Lumbar vertebrae

The lumbar vertebrae are, in human anatomy, the five vertebrae between the rib cage and the pelvis. They are the largest segments of the vertebral column and are characterized by the absence of the foramen transversarium within the transverse process (since it is only found in the cervical region) and by the absence of facets on the sides of the body (as found only in the thoracic region). They are designated L1 to L5, starting at the top. The lumbar vertebrae help support the weight of the body, and permit movement.

| Lumbar vertebrae | |

|---|---|

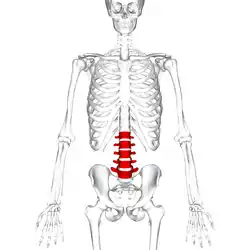

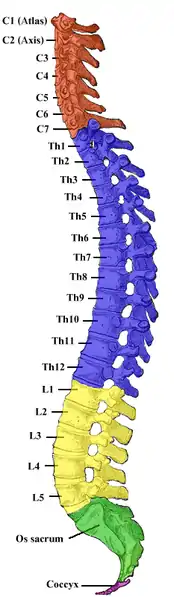

Position of human lumbar vertebrae (shown in red). It consists of 5 bones, from the top down, L1, L2, L3, L4 and L5. | |

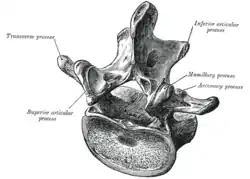

A typical lumbar vertebra | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | vertebrae lumbales |

| MeSH | D008159 |

| TA98 | A02.2.04.001 |

| TA2 | 1067 |

| FMA | 9921 |

| Anatomical terms of bone | |

Human anatomy

General characteristics

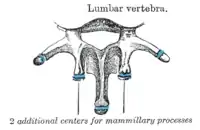

The figure on the left depicts the general characteristics of the first through fourth lumbar vertebrae. The fifth vertebra contains certain peculiarities, which are detailed below.

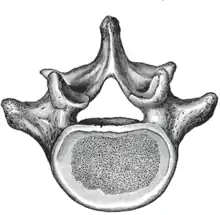

As with other vertebrae, each lumbar vertebra consists of a vertebral body and a vertebral arch. The vertebral arch, consisting of a pair of pedicles and a pair of laminae, encloses the vertebral foramen (opening) and supports seven processes.

Body

The vertebral body of each lumbar vertebra is large, wider from side to side than from front to back, and a little thicker in front than in back. It is flattened or slightly concave above and below, concave behind, and deeply constricted in front and at the sides.[1]

Arch

The pedicles are very strong, directed backward from the upper part of the vertebral body; consequently, the inferior vertebral notches are of considerable depth.[1] The pedicles change in morphology from the upper lumbar to the lower lumbar. They increase in sagittal width from 9 mm to up to 18 mm at L5. They increase in angulation in the axial plane from 10 degrees to 20 degrees by L5. The pedicle is sometimes used as a portal of entrance into the vertebral body for fixation with pedicle screws or for placement of bone cement as with kyphoplasty or vertebroplasty.

The laminae are broad, short, and strong.[1] They form the posterior portion of the vertebral arch. In the upper lumbar region the lamina are taller than wide but in the lower lumbar vertebra the lamina are wider than tall. The lamina connects the spinous process to the pedicles.

The vertebral foramen within the arch is triangular, larger than the thoracic vertebrae, but smaller than in the cervical vertebrae.[1]

Processes

The spinous process is thick, broad, and somewhat quadrilateral; it projects backward and ends in a rough, uneven border, thickest below where it is occasionally notched.[1]

The superior and inferior articular processes are well-defined, projecting respectively upward and downward from the junctions of pedicles and laminae. The facets on the superior processes are concave, and look backward and medialward; those on the inferior are convex, and are directed forward and lateralward. The former are wider apart than the latter since in the articulated column, the inferior articular processes are embraced by the superior processes of the subjacent vertebra.[1]

The transverse processes are long and slender. They are horizontal in the upper three lumbar vertebrae and incline a little upward in the lower two. In the upper three vertebrae they arise from the junctions of the pedicles and laminae, but in the lower two they are set farther forward and spring from the pedicles and posterior parts of the vertebral bodies. They are situated in front of the articular processes instead of behind them as in the thoracic vertebrae, and are homologous with the ribs.[1]

Three portions or tubercles can be noticed in a transverse process of a lower lumbar vertebrae: the lateral or costiform process, the mammillary process, and the accessory process.[2] The costiform is lateral, the mammillary is superior (cranial), and the accessory is inferior (caudal). The mammillary is connected in the lumbar region with the back part of the superior articular process. The accessory process is situated at the back part of the base of the transverse process. The tallest and thickest costiform process is usually that of L5.[2]

First and fifth lumbar vertebrae

The first lumbar vertebra is level with the anterior end of the ninth rib. This level is also called the important transpyloric plane, since the pylorus of the stomach is at this level. Other important structures are also located at this level, they include; fundus of the gall bladder, celiac trunk, superior mesenteric artery, termination of spinal cord, beginning of filum terminalis, renal vessels, middle suprarenal arteries, and hila of kidneys.

The fifth lumbar vertebra is characterized by its body being much deeper in front than behind, which accords with the prominence of the sacrovertebral articulation; by the smaller size of its spinous process; by the wide interval between the inferior articular processes, and by the thickness of its transverse processes, which spring from the body as well as from the pedicles.[1] The fifth lumbar vertebra is by far the most common site of spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis.[3]

Most individuals have five lumbar vertebrae, while some have four or six. Lumbar disorders that normally affect L5 will affect L4 or L6 in these latter individuals.

Segmental movements

The range of segmental movements in a single segment is difficult to measure clinically, not only because of variations between individuals, but also because it is age and sex dependent. Furthermore, flexion and extension in the lumbal spine is the product of a combination of rotation and translation in the sagittal plane between each vertebra.[4]

Ranges of segmental movements in the lumbar spine (White and Punjabi, 1990) are (in degrees): [5]

| L1-L2 | L2-L3 | L3-L4 | L4-L5 | L5-S1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flexion/ Extension | 12° | 14° | 15° | 16° | 17° |

| Lateral flexion | 6° | 6° | 8° | 6° | 3° |

| Axial rotation | 2° | 2° | 2° | 2° | 1° |

Congenital anomalies

Congenital vertebral anomalies can cause compression of the spinal cord by deforming the vertebral canal or causing instability.

Lumbarization of sacral vertebra 1, seen as 6 vertebrae that do not connect to ribs.

Lumbarization of sacral vertebra 1, seen as 6 vertebrae that do not connect to ribs. Sacralization of the L5 vertebra is seen at the lower right of the image.

Sacralization of the L5 vertebra is seen at the lower right of the image. Congenital block vertebra of the lumbar spine. CT volume rendering.

Congenital block vertebra of the lumbar spine. CT volume rendering.

Other animals

African apes have three and four lumbar vertebrae, (bonobos have longer spines with an additional vertebra) and humans normally five. This difference, and because the lumbar spines of the extinct Nacholapithecus (a Miocene hominoid with six lumbar vertebrae and no tail) are similar to those of early Australopithecus and early Homo, it is assumed that the Chimpanzee-human last common ancestor also had a long vertebral column with a long lumbar region and that the reduction in the number of lumbar vertebrae evolved independently in each ape clade. [6] The limited number of lumbar vertebrae in chimpanzees and gorillas result in an inability to lordose (curve) their lumbar spines, in contrast to the spines of Old World monkeys and Nacholapithecus and Proconsul, which suggests that the last common ancestor was not "short-backed" as previously believed. [7]

Additional images

Position of lumbar vertebrae (shown in red). Animation.

Position of lumbar vertebrae (shown in red). Animation. Same as the left. Bones around the lumbar vertebrae are shown as semi-transparent.

Same as the left. Bones around the lumbar vertebrae are shown as semi-transparent. Shape of lumbar vertebrae (shown in blue and yellow). Animation.

Shape of lumbar vertebrae (shown in blue and yellow). Animation. 3D image of a lumbar vertebra

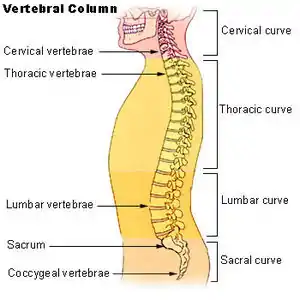

3D image of a lumbar vertebra Vertebral column.

Vertebral column. Muscles of the iliac and anterior femoral regions. First lumbar vertebra second highest vertebra seen.

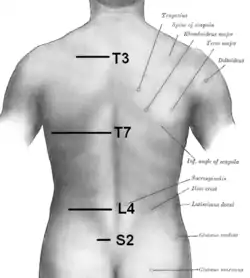

Muscles of the iliac and anterior femoral regions. First lumbar vertebra second highest vertebra seen. Orientation of vertebral column on surface. T3 is at level of medial part of spine of scapula. T7 is at inferior angle of the scapula. L4 is at highest point of iliac crest. S2 is at the level of posterior superior iliac spine. Furthermore, C7 is easily localized as a prominence at the lower part of the neck.[8]

Orientation of vertebral column on surface. T3 is at level of medial part of spine of scapula. T7 is at inferior angle of the scapula. L4 is at highest point of iliac crest. S2 is at the level of posterior superior iliac spine. Furthermore, C7 is easily localized as a prominence at the lower part of the neck.[8] Vertebral column

Vertebral column Illustration highlighting lumbar spine.

Illustration highlighting lumbar spine. A lumbar vertebra seen from the side

A lumbar vertebra seen from the side Ossification of lumbar vertebrae

Ossification of lumbar vertebrae

See also

References

This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 104 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

- Gray's Anatomy (1918), see infobox

- Postacchini, Franco (1999) Lumbar Disc Herniation p.19

- Eizenberg, N. et al. (2008). General Anatomy: Principles and Applications, p. 17.

- Hansen; et al. (2006). "Anatomy and Biomechanics of the Back Muscles in the Lumbar Spine With Reference to Biomechanical Modeling". Spine. Medscape. 31 (17): 1888–99. doi:10.1097/01.brs.0000229232.66090.58. PMID 16924205. S2CID 43352264. Archived from the original on November 14, 2010.

- Hansen; et al. (2006). "Ranges of Segmental Motion for the Lumbar Spine". Medscape. Archived from the original on July 5, 2015.

- McCollum, MA; Rosenman, BA; Suwa, G; Meindl, RS; Lovejoy, CO (March 15, 2010). "The vertebral formula of the last common ancestor of African apes and humans". Journal of Experimental Zoology Part B: Molecular and Developmental Evolution. 314 (2): 123–34. doi:10.1002/jez.b.21316. PMID 19688850. (Abstract)

- Lovejoy, C. Owen; McCollum, Melanie A. (October 27, 2010). "Spinopelvic pathways to bipedality: why no hominids ever relied on a bent-hip-bent-knee gait". Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 365 (1556): 3289–99. doi:10.1098/rstb.2010.0112. PMC 2981964. PMID 20855303. (Introduction)

- Anatomy Compendium (Godfried Roomans and Anca Dragomir)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lumbar vertebrae. |

- "Lower Back Pain Condition, Treatment and Exercise". SpineUniverse. Retrieved February 15, 2017.

- "Virtual Spine — Online Learning Resource". Toronto Western Hospital Department of Anesthesia and Pain Management. Retrieved February 15, 2017.