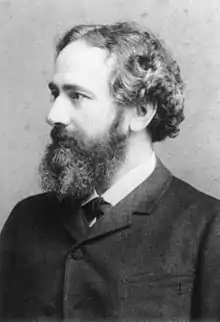

Lujo Brentano

Ludwig Joseph Brentano (/brɛnˈtɑːnoʊ/; German: [bʁɛnˈtaːno]; 18 December 1844 – 9 September 1931) was an eminent German economist and social reformer.

Lujo Brentano | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 18 December 1844 |

| Died | 9 September 1931 (aged 86) München, Germany |

| Alma mater | University of Göttingen (Ph.D.) Trinity College Dublin |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Economist |

| Institutions | University of Munich |

| Doctoral advisor | Adolph Wagner (Habitilation) Johann von Helferich (Ph.D.) |

| Doctoral students | Theodor Heuss Robert Kuczynski Werner Hegemann Fukuda Tokuzō Hans Ehrenberg |

Biography

Lujo Brentano, born in Aschaffenburg into a distinguished German Roman Catholic intellectual family (originally of Italian descent),[1] attended school in Augsburg and Aschaffenburg. He studied in Dublin (Trinity College), Münster, Munich, Heidelberg (doctorate in law), Würzburg, Göttingen (doctorate in economics), and Berlin (habilitation in economics, 1871).

He was a professor of economics and state sciences at the universities of Breslau, Strasbourg, Vienna, Leipzig, and most importantly, Munich (1891–1914). With Ernst Engel, the statistician, he made an investigation of the English trade unions.[2]

In 1872, he became involved in an extended dispute with Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. Brentano accused Marx of falsifying a quotation from an 1863 speech by William Gladstone.[3]

In 1914, he signed the Manifesto of the Ninety-Three. After the revolution of November 1918, he served in minister-president Kurt Eisner's government of the People's State of Bavaria as People's Commissar (Minister) for Trade, but only for some days in December 1918.

Brentano died in Munich in 1931, aged 86.

Legacy

Brentano was a Kathedersozialist (reform-minded) and a founding member of the Verein für Socialpolitik. His influence on the social market economy, and on many Germans who would be leaders just after the end of World War II, can hardly be overrated. He also influenced later economists, such as his doctoral student Arthur Salz.

Note: It is often mistakenly claimed that Brentano was called Ludwig Joseph, and that "Lujo" was a kind of nickname or contraction. This is incorrect; while he was given his name after a Ludwig and a Joseph, Lujo was his real and legal first name. (See his autobiography, Mein Leben..., below, p. 18.)

Bibliography

- Brentano, Lujo (1871–72). Die Arbeitergilden der Gegenwart. 2 vols., Leipzig: Duncker und Humblot. (English: On the History and Development of Gilds and the Origins of Trade Unions. 1870.)

- Brentano, Lujo (1901). Ethik und Volkswirtschaft in der Geschichte. November 1901. München: Wolf.

- Brentano, Lujo (1910). "The Doctrine of Malthus and the Increase of Population During the Last Decades." Economic Journal vol. 20(79), pp. 371–93.

- Brentano, Lujo (1923). Der wirtschaftende Mensch in der Geschichte. Leipzig: Meiner. Reprint Marburg: Metropolis, 200ß.

- Brentano, Lujo (1924). Wege zur Verständigung - Der Judenhass. Berlin, Philo Verlag und Buchhandlung

- Brentano, Lujo (1927–29). Eine Geschichte der wirtschaftlichen Entwicklung Englands. 4 vols., Jena: Gustav Fischer.

- Brentano, Lujo (1929). Das Wirtschaftsleben der antiken Welt. Jena: Fischer.

- Brentano, Lujo (1931). Mein Leben im Kampf um die soziale Entwicklung Deutschlands. Jena: Diederichs. Reprint Marburg: Metropolis, 2004.

- Brentano, Lujo (1924). Konkrete Bedingungen der Volkswirtschaft. Leipzig: Meiner. 1924. Reprint Marburg: Metropols, 2003.

- Brentano, Lujo (1877–1924). Der tätige Mensch und die Wissenschaft von der Wirtschaft. Reprint Marburg: Metropolis, 2006.

- Essays, including "The Industrialist".[4]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lujo Brentano. |

| Wikisource has the text of a 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article about Lujo Brentano. |

References

- Lujo Brentano was the son of the writer Christian Brentano, nephew of writers Clemens Brentano and Bettina von Arnim, two major figures in the romantic movement in German literature, and the brother of Franz Brentano, a philosopher whose students included Edmund Husserl, Alexius Meinong and Sigmund Freud, among others.

- Gilman, D. C.; Peck, H. T.; Colby, F. M., eds. (1905). . New International Encyclopedia (1st ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead.

- Friedrich Engels, In the Case of Brentano vs. Marx - Regarding Alleged Faslifications of Quotation: The Story and Documents. (1891)

- Rudolf Steiner, Education as a Force for Social Change, Anthroposophic Press, 1997, Lecture 1 (Dornach / August 9, 1919): "I recently mentioned the example of the famous professor Lujo Brentano, a leading modern economist in Middle Europe who recently wrote an article entitled “The Industrialist.” In it he develops three characteristics of an industrialist."