Longleaf pine

The longleaf pine (Pinus palustris) is a pine species native to the Southeastern United States, found along the coastal plain from East Texas to southern Maryland, extending into northern and central Florida.[2] It reaches a height of 30–35 m (98–115 ft) and a diameter of 0.7 m (28 in). In the past, before extensive logging, they reportedly grew to 47 m (154 ft) with a diameter of 1.2 m (47 in). The tree is a cultural symbol of the Southern United States, being the official state tree of Alabama.[3] Contrary to popular belief, this particular species of pine is not officially the state tree of North Carolina.[4]

| Longleaf pine | |

|---|---|

| |

| Longleaf pine (Pinus palustris) forest | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Division: | Pinophyta |

| Class: | Pinopsida |

| Order: | Pinales |

| Family: | Pinaceae |

| Genus: | Pinus |

| Subgenus: | P. subg. Pinus |

| Section: | P. sect. Trifoliae |

| Subsection: | P. subsect. Australes |

| Species: | P. palustris |

| Binomial name | |

| Pinus palustris | |

| |

Description

The bark is thick, reddish-brown, and scaly.[5][6] The leaves are dark green and needle-like, and occur in bundles of mainly three, sometimes two or four, especially in seedlings. They often are twisted and 20–45 cm (7.9–17.7 in) in length. It is one of the two Southeastern U.S. pines with long needles, the other being slash pine.

The cones, both female seed cones (ovulate strobili) and male pollen cones (staminate strobili), are initiated during the growing season before buds emerge. Pollen cones begin forming in their buds in July, while seed conelets are formed during a relatively short period of time in August. Pollination occurs early the following spring, with the male cones 3–8 cm (1.2–3.1 in) long. The female (seed) cones mature in about 20 months from pollination; when mature, they are yellow-brown in color, 15–25 cm (5.9–9.8 in) long, and 5–7 cm (2.0–2.8 in) broad, opening to 12 cm (4.7 in), and have a small, but sharp, downward-pointing spine on the middle of each scale. The seeds are 7–9 mm (0.28–0.35 in) long, with a 25–40 mm (0.98–1.57 in) wing.

Longleaf pine takes 100 to 150 years to become full size and may live to be 500 years old. When young, they grow a long taproot, which usually is 2–3 m (6.6–9.8 ft) long; by maturity, they have a wide spreading lateral root system with several deep 'sinker' roots. They grow on well-drained, usually sandy soil, characteristically in pure stands.[7] Longleaf pine also is known as being one of several species grouped as a southern yellow pine[8] or longleaf yellow pine, and in the past as pitch pine (a name dropped as it caused confusion with pitch pine, Pinus rigida).

Etymology

The species epithet palustris is Latin for "of the marsh" and indicates its common habitat.[9] The scientific name meaning "of marshes" is a misunderstanding on the part of Philip Miller, who described the species, after seeing longleaf pine forests with temporary winter flooding.

Ecology

Longleaf pine is highly pyrophytic (resistant to wildfire). Their thick bark helps to provide a tolerance to fire.[10] Periodic natural wildfire selects for this species by killing other trees, leading to open longleaf pine forests or savannas. New seedlings do not appear at all tree-like and resemble a dark-green fountain of needles. This form is called the grass stage. During this stage, which lasts for 5–12 years, vertical growth is very slow, and the tree may take a number of years simply to grow ankle high. After that, it has a growth spurt, especially if no tree canopy is above it. In the grass stage, it is very resistant to low intensity fires because the terminal bud is protected from lethal heating by the tightly packed needles. While relatively immune to fire at this stage, the plant is quite appealing to feral pigs; the early settlers' habit of releasing swine into the woodlands to feed may have been partly responsible for the decline of the species.

Longleaf pine forests are rich in biodiversity. They are well-documented for their high levels of plant diversity, in groups including sedges, grasses, carnivorous plants, and orchids.[11][12] These forests also provide habitat for gopher tortoises, which as keystone species, dig burrows that provide habitat for hundreds of other species of animals. The red-cockaded woodpecker is dependent on mature pine forests and is now endangered as a result of this decline. Longleaf pine seeds are large and nutritious, forming a significant food source for birds (notably the brown-headed nuthatch) and other wildlife. Nine salamander species and 26 frog species are characteristic of pine savannas, along with 56 species of reptiles, 13 of which could be considered specialists on this habitat.[13]

The Red Hills Region of Florida and Georgia is home to some of the best-preserved stands of longleaf pines. These forests have been burned regularly for many decades to encourage bobwhite quail habitat in private hunting plantations.

Uses

Vast forests of longleaf pine once were present along the southeastern Atlantic coast and Gulf Coast of North America, as part of the eastern savannas. These forests were the source of naval stores - resin, turpentine, and timber - needed by merchants and the navy for their ships. They have been cutover since for timber and usually replaced with faster-growing loblolly pine and slash pine, for agriculture, and for urban and suburban development. Due to this deforestation and overharvesting, only about 3% of the original longleaf pine forest remains, and little new is planted. Longleaf pine is available, however, at many nurseries within its range; the southernmost known point of sale is in Lake Worth, Florida.

The yellow, resinous wood is used for lumber and pulp. Boards cut years ago from virgin timber were very wide, up to 1 m (3.3 ft), and a thriving salvage business obtains these boards from demolition projects to be reused as flooring in upscale homes.

The extremely long needles are popular for use in the ancient craft of coiled basket making.

The stumps and taproots of old trees become saturated with resin and will not rot. Farmers sometimes find old buried stumps in fields, even in some that were cleared a century ago, and these usually are dug up and sold as fatwood, "fat lighter", or "lighter wood", which is in demand as kindling for fireplaces, wood stoves, and barbecue pits. In old-growth pine, the heartwood of the bole is often saturated in the same way. When boards are cut from the fat lighter wood, they are very heavy and will not rot, but buildings constructed of them are quite flammable and make extremely hot fires.

The seeds of the longleaf pine are edible raw or roasted.[14]

Cultural significance

The longleaf pine is the official state tree of Alabama.[15] It is commonly but incorrectly believed to be the official state tree of North Carolina, probably because it is referenced by name in the first line of the official North Carolina State Toast.[4][16] Also, the state's highest honor is named the "Order of the Long Leaf Pine". However, the state tree of North Carolina is officially designated as simply "pine", not any particular species of pine.[4][17]

Native range, restoration, and protection

Before European settlement, longleaf pine forest dominated as much as 90,000,000 acres (360,000 km2) stretching from Virginia south to Florida and west to East Texas. Its range was defined by the frequent widespread fires that occurred throughout the southeast. In the late 19th century, these virgin timber stands were "among the most sought-after timber trees in the country." This rich ecosystem now has been relegated to less than 5% of its presettlement range due to clear-cutting practices:

As they stripped the woods of their trees, loggers left mounds of flammable debris that frequently fueled catastrophic fires, destroying both the remaining trees and seedlings. The exposed earth left behind by clear-cutting operations was highly susceptible to erosion, and nutrients were washed from the already porous soils. This further destroyed the natural seeding process. At the peak of the timber cutting in the 1890s and first decade of the new century, the longleaf pine forests of the Sandhills were providing millions of board feet of timber each year. The timber cutters gradually moved across the South; by the 1920s, most of the "limitless" virgin longleaf pine forests were gone.

- — Jerry Simmons, "ASLC Large Operation from Beginnings"[18]

In "pine barrens" most of the day. Low, level, sandy tracts; the pines wide apart; the sunny spaces between full of beautiful abounding grasses, liatris, long, wand-like solidago, saw palmettos, etc., covering the ground in garden style. Here I sauntered in delightful freedom, meeting none of the cat-clawed vines, or shrubs, of the alluvial bottoms.

Efforts are being made to restore longleaf pine ecosystems within its natural range. Some groups such as the Longleaf Alliance are actively promoting research, education, and management of the longleaf pine.[19]

The USDA offers cost-sharing and technical assistance to private landowners for longleaf restoration through the NRCS Longleaf Pine Initiative. Similar programs are available through most state forestry agencies in the longleaf's native range. In August 2009, the Alabama Forestry Commission received $1.757 million in stimulus money to restore longleaf pines in state forests.[20]

Four large core areas within the range of the species provide the opportunity to protect the biological diversity of the coastal plain and to restore wilderness areas east of the Mississippi River.[21] Each of these four (Eglin Air Force Base: 187,000+ ha; Apalachicola National Forest: 228,000+ ha; Okefenokee-Osceola: 289,000+ ha; De Soto National Forest: 200,000+ ha) have nearby lands that offer the potential to expand the total protected territory for each area to well beyond 500,000 ha. These areas would provide the opportunity not only to restore forest stands, but also to restore populations of native vertebrate animals threatened by landscape fragmentation.

Notable eccentric populations exist within the Uwharrie National Forest in the central Piedmont region of North Carolina. These have survived owing to relative inaccessibility, and in one instance, intentional protection in the 20th century by a private landowner (a property now owned and conserved by the LandTrust for Central North Carolina).

The United States Forest Service is conducting prescribed burning programs in the 258,864-acre Francis Marion National Forest, located outside of Charleston, South Carolina. They are hoping to increase the longleaf pine forest type to 44,700 acres (181 km2) by 2017 and 53,500 acres (217 km2) in the long term. In addition to longleaf restoration, prescribed burning will enhance the endangered red-cockaded woodpeckers' preferred habitat of open, park-like stands, provide habitat for wildlife dependent on grass-shrub habitat, which is very limited, and reduce the risk of damaging wildfires.[22]

Since the 1960s, longleaf restoration has been ongoing on almost 95,000 acres of state and federal land in the sandhills region of South Carolina, between the piedmont and coastal plain. The region is characterized by deep, infertile sands deposited by a prehistoric sea, with generally arid conditions. By the 1930s, most of the native longleaf had been logged, and the land was heavily eroded. Between 1935 and 1939, the federal government purchased large portions of this area from local landowners as a relief measure under the Resettlement Administration. These landowners were resettled on more fertile land elsewhere. Today, the South Carolina Sand Hills State Forest comprises about half of the acreage, and half is owned by the United States Fish and Wildlife Service as the adjacent Carolina Sandhills National Wildlife Refuge. At first, restoration of forest cover was the goal. Fire suppression was practiced until the 1960s, when prescribed fire was introduced on both the state forest[23] and the Sandhills NWR[24][25] as part of the restoration of the longleaf/wiregrass ecosystem.

Nokuse Plantation is a 53,000-acre private nature preserve located around 100 miles east of Pensacola, Florida. The preserve was established by M.C. Davis, a wealthy philanthropist who made his fortune buying and selling land and mineral rights, and who has spent $90 million purchasing land for the preserve, primarily from timber companies. One of its main goals is the restoration of longleaf pine forest, to which end he has had 8 million longleaf pine seedlings planted on the land.[26]

A 2009 study by the National Wildlife Federation says that longleaf pine forests will be particularly well adapted to environmental changes caused by climate disruption. [27]

See also

- Longleaf pine ecosystem

- Mountain Longleaf National Wildlife Refuge

- Sonderegger pine, a hybrid between loblolly and longleaf species

References

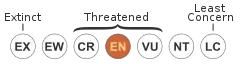

- Farjon, A. (2013). "Pinus palustris". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2013: e.T39068A2886222. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2013-1.RLTS.T39068A2886222.en.

- "Longleaf Pine Range Map". The Longleaf Alliance. Archived from the original on 25 November 2015. Retrieved 25 November 2015.

- "Official Emblems and Symbols, Tree, Southern Longleaf Pine". archives.alabama.gov. Alabama Department of Archives and History. Archived from the original on 8 August 2014. Retrieved 16 September 2020.

- Case, Steven (2011). "State Tree of North Carolina: Pine". NCPedia. Retrieved 6 July 2020.

- Thomas M. Bonnicksen (7 February 2000). America's Ancient Forests: From the Ice Age to the Age of Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 234. ISBN 978-0-471-13622-4.

- William Carey Grimm (1 March 2002). Illustrated Book of Trees: The Comprehensive Field Guide to More than 250 Trees of Eastern North America. Stackpole Books. p. 181. ISBN 978-0-8117-4164-4.

- Richard Edwin McArdle (1930). The Yield of Douglas Fir in the Pacific Northwest. U.S. Department of Agriculture. p. 5.

Longleaf pine in both the virgin forest and second growth is characteristically a tree of pure stand—one in which 80 per cent or more of the trees are of a single species.

- Moore, Gerry; Kershner, Bruce; Craig Tufts; Daniel Mathews; Gil Nelson; Spellenberg, Richard; Thieret, John W.; Terry Purinton; Block, Andrew (2008). National Wildlife Federation Field Guide to Trees of North America. New York: Sterling. p. 75. ISBN 978-1-4027-3875-3.

- Archibald William Smith A Gardener's Handbook of Plant Names: Their Meanings and Origins, p. 258, at Google Books

- "Longleaf Pine Forests". www.nclongleaf.org. Retrieved 2 October 2020.

- Peet, R. K. and D. J Allard. 1993. Longleaf pine vegetation of the southern Atlantic and eastern Gulf coast regions: a preliminary classification. pp. 45–81. In S. M. Hermann (ed.) Proceedings of the Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference. No. 18. The Longleaf Pine Ecosystem: Ecology, Restoration, and Management. Florida: Tall Timbers Research Station.

- Keddy, P.A., L. Smith, D.R. Campbell, M. Clark and G. Montz. 2006. Patterns of herbaceous plant diversity in southeastern Louisiana pine savannas. Applied Vegetation Science 9:17-26.

- Means, D. Bruce. 2006. Vertebrate faunal diversity in longleaf pine savannas. Pages 155-213 in S. Jose, E. Jokela and D. Miller (eds.) Longleaf Pine Ecosystems: Ecology, Management and Restoration. Springer, New York. xii + 438 pp.

- Deuerling, Dick; Lantz, Peggy (Winter 1990). "Nuts to You!" (PDF). The Palmetto. 10 (4): 13 – via Florida Native Plant Society.

- "Southern Longleaf Pine". Official Symbols and Emblems of Alabama. Retrieved 4 April 2009.

- North Carolina General Statutes § 149‑2 http://www.ncleg.net/enactedlegislation/statutes/html/bysection/chapter_149/gs_149-2.html

- "§ 145-3". www.ncleg.net.

- Simmons, Jerry (2009). "ASLC Large Operation from Beginnings" (PDF). Retrieved 28 October 2019.

- "Longleaf Pine Forests and Longleaf Alliance Home". Longleaf Alliance. Retrieved 4 April 2009.

- "Stimulus to fund repopulation of longleaf pines in Alabama". The Birmingham News. Archived from the original on 6 October 2012. Retrieved 1 September 2009.

- Keddy, P.A. 2009. Thinking big: A conservation vision for the Southeastern coastal plain of North America. Southeastern Naturalist 8: 213-226.

- "Fiscal Year 2006 Monitoring and Evaluation Annual Report" (PDF). Francis Marion National Forest. United States Forest Service. 26 September 2007. Retrieved 16 June 2009.

- "SCFC Sand Hills". www.state.sc.us.

- "Carolina Sandhills NWR History".

- "Refuge to Begin Conducting Prescribed Burns in February" (PDF). United States Fish and Wildlife Service. Retrieved 14 December 2011.

- Block, Melissa (17 June 2015). "Gambler-Turned-Conservationist Devotes Fortune To Florida Nature Preserve". All Things Considered. NPR. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- "Restoring roots of Southeast: Environmental benefits, quality of wood touted". The (Charleston, SC) Post and Courier. 12 December 2009. Archived from the original on 9 April 2010. Retrieved 12 December 2009.

Further reading

- "A Toast" to North Carolina., January 1957, retrieved 4 April 2009

- Vanderbilt University, Department of Biological Sciences. "Bioimages - Pinus palustris". Bioimages. Archived from the original on 7 June 2011. Retrieved 4 April 2009.

- "Pinus palustris description". The Gymnosperm Database. Retrieved 4 April 2009.

- Pinus palustris description, retrieved 4 April 2009

- "Pinus palustris in Flora of North America @ efloras.org". Flora of North America. Retrieved 4 April 2009.

- Pinus palustris in Flora of North America @ efloras.org, retrieved 4 April 2009

- State tree, January 1963, retrieved 4 April 2009

- "Tall Timbers". Retrieved 4 April 2009.

- Outcalt, Kenneth W. (2000). "The Longleaf Pine Ecosystem of the South". Native Plants Journal. 1 (1): 42–53. doi:10.3368/npj.1.1.42.

- Ashe, William Willard (1897). The Forests, Forest Lands, and Forest Products of Eastern North Carolina. J. Daniels. Retrieved 4 April 2009.

eastern north carolina forests.

- "North Carolina Cooperative Extension Service - Reforestation of North Carolina's Pines". 14 August 2007. Archived from the original on 12 July 1997. Retrieved 4 April 2009.

- "Longleaf pine/wiregrass ecosystem". Carolina Sandhills National Wildlife Refuge. Retrieved 4 April 2009.

- Barnett, James P. (2014). Direct Seeding Southern Pines: History and Status of a Technique Developed for Restoring Cutover Forests. Asheville, NC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Southern Research Station. Retrieved 27 July 2014.

External links

Media related to Pinus palustris at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Pinus palustris at Wikimedia Commons