Tallahassee, Florida

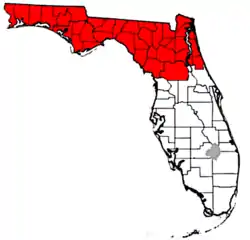

Tallahassee (/ˌtæləˈhæsi/) is the capital city of the U.S. state of Florida. It is the county seat and only incorporated municipality in Leon County. Tallahassee became the capital of Florida, then the Florida Territory, in 1824. In 2019, the population was 194,500, making it the 8th-largest city in the U.S state of Florida, and the 126th-largest city in the United States.[5] The population of the Tallahassee metropolitan area was 385,145 as of 2018. Tallahassee is the largest city in the Florida Big Bend and Florida Panhandle region, and the main center for trade and agriculture in the Florida Big Bend and Southwest Georgia regions.

Tallahassee, Florida | |

|---|---|

State capital of Florida | |

| City of Tallahassee | |

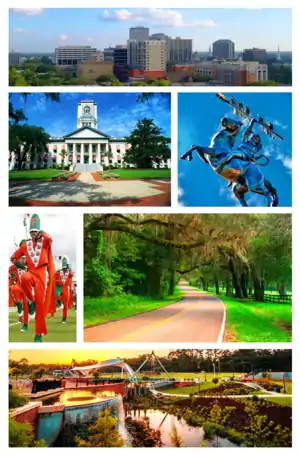

Top, Left to Right: Tallahassee Skyline, Florida Capitol Buildings, Unconquered statue of Osceola and Renegade at FSU, FAMU's Marching 100, Old St. Augustine Canopy Road, and Cascades Park | |

Seal | |

| Motto(s): "Florida's Capital City" | |

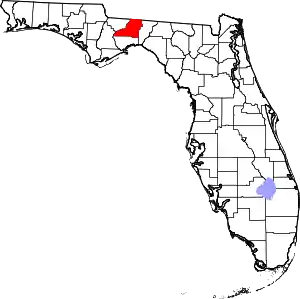

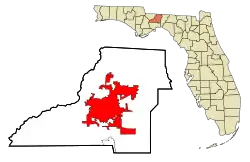

Location within Leon County and the state of Florida | |

Tallahassee Location within Florida  Tallahassee Location within the United States  Tallahassee Location within North America | |

| Coordinates: 30°27′18″N 84°15′12″W | |

| Country | |

| State | Florida |

| County | Leon |

| Established | 1824 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Commission–Manager |

| • Mayor | John Dailey (D) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 103.70 sq mi (268.57 km2) |

| • Land | 100.49 sq mi (260.27 km2) |

| • Water | 3.21 sq mi (8.30 km2) |

| Elevation | 203 ft (62 m) |

| Population (2010)[3] | |

| • Total | 181,376 |

| • Estimate (2019)[4] | 194,500 |

| • Rank | 126th, U.S. |

| • Density | 1,935.52/sq mi (747.30/km2) |

| • Urban | 240,223 (153rd) |

| • Metro | 385,145 (140th) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| ZIP code(s) | 32300–32399 |

| Area code(s) | 850 |

| FIPS code | 12-70600[3] |

| GNIS feature ID | 308416 |

| Website | www |

Tallahassee is home to Florida State University, ranked the nation's eighteenth best public university by U.S. News & World Report.[6] It is also home to Florida A&M University, the fifth-largest historically black university by total enrollment.[7] Tallahassee Community College is a large state college that serves mainly as a feeder school to Florida State and Florida A&M. Tallahassee qualifies as a significant college town, with a student population exceeding 70,000.[8]

As the capital, Tallahassee is the site of the Florida State Capitol, Supreme Court of Florida, Florida Governor's Mansion, and nearly 30 state agency headquarters. The city is also known for its large number of law firms, lobbying organizations, trade associations and professional associations, including the Florida Bar and the Florida Chamber of Commerce.[9] It is a recognized regional center for scientific research, and home to the National High Magnetic Field Laboratory. In 2015, Tallahassee was awarded the All-American City Award by the National Civic League for the second time.

History

Indigenous peoples occupied this area for thousands of years before European encounter. Around AD 1200, the large and complex Mississippian culture had built earthwork mounds near Lake Jackson which survive today; they are preserved in the Lake Jackson Archaeological State Park.[10]

The Spanish Empire established their first colonial settlement at St. Augustine. During the 17th century they established several missions in Apalachee territory to procure food and labor to support their settlement, as well as to convert the natives to Roman Catholicism. The largest, Mission San Luis de Apalachee in Tallahassee, has been partially reconstructed by the state of Florida.

The expedition of Pánfilo de Narváez encountered the Apalachee people, although it did not reach the site of Tallahassee. Hernando de Soto and his mid-16th century expedition occupied the Apalachee town of Anhaica (at what is now Tallahassee) in the winter of 1538–1539. Based on archaeological excavations, this Anhaica site is now known to have been about 0.5 miles (800 m) east of the present Florida State Capitol. The De Soto encampment is believed to be the first place Christmas was celebrated in the continental United States although there is no historical documentation to back this claim.[11]

The name "Tallahassee" is a Muskogean language word often translated as "old fields" or "old town".[12] It was likely an expression of the Creek people who migrated from Georgia and Alabama to this region in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, under pressure from European-American encroachment on their territory. They found large areas of cleared land previously occupied by the Apalachee tribe. (The Creek and later refugees who joined them developed as the Seminole Indians of Florida.)

During the First Seminole War, General Andrew Jackson fought two separate skirmishes in and around Tallahassee, which was then Spanish territory. The first battle took place on November 12, 1817. After Chief Neamathla, of the village of Fowltown just west of present-day Tallahassee, refused Jackson's orders to relocate. Jackson entered the village, burnt it to the ground, and drove off its occupants. The Indians retaliated, killing 50 soldiers and civilians. Jackson reentered Florida in March 1818. According to Jackson's adjutant, Colonel Robert Butler, they "advanced on the Indian village called Tallahasse (sic) [where] two of the enemy were made prisoner."[13]

State capital

Florida became an American territory in September 1821, in accordance with the Adams-Onís Treaty of 1819.

The first session of the Legislative Council of the Territory of Florida met on July 22, 1822, at Pensacola, the former capital of West Florida. Members from St. Augustine, the former capital of East Florida, traveled 59 days by water to attend. The second session was in St. Augustine, and western delegates needed 28 days to travel perilously around the peninsula to reach St. Augustine. During this session, delegates decided to hold future meetings at a halfway point. Two appointed commissioners selected Tallahassee, at that point an Apalachee settlement (Anhaica) virtually abandoned after Andrew Jackson burned it in 1818, as a halfway point. In 1824 the third legislative session met there in a crude log building serving as the capitol.[14]

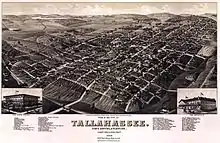

From 1821 through 1845, during Florida's territorial period, the rough-hewn frontier capital gradually developed as a town. The Marquis de Lafayette, French hero of the American Revolution, returned to the United States in 1824 for a tour. The U.S. Congress voted to give him $200,000 (the same amount he had given the colonies in 1778), US citizenship, and the Lafayette Land Grant, 36 square miles (93 km2) of land that today includes large portions of Tallahassee. In 1845 a Greek revival masonry structure was erected as the Capitol building in time for statehood. Now known as the "old Capitol", it stands in front of the high-rise Capitol building built in the 1970s.[15]

Tallahassee was in the heart of Florida's Cotton Belt—Leon County led the state in cotton production—and was the center of the slave trade in Florida.[16] During the American Civil War, Tallahassee was the only Confederate state capital east of the Mississippi River not captured by Union forces, and the only one not burned. A small engagement, the Battle of Natural Bridge, was fought south of the city on March 6, 1865, just a month before the war ended.

During the 19th century, the institutions that would develop into what is now Florida State University were established in Tallahassee; it became a university town. These included the Tallahassee Female Academy (founded 1843) and the Florida Institute (founded 1854). In 1851, the Florida legislature decreed two seminaries to be built on either side of the Suwannee River, East Florida Seminary and West Florida Seminary. In 1855 West Florida Seminary was transferred to the Florida Institute building (which had been established as an inducement for the state to place the seminary in Tallahassee). In 1858, the seminary absorbed the Tallahassee Female Academy and became coeducational.[17] Its main building was near the northwest corner of South Copeland and West Jefferson streets, approximately where FSU's Westcott Building is today.

In 1887, the Normal College for Colored Students, the ancestor of today's FAMU, opened its doors. The legislature decided Tallahassee was the best location in Florida for a college serving African-American students; the state had segregated schools. Four years later its name was changed to State Normal and Industrial College for Colored Students, to teach teachers for elementary school children and students in industrial skills.

After the Civil War much of Florida's industry moved to the south and east, a trend that continues today. The end of slavery and the rise of free labor reduced the profitability of the cotton and tobacco trade, at a time when world markets were also changing. The state's major industries shifted to citrus, lumber, naval stores, cattle ranching, and tourism. The latter was increasingly important by the late 19th century. In the post-Civil War period, many former plantations in the Tallahassee area were purchased by wealthy northerners for use as winter hunting preserves. This included the hunting preserve of Henry L. Beadel, who bequeathed his land for the study of the effects of fire on wildlife habitat. Today the preserve is known as the Tall Timbers Research Station and Land Conservancy, nationally recognized for its research into fire ecology and the use of prescribed burning.

1900–present

Until World War II, Tallahassee remained a small southern town with virtually the entire population living within one mile (1.6 km) of the Capitol. The main economic drivers were the colleges and state government, where politicians met to discuss spending money on grand public improvement projects to accommodate growth in places such as Miami and Tampa Bay, hundreds of miles away from the capital.

Tallahassee was also active in protest during the civil rights era. The Tallahassee bus boycott was a citywide boycott in Tallahassee, Florida that sought to end racial segregation in the employment and seating arrangements of city buses. On May 26, 1956, Wilhemina Jakes and Carrie Patterson, two Florida A&M University students, were arrested by the Tallahassee Police Department for "placing themselves in a position to incite a riot". Robert Saunders, representing the NAACP, and Rev. C. K. Steele began talks with city authorities while the local African-American community started boycotting the city's buses. The Inter-Civic Council ended the boycott on December 22, 1956. On January 7, 1957, the City Commission repealed the bus-franchise segregation clause because of the United States Supreme Court ruling Browder v. Gayle (1956). In the 1960s there was a movement to transfer the capital to Orlando, closer to the state's growing population centers. That movement was defeated; the 1970s saw a long-term commitment by the state to the capital city, with the construction of the new capitol complex and preservation of the old Florida State Capitol building.

In 1970, the Census Bureau reported the city's population as 74.0% white and 25.4% black.[18] In 1971, the city elected James R. Ford to the 5-member City Commission and he became the city's first African-American mayor in 1972 (commissioners rotated into the position serving a one-year term).

Bobby Bowden became the head coach of Florida State Seminoles football in 1976, and turned Tallahassee into a city dominated by college football, Bowden became very successful very quickly at Florida State. By his second year, Bowden had to deny many rumors that he would leave for another job; the team went 9–2, compared to the four wins total in the three seasons before Bowden. During 34 years as head coach he had only one losing season–his first, in 1976.

In 1977 a 22-story high-rise Capitol building designed by architect Edward Durell Stone was completed, which is now the third-tallest state capitol building in the United States. In 1978 the old capitol, directly in front of the new capitol, was scheduled for demolition, but state officials decided to keep the Old Capitol as a museum.[19] In 1986, Jack McLean served as mayor, the second African-American to hold the position.[20]

Tallahassee was the center of world attention for six weeks during the 2000 United States Presidential election recount, which involved numerous rulings by the Florida Secretary of State and the Florida Supreme Court.

In 2016, the city suffered a direct hit by Hurricane Hermine, causing about 80% of the city proper to lose power, including Florida State University, and knocking down many trees.[21]

In 2018, the city suffered another natural disaster when Hurricane Michael hit the panhandle.

Geography

.jpg.webp)

[22] Tallahassee has an area of 98.2 square miles (254.3 km2), of which 95.7 square miles (247.9 km2) is land and 2.5 square miles (6.5 km2) (2.59%) is water.

Tallahassee's terrain is hilly by Florida standards, being at the southern end of the Red Hills Region, just above the Cody Scarp. The elevation varies from near sea level to just over 200 feet (61 m), with the state capitol on one of the highest hills in the city. The city includes two large lake basins, Lake Jackson and Lake Lafayette, and borders the northern end of the Apalachicola National Forest.

The flora and fauna are similar to those found in the mid-south and low country regions of South Carolina and Georgia. The palm trees are the more cold-hardy varieties like the state tree, the Sabal palmetto. Pines, magnolias, hickories, and a variety of oaks are the dominant trees. The Southern Live Oak is perhaps the most emblematic of the city.

Nearby cities and suburbs

Cityscape

Neighborhoods

Tallahassee has many neighborhoods inside the city limits. Some of the most known and defined include All Saints, Apalachee Ridge, Betton Hills, Buck Lake, Callen, Frenchtown (the oldest historically black neighborhood in the state), Killearn Estates, Killearn Lakes Plantation, Lafayette Park, Levy Park, Los Robles, Midtown, Holly Hills, Jake Gaither/University Park, Indian Head Acres, Myers Park, Smokey Hollow, SouthWood, Seminole Manor and Woodland Drives.

Tallahassee is also home to some gated communities, including Golden Eagle, Ox Bottom, Lafayette Oaks and The Preserve at San Luis; the Tallahassee Ranch Club is to the southeast of the city.

Tallest buildings

| Rank | Name | Street Address | Height feet | Height meters | Floors | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Florida State Capitol | 400 South Monroe Street, | 345 | 101 | 25 | 1977[23] |

| 2 | Turlington Building | 325 West Gaines Street, | 318 | 97 | 19 | 1990 |

| 3 | Plaza Tower | 300 South Duval Street | 276 | 84 | 24 | 2008 |

| 4 | Highpoint Center | 100 South Adams St | 239 | 70 | 15 | 1990 |

| 5 | DoubleTree Hotel | 101 South Adams St, | 220 | 67 | 17 | 1972 |

Urban planning and expansion

The first plan for the Capitol Center was the 1947 Taylor Plan, which consolidated several government buildings in one downtown area. In 1974, the Capitol Center Planning Commission for the City of Tallahassee, Florida responded to growth of its urban center with a conceptual plan for the expansion of its Capitol Center. Hisham Ashkouri, working for The Architects' Collaborative, led the urban planning and design effort. Estimating growth and related development for approximately the next 25 years, the program projected the need for 2.3 million square feet (214,000 m2) of new government facilities in the city core, with 3,500 dwelling units, 100 acres (40 ha) of new public open space, retail and private office space, and other ancillary spaces. Community participation was an integral part of the design review, welcoming Tallahassee residents to provide input as well as citizens' groups and government agencies, resulting in the creation of six separate design alternatives.

Sprawl and compact growth

The Tallahassee-Leon County Planning Department implements policies aimed at promoting compact growth and development, including the establishment and maintenance of an Urban Service Area. The intent of the Urban Service Area is to "have Tallahassee and Leon County grow in a responsible manner, with infrastructure provided economically and efficiently, and surrounding forest and agricultural lands protected from unwarranted and premature conversion to urban land use."[24] The result of compact growth policies has been a significant overall reduction in the Sprawl Index for Tallahassee between 2000 and 2010.[25] CityLab reported on this finding, stating "Tallahassee laps the field, at least as far as the Sprawl Index is concerned."[26]

Climate

| Tallahassee | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Tallahassee has a humid subtropical climate (Köppen Cfa), with long summers and short, mild winters, as well as drier springs and autumns. Summer maxima here are hotter than in the Florida peninsula and it is one of the few cities in the state to occasionally record temperatures above 100 °F or 37.8 °C, averaging 2.4 days annually.[27] The record high of 105 °F (41 °C) was set on June 15, 2011.[28]

Summer is characterized by brief intense showers and thunderstorms that form along the afternoon sea breeze from the Gulf of Mexico. The daily mean temperature in July, the hottest month, is 82.0 °F (27.8 °C). Conversely, the city is markedly cooler in the winter, with a January daily average temperature of 51.2 °F (10.7 °C).[27] The city averages 32 nights with a minimum at or below freezing, and on average, the window for freezing temperatures is from November 20 thru March 21, allowing a growing season of 243 days.[27] As Tallahassee is part of USDA Hardiness Zone 8b,[29] each winter's coldest temperature is typically slightly below 20 °F (−7 °C); readings below 15 °F (−9 °C) are very rare, having last occurred on January 11, 2010.[27] During the Great Blizzard of 1899 the city reached −2 °F (−19 °C) on February 13, which remains Florida's only recorded reading below 0 °F (−18 °C). At the time, Tallahassee's record low was colder than the record low in either Ketchikan, Alaska, or Tromsø, Norway. The record cold daily maximum is 22 °F (−6 °C), set on the same day as the all-time record low, while conversely, the record warm daily minimum is 81 °F (27 °C) on July 15, 1980.[27]

Snow and ice are rare in Tallahassee. Historically, the city usually records at least flurries every three to four years, but snowfall of 1 inch (2.5 cm) or more occurs only once every 17 years on average. The closest location that receives regular yearly snowfalls is Macon, Georgia, 200 miles (320 km) north of Tallahassee. Nonetheless, Tallahassee has recorded a few accumulating snowfalls over the last 100 years; the heaviest snowfall was 2.8 inches (7 cm) on February 13, 1958.[30] Tallahassee's other recorded measurable snowfalls were 1.0 inch (2.5 cm) on February 12–13, 1899, and December 22–23, 1989; 0.4 inches (1.0 cm) on March 28, 1955, and February 10, 1973; 0.2 inches (0.5 cm) on February 2, 1951; and 0.1 inches (0.3 cm) on January 3, 2018.[30][31][32]

Although several hurricanes have brushed Tallahassee with their outer rain and wind bands, in recent years only Hurricane Kate, in 1985, and Hurricane Hermine, in 2016, have struck Tallahassee directly. Hurricane Michael passed 50 miles to the west after making landfall near Mexico Beach, Florida in October 2018 as a Category 5 storm, resulting in 95% of Leon County being without power.

The Big Bend area of North Florida sees several tornadoes each year during the season, but they are generally weak, cause little structural damage, and rarely hit the city. On April 19, 2015, a tornado touched down in Tallahassee. The tornado was rated EF1, and created a path as wide as 350 yards (320 m) for almost 5 miles (8 km) near Maclay Gardens.[33] Damage included numerous downed tree limbs and a car crushed by a falling tree. During extremely heavy rains, some low-lying parts of Tallahassee may flood, notably the Franklin Boulevard area adjacent to the downtown and the Killearn Lakes subdivision, outside the Tallahassee city limits, on the north side.

The most recent tornado to hit Tallahassee occurred on January 27, 2021. It was rated as EF0 tornado. The tornado caused damage to the city and the Tallahassee International Airport. [34]

| Climate data for Tallahassee International Airport, Florida (1981–2010 normals,[35] extremes 1892–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 83 (28) |

89 (32) |

91 (33) |

95 (35) |

102 (39) |

105 (41) |

104 (40) |

103 (39) |

102 (39) |

95 (35) |

89 (32) |

84 (29) |

105 (41) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 77.7 (25.4) |

80.0 (26.7) |

85.2 (29.6) |

89.8 (32.1) |

94.7 (34.8) |

97.6 (36.4) |

98.7 (37.1) |

97.6 (36.4) |

95.1 (35.1) |

90.3 (32.4) |

84.0 (28.9) |

79.0 (26.1) |

99.7 (37.6) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 63.5 (17.5) |

67.5 (19.7) |

73.8 (23.2) |

79.9 (26.6) |

87.0 (30.6) |

91.0 (32.8) |

92.1 (33.4) |

91.5 (33.1) |

88.4 (31.3) |

81.4 (27.4) |

73.0 (22.8) |

65.3 (18.5) |

79.5 (26.4) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 51.2 (10.7) |

54.7 (12.6) |

60.4 (15.8) |

66.1 (18.9) |

74.3 (23.5) |

80.2 (26.8) |

82.0 (27.8) |

81.8 (27.7) |

78.2 (25.7) |

69.4 (20.8) |

60.2 (15.7) |

53.2 (11.8) |

67.6 (19.8) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 39.0 (3.9) |

41.9 (5.5) |

47.1 (8.4) |

52.3 (11.3) |

61.6 (16.4) |

69.5 (20.8) |

72.0 (22.2) |

72.1 (22.3) |

68.1 (20.1) |

57.3 (14.1) |

47.5 (8.6) |

41.1 (5.1) |

55.8 (13.2) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 19.9 (−6.7) |

23.6 (−4.7) |

27.9 (−2.3) |

34.9 (1.6) |

47.9 (8.8) |

61.2 (16.2) |

66.6 (19.2) |

65.7 (18.7) |

54.3 (12.4) |

37.4 (3.0) |

29.5 (−1.4) |

22.8 (−5.1) |

17.7 (−7.9) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 6 (−14) |

−2 (−19) |

20 (−7) |

29 (−2) |

34 (1) |

46 (8) |

57 (14) |

57 (14) |

40 (4) |

29 (−2) |

13 (−11) |

10 (−12) |

−2 (−19) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 4.34 (110) |

4.85 (123) |

5.94 (151) |

3.06 (78) |

3.47 (88) |

7.73 (196) |

7.17 (182) |

7.35 (187) |

4.69 (119) |

3.23 (82) |

3.50 (89) |

3.90 (99) |

59.23 (1,504) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01-inch) | 8.9 | 8.4 | 7.9 | 6.1 | 7.1 | 13.6 | 16.0 | 14.4 | 8.5 | 5.7 | 6.6 | 8.1 | 111.3 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 186 | 197.8 | 248 | 300 | 310 | 300 | 279 | 279 | 240 | 248 | 210 | 186 | 2,983.8 |

| Mean daily sunshine hours | 6.0 | 7.0 | 8.0 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 9.0 | 9.0 | 8.0 | 8.0 | 7.0 | 6.0 | 8.2 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 60 | 64 | 67 | 77 | 71 | 71 | 64 | 69 | 67 | 73 | 64 | 60 | 67 |

| Source 1: NOAA[27][36] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Weather Atlas[37] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Tallahassee | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily daylight hours | 10.0 | 11.0 | 12.0 | 13.0 | 14.0 | 14.0 | 14.0 | 13.0 | 12.0 | 11.0 | 11.0 | 10.0 | 12.1 |

| Average Ultraviolet index | 4 | 6 | 8 | 10 | 10 | 11 | 11 | 10 | 9 | 7 | 5 | 4 | 7.9 |

| Source: Weather Atlas [37] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1840 | 1,616 | — | |

| 1860 | 1,932 | — | |

| 1870 | 2,023 | 4.7% | |

| 1880 | 2,494 | 23.3% | |

| 1890 | 2,934 | 17.6% | |

| 1900 | 2,981 | 1.6% | |

| 1910 | 5,018 | 68.3% | |

| 1920 | 5,637 | 12.3% | |

| 1930 | 10,700 | 89.8% | |

| 1940 | 16,240 | 51.8% | |

| 1950 | 27,237 | 67.7% | |

| 1960 | 48,174 | 76.9% | |

| 1970 | 72,624 | 50.8% | |

| 1980 | 81,548 | 12.3% | |

| 1990 | 124,773 | 53.0% | |

| 2000 | 150,624 | 20.7% | |

| 2010 | 181,376 | 20.4% | |

| 2019 (est.) | 194,500 | [4] | 7.2% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[38] | |||

| Tallahassee Demographics | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 Census | Tallahassee | Leon County | Florida |

| Total population | 181,376 | 275,487 | 18,801,310 |

| Population, percent change, 2000 to 2010 | +20.4% | +15.0% | +17.6% |

| Population density | 1,809.3/sq mi | 413.1/sq mi | 350.6/sq mi |

| White or Caucasian (including White Hispanic) | 57.4% | 63.0% | 75.0% |

| (Non-Hispanic White or Caucasian) | 53.3% | 59.3% | 57.9% |

| Black or African-American | 35.0% | 30.3% | 16.0% |

| Hispanic or Latino (of any race) | 6.3% | 5.6% | 22.5% |

| Asian | 3.7% | 2.9% | 2.4% |

| Native American or Native Alaskan | 0.2% | 0.3% | 0.4% |

| Pacific Islander or Native Hawaiian | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.1% |

| Two or more races (Multiracial) | 2.3% | 2.2% | 2.5% |

| Some Other Race | 1.3% | 1.5% | 3.6% |

As of the 2010 census, the population of Tallahassee was estimated to be 181,376. There were 74,815 households, 21.3% of which had children under 18 living in them. 27.7% were married couples living together, 14.4% had a female householder with no husband, and 53.7% were non-families. 34.1% of all households were made up of individuals living alone and 6.7% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.23 and the average family size was 2.88. Children under the age of 5 were 5.5% of the population, persons under 18 were 17.2%, and persons 65 years or older were 8.1%. The median age was 26 years. For every 100 females, there were 89.5 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 86.7 males.

57.4% of the population was White, 35.0% Black, 3.7% Asian, 0.2% American Indian and Alaska Native, 0.1% Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander, 1.3% some other race, and 2.3% two or more races. 6.3% were Hispanic or Latino of any race, and 53.3% were non-Hispanic White. For 2009–2013, the estimated median household income was $39,524, and the per capita income was $23,778.

The percentage of persons below the poverty level was estimated at 30.2%.[39]

Educationally, the population of Leon County is the most highly educated population in Florida[40] with 54.4% of the residents over the age of 25 with a Bachelor's, Master's, professional or doctorate degree.[41] The Florida average is 37.4%[40] and the national average is 33.4%.[42]

Languages

As of 2000, 91.99% of residents spoke English as their first language, while 4.11% spoke Spanish, 0.63% spoke French, and 0.59% spoke German as their mother tongue. In total, 8.00% of the total population spoke languages other than English.[43]

Law, government and politics

Politics

Tallahassee has traditionally been a Democratic city, but the party has been supported by different ethnic groups over time, with a major shift in the late 20th century. Leon County has voted Democratic in 24 of the past 29 presidential elections since 1904. But until the late 1960s, most African Americans were disenfranchised from the political system, dating from a new constitution and other laws passed by conservative Democratic whites in Florida (and in all other Southern states) at the turn of the century. At that time, most African Americans were affiliated with the Republican Party, and their disenfranchisement resulted in that party being non-competitive in the region for decades. Subsequently, these demographic groups traded party alignments.

Since passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and enforcement of constitutional rights for African Americans, voters in Tallahassee have elected black mayors and black state representatives.[44]:97 It has become a city in the Southern U.S. that is known for progressive activism. This is likely due to the large student population that attends Florida State University, Florida A&M University, and Tallahassee Community College. In addition, in the realignment of party politics since the late 20th century, most of the significant African-American population in the city now support Democratic Party candidates.[45][46]

As of December 2, 2018, there were 112,572 Democrats, 58,083 Republicans, and 44,007 voters who were independent or had other affiliations among the 214,662 voters in Leon County.[47]

Leon County's voter turnout percentage has consistently ranked among the highest of Florida's 67 counties, with a record-setting 86% turnout in the November 2008 general election. The county voted for Barack Obama in the presidential election.[48]

Structure of city government

Tallahassee has a form of government with an elected mayor of Tallahassee, elected commissioners, and an at-will employed city manager, city departments, and staff.

The current city commissioners are:[49]

- Seat 1 – Jacqueline "Jack" Porter

- Seat 2 – Curtis Richardson

- Seat 3 – Jeremy Matlow

- Seat 4 (Mayor) – John Dailey

- Seat 5 – Dianne Williams-Cox

- 1826 Dr. Charles Haire

- 1827 David Ochiltree

- 1828–1829 John Y. Gary

- 1830 Leslie A. Thompson

- 1831 Charles Austin

- 1832–1833 Leslie A. Thompson

- 1834 Robert J. Hackley

- 1835 William Wilson

- 1836 John Rea

- 1837 William P. Gorman

- 1838 William Hilliard

- 1839 R. F. Ker

- 1840 Leslie A. Thompson

- 1841–1844 Francis W. Eppes

- 1845 James A. Berthelot

- 1846 Simon Towle

- 1847 James Kirksey

- 1848 F. H. Flagg

- 1849 Thomas J. Perkins

- 1850–1851 D. P. Hogue

- 1852 David S. Walker

- 1853 Richard Hayward

- 1854–1855 Thomas Hayward

- 1856–1857 Francis W. Eppes

- 1858–1860 D. P. Hogue

- 1861–1865 P. T. Pearce

- 1866 Francis W. Eppes

- 1867–1868 D. P. Hogue

- 1869–1870 T. P. Tatum

- 1871 C. E. Dyke

- 1872–1874 C. H. Edwards

- 1875 David S. Walker, Jr.

- 1876 Samuel Walker

- 1877 Jesse Bernard

- 1878–1879 David S. Walker, Jr.

- 1880 Henry Bernreuter

- 1881 Edward Lewis

- 1882 John W. Nash

- 1883 Edward Lewis

- 1884–1885 Charles C. Pearce

- 1886 George W. Walker

- 1887 A. J. Fish

- 1888–1889 R. B. Forman

- 1890–1894 R. B. Carpenter

- 1895–1896 Jesse T. Bernard

- 1897 R. A. Shine

- 1898–1902 R. B. Gorman

- 1903–1904 William L. Moor

- 1905 John W. Henderson

- 1906 F. C. Gilmore

- 1907 W. M. McIntosh, Jr.

- 1908 F. C. Gilmore

- 1909 Francis B. Winthrop

- 1910–1917 D. M. Lowry

- 1918 J. R. McDaniel

- 1919–1921 Guyte P. McCord

- 1922–1923 A. P. McCaskill

- 1924–1925 B. A. Meginniss

- 1926 W. Theo Proctor

- 1927 B.A. Meginniss

- 1928–1929 W. Theo Proctor

- 1930 G. E. Lewis

- 1931 Frank D. Moor

- 1932–1933 W. L. Marshall

- 1934 J. L. Fain

- 1935 Leonard A. Wesson

- 1936 H. J. Yaeger

- 1937 L. A. Wesson

- 1938 J. R. Jinks

- 1939 S. A. Wahnish

- 1940 F. C. Moor

- 1941 Charles S. Ausley

- 1942 Jack W. Simmons

- 1943 A. R. Richardson

- 1944 Charles S. Ausley

- 1945 Ralph E. Proctor

- 1946 Fred S. Winterle

- 1947 George I. Martin

- 1948 Fred N. Lowry

- 1949–1950 Robert C. Parker

- 1951 W. H. Cates

- 1952 B. A. Ragsdale

- 1953 William T. Mayo

- 1954 H. G. Esterwood

- 1954 H. C. Summitt

- 1955–1956 J. T. Williams

- 1956 Fred S. Winterle

- 1956–1957 John Y. Humphress

- 1957 J. W. Cordell

- 1958 Davis H. Atkinson

- 1959 Hugh E. Williams, Jr.

- 1960 George S. Taft

- 1961 J. W. Cordell

- 1962 Davis H. Atkinson

- 1963 S. E. Teague, Jr.

- 1964 Hugh E. Williams, Jr.

- 1965 George S. Taft

- 1966 W. H. Cates

- 1967 John A. Rudd, Sr.

- 1968 Gene Berkowitz

- 1969 Spurgeon Camp

- 1970 Lee A. Everhart

- 1971 Gene Berkowitz

- 1972 James R. Ford

- 1973 Joan Heggen

- 1974–1975 John R. Jones

- 1976 James R. Ford

- 1977–1978 Neal D. Sapp

- 1979 Sheldon A. Hilaman

- 1980–1981 Hurley W. Rudd

- 1982 James R. Ford

- 1983 Carol Bellamy

- 1984 Kent Spriggs

- 1985 Hurley W. Rudd

- 1986 Jack McClean

- 1987–1988 Betty Harley

- 1988–1990 Dorothy Inman

- 1990 Steve Meisberg

- 1991–1992 Debbie Lightsey

- 1993–1994 Dorothy Inman-Crews

- 1994–1995 Penny Herman

- 1995–1996 Scott Maddox

- 1996–1997 Ron Weaver

- 1997–2003 Scott Maddox[50]

- 2003–2014 John Marks

- 2014–2018 Andrew Gillum

- 2018–present John Dailey

Federal representation and offices

Tallahassee is split between Florida's 2nd congressional district and Florida's 5th congressional district.

The United States Postal Service operates post offices in Tallahassee. The Tallahassee Main Post Office is at 2800 South Adams Street.[53] Other post offices in the city limits include Centerville Station,[54] Leon Station,[55] Park Avenue Station,[56] and Westside Station.[57]

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration maintains a National Weather Service in Tallahassee. Their coverage-warning area includes the eastern Florida Panhandle and adjacent Gulf of Mexico waters, the north-central Florida peninsula, and parts of southeastern Alabama and southwestern Georgia.

The United States Army Reserve 81st Regional Support Command (USAR) opened an Army Reserve Center at 4307 Jackson Bluff Road.

The Naval and Marine Corps Reserve Center (NMCRC) is at 2910 Roberts Avenue host the United States Navy Reserve Navy Operational Support Center Tallahassee (NOSC Tallahassee) and the United States Marine Corps Reserve 2nd Platoon, Company E, Anti-Terrorism Battalion and 3rd Platoon, Company E, Anti-Terrorism Battalion.

Consolidation

Voters of Leon County have gone to the polls four times to vote on consolidation of Tallahassee and Leon County governments into one jurisdiction combining police and other city services with already shared (consolidated) Tallahassee Fire Department and Leon County Emergency Medical Services. Tallahassee's city limits would increase from 103.1 square miles (267 km2) to 702 square miles (1,820 km2). Roughly 36 percent of Leon County's 265,714 residents live outside the Tallahassee city limits.

Each time, the measure was rejected:[58]

| Leon County Voting On Consolidation | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | FOR | AGAINST | |||||

| 1971 | 10,381 (41.32%) | 14,740 (58.68%) | |||||

| 1973 | 11,056 (46.23%) | 12,859 (53.77%) | |||||

| 1976 | 20,336 (45.01%) | 24,855 (54.99%) | |||||

| 1992 | 37,062 (39.8%) | 56,070 (60.2%) | |||||

The proponents of consolidation have stated the new jurisdiction would attract business by its size. Merging governments would cut government waste, duplication of services, etc. However, Professor Richard Feiock of the Department of Public Administration of Korea University and the Askew School of Public Administration and Policy of Florida State University states that no discernible relationship exists between consolidation and the local economy.[59]

Flag

The former flag of Tallahassee was vaguely similar to the flag of Florida, a white saltire on a blue field, with the city's coat of arms, featuring the cupola of the old capitol building, at the center. The flag is an homage to the Scottish and Ulster-Scots Presbyterian heritage of the original founders of the city, most of whom were settlers from North Carolina whose ancestors had either come to America directly from Scotland, or were Presbyterians of Scottish descent from County Down and County Antrim in what has since become Northern Ireland.[60] The current flag incorporates a stylized 5-point star and the city name on a white background.[61]

Education

Primary and secondary

Tallahassee anchors the Leon County School District. As of the 2009 school year Leon County Schools had an estimated 32,796 students, 2209 teachers and 2100 administrative and support personnel. The superintendent of schools is Rocky Hanna. Leon County public school enrollment continues to grow steadily (up approximately 1% per year since the 1990–91 school year). The dropout rate for grades 9–12 improved to 2.2% in the 2007–2008 school year, the third time in the past four years the dropout rate has been below 3%.

To gauge performance the State of Florida rates all public schools according to student achievement on the state-sponsored Florida Comprehensive Assessment Test (FCAT). Seventy-nine percent of Leon County Public Schools received an A or B grade in the 2008–2009 school year. The overall district grade assigned to the Leon County Schools is "A". Students in the Leon County School District continued to score favorably in comparison to Florida and national averages in the SAT and ACT student assessment tests. The Leon County School District has consistently scored at or above the average for districts statewide in total ACT and SAT mean composite scores.

- Leon County high schools

- Public schools belonging to universities

- Florida State University School ("Florida High") (K-12)

- Florida A&M University Developmental Research School (K-12)

- Charter schools

- Governor's Charter Academy (GCA) (K-8) – Established in August 2012.[62]

- School of Arts and Sciences (SAS) (K-8) – Established in 1999[63]

- Tallahassee School of Math and Science (TSMS) (K-8)[64] – It was previously known as Stars Middle School and only served middle school. In 2014 it received a new charter, adopted its current name, and expanded to elementary grades.[65]

- Private schools

- Atlantis Academy (K-12) – Established in 1976.[66]

- Community Christian School (K-12)

- John Paul II Catholic High School

- Maclay School (PK3 – 12)

- North Florida Christian High School

- Cornerstone Learning Community (PK3-8)

- Trinity Catholic School (PK3-K-8) is of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Pensacola-Tallahassee. It opened in 1952 and was then in the Roman Catholic Diocese of St. Augustine. Its initial enrollment was 102. It was moved to the Pensacola-Tallahassee diocese in 1977 upon that diocese's formation. As of 2020 its enrollment is over 450.[67]

- Holy Comforter Episcopal School (PK3 – 8)

- Woodland Hall Academy (K-12) – CLOSED

Higher education

Florida State University

Florida State University (commonly referred to as Florida State or FSU) is an American public space-grant and sea-grant research university. Florida State is on a 1,391.54-acre (5.631 km2) campus in the state capital of Tallahassee, Florida, United States. It is a senior member of the State University System of Florida. Founded in 1851, it is on the oldest continuous site of higher education in the state of Florida.[68][69]

The university is classified as a Research University with Very High Research by the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching.[70] The university comprises 16 separate colleges and more than 110 centers, facilities, labs and institutes that offer more than 360 programs of study, including professional school programs.[71] The university has an annual budget of over $1.7 billion.[72] Florida State is home to Florida's only National Laboratory – the National High Magnetic Field Laboratory and is the birthplace of the commercially viable anti-cancer drug Taxol. Florida State University also operates The John & Mable Ringling Museum of Art, the State Art Museum of Florida and one of the nation's largest museum/university complexes.[73]

The university is accredited by the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools (SACS). Florida State University is home to nationally ranked programs in many academic areas, including law, business, engineering, medicine, social policy, film, music, theater, dance, visual art, political science, psychology, social work, and the sciences.[74] Florida State University leads Florida in four of eight areas of external funding for the STEM disciplines (Science, Technology, Engineering and Math).[75]

For 2019, U.S. News & World Report ranked Florida State as the 26th best public university in the United States and 70th among top national universities.[6]

Florida Governor Rick Scott and the state legislature designated Florida State University as one of two "preeminent" state universities in the spring of 2013 among the twelve universities of the State University System of Florida.[76][77][78]

FSU's intercollegiate sports teams, commonly known by their Florida State Seminoles nickname, compete in National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) Division I and the Atlantic Coast Conference (ACC). The Florida State Seminoles athletics program are favorites of passionate students, fans and alumni across the United States, especially when led by the Marching Chiefs of the Florida State University College of Music. In their 113-year history, Florida State's varsity sports teams have won 20 national athletic championships and Seminole athletes have won 78 individual NCAA national championships.[79]

Florida A&M University

Founded on October 3, 1887, Florida A&M University (commonly referred to as FAMU) is a public, historically black university and land-grant university that is part of the State University System of Florida and is accredited by the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools. FAMU's main campus comprises 156 buildings spread over 422 acres (1.7 km2) on top of the highest geographic hill of Tallahassee. The university also has several satellite campuses, including a site in Orlando where its College of Law is located and sites in Miami, Jacksonville and Tampa for its pharmacy program. Florida A&M University offers 54 bachelor's degrees and 29 master's degrees. The university has 12 schools and colleges and one institute.

FAMU has 11 doctoral programs which include 10 PhD programs: chemical engineering, civil engineering, electrical engineering, mechanical engineering, industrial engineering, biomedical engineering, physics, pharmaceutical sciences, educational leadership, and environmental sciences. Top undergraduate programs are architecture, journalism, computer information sciences, and psychology. FAMU's top graduate programs include pharmaceutical sciences along with public health, physical therapy, engineering, physics, master's of applied social sciences (especially history and public administration), business and sociology.

Tallahassee Community College

Tallahassee Community College (TCC) is a member of the Florida College System. Tallahassee Community College is accredited by the Florida Department of Education and the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools. Its primary campus is on a 270-acre (1.092 km2) campus in Tallahassee. The institution was founded in 1966 by the Florida Legislature.[81]

TCC offers Bachelor's of Science, Associate of Arts, Associate of Science, and Associate of Applied Sciences degrees. In 2013, Tallahassee Community College was listed 1st in the nation in graduating students with A.A. degrees.[82] TCC is also the No. 1 transfer school in the nation to Florida State University and Florida A&M University. As of Fall 2015, TCC reported 38,017 students.[83]

In partnership with Florida State University, and Florida A&M University Tallahassee Community College offers the TCC2FSU, and TCC2FAMU program. This program provides guaranteed admission into Florida State University and Florida A&M University for TCC Associate in Arts degree graduates.[84][85]

List of other colleges

Economy

Companies based in Tallahassee include: Citizens Property Insurance Corporation, the Municipal Code Corporation, the State Board of Administration of Florida (SBA), the Mainline Information Systems,[86] and United Solutions Company.[87]

Top employers

According to Tallahassee's 2015 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report,[88] the top employers in the city are:

| # | Employer | # of Employees | # of Employees in 2006 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | State of Florida | 19,442 | 25,204 |

| 2 | Florida State University | 14,378 | 8,784 |

| 3 | Leon County School Board | 5,383 | 4,403 |

| 4 | Tallahassee Memorial HealthCare | 4,583 | 2,850 |

| 5 | City of Tallahassee | 2,811 | 3,327 |

| 6 | Publix | 2,200 | 2,000 |

| 7 | Tallahassee Community College | 1,518 | 1,090 |

| 8 | Florida A&M University | 1,767 | 2,681 |

| 9 | Leon County | 1,712 | 1,522 |

| 10 | Capital Regional Medical Center | 1,051 | n/a |

Arts and culture

Entertainment and performing arts

Tallahassee is home to many entertainment venues, theaters, museums, parks and performing arts centers.

A major source of entertainment and art is the Railroad Square Art Park. The Railroad Square Art Park is an arts, culture and entertainment district of Tallahassee, Florida, off Railroad Avenue, filled with a variety of metal art sculptures and stores selling artwork and collectibles. Railroad Square is mainly known for its small locally owned shops and working artist studios, and its alternative art scene. It is also known as home to the second location of Tallahassee's long-serving local business staple Black Dog Cafe. On the first Friday of every month, Railroad Square is home to a free gallery hop known as First Friday from 6pm-9pm, where a diverse group of upwards of 5000-7000+ Tallahasseeans of all ages come to meet their friends and experience art.

Museums

Tallahassee is known for its many museums. It is home to the Museum of Fine Arts at Florida State University, Tallahassee Museum, Goodward Museum & Gardens, Museum of Florida History, Mission San Luis de Apalachee, and the Tallahassee Automobile Museum.

Festivals and events

City accolades

- 1988: Money Magazine's Southeast's three top medium size cities in which to live.

- 1992: Awarded Tree City USA by National Arbor Day Foundation

- 1999: Awarded All-America City Award by the National Civic League

- 2003: Awarded Tree Line USA by the National Arbor Day Foundation.

- 2006: Awarded "Best In America" Parks and Recreation by the National Recreation and Park Association.

- 2007: Recognized by Kiplinger's Personal Finance Magazine as one of the "Top Ten College Towns for Grownups" (ranking second, behind Chapel Hill, North Carolina)

- 2007: Ranked second in the "medium sized city" class on Epodunk's list of college towns.[89]

- 2015: Awarded All-America City Award by the National Civic League[90]

Sports

Florida State Seminoles

Tallahassee is home to one of the most competitive collegiate athletics programs in the nation, the Florida State Seminoles of Florida State University. The Seminoles compete in the Atlantic Coast Conference of the National Collegiate Athletic Association. The university funds 20 varsity teams, consisting of 9 male and 11 female. They have collectively won 19 team national championships, and over 100 team conference championships, as well as numerous individual national and conference titles. The program has placed in the top-10 final standings of the Director's Cup four times since 2008–2009, including No. 4 for the 2009–2010 season and No. 4 for the 2011–2012 season. In 2016–2017, the program generated the thirteenth-most revenue in collegiate athletics with $144,514,413 of total revenue.[91]

College football game weekends bring in a significant amount of tourism to Leon County. FSU home games had a total attendance of 575,478 people with an average of 82,211 attendees per game in 2014.[92] During football season, out-of-town attendees brought $48.8 million in direct spending during the six home games. In 2016, Florida State football home games resulted in $95.5 million of economic impact on Leon County.[93]

| Teams | Division | Conference | Venue | Capacity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Florida State Seminoles football | D-1 (FBS) | ACC | Doak Campbell Stadium | 79,560 |

| Florida State Seminoles men's basketball | D-I | ACC | Donald L. Tucker Center | 12,500 |

| Florida State Seminoles women's basketball | D-I | ACC | Donald L. Tucker Center | 12,500 |

| Florida State Seminoles baseball | D-I | ACC | Dick Howser Stadium | 6,700 |

| Florida State Seminoles softball | D-I | ACC | JoAnne Graf Field | 1,000 |

| Florida State Seminoles women's soccer | D-1 | ACC | Seminole Soccer Complex | 2,000 |

| Florida A&M Rattlers | D-1 | MEAC | Bragg Memorial Stadium | 25,500 |

| Florida A&M Rattlers men's basketball | D-I | MEAC | Teaching Arena | 8,470 |

Other

| Club | Sport | League | Years Active | Venue |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tallahassee Tiger Sharks | Hockey | ECHL | 1994–2001 | Donald L. Tucker Center |

| Tallahassee Scorpions | Indoor soccer | EISL | 1997–1998 | Donald L. Tucker Center |

| Tallahassee Thunder | American Football | Arena Football | 2000–2002 | Donald L. Tucker Center |

| Tallahassee Titans | American Football | AIFL | 2006 | Donald L. Tucker Center |

| Tallahassee Tigers | Basketball | ABA | 2007 | Donald L. Tucker Center |

| Tallahassee SC | Soccer | NPSL | 2018– | Gene Cox Stadium |

Tallahassee is home to Tallahassee SC, a soccer club that was founded in 2018 and plays in the National Premier Soccer League.

Some former sports clubs in Tallahassee include the Tallahassee Tiger Sharks, Tallahassee Scorpions, Tallahassee Thunder, Tallahassee Titans, and the Tallahassee Tigers.

Media

Print

- The Tallahassee Democrat, Tallahassee's largest newspaper, published daily[94]

- The FSView & Florida Flambeau, covers Florida State University[95]

- The Talon, covers Tallahassee Community College[96]

- The Famuan, covers Florida A&M University[97]

Television

- WCTV (CBS) channel 6.1 (MeTV) channel 6.2 (Circle) channel 6.3 (ION) channel 6.4 (Justice) channel 6.5 (MyTV) channel 6.6

- WFSU (PBS) channel 11.1 (Florida Channel) channel 11.2 (Create) channel 11.3 (Kids 360) channel 11.4

- WTLF (CW) channel 24.1 (Comet) channel 24.2 (TBD) 24.3 (Stadium) 24.4 (Dabl) channel 24.5

- WTLH (H&I) channel 49.1 (CW) channel 49.2 (Comet) 49.3

- WTWC (NBC) channel 40.1 (Fox) channel 40.2 (Charge) channel 40.3

- WTXL (ABC) channel 27.1 (Bounce) channel 27.2 (Grit) channel 27.3 (Escape) channel 27.4 (CourtTV) channel 27.5

- WNXG-LD (WCTVDT2/MeTV) channel 38.1 (Start TV) channel 38.2 (Decades) channel 38.3[98]

- WVUP (CTN) channel 45.1 (LifeStyle) channel 45.2

Radio

- WANM, Soul/R&B music

- WAYT-FM, contemporary Christian music

- WBZE-FM, adult contemporary music

- WDXD-LP, classic country music

- WFLA-FM, news/talk

- WFSQ-FM, classical music

- WFSU-FM, news/talk

- WGLF-FM, classic rock music

- WGMY-FM, Top 40 music

- WHTF-FM, Top 40 music

- WTLY, adult contemporary music

- WTNT-FM, country music

- WVFS-FM, college/alternative music

- WVFT, news/talk

- WWLD, hip-hop music

- WWOF-FM, country music

- WXSR-FM, rock music

Public safety

Established in 1826, the Tallahassee Police Department once claimed to be the oldest police department in the Southern United States, and the second-oldest in the U.S., preceded only by the Philadelphia Police Department (established in 1758). The Boston Police Department was established in 1838 and larger East Coast cities followed with New York City and Baltimore in 1845. However, this is proven incorrect. Pensacola, Florida, for example, had a municipal police force as early as 1821.[99]

There are over 800 sworn law enforcement officers in Tallahassee. Law enforcement services are provided by the Tallahassee Police Department, the Leon County Sheriff's Office, the Florida Department of Law Enforcement, Florida Capitol Police, Florida State University Police Department, Florida A&M University Police Department, the Tallahassee Community College Police Department, the Florida Highway Patrol, and the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission.

The Tallahassee Growth Management Building Inspection Division is responsible for issuing permits and performing inspections of public and private buildings in the city limits. These duties include the enforcement of the Florida Building Codes and the Florida Fire Protection Codes. These standards are present to protect life and property. The Tallahassee Building Department is one of 13 Accredited Building Departments in the United States.[100]

The Federal Bureau of Investigation, United States Marshals Service, Immigration and Customs Enforcement,[101] Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives, Secret Service and Drug Enforcement Administration have offices in Tallahassee. The United States District Court for the Northern District of Florida is based in Tallahassee.

Fire and rescue services are provided by the Tallahassee Fire Department and Leon County Emergency Medical Services.

Hospitals in the area include Tallahassee Memorial Healthcare, Capital Regional Medical Center and HealthSouth Rehabilitation Hospital of Tallahassee.

Places of interest

- Alfred B. Maclay Gardens State Park

- Carnegie Library at FAMU

- Challenger Learning Center

- Co-Cathedral of St. Thomas More

- College Town at Florida State University

- Doak Campbell Stadium

- Elinor Klapp-Phipps Park

- First Presbyterian Church

- Florida Governor's Mansion

- Florida State Capitol

- Florida Supreme Court

- Foster Tanner Fine Arts Gallery at Florida A&M University

- Goodwood Museum and Gardens

- Innovation Park

- John G. Riley Center/Museum of African American History & Culture (Riley Museum)

- Knott House Museum

- Lake Ella

- Lake Jackson Mounds Archaeological State Park

- Lafayette Heritage Trail Park

- LeMoyne Center for the Visual Arts

- Mission San Luis de Apalachee

- Museum of Fine Arts at Florida State University

- Museum of Florida History

- National High Magnetic Field Laboratory

- North Florida Fairgrounds

- Railroad Square

- Southeastern Regional Black Archives Research Center and Museum

- St. John's Episcopal Church

- Tallahassee Automobile Museum

- Tallahassee Museum

- James D. Westcott Building and Ruby Diamond Auditorium at Florida State University

Transportation

Aviation

Defunct airports

- Dale Mabry Field (closed 1961)

- Tallahassee Commercial Airport (closed 2011)

Mass transit

- StarMetro provides bus service throughout the city.

Railroads

- Freight service is provided by the Florida Gulf & Atlantic Railroad, which acquired most of the CSX main line from Pensacola to Jacksonville on June 1, 2019. FG&A also purchased the CSX branch from Tallahassee to Attapulgus, Georgia, connecting with the CSX Montgomery-Savannah main line at Bainbridge, Georgia. FG&A's headquarters office is in Tallahassee.[102]

Defunct railroads and passenger trains

- Tallahassee Railroad, completed in 1837, now the state-owned Tallahassee-St. Marks Historic Railroad State Trail from Tallahassee southward to St. Marks, about 20 miles.

- Carrabelle, Tallahassee and Georgia Railroad, founded in 1891, merged into the Georgia Florida and Alabama Railway in 1906. The Tallahassee-Carrabelle segment was abandoned in 1948.[103] In 2009, a 2.4-mile segment of the abandoned railroad was opened as the Tallahassee-Georgia Florida and Alabama (GF&A) Trail in the Apalachicola National Forest.[104]

- The streamlined Gulf Wind coach and Pullman passenger train, operated jointly by the L&N and Seaboard railroads, served Tallahassee from 1949 to 1971.

- Amtrak's Sunset Limited was suspended in 2005, following Hurricane Katrina, which caused extensive damage to CSX lines from Louisiana to Florida. The service has never been reinstated, and as of mid-2019 had a "next to zero chance" of being revived by Amtrak.[105] The Tallahassee and Pensacola metropolitan areas are the largest in the state without passenger rail service.

Major highways

Interstate 10 runs east and west across the north side of the city. Tallahassee is served by five exits including: Exit 192 (U.S. 90), Exit 196 (Capital Circle NW), Exit 199 (U.S. 27/Monroe St.), Exit 203 (U.S. 319/Thomasville Road and Capital Circle NE), and Exit 209 (U.S. 90/Mahan Dr.)

Interstate 10 runs east and west across the north side of the city. Tallahassee is served by five exits including: Exit 192 (U.S. 90), Exit 196 (Capital Circle NW), Exit 199 (U.S. 27/Monroe St.), Exit 203 (U.S. 319/Thomasville Road and Capital Circle NE), and Exit 209 (U.S. 90/Mahan Dr.) U.S. Route 27 enters the city from the northwest before turning south and entering downtown. This portion of U.S. 27 is known locally as Monroe Street. In front of the historic state capitol building, U.S. 27 turns east and follows Apalachee Parkway out of the city.

U.S. Route 27 enters the city from the northwest before turning south and entering downtown. This portion of U.S. 27 is known locally as Monroe Street. In front of the historic state capitol building, U.S. 27 turns east and follows Apalachee Parkway out of the city. U.S. Route 90 runs east and west through Tallahassee. It is known locally as Tennessee Street west of Magnolia Drive and Mahan Drive east of Magnolia.

U.S. Route 90 runs east and west through Tallahassee. It is known locally as Tennessee Street west of Magnolia Drive and Mahan Drive east of Magnolia. U.S. Route 319 runs north and south along the east side of the city using Thomasville Road, Capital Circle NE, Capital Circle SE, and Crawfordville Road.

U.S. Route 319 runs north and south along the east side of the city using Thomasville Road, Capital Circle NE, Capital Circle SE, and Crawfordville Road. State Road 20

State Road 20 State Road 61

State Road 61 State Road 363

State Road 363- Orchard Pond Parkway, the first privately-built toll road in Florida.[106]

Tallahassee groups and organizations

- Cold Water Army, music group

- Creed, rock band

- Cream Abdul Babar, music group

- The Crüxshadows, music group

- David Canter, medical doctor, folk musician

- Dead Prez, Alternative hip hop duo

- Go Radio, music group

- FAMU Marching 100, marching band

- FSU Marching Chiefs, marching band

- Look Mexico, rock band

- Mayday Parade, music group

- Mira, music group

- No Address, music group

- Socialburn, rock band

- Tallahassee Symphony Orchestra, symphony orchestra

- Woman's Club of Tallahassee

Namesakes

- CSS Tallahassee, 1864 Confederate cruiser

- USS Tallahassee (BM-9), 1908 United States Navy monitor, originally named USS Florida

- USS Tallahassee (CL-61), 1941 United States Navy light cruiser, converted to the aircraft carrier USS Princeton

- USS Tallahassee (CL-116), 1944 United States Navy light cruiser

- Tallahassee, main character in the movie Zombieland

- Tallahassee, album recorded by The Mountain Goats

- Tallahassee Community School, Eastern Passage, Nova Scotia, named after CSS Tallahassee[107]

- Tallahassee Tight, early-20th century blues singer

- T-Pain, musician, originally "Tallahassee Pain"

- "Tallahassee Lassie", Freddy Cannon song

Sister cities

Tallahassee has 6 sister cities as follows:

Konongo-Odumase, Ashanti, Ghana

Konongo-Odumase, Ashanti, Ghana Krasnodar, Krasnodar Krai, Russia

Krasnodar, Krasnodar Krai, Russia St. Maarten, Netherlands Antilles

St. Maarten, Netherlands Antilles Sligo, County Sligo, Ireland

Sligo, County Sligo, Ireland Rugao, Jiangsu, China

Rugao, Jiangsu, China Ramat HaSharon, Tel Aviv District, Israel

Ramat HaSharon, Tel Aviv District, Israel

Gallery

Turlington Education Building as seen from the Civic Center

Turlington Education Building as seen from the Civic Center The Downtown Tallahassee Doubletree Hotel

The Downtown Tallahassee Doubletree Hotel Tennyson Condominiums as seen through a break in the downtown Federal Courthouse Square

Tennyson Condominiums as seen through a break in the downtown Federal Courthouse Square Westminster Gardens, formerly the Georgia Bell Dickinson Apartments, in Downtown Tallahassee

Westminster Gardens, formerly the Georgia Bell Dickinson Apartments, in Downtown Tallahassee Highpoint Center as seen from the Florida Capitol

Highpoint Center as seen from the Florida Capitol The historic Exchange Bank Building, considered to be the city's first highrise building

The historic Exchange Bank Building, considered to be the city's first highrise building The Korean War Memorial at Cascades Park facing the Florida Capitol

The Korean War Memorial at Cascades Park facing the Florida Capitol Union Bank, Florida's oldest surviving bank building

Union Bank, Florida's oldest surviving bank building Florida's historic state capitol building built in 1845

Florida's historic state capitol building built in 1845 Kleman Plaza in the heart of Downtown Tallahassee

Kleman Plaza in the heart of Downtown Tallahassee The U.S. Federal Courthouse in Tallahassee

The U.S. Federal Courthouse in Tallahassee%252C_Korean_War_Memorial_02.JPG.webp) The Florida Korean War Memorial

The Florida Korean War Memorial The Florida Supreme Court Building

The Florida Supreme Court Building The Tallahassee-Leon County Visitors Center

The Tallahassee-Leon County Visitors Center

Notable people

This is a list of notable people from Tallahassee, in alphabetical order by last name:

- Cannonball Adderley, musician

- Wally Amos (born 1936), television personality and founder of Famous Amos Cookies[108]

- Bobby Bowden, Florida State University football coach

- LeRoy Collins, Florida governor

- Paul Dirac, theoretical physicist and Nobel Laureate

- Julian Green, soccer player

- Robert A. Holton, chemist and inventor of Taxol

- Kent Jones, musician

- Sir Harold Kroto, Nobel Prize-winning scientist

- Payne Midyette (1898–1983), insurance broker, Tallahassee politician and rancher[109]

- Jim Morrison, musician

- W. Stanley "Sandy" Proctor, sculptor[110]

- T-Pain, rapper turned singer

- Yvonne Edwards Tucker (born 1941), potter

- Ann VanderMeer, Hugo Award-winning Editor[111]

- Jeff VanderMeer, New York Times Bestselling Author[112]

- Florence Duval West (1840–1881), poet

State associations based in Tallahassee

See also

References

- "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 2, 2020.

- "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. October 25, 2007. Archived from the original on February 26, 2012. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". Retrieved May 21, 2020.

- "Table 1: 2010 Municipality Population" (CSV). 2010 Population. United States Census Bureau, Population Division. March 24, 2010. Archived from the original on January 3, 2010. Retrieved July 1, 2009.

- "rankings". www.usnews.com. Archived from the original on September 10, 2018. Retrieved September 9, 2019.

- "How Does FAMU Rank Among America's Best Colleges?". Colleges.usnews.rankingsandreviews.com. Archived from the original on January 20, 2015. Retrieved November 22, 2017.

- "Team, News, Projects | Tallahassee Investor Relations | BondLink". www.tallahasseebonds.com. Retrieved June 15, 2020.

- "Florida Chamber of Commerce | Home Page". Flchamber.com. Archived from the original on August 4, 2014. Retrieved August 2, 2014.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on July 12, 2014. Retrieved August 2, 2014.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "North America's first Christmas? – Tallahassee Magazine – November–December 2012". www.tallahasseemagazine.com. Archived from the original on December 1, 2017. Retrieved November 30, 2017.

- "Name Origins of Florida Places". Florida Department of State, Division of Historical Resources. Archived from the original on July 29, 2014. Retrieved July 7, 2014.

- Hare, p.22

- Florida: A Short History, Michael V. Gannon, ISBN 0-8130-1167-1, 1993

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on June 20, 2004. Retrieved May 10, 2006.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Slavery and Plantation Growth in Antebellum, Florida, 1821–1860". Questia.com. July 30, 2012. Archived from the original on August 12, 2011. Retrieved August 2, 2014.

- "History". Office of University Communications, Florida State University. Archived from the original on January 7, 2018. Retrieved December 21, 2010.

- "Race and Hispanic Origin for Selected Cities and Other Places: Earliest Census to 1990". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on August 12, 2012.

- "Florida Historic Capitol Museum". Flhistoriccapitol.gov. Archived from the original on June 29, 2014. Retrieved August 2, 2014.

- Ensley, Gerald (September 26, 2015). "1982 election last gasp of 'good 'ol boy' system". Tallahassee Democrat.

- "Hurricane Hermine: By the numbers". Tallahassee Democrat. Archived from the original on February 23, 2019. Retrieved February 22, 2019.

- "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. February 12, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- "Tallahassee | Buildings | EMPORIS". Archived from the original on August 10, 2019. Retrieved August 10, 2019.

- "Land Use Element of the Tallahassee-Leon County Comprehensive Plan" (PDF). Talgov.com. January 22, 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 14, 2017. Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- Hamidi, Shima; Ewing, Reid (August 1, 2014). "A longitudinal study of changes in urban sprawl between 2000 and 2010 in the United States". Landscape and Urban Planning. 128: 72–82. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2014.04.021.

- "The U.S. Cities That Sprawled the Most (and Least) Between 2000 and 2010". CityLab. Archived from the original on January 18, 2017. Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- "NowData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved February 25, 2012.

- "NOAA Weather Records Tallahassee". NOAA. Archived from the original on September 29, 2006. Retrieved June 15, 2011.

- "USDA Plant Hardiness Zone Map". United States Department of Agriculture. Archived from the original on February 27, 2014. Retrieved March 22, 2018.

- Etters, Karl (February 7, 2016). "Chance of flurries dim, despite a cold week". Tallahassee Democrat. February 7, 2016. p. A3.

- "Pattern Recognition of Significant Snowfall Events in Tallahassee, Florida" (PDF). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, National Weather Service. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 16, 2013. Retrieved March 1, 2013.

- Truchelut, Ryan (January 3, 2018). "Tallahassee saw an hour of snow for the history books Archived December 26, 2018, at the Wayback Machine". Tallahassee Democrat.

- "Confirmed Tornado Touched Down in Leon County Sunday". WCTV-TV. Archived from the original on June 20, 2017. Retrieved November 22, 2017.

- CNN, Dave Hennen and Holly Yan. "A tornado strikes Florida's capital, damaging Tallahassee International Airport". CNN. Retrieved January 27, 2021.

- Mean monthly maxima and minima (i.e. the highest and lowest temperature readings during an entire month or year) calculated based on data at said location from 1981 to 2010.

- "Station Name: FL TALLAHASSEE". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved March 22, 2018.

- "Tallahassee, Florida, USA – Monthly weather forecast and Climate data". Weather Atlas. Archived from the original on November 5, 2018. Retrieved September 18, 2018.

- United States Census Bureau. "Census of Population and Housing". Retrieved April 29, 2015.

- "State and County QuickFacts Tallahassee (city), Florida". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on July 15, 2012. Retrieved December 9, 2015.

- https://statisticalatlas.com/state/Florida/Educational-Attainment

- https://statisticalatlas.com/county/Florida/Leon-County/Educational-Attainment

- "Highest Educational Levels Reached by Adults in the U.S. Since 1940".

- "Modern Language Association Data Center Results of Tallahassee, Florida". Mla.org. April 2, 2013. Archived from the original on June 29, 2014. Retrieved August 2, 2014.

- Eisenberg, Daniel (1986). "In Tallahassee" (PDF). Journal of Hispanic Philology. 10 (2). pp. 97–101. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 6, 2014.

- "U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: Tallahassee city, Florida; UNITED STATES". www.census.gov. Archived from the original on May 11, 2019. Retrieved May 11, 2019.

- "Just How Liberal Are College Students? – Harvard Political Review". April 25, 2014. Archived from the original on May 11, 2019. Retrieved May 11, 2019.

- "Home – Leon County Supervisor of Elections". www.leonvotes.org. Archived from the original on December 3, 2018. Retrieved December 3, 2018.

- "Leon Supervisor of Elections Office". Leoncountyfl.gov. Archived from the original on August 10, 2014. Retrieved August 2, 2014.

- "Tallahassee City Leadership". www.talgov.com. Retrieved November 9, 2020.

- "City Officials". City of Tallahassee. Archived from the original on June 5, 1997 – via Internet Archive, Wayback Machine.

- Hubbard, Linda S. (1988). Notable Americans: What They Did, from 1620 to the Present. Gale. p. 387.

- "Tallahassee Mayors Intendants". Stumper. Leon County, Florida. Archived from the original on October 13, 2017. Retrieved October 12, 2017.

- "Post Office Location – TALLAHASSEE." United States Postal Service. Retrieved on May 6, 2009.

- "Post Office Location – CENTERVILLE STATION." United States Postal Service. Retrieved on May 6, 2009.

- "Post Office Location – LEON STATION." United States Postal Service. Retrieved on May 6, 2009.

- "Post Office Location – PARK AVENUE STATION." United States Postal Service. Retrieved on May 6, 2009.

- "Post Office Location – WESTSIDE STATION." United States Postal Service. Retrieved on May 6, 2009.

- "Consolidation of City (Tallahassee) & County (Leon) Government" (PDF). Leon County Supervisor of Elections. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 7, 2017. Retrieved November 2, 2017.

- "City County Consolidation Efforts: Selective Incentives and Institutional Choice" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on June 14, 2007. Retrieved August 2, 2014.

- Purcell, John M. (2004). American City Flags (Part I: United States): 150 Flags from Akron to Yonkers. Trenton, New Jersey: North American Vexillological Association. p. 345. ISBN 978-0-9747728-0-6. Retrieved February 11, 2011.

- "Calmet: Design a new flag for Tallahassee". Tallahassee.com. Archived from the original on September 3, 2017. Retrieved November 22, 2017.

- "About Us". Governor's Charter Academy. Retrieved May 20, 2020.

- "About SAS". School of Arts and Sciences. Retrieved May 20, 2020.

- "Contact Us". Tallahassee School of Math and Science. Retrieved May 20, 2020.

- Hatter, Lynn (December 9, 2014). "Stars Middle School Gets New Name, New Grades Levels And New Charter". WFSU. Retrieved May 20, 2020.

- "History". Atlantis Academy. Retrieved May 20, 2020.

- "History". Trinity Catholic School. Retrieved May 20, 2020.

- Meginniss, Benjamin A.; Winthrop, Francis B.; Ames, Henrietta O.; Belcher, Burton E.; Paret, Blanche; Holliday, Roderick M.; Crawford, William B.; Belcher, Irving J. (1902). "The Argo of the Florida State College". The Franklin Printing & Publishing Co., Atlanta. Archived from the original on January 18, 2016. Retrieved April 26, 2013.

- Klein, Barry (July 29, 2000). "FSU's age change: history or one-upmanship?". St. Petersburg Times. Archived from the original on October 17, 2012. Retrieved July 9, 2010.

- "Florida State University". Classifications. The Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching. 2013. Archived from the original on June 29, 2018. Retrieved April 26, 2013.

- "Colleges, Schools, Departments, Institutes, and Administrative Units". FSU Departments. Florida State University. April 26, 2013. Archived from the original on April 30, 2013. Retrieved April 26, 2013.

- "Florida State University Board of Trustees Meeting". Learningforlife.capd.fsu.edu. Archived from the original on October 13, 2015. Retrieved November 22, 2017.

- "The John & Mable Ringling Museum of Art". FSU Departments. The John & Mable Ringling Museum of Art. April 26, 2013. Archived from the original on May 17, 2013. Retrieved April 26, 2013.

- "Florida State University – College Highlights and Selected National Rankings". Archived from the original on May 16, 2007. Retrieved May 1, 2007.

- "FSU Highlights". fsu.edu. Archived from the original on October 17, 2015. Retrieved October 18, 2015.

- James Call (June 10, 2013). "UF, FSU get special designation, more money". The Florida Current. Archived from the original on November 3, 2013. Retrieved June 12, 2013.

- "CS/CS/SB 1076: K-20 Education". Flsenate.gov. Archived from the original on April 20, 2013. Retrieved April 23, 2013.

- "Our Opinion: FSU benefits from pre-eminent status". The Tallahassee Democrat. Archived from the original on October 30, 2014. Retrieved April 23, 2013.

- Joanos, Jim (June 2012). "FSU Athletics Timeline". Archived from the original on July 3, 2013. Retrieved April 26, 2013.

- "Lee Hall Auditorium : Florida Agricultural and Mechanical University 2017". Famu.edu. Archived from the original on December 1, 2017. Retrieved November 22, 2017.

- "404 – Tallahassee Community College". www.tcc.fl.edu. Archived from the original on February 8, 2012.

- "Associate Degree & Certificate Producers, 2013". Ccweek.com. Archived from the original on May 17, 2017. Retrieved November 22, 2017.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 5, 2017. Retrieved April 5, 2017.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Library – Tallahassee Community College". Tcc.fl.edu. Archived from the original on April 3, 2016. Retrieved November 22, 2017.

- "TCC2FAMU – Tallahassee Community College". www.tcc.fl.edu. Archived from the original on May 8, 2019. Retrieved May 11, 2019.

- "Mainline – IT Solutions, Software, Managed Business Services". Mainline. Archived from the original on October 17, 2017. Retrieved November 22, 2017.

- "Core Processing for Credit Unions". Unitedsolutions.coop. Archived from the original on September 30, 2017. Retrieved November 22, 2017.

- "City of Tallahassee CAFR" (PDF). Talgov.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 11, 2017. Retrieved April 21, 2017.

- "ePodunk College Towns Index". Epodunk.com. Archived from the original on June 29, 2014. Retrieved August 2, 2014.

- Ensley, Gerald. "Tallahassee named All-America City — again". Tallahassee Democrat. Archived from the original on November 20, 2018. Retrieved July 24, 2016.

- "USA TODAY Sports". USA TODAY Sports. Archived from the original on September 28, 2018. Retrieved May 5, 2019.

- "Football attendance records" (PDF). fs.ncaa.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 15, 2015. Retrieved May 15, 2019.

- "Home". Florida State's Economic Impact. Archived from the original on December 3, 2018. Retrieved December 3, 2018.

- "Tallahassee Democrat | Tallahassee news, community, entertainment, yellow pages and classifieds. Serving Tallahassee, Florida". Tallahassee.com. October 12, 2012. Archived from the original on October 14, 2012. Retrieved October 16, 2012.

- "Florida State University news from the FSView and Florida Flambeau including FSU sports, arts and life, opinion and classifieds. | fsunews.com". FSView.com. October 12, 2012. Archived from the original on March 29, 2004. Retrieved October 16, 2012.

- "The Talon Newspaper – Tallahassee Community College". Tcc.fl.edu. Archived from the original on September 7, 2015. Retrieved November 22, 2017.

- "The Famuan – The Student Voice of Florida A&M University". Thefamuanonline.com. Archived from the original on October 14, 2012. Retrieved October 16, 2012.

- "WNXG-LD TALLAHASSEE, FL". www.rabbitears.info. Retrieved December 6, 2020.

- Domherty, Jr., Herbert J. (1954). "The Governorship of Andrew Jackson". The Florida Historical Quarterly. 33 (1): 3–31. JSTOR 30138932.

- "Building Department Accreditation". International Accreditation Service. Archived from the original on May 19, 2011. Retrieved May 24, 2011.

- "Florida Gulf & Atlantic Railroad". RailUSA. Archived from the original on June 19, 2019. Retrieved October 19, 2019.

- Hensley, Jr., Donald R. "The Story of the Georgia Florida & Alabama RR". Tap Lines. Archived from the original on April 4, 2019. Retrieved October 19, 2019.