Lithosphere

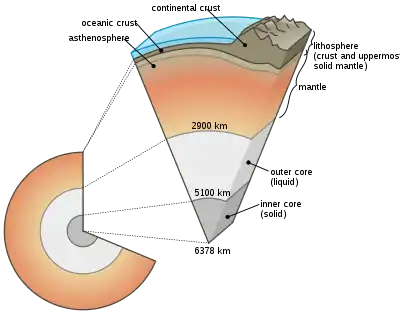

A lithosphere (Ancient Greek: λίθος [líthos] for "rocky", and σφαίρα [sfaíra] for "sphere") is the rigid,[1] outermost shell of a terrestrial-type planet or natural satellite. On Earth, it is composed of the crust and the portion of the upper mantle that behaves elastically on time scales of thousands of years or greater. The crust and upper mantle are distinguished on the basis of chemistry and mineralogy.

Earth's lithosphere

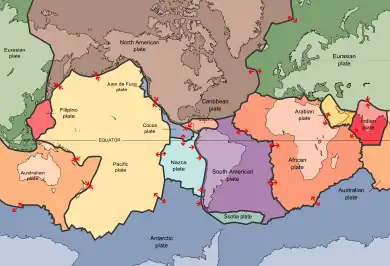

Earth's lithosphere includes the crust and the uppermost mantle, which constitutes the hard and rigid outer layer of the Earth. The lithosphere is subdivided into tectonic plates. The lithosphere is underlain by the asthenosphere which is the weaker, hotter, and deeper part of the upper mantle. The Lithosphere-Asthenosphere boundary is defined by a difference in response to stress: the lithosphere remains rigid for very long periods of geologic time in which it deforms elastically and through brittle failure, while the asthenosphere deforms viscously and accommodates strain through plastic deformation.

The thickness of the lithosphere is thus considered to be the depth to the isotherm associated with the transition between brittle and viscous behavior.[2] The temperature at which olivine becomes ductile (~1000 °C) is often used to set this isotherm because olivine is generally the weakest mineral in the upper mantle.[3]

History of the concept

The concept of the lithosphere as Earth's strong outer layer was described by A.E.H. Love in his 1911 monograph "Some problems of Geodynamics" and further developed by Joseph Barrell, who wrote a series of papers about the concept and introduced the term "lithosphere".[4][5][6][7] The concept was based on the presence of significant gravity anomalies over continental crust, from which he inferred that there must exist a strong, solid upper layer (which he called the lithosphere) above a weaker layer which could flow (which he called the asthenosphere). These ideas were expanded by Reginald Aldworth Daly in 1940 with his seminal work "Strength and Structure of the Earth."[8] They have been broadly accepted by geologists and geophysicists. These concepts of a strong lithosphere resting on a weak asthenosphere are essential to the theory of plate tectonics.

Types

The lithosphere can be divided into oceanic and continental lithosphere. Oceanic lithosphere is associated with oceanic crust (having a mean density of about 2.9 grams per cubic centimeter) and exists in the ocean basins. Continental lithosphere is associated with continental crust (having a mean density of about 2.7 grams per cubic centimeter) and underlies the continents and continental shelfs.[9]

Oceanic lithosphere

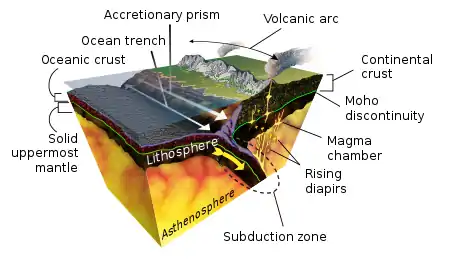

Oceanic lithosphere consists mainly of mafic crust and ultramafic mantle (peridotite) and is denser than continental lithosphere. Young oceanic lithosphere, found at mid-ocean ridges, is no thicker than the crust, but oceanic lithosphere thickens as it ages and moves away from the mid-ocean ridge. The oldest cceanic lithosphere is typically about 140 km thick.[3] This thickening occurs by conductive cooling, which converts hot asthenosphere into lithospheric mantle and causes the oceanic lithosphere to become increasingly thick and dense with age. In fact, oceanic lithosphere is a thermal boundary layer for the convection[10] in the mantle. The thickness of the mantle part of the oceanic lithosphere can be approximated as a thermal boundary layer that thickens as the square root of time.

Here, is the thickness of the oceanic mantle lithosphere, is the thermal diffusivity (approximately 10−6 m2/s) for silicate rocks, and is the age of the given part of the lithosphere. The age is often equal to L/V, where L is the distance from the spreading centre of mid-oceanic ridge, and V is velocity of the lithospheric plate.[11]

Oceanic lithosphere is less dense than asthenosphere for a few tens of millions of years but after this becomes increasingly denser than asthenosphere. While chemically differentiated oceanic crust is lighter than asthenosphere, thermal contraction of the mantle lithosphere makes it more dense than the asthenosphere. The gravitational instability of mature oceanic lithosphere has the effect that at subduction zones, oceanic lithosphere invariably sinks underneath the overriding lithosphere, which can be oceanic or continental. New oceanic lithosphere is constantly being produced at mid-ocean ridges and is recycled back to the mantle at subduction zones. As a result, oceanic lithosphere is much younger than continental lithosphere: the oldest oceanic lithosphere is about 170 million years old, while parts of the continental lithosphere are billions of years old.[12][13]

Subducted lithosphere

Geophysical studies in the early 21st century posit that large pieces of the lithosphere have been subducted into the mantle as deep as 2900 km to near the core-mantle boundary,[14] while others "float" in the upper mantle.[15][16] Yet others stick down into the mantle as far as 400 km but remain "attached" to the continental plate above,[13] similar to the extent of the "tectosphere" proposed by Jordan in 1988.[17] Subducting lithosphere remains rigid (as demonstrated by deep earthquakes along Wadati–Benioff zone) to a depth of about 600 km (370 mi).[18]

Continental lithosphere

Continental lithosphere has a range in thickness from about 40 km to perhaps 280 km;[3] the upper ~30 to ~50 km of typical continental lithosphere is crust. The crust is distinguished from the upper mantle by the change in chemical composition that takes place at the Moho discontinuity. The oldest parts of continental lithosphere underlie cratons, and the mantle lithosphere there is thicker and less dense than typical; the relatively low density of such mantle "roots of cratons" helps to stabilize these regions.[19][13]

Because of its relatively low density, continental lithosphere that arrives at a subduction zone cannot subduct much further than about 100 km (62 mi) before resurfacing. As a result, continental lithosphere is not recycled at subduction zones the way oceanic lithosphere is recycled. Instead, continental lithosphere is a nearly permanent feature of the Earth.[20][21]

Mantle xenoliths

Geoscientists can directly study the nature of the subcontinental mantle by examining mantle xenoliths[22] brought up in kimberlite, lamproite, and other volcanic pipes. The histories of these xenoliths have been investigated by many methods, including analyses of abundances of isotopes of osmium and rhenium. Such studies have confirmed that mantle lithospheres below some cratons have persisted for periods in excess of 3 billion years, despite the mantle flow that accompanies plate tectonics.[23]

See also

References

- Skinner, B.J. & Porter, S.C.: Physical Geology, page 17, chapt. The Earth: Inside and Out, 1987, John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 0-471-05668-5

- Parsons, B. & McKenzie, D. (1978). "Mantle Convection and the thermal structure of the plates" (PDF). Journal of Geophysical Research. 83 (B9): 4485. Bibcode:1978JGR....83.4485P. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.708.5792. doi:10.1029/JB083iB09p04485.

- Pasyanos M. E. (2008-05-15). "Lithospheric Thickness Modeled from Long Period Surface Wave Dispersion" (PDF). Retrieved 2014-04-25.

- Barrell, J (1914). "The strength of the Earth's crust". Journal of Geology. 22 (4): 289–314. Bibcode:1914JG.....22..289B. doi:10.1086/622155. JSTOR 30056401. S2CID 118354240.

- Barrell, J (1914). "The strength of the Earth's crust". Journal of Geology. 22 (5): 441–468. Bibcode:1914JG.....22..441B. doi:10.1086/622163. JSTOR 30067162. S2CID 224833672.

- Barrell, J (1914). "The strength of the Earth's crust". Journal of Geology. 22 (7): 655–683. Bibcode:1914JG.....22..655B. doi:10.1086/622181. JSTOR 30060774. S2CID 224832862.

- Barrell, J (1914). "The strength of the Earth's crust". Journal of Geology. 22 (6): 537–555. Bibcode:1914JG.....22..537B. doi:10.1086/622170. JSTOR 30067883. S2CID 128955134.

- Daly, R. (1940) Strength and structure of the Earth. New York: Prentice-Hall.

- Philpotts, Anthony R.; Ague, Jay J. (2009). Principles of igneous and metamorphic petrology (2nd ed.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 2–4, 29. ISBN 9780521880060.

- Donald L. Turcotte, Gerald Schubert, Geodynamics. Cambridge University Press, 25 mar 2002 - 456

- Stein, Seth; Stein, Carol A. (1996). "Thermo-Mechanical Evolution of Oceanic Lithosphere: Implications for the Subduction Process and Deep Earthquakes". Subduction: 1–17. doi:10.1029/GM096p0001.

- Jordan, Thomas H. (1978). "Composition and development of the continental tectosphere". Nature. 274 (5671): 544–548. Bibcode:1978Natur.274..544J. doi:10.1038/274544a0. S2CID 4286280.

- O'Reilly, Suzanne Y.; Zhang, Ming; Griffin, William L.; Begg, Graham; Hronsky, Jon (2009). "Ultradeep continental roots and their oceanic remnants: A solution to the geochemical "mantle reservoir" problem?". Lithos. 112: 1043–1054. Bibcode:2009Litho.112.1043O. doi:10.1016/j.lithos.2009.04.028.

- Burke, Kevin; Torsvik, Trond H. (2004). "Derivation of Large Igneous Provinces of the past 200 million years from long-term heterogeneities in the deep mantle". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 227 (3–4): 531. Bibcode:2004E&PSL.227..531B. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2004.09.015.

- Replumaz, Anne; Kárason, Hrafnkell; Van Der Hilst, Rob D; Besse, Jean; Tapponnier, Paul (2004). "4-D evolution of SE Asia's mantle from geological reconstructions and seismic tomography". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 221 (1–4): 103–115. Bibcode:2004E&PSL.221..103R. doi:10.1016/S0012-821X(04)00070-6.

- Li, Chang; Van Der Hilst, Robert D.; Engdahl, E. Robert; Burdick, Scott (2008). "A new global model for P wave speed variations in Earth's mantle". Geochemistry Geophysics Geosystems. 9 (5): n/a. Bibcode:2008GGG.....905018L. doi:10.1029/2007GC001806.

- Jordan, T. H. (1988). "Structure and formation of the continental tectosphere". Journal of Petrology. 29 (1): 11–37. Bibcode:1988JPet...29S..11J. doi:10.1093/petrology/Special_Volume.1.11.

- Frolich, C. (1989). "The Nature of Deep Focus Earthquakes". Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences. 17: 227–254. Bibcode:1989AREPS..17..227F. doi:10.1146/annurev.ea.17.050189.001303.

- Jordan, Thomas H. (1978). "Composition and development of the continental tectosphere". Nature. 274 (5671): 544–548. Bibcode:1978Natur.274..544J. doi:10.1038/274544a0. S2CID 4286280.

- Ernst, W. G. (June 1999). "Metamorphism, partial preservation, and exhumation of ultrahigh‐pressure belts". Island Arc. 8 (2): 125–153. doi:10.1046/j.1440-1738.1999.00227.x.

- Stern 2002, p. 1.

- Nixon, P.H. (1987) Mantle xenoliths J. Wiley & Sons, 844 p. ISBN 0-471-91209-3

- Carlson, Richard W. (2005). "Physical, chemical, and chronological characteristics of continental mantle" (PDF). Reviews of Geophysics. 43 (1): RG1001. Bibcode:2005RvGeo..43.1001C. doi:10.1029/2004RG000156. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-11-22.

Further reading

- Chernicoff, Stanley; Whitney, Donna (1990). Geology. An Introduction to Physical Geology (4th ed.). Pearson. ISBN 978-0-13-175124-8.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lithospheres. |