books.google.com/books?id=TCIjZ7l6TX8C&pg=PA58

- Anita M. Andrew, John A. Rapp 2000. p.148,61,167-168. Autocracy and China's Rebel Founding Emperors. https://books.google.com/books?id=YQOhVb5Fbt4C&pg=PA161

- C. Simon Fan 2016. p.94. Culture, Institution, and Development in China. https://books.google.com/books?id=cwq4CwAAQBAJ&pg=PA94

- James Tong 1991 p.230. Disorder Under Heaven: Collective Violence in the Ming Dynasty. https://books.google.com/books?id=PnPQ25Oh2yUC&pg=PA230