Ludovico Sforza

Ludovico Maria Sforza (Italian pronunciation: [ludoˈviːko maˈriːa ˈsfɔrtsa]; 27 July 1452 – 27 May 1508), also known as Ludovico il Moro (Italian: [il ˈmɔːro]; "the Moor"),[lower-alpha 2] was an Italian Renaissance prince who ruled as Duke of Milan from 1494, following the death of his nephew Gian Galeazzo Sforza, until 1499. A member of the Sforza family, he was the fourth son of Francesco I Sforza. He was famed as a patron of Leonardo da Vinci and other artists, and presided over the final and most productive stage of the Milanese Renaissance. He is probably best known as the man who commissioned The Last Supper, as well as for his role in precipitating the Italian Wars.

| Ludovico Sforza | |

|---|---|

Ludovico's portrait in the Pala Sforzesca, 1494–1495 (Pinacoteca di Brera in Milan)[lower-alpha 1] | |

| Duke of Milan | |

| Reign | 21 October 1494 – 6 September 1499 |

| Predecessor | Gian Galeazzo Sforza |

| Successor | Louis XII of France |

| Regent of Milan | |

| Regency | 7 October 1480 – 21 October 1494 |

| Monarch | Gian Galeazzo Sforza |

| Born | 27 July 1452 Vigevano, Duchy of Milan (modern day Lombardy, Italy) |

| Died | 27 May 1508 (aged 55) Château de Loches (died as a prisoner of the French) |

| Spouse | Beatrice d'Este |

| Issue |

|

| House | Sforza |

| Father | Francesco I Sforza |

| Mother | Bianca Maria Visconti |

Early life

Ludovico Sforza was born on 27 July 1452 at Vigevano, in what is now Lombardy. He was the fourth son of Francesco I Sforza and Bianca Maria Visconti[3] and, as such, was not expected to become ruler of Milan. Nevertheless, his mother, Bianca, prudently saw to it that his education was not restricted to the classical languages. Under the tutelage of the humanist Francesco Filelfo, Ludovico received instruction in the beauties of painting, sculpture, and letters, but he was also taught the methods of government and warfare.

Regent of Milan

.jpg.webp)

When their father Francesco died in 1466, the family titles devolved upon the dissolute Galeazzo Maria, the elder brother, whilst Ludovico was conferred the courtesy title of Count of Mortara.[4]

Galeazzo Maria ruled until his assassination in 1476, leaving his titles to his seven-year-old son, Gian Galeazzo Sforza, Ludovico's nephew. A bitter struggle for the regency with the boy's mother, Bona of Savoy, ensued; Ludovico emerged as victor in 1481 and seized control of the government of Milan, despite attempts to keep him out of power. For the following 13 years he ruled Milan as its Regent, having previously been created Duke of Bari in 1479.[5]

Marriage and private life

In January 1491, he married Beatrice d'Este (1475-1497) the youngest daughter of Ercole d'Este Duke of Ferrara,[5] in a double Sforza-Este marriage, while Beatrice's brother, Alfonso I d'Este, Duke of Ferrara, married Anna Sforza, Ludovico's niece. Leonardo da Vinci orchestrated the wedding celebration. Beatrice and Alfonso's sister, Isabella d'Este (1474–1539) was married to Francesco II Gonzaga, Marquess of Mantua.

The 15-year-old princess quickly charmed the Milanese court with her joy in life, her laughter, and even her extravagance. She helped to make Sforza Castle a center of sumptuous festivals and balls and she loved entertaining philosophers, poets, diplomats and soldiers. Beatrice had good taste, and it is said that under her prompting her husband's patronage of artists became more selective and the likes of Leonardo da Vinci and Donato Bramante were employed at the court.[5] She would become the mother of Maximilian Sforza and Francesco II Sforza, future Dukes of Milan.

Prior to and throughout the duration of his 6-year marriage, Ludovico is known to have had mistresses, although it is thought that he kept only one mistress at a time. Bernardina de Corradis was an early mistress who bore him a daughter, Bianca Giovanna (1483–1496), supposedly the sitter for the disputed work La Bella Principessa. The child was legitimized and later married to Galeazzo da Sanseverino in 1496. Cecilia Gallerani, believed to be a favourite, gave birth to a son named Cesare on 3 May 1491, in the same year in which Ludovico married Beatrice d'Este. Gallerani is identified as the subject of Leonardo da Vinci's Lady with an Ermine – the ermine was the heraldic animal of Ludovico il Moro. Another mistress was Lucrezia Crivelli, who bore him another illegitimate son, Giovanni Paolo, born in the year of Beatrice's death. He was a condottiero. Ludovico also fathered a third illegitimate son, called Sforza, who was born around 1484 and died suddenly in 1487; the boy's mother is unknown.[6]

Rule as regent

Ludovico invested in agriculture, horse and cattle breeding, and the metal industry. Some 20,000 workers were employed in the silk industry. He sponsored extensive work in civil and military engineering, such as canals and fortifications, continued work on the Cathedral of Milan and had the streets of Milan enlarged and adorned with gardens. The university of Pavia flourished under him. There were some protests at the heavy taxation necessary to support these ventures, and a few riots resulted.

Ascension as Duke of Milan and the Italian Wars

In 1494, the new king of Naples, Alfonso II, allied himself with Pope Alexander VI, posing a threat to Milan. Ludovico decided to fend him off using France, then ruled by Charles VIII, as his ally. He permitted the French troops to pass through Milan so they might attack Naples. However, Charles's ambition was not satisfied with Naples, and he subsequently laid claim to Milan itself. Bitterly regretting his decision, Ludovico then entered an alliance with Emperor Maximilian I, by offering him in marriage his niece Bianca Sforza and receiving, in return, imperial investiture of the duchy and joining the league against France.

Gian Galeazzo, his nephew,[7] died under suspicious conditions in 1494, and the throne of Milan fell to Ludovico, who hastened to assume the ducal title and received the ducal crown from the Milanese nobles on 22 October. But by then, his luck seemed to have run out. On 3 January 1497, as the result of a difficult childbirth, Beatrice, his wife, died. Ludovico was inconsolable, and the entire court was shrouded in gloom. Ludovico had also hoped by involving the French, and Maximilian I, in Italian politics, he could manipulate the two and reap the rewards himself, and was thus responsible for starting the Italian Wars. At first, Ludovico defeated the French at the Battle of Fornovo in 1495 (making weapons from 80 tons of bronze originally intended for the colossal equestrian statue commissioned by the duke from Leonardo da Vinci in honour of Francesco I Sforza). However, with the death of Charles, the French throne was inherited by his cousin, Louis of Orléans, who became Louis XII of France. The new king had a hereditary claim to Milan, as his paternal grandmother was Valentina Visconti, daughter of Giangaleazzo Visconti, the first Duke of Milan. Hence in 1498, he descended upon Milan. As none of the other Italian states would help the ruler who had invited the French into Italy four years earlier, Louis was successful in driving out Ludovico from Milan. Ludovico managed to escape the French armies and, in 1499, sought help from Maximilian.

Downfall and aftermath

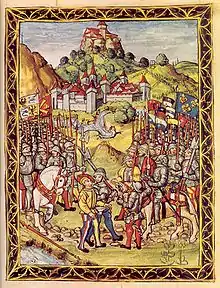

Ludovico returned with an army of mercenaries and re-entered Milan in February 1500. Two months later, Louis XII laid siege to the city of Novara, where Ludovico was based. The armies of both sides included Swiss mercenaries. The Swiss did not want to fight each other and chose to leave Novara. Ludovico was handed over to the French in April 1500 in the so-called Treason of Novara (Verrat von Novara). This incident took place in 1500 in the context of the involvement of the Old Swiss Confederacy in the Italian Wars, and is mentioned briefly in Chapter 3 of Niccolò Machiavelli's The Prince.

About 6,000 Swiss under the command of Sforza defended the city, while about 10,000 Swiss under the command of Louis laid siege to it. The Swiss diet called for negotiations between the two sides in an attempt to prevent the worst case of the Swiss on both sides being forced to slaughter one another, "brothers against brothers and fathers against sons". Louis agreed to a conditional surrender which would grant free passage to the Swiss abandoning the city, but only under the condition that Sforza would be surrendered. However, the Swiss on Sforza's side, under an oath of loyalty to their employer, decided to dress Sforza as a Swiss and smuggle him out of town.

On 10 April, the Swiss garrison was leaving Novara, passing a cordon formed by the Swiss on the French side. French officers were posted to oversee their exit. As the disguised Sforza passed the cordon, one mercenary Hans (or Rudi) Turmann of Uri made signs giving away Sforza's identity. The duke was apprehended by the French. Louis XII refused to see him and, despite the pleas of the Emperor Maximilian, would not release him. However, he did allow him to roam the grounds of the castle of Lys-Saint-Georges in Berry where he was held, to fish in the moat and to receive friends. When he fell ill, Louis sent him his own physician as well as one of Ludovico's dwarf entertainers to amuse him. In 1504 he was moved to the castle of Loches where he was given even more freedom. In 1508, Ludovico attempted to escape; he was thereafter deprived of amenities including his books and spent the rest of his life in the castle's dungeon, where he died on 27 May 1508.[8] The French rewarded Turmann for his treason with 200 gold crowns (corresponding to five years' salary of a mercenary); he escaped to France, but after three years (or, according to some sources, after one year) he returned home to Uri. Turmann was immediately arrested for treason, and on the following day he was executed by decapitation.[9]

The Swiss later restored the Duchy of Milan to Ludovico's son, Maximilian Sforza. His other son, Francesco II, also held the duchy for a short period. Francesco II died in 1535, sparking the Italian War of 1536–1538, as a result of which Milan passed to the Spanish Empire.

The memory of Ludovico was clouded for centuries by Machiavelli's accusation that he 'invited' Charles VIII to invade Italy, paving the way for subsequent foreign domination. The charge was perpetuated by later historians who espoused the ideal of national independence. More recent historians, however, placing the figure of Ludovico in its Renaissance setting, have reevaluated his merits as a ruler and given a more equitable assessment of his achievement.[10]

Representations in popular culture

- In the 1971 RAI miniseries La Vita di Leonardo Da Vinci, Ludovico Sforza is portrayed by Italian actor Giampiero Albertini.

- In the 2011 Showtime series The Borgias, Ludovico Sforza is portrayed by English actor Ivan Kaye.

- In the 2011 Canal+ series Borgia, Ludovico Sforza is portrayed by Austrian actor Manuel Rubey.

Ancestors

| Ancestors of Ludovico Sforza | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notes

- This depiction is one of the most famous portraits of Ludovico. The altarpiece with which is originates is by an unknown artist, thought to from be the circle of Leonardo da Vinci.[1]

- Il Moro literally means "The Moor", an epithet said by Francesco Guicciardini to have been given to Ludovico because of his dark complexion. In modern Italian, moro is also a synonym for bruno, the masculine equivalent of "brunette". Some scholars have posited that the name Moro came from Ludovico's coat of arms, which contained the mulberry tree (the fruit of which is called mora in Italian). Still others have posited that Maurus was simply Ludovico's second name.[2]

References

- Vezzosi, Alessandro (1997). Leonardo da Vinci: Renaissance Man. New Horizons. Translated by Bonfante-Warren, Alexandra (English translation ed.). London, UK: Thames & Hudson. p. 53. ISBN 978-0-500-30081-7.

- Cf. John E. Morby (1978). "The Sobriquets of Medieval European Princes". Canadian Journal of History. 13 (1): 13.

- Godfrey, F. M., "The Eagle and the Viper", History Today, Vol.3, Issue 10, September 1953

- "Ludovico il Moro e Beatrice d'Este", Palio di Mortara

- "Ludovico Sforza Moro", Biografia y Vidas

- Miller-Wald, P. (1897). "Beiträge zur Kenntnis des Leonardo da Vinci". Jahrbuch der Preußischen Kunstsammlungen. XVII: 78.

- Burckhardt, Jacob (1878). The Civilization Of The Renaissance in Italy. University of Toronto - Robarts Library: Vienna Phaidon Press. p. 23. Retrieved 28 February 2019.

- Durant, Will (1953). The Renaissance. The Story of Civilization. 5. New York: Simon and Schuster. p. 191.

- John Wilson (1832). History of Switzerland. Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown, Green, & Longman. p. 180.

- Bosisio, Alfredo (1998). "Ludovico Sforza". Encyclopædia Britannica (online). Retrieved 13 June 2015.

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Sforza". Encyclopædia Britannica. 24 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 756.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Sforza". Encyclopædia Britannica. 24 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 756.

Further reading

- Godfrey, F. M. "The Eagle and the Viper: Lodovico Il Moro of Milan: A Renaissance Tyrant." History Today (Oct 1953) 3#10 pp 705-715.

- Lodovico Sforza, in: Thomas Gale, Encyclopedia of World Biography, 2005–2006.

External links

- Portrait and family tree

- Leonardo's Itinerary: Early maturity in Milan (1482–1499), by Valentina Cupiraggi, trans. Catherine Frost.

| Italian nobility | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Gian Galeazzo Sforza |

Duke of Milan 1494–1499 |

Succeeded by Louis II |