Lika

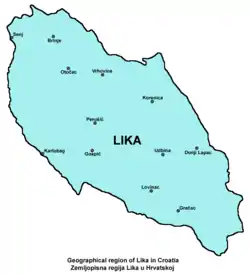

Lika (Croatian: [lǐːka]) is a traditional region[2] of Croatia proper, roughly bound by the Velebit mountain from the southwest and the Plješevica mountain from the northeast. On the north-west end Lika is bounded by Ogulin-Plaški basin, and on the south-east by the Malovan pass. Today most of the territory of Lika (Brinje, Donji Lapac, Gospić, Lovinac, Otočac, Perušić, Plitvička Jezera, Udbina and Vrhovine) is part of Lika-Senj County. Josipdol, Plaški and Saborsko are part of Karlovac County and Gračac is part of Zadar County.

Lika | |

|---|---|

Approximate region of Lika within Croatia | |

| Country | |

| Largest city | Gospić |

| Area | |

| • Total | 5,283 km2 (2,040 sq mi) |

| Population (2011) | |

| • Total | 50,927 |

| • Density | 9.6/km2 (25/sq mi) |

| • Total % of Croatia | 1.19% |

| • Ethnic groups | Croats 84.15%Serbs 13.65% |

| Demonym(s) | Licaners |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | CEST |

Major towns include Gospić, Otočac, and Gračac, most of which are located in the karst poljes of the rivers of Lika, Gacka and others. The Plitvice Lakes National Park is also in Lika.

History

Antiquity

Since the first millennium BC the region was inhabited by Iapydes, an ancient people related to Illyrians. During the Gallic invasion of the Balkans, a division of the Gallic army passed through the territory of today's Lika and a part of this army settled among the Iapydes.

In the 2nd century BC, Iapydes came into conflict with the Roman Empire, suffering several military campaigns, most significantly in 129 BC, 119 BC and finally being conquered in 34 BC by Augustus Caesar.[3]

Medieval

Bijelohrvati (or White Croats) originally migrated from White Croatia to Lika in the first half of the 7th century. After the settlement of Croats (according to migrations theories), Lika became part of the Principality of Littoral Croatia. Lika then became a part of the Kingdom of Croatia in 925, when Duke Tomislav of the Croats received the crown and became King of Croatia.

The name of Lika is derived from old Illyrian language, meaning "body of water"; its cognates are liquor ("fluid") in Latin and liqén ("lake") in modern Albanian. Indeed, a major feature of the Lika landscape are rivers and lakes, as well as marshes and floodplains, many of which have been drained in 18th to 20th centuries. The name initially referred to Lika River, and over time came to denote the region.[4] The first mention of Lika as a toponym appears in 10th-century Constantine Porphyrogenitus' book De Administrando Imperio as βο(ε)άνος, in a chapter dedicated to Croats and the organisation of their state, describing how their ban "has under his rule Krbava, Lika and Gacka".[5][6]

Among the twelve noble Croat tribes that had a right to choose the Croat king, the Gusić tribe was from Lika.

From the 15th century

.svg.png.webp)

In 1493 the Croatian army suffered a heavy defeat from the Ottoman forces in the Battle of Krbava Field, near Udbina in Lika. As the Ottomans advanced into Croatia, the Croatian population from the region gradually started to move into safer parts of the country or abroad.[7] Many indigenous Chakavians of Lika leaving this area and to their places mainly arriving Neo-Shtokavian Ikavians from western Hezegovina and western Bosnia, and Orthodox (Vlachs and Serbs Neo-Shtokavian Ijekavians) from south-east of Balkan Peninsula.[8] In 1513 the town of Modruš, the location of the episcopal see in Lika, was overrun by the Ottomans.[9] In 1527 they captured Udbina, leaving most of Lika under Ottoman control.[10] The region became initially part Sanjak of Bosnia, later the Sanjak of Klis and finally the Sanjak of Krka. The devastation of Lika and Krbava was such that almost half a century they remained largely uninhabited. At the end of the 16th century the Ottomans started settling Vlachs in the area, as well as Muslims in larger settlements where they soon formed a majority of the population.[11]

Prince Radic was appointed Prince of Senj by King Rudolf in Graz (1 December 1600). Radic family is a Native noble family from Lika region; members of the family were Uskok military leaders at the headquarters in Senj. Prince of Senj was very active against Ottoman. In 1683 after Ottoman defeat at the battle of Vienna, 30,000 Muslims from Lika began to move towards Bosnia. Large number of these Muslims originated from Bosnia from which they came a century earlier, while a substantial proportion was of Croatian origin.[12]

The Ottoman rule in Lika mostly ended in 1689 with the recapture of Udbina. However area of Donji Lapac remained in Ottoman hands for 102 years.[13] The borders between the Habsburg Monarchy and the Ottoman Empire were initially concluded with the Treaty of Karlowitz in 1699,[14] finally concluded with Treaty of Sistova in 1791. Lika was incorporated into the Karlovac general command of the Croatian Military Frontier. It was repopulated by immigrants from Ottoman held regions. Catholics predominated in urban settlements, while Orthodox Christians were mostly present in the interior of Lika.[15]

On 15 July 1881 the Military Frontier was abolished, and Lika was restored to Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia, an autonomous part of Transleithania (the Hungarian part of the Dual Monarchy of Austro-Hungary). It was within the Lika-Krbava County, with Gospić as the county seat. Its population was ethnically mixed and in 1910 consisted of 50.8% Serbs and 49% Croats.[16]

Kingdom of Yugoslavia to SFRY

After the collapse of Austria-Hungary, Croatia and Slavonia, of which Lika was part, became part of the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs on October 29, 1918. The newly created state then joined the Kingdom of Serbia on December 1, 1918 to form Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes which was in 1929 renamed into Yugoslavia. Lika remained inside Croatia, which became one of the constituent provinces of the Kingdom. The majority of Lika belonged to the Županija Lika-Krbava with the capital in Senj (instead of in Gospić previously). The new constitution abolished any previous borders and Lika became a part of the Primorsko-krajiška Oblast with the capital in Karlovac. In 1929, the region became a part of the Sava Banate (Savska banovina) of the newly formed Kingdom of Yugoslavia, and then in 1939 of the Croatian Banate (Hrvatska banovina).

Yugoslavia was invaded and split by the Axis forces in 1941 and Lika became a part of the Independent State of Croatia (NDH), an Axis puppet state led by the Ustaše that systematically slaughtered Serbs during World War II.[17] On 27 July the Srb uprising started against the Ustaše in Lika, led by Yugoslav Partisans and Chetniks, accompanied with mass crimes against Croats in the region.[18] In June 1943 the founding session of the State Anti-fascist Council for the National Liberation of Croatia (ZAVNOH) was held in Otočac in Lika, in the territory held by the Partisans.[19] The war ended in 1945 and Croatia became a Socialist federal unit of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia.

Croatian War of Independence

In August 1990 an insurrection known as Log Revolution started in Serb populated areas of Croatia. Due to recent civil unrest and with Croatia declaring independence from Yugoslavia in June 1991, the Serb majority settlements of eastern Lika joined with fellow Serbian populace in Croatia in the creation and declaration of independence of the Republic of Serbian Krajina (RSK). Subsequently, the Serbian paramilitary units were created with the backing of the Yugoslav National Army and Serbian paramilitary forces. Clashes with the Croatian police that followed later in 1991 quickly erupted in a full-scale war. The fiercest fighting in Lika took place during the Battle of Gospić in August and September 1991 that resulted in the seat of the province being heavily damaged by the Serbian forces. Western Lika remained under Croatian control, while eastern Lika was under RSK control.[20] War continued until 1995, when the Croatian Army took over the region in Operation Storm, ending the existence of the RSK.

After the war, a number of towns and municipalities in the region were designated Areas of Special State Concern.

Economy

Lika is traditionally a rural area with a developed farming (growing potatoes) and livestock. Industry is minimal and relies mostly on wood processing. The non-contamination could prove a major advantage in the near future based and tourism development. For this there are great potentials – Like in the two national parks (Plitvice Lakes and Sjeverni Velebit), are important factors and proximity to Dalmatian summer resorts and good transport links.

Culture

Lika has a distinct culture. The Ikavian and Shtokavian dialects of the Croatian language are both spoken in most of Lika, and Chakavian is spoken in the North around the town of Brinje.

Lika caps are worn by the local men and farmers informally at home, and also formally at weddings and celebrations.

Cuisine

.jpg.webp)

The cuisine of Lika is shaped by its mountainous terrain, scarcity of arable land, cold winters, and the extensive practice of animal husbandry. It is simple, traditional and hearty, heavily focused on fresh, local ingredients and home style cooking.[21] Maize, potatoes, lamb and dairy products form the basis of the local diet. Meat is commonly salted or dried, while on special occasions a whole lamb is roasted on a large skewer. Common meat products include šunka (ham), pršut (prosciutto), kulin (blood sausage) and žmare (čvarci). Dairy products such as butter, skorup and cheeses are abundant. Basa is a common cheese variety made from fermented milk and skorup. Trout is farmed and used extensively in many varieties, smoked, marinated or breaded in corn flour and fried. Trout caviar is local delicacy. The use of vegetables is limited, and mostly consists of cabbage, turnips and beans.

Common dishes include:

- Polenta - Eaten in many varieties, with skorup, žmare or sour cabbage.

- Stewed beans - Usually enriched with sour cabbage, turnip or bacon.

- Lički lonac (Lika pot) - A hearty, complex stew of mutton and various vegetables (potatoes, fresh cabbage, carrots, celery, parsley, bell peppers, tomatoes, etc.). Commonly eaten with boiled potatoes or polenta on the side.

- Lamb under a peka - Lamb and potatoes cooked in a peka, a large metal or ceramic lid.

- Sour cabbage with cured meat - Usually includes cured mutton, bacon, kulin, and potatoes on the side.

Common desserts include štrudla (savijača), ruffled dough stuffed with cheese or grated apples, and uštipci, deep fried nuggets of sweetened leavened dough.[22]

Population

The 2011 census data for Lika-Senj County shows 50,927 inhabitants,[24] which is a decrease from the 53,677[25] inhabitants counted in 2001 (this is a drop of about 5.1% over the ten years and continues a decades-long depopulation trend in Lika). In 2011, 84.15% of the residents were of Croat, and 13.65% of Serb ethnicity.[24]

Notable people

- Jovanka Broz

- Mile Budak

- Matija Čanić

- Josip Čorak

- Marko Došen

- Josip Filipović

- Jure Francetić

- Milovan Gavazzi

- Stjepan Jovanović

- Ana Karić

- Ivan Karlović

- Vinko Knežević

- Edo Kovačević

- Ferdinand Kovačević

- Miroslav Kraljević

- Priest Martinac

- Marko Mesić

- Darko Milinović

- Veljko Narančić

- Nicholas of Modruš

- Ante Nikšić

- Omar Pasha

- Mirjan Pavlović

- Ivica Rajković

- Ivan Rukavina

- Mathias Rukavina von Boynograd

- Sandra Šarić

- Stjepan Sarkotić

- Martin Sekulić

- Tomislav Sertić

- Franjo Šimić

- Petar Smiljanić

- Ante Starčević

- David Starčević

- Šime Starčević

- Rade Šerbedžija

- Nikola Tesla

- Nikica Valentić

- Josef Philipp Vukassovich

- Janko Vuković

- Josif Rajačić

- Božidar Maljković

References

- Pejnović 2009, p. 82.

- Pejnović 2009, p. 54.

- Luka Pavičić and collaborators, 1987, Lovinac Monografija. pp. 47.-48.

- Pejnović 2009, pp. 57–60.

- De Administrando Imperio 30/90-117, "καὶ ὁ βοάνος αὐτῶν κρατεῖ τὴν Κρίβασαν, τὴν Λίτζαν καὶ τὴν Γουτζησκά"

- Pejnović 2009, p. 57.

- Goldstein 1999, pp. 30–31.

- Šimunović 2010, p. 223.

- Tanner 1997, p. 31.

- Tanner 1997, p. 37.

- Mažuran 1998, p. 197.

- Florian Bieber; (2000) Muslim Identity in the Balkans before the Establishment of Nation States p.20; Cambridge University Press,

- Mažuran 1998, p. 242.

- Mažuran 1998, p. 254.

- Tanner 1997, p. 60.

- "KlimoTheca :: Könyvtár" (in Hungarian). Kt.lib.pte.hu. Retrieved 2012-12-06.

- Goldstein 1999, p. 137.

- Cooke, Philip; Shepherd, Ben H. (2013). European Resistance in the Second World War. Pen and Sword. p. 222. ISBN 9781473833043.

- Goldstein 1999, p. 148.

- Tanner 1997, p. 277.

- "Lika Gastro". Retrieved 13 January 2019.

- "TOP 10 jela koja trebate probati u Lici". Retrieved 13 January 2019.

- "Croatian national park overwhelmed by selfie-taking tourists". The Daily Telegraph. 13 July 2016. Retrieved 27 December 2018.

- "Population by Ethnicity, by Towns/Municipalities, 2011 Census: County of Lika-Senj". Census of Population, Households and Dwellings 2011. Zagreb: Croatian Bureau of Statistics. December 2012.

- https://www.dzs.hr/Eng/censuses/Census2001/Popis/E01_01_01/e01_01_01_zup09.html

Bibliography

- Goldstein, Ivo (1999). Croatia: A History. McGill-Queen's Press.

- Mažuran, Ive (1998). Povijest Hrvatske od 15. stoljeća do 18. stoljeća (in Croatian). Zagreb: Golden marketing.

- Pejnović, Dane (2009). "Geografske osnove identiteta Like" [The geographical foundations of the Lika identity] (PDF). In Holjevac, Željko (ed.). Identitet Like: korijeni i razvitak (in Croatian). 1. Institute of Social Sciences Ivo Pilar – Regional Center Gospić. pp. 47–84. ISBN 978-953-6666-65-2. Retrieved 27 December 2018.

- Šimunović, Petar (2010). "Lička toponomastička stratigrafija" [Toponomastic and linguistic stratigraphy in Lika] (PDF). Folia onomastica Croatica (in Croatian) (19): 223–246. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- Tanner, Marcus (1997). Croatia – a nation forged in war. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-06933-2.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lika. |