Lugton

Lugton is a small village or hamlet in East Ayrshire, Scotland with a population of 80 people.[1] The A736 road runs through on its way from Glasgow, 15 miles (24.1 km) to the north, to Irvine in North Ayrshire. Uplawmoor is the first settlement on this 'Lochlibo Road' to the north and Burnhouse is to the south. The settlement lies on the Lugton Water which forms the boundary between East Ayrshire and East Renfrewshire as well as that of the parishes of Dunlop and Beith.

| Lugton | |

|---|---|

The Lochlibo Road looking towards Glasgow from the site of the old Lugton Inn. | |

Lugton Location within East Ayrshire | |

| Population | 80 (2001 Census) |

| OS grid reference | NS413529 |

| Council area | |

| Lieutenancy area | |

| Country | Scotland |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Police | Scotland |

| Fire | Scottish |

| Ambulance | Scottish |

| UK Parliament | |

| Scottish Parliament | |

History

In the 1830s the village consisted of only four houses: the hotel or inn, the smithy, and two toll houses. In 1845 the New Statistical Account records six other houses where spiritous liquors were sold. The road up from Uplawmoor was called the Lochlibo Road on the 1860s OS. The Lugton Inn was sadly destroyed by fire in the early 2000s. The name 'Lugton' is not marked on Timothy Pont's map of 1604.[2] Some of the Lugton area farms are indicated, with Waterlands, Duniflett, Biggart, Roshead (Ramshead), and Knokmend (Knockmade). A Waterland Mill is shown. Armstrong's map of 1775,[3] does not show Lugton or its farms and the only road passes Lochlibo from Glasgow and heads up through the Caldwell estate to Paisley. Thomson's 1820 map marks a 'Keepers Cottage' which may have been on the main entrance drive running to the main road. The Paraffin Lamp Inn is not marked on the 1860 OS, however it is present on the 1895 edition. It appears to have been called the 'Paraffin Lamp' for many years, prior to which it was a private dwelling with outbuildings. It had a piggery and smokehouse and when it became an inn the dwelling house continued its use as a private home. The old site of Halket Loch lies not far away, once located near the various Halket Farms and that of Lochridgehills Farm.

Turnpike

Lugton was on two toll roads or turnpikes; one going to Kilmarnock and Ayr and the other to Irvine. The Glasgow by Lugton, to Kilmarnock, Irvine and Ayr turnpike was completed in 1820 at the cost of £18,000.[4] The tollhouse on the Kilmarnock road stood opposite the stationmaster's house for Lugton station, the other still stands at the back of the site of the old Lugton Inn. It was later used as a smithy and is now a private dwelling. The nearby milestone read Beith 43⁄4; Ayr 223⁄4; Glasgow 14; and Irvine 111⁄4 miles.

| Etymology |

| Lugton comes from Ludgar or Lugdurr[5] and Ton. A Toun or Ton was a farm and its outbuildings.[6] The termination Durr is supposed by some to be of Celtic origin and may refer to 'black' or 'water'.[7] |

The name 'turnpike' originated from the original 'gate' used being just a simple wooden bar attached at one end to a hinge on the supporting post. The hinge allowed it to 'open' or 'turn' This bar looked like the 'pike' used as a weapon in the army at that time and therefore we get 'turnpike'. The term was also used by the military for barriers set up on roads specifically to prevent the passage of horses.

In addition to providing better surfaces and more direct routes, the turnpikes settled the confusion of the different lengths given to miles,[8] which varied from 4,854 to nearly 7,000 feet (2,100 m). Long miles, short miles, Scotch or Scot's miles (5,928 ft), Irish miles (6,720 ft), etc. all existed. 5,280 feet (1,610 m) seems to have been an average!

Another important point is that when these new toll roads were constructed the turnpike trusts went to a great deal of trouble to improve the route of the new road and these changes could be quite considerable as the old roads tended to go from farm to farm, hardly the shortest route. The tolls on roads were abolished in 1878 to be replaced by a road 'assessment', which was taken over by the county council in 1889.

Most milestones are no longer in-situ and often the only remaining clue is an otherwise unexplained 'kink' in the line of a hedgerow. The milestones were buried during the Second World War so as not to provide assistance to invading troops, German spies, etc.[9] This seems to have happened all over Scotland, however Fife was more fortunate than Ayrshire, for the stones were taken into storage and put back in place after the war had finished.[10]

Economy

In around 1850 iron ore deposits were found nearby and Messrs. Merry & Cunninghame, Ironmasters, built a row of houses for 200 people. John Cunninghame, at one point the sole proprietor, developed his business by taking loans out against the 'Lands of Chapeltoun', his home. He later became bankrupt and the estate was sequestered.[11] A brickworks was later established near Netherton farm at Horners Corner in the Castlewat plantation to use up the blaes bing produced in the mining of the iron ore, which had ceased in around 1900, but it in turn closed in 1921.[12] It was run by the Reid family.[13] A lime works had existed near Lugton as far back as 1829: it is shown on Aitken's map of Cunninghgame. A modern lime works was more recently established at the top of the belt of limestone, now worked out, by Reid of Halket and later sold to R. Howie & Sons in 1947.[13][14] Limestone is now brought to the site from elsewhere and the finished lime is used by farmers, in tarmacadam, previously in the manufacture of pig iron, etc. It had been used as 'Davy Dust' to help settle the coal dust in the mines.[13]

Jamieson records that the inn at Burnhouse was nicknamed the 'Trap 'Em Inn', the one at Lugton was called the 'Lug 'Em Inn', that at Auchentiber the 'Cleek 'Em Inn', and finally the one at Torranyard was called the 'Turn 'Em Out.'[15]

A large number of small limestone quarries ware marked on the 1860 OS with several limekilns. Waterland corn mill on the Lugton Water is still marked on the 1895 map, with Tree Well nearby. Highgate wauk mill still survives as a dwelling (2007).

A creamery was opened in 1919, dispatching milk to Glasgow by train and making cheese which was matured at the manager's house; also known as "Jeely Jocks" when jams were made from turnips and other vegetables during the first world war. It closed in 1919. Lugton Garage was run by Angie and Angus Robertson.[16]

Transport

It was once served by two railway stations, both of which are now closed. Lugton railway station was on the Glasgow, Barrhead and Kilmarnock Joint Railway's line, opening in 1871 and closed to passengers in 1966. The best known porter at Lugton station was local lady Peggy Speirs of Burnside Cottages. The Lanarkshire and Ayrshire Railway's Lugton station opened in 1903 and its line ran to Ardrossan from Glasgow. The station closed 4 July 1932.[17]

A live railway emergency exercise at Lugton in Ayrshire in 2000 played a vital part in the ongoing process of protecting Scotland’s rail passengers. The exercise simulated a collision between two passenger trains carrying 270 passengers. The aim was to test the emergency services’ response and management co-ordination by replicating real accident conditions as closely as possible. Strathclyde police co-ordinated the exercise in conjunction with the rail industry in Scotland, the British Transport Police, Civil Police, Scottish Ambulance Service, Fire Brigade, local authorities and Government emergency planning co-ordinators.[18]

Landmarks

'Lugton Hall' or Church

A small mission hall or church, also serving as a public hall, used to exist near the railway bridge until the 1980s, having been moved from its previous site near the old brickworks. It had two commodious ante-rooms, electric power and even central heating as early as 1935. Services were held fortnightly. The Lugton Discussion Society also held its meetings here. The building, a typical 'kit build' corrugated iron structure, survived until the 1990s, having gone out of use in the 1960s.[19] The site is now occupied by a private dwelling. The Lugton Hall was given to Lugton by Lady Mure of Caldwell.[20]

Lugton School

In 1897 the small school stood close to the north bank of the Lugton Water behind the smithy which had originally been the toll house.[21]

Caldwell mansion, estate and castle

The old castle of Caldwell sat on a knoll of the sloping hill-side to the south-west of Lochlibo. Only one tower remained as a prominent landmark after the times of the Covenanters and today's (2007) surviving tower is this same remnant. A new mansion house was built around 1712 by William Mure on the lands of Ramshead, however the present Robert Adam designed house was built by his son, William 'Baron Mure' about 200 yards (180 m) lower down from the original. Caldwell House was the Mure family home until 1909.

Antiquities

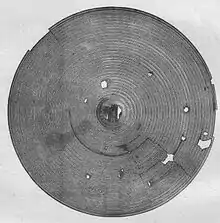

In about 1770 half a dozen bronze bucklers (small shields) were dug out of a moss on Lugton ridge. They were found about 7-foot (2.1 m) down and were arranged in a circle. One was preserved, measuring nearly 27 inches (690 mm) in diameter, with a semi-globular 'umbo' or 'boss'[7] being just over 4 inches (100 mm) in diameter. It is highly ornamented, with twenty nine concentric rings with intervening ribs.[23]

The Lugton Water

This rivulet runs 14 miles (23 km) from Loch Libo (395 feet above sea-level) through Neilston, Beith, Dunlop, Stewarton, and Kilwinning parishes, until having passed through Eglinton Country Park it runs into the Garnock, 2 and a half miles north by west of Irvine town. It contains fresh-water and sea-trout and the occasional salmon. Pont refers to it as the 'Ludgar' or 'Lugdurr'[5] Loch Libo in the 14th century was referred to as Loch le Bog Syde in a charter, meaning the Bogside Loch.[24]

The Duniflat burn joins the Lugton Water from the East Ayrshire side close to the North Biggart bridge near where the Bells burn from Bells Bog on the East Renfrewshire side also has its confluence.

Waterland Mill

Dobie records that in 1648 John Porterfield succeeded his father as the male heir to the seventh part of the lands of Waterland including a seventh part of the corn mill.[25] The mill stood on the Lugton Water near the Lugton or Waterland Spout (waterfall) and in 1857 was shown on the Ordnance Survey map as still in use although part of the detached ancillary buildings was a ruin. By 1897 the OS maps show that the whole complex was abandoned.

Views in and around Lugton

The Limeworks.

The Limeworks. Looking across the Stewarton and Dunlop Road near the junction with the main road. 2007.

Looking across the Stewarton and Dunlop Road near the junction with the main road. 2007. The old Tollhouse for the Glasgow to Irvine road. Later used a part of a smithy.

The old Tollhouse for the Glasgow to Irvine road. Later used a part of a smithy. The Lugton Water looking towards Caldwell.

The Lugton Water looking towards Caldwell.

The old 1873 'Lugton' Stationmaster's house.

The old 1873 'Lugton' Stationmaster's house. The old 1903 'Lugton High' Stationmaster's house.

The old 1903 'Lugton High' Stationmaster's house. The old 1903 'Lugton High' Stationmaster's house on the left and the much altered railway workers houses on the right.

The old 1903 'Lugton High' Stationmaster's house on the left and the much altered railway workers houses on the right. The remains of the wooden pedestrian footbridge and way up to Lugton High station.

The remains of the wooden pedestrian footbridge and way up to Lugton High station.

Lugton traditions and local history

A local tradition was that an underground passage ran from the inn to Caldwell House, however a search by owners in the cellars never revealed any signs of a hidden passage.[26]

The village is celebrated in the songs of folk music group Nyah Fearties, whose members hail from Lugton.

Near the hamlet is Lugton quarry, which features in many geology textbooks for its marine fossils preserved in the Carboniferous rock. [27]

James Richmond, aged 46, was killed when he was struck by a railway locomotive on 1 October 1870 on the line near the Lugton Viaduct.

The Lugton Ridges were part of the Barony of Giffen in the Parish of Beith. One of these ridges also had the name of Deepstone.[28]

Halket or Hawkhead Loch, now drained, covered about 10 acres (40,000 m2) and was drained in the 1840s. It is shown on the early maps of Ayrshire, such as Timothy Pont's map of 1604.[2] Above it in 1820 was a dwelling with the unlikely name of 'Lions Den', possibly a corruption of 'Linn' as the farm of Linnhead is in the vicinity.

References

- East Ayrshire Council Archived 2007-03-27 at the Wayback Machine

- Pont, Timothy (1604). Cuninghamia. Pub. Blaeu in 1654.

- Armstrong and Son. Engraved by S.Pyle (1775). A New Map of Ayr Shire comprehending Kyle, Cunningham and Carrick.

- Pride, David (1910). A History of the Parish of Neilston. Pub. Alexander Gardner, Paisley. P. 109.

- Dobie, James D. (ed Dobie, J.S.) (1876). Cunninghame, Topographized by Timothy Pont 1604–1608, with continuations and illustrative notices. Pub. John Tweed, Glasgow. P. 313.

- Warrack, Alexander (1982)."Chambers Scots Dictionary". Chambers. ISBN 0-550-11801-2.

- Local History Dictionary

- Thomson, John (1828). A Map of the Northern Part of Ayrshire.

- Wilson, Jenny (2006). Oral communication with Griffith, R.S.Ll.

- Stephen, Walter M. (1967-68). Milestones and Wayside Markers in Fife. Proc Soc Antiq Scot, V.100. P. 184.

- Chapeltoun Mains Archive (2007) - legal documents of the 'Lands of Chapelton' from 1709 onwards.

- Milligan, Susan. Old Stewarton, Dunlop and Lugton. Pub. Ochiltree. ISBN 1-84033-143-7.

- Dunlop Ancient & Modern. An Exhibition. March 1998. Editor. Dugald Campbell. p. 14.

- Strawhorn, John and Boyd, William (1951). The Third Statistical Account of Scotland. Ayrshire.

- Jamieson, Shiela (1997). Our Village. Greenhills WRI. Page 18

- Dunlop Ancient & Modern. An Exhibition. March 1998. Editor. Dugald Campbell. p. 16.

- Milligan, Susan. Old Stewarton, Dunlop and Lugton. Stenlake Publishing. ISBN 1-84033-1437. P. 32 - 33.

- Live railway accident exercise. Archived 2007-09-28 at the Wayback Machine

- Dunlop Ancient & Modern. An Exhibition. March 1998. Editor. Dugald Campbell. p. 15.

- Bayne, John F. (1935). Dunlop Parish - A History of Church, Parish, and Nobility. Pub. T.& A. Constable, P. 126.

- Ayrshire VIII.12, Revised: 1895, Published: 1897

- Pride, David (1910), A History of the Parish of Neilston. Pub. Alexander Gardner, Paisley. Facing P. 128.

- Smith, John (1895). Prehistoric Man in Ayrshire. Pub. Elliot Stock. P. 81 - 82.

- Paterson, James (1863-66). History of the Counties of Ayr and Wigton. V. III - Cunninghame. J. Stillie. Edinburgh. P. 215.

- Dobie, James D. (ed Dobie, J.S.) (1876). Cunninghame, Topographized by Timothy Pont 1604–1608, with continuations and illustrative notices. Glasgow: John Tweed. P. 206

- Borland, Lindsey (2006). Oral communication to Griffith, Roger S. Ll.

- Fossils from Lugton Quarry.

- Dobie, James D. (ed Dobie, J.S.) (1876). Cunninghame, Topographized by Timothy Pont 1604–1608, with continuations and illustrative notices. Pub. John Tweed, Glasgow. P. 318.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lugton. |

- Video and commentary on Halket Loch and Craighead Law

- YouTube video of the old Lugton horse trough

- YouTube video of the Waterland Mill and Spout

- YouTube video of the Lugton or Waterland Spout

- Maps at the National Library of Scotland

- 1860 OS Maps

- Places called Lugton

- A Researcher's Guide to Local History terminology