Lymnaea stagnalis

Lymnaea stagnalis, better known as the great pond snail, is a species of large air-breathing freshwater snail, an aquatic pulmonate gastropod mollusk in the family Lymnaeidae.

| Great Pond Snail Lymnaea stagnalis | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| (unranked): | |

| Superfamily: | |

| Family: | |

| Subfamily: | Lymnaeinae |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | L. stagnalis |

| Binomial name | |

| Lymnaea stagnalis | |

Limnaea stagnalis var. baltica Lindström, 1868: synonym of Lymnaea stagnalis (Linnaeus, 1758)

Distribution

The distribution of this species is Holarctic. It is widely distributed, and is common in many countries and islands including: Belgium, British Isles: Great Britain and Ireland, Canada (Alberta province, Ottawa valley), Cambodia, Czech Republic[3] – least concern (LC),[4] Germany – distributed in whole Germany but in 2 states in red list (Rote Liste BRD),[5] Netherlands,[6] Poland, Russia, Slovakia,[3] Sweden (Skåne), Switzerland, Ukraine. United States (Utah) – Lymnaea stagnalis appressa.[7]

Shell description

For terms see gastropod shell The height of an adult shell of this species ranges from 45–60 mm. The width of an adult shell ranges from 20–30 mm. (34) mm.

The 40–50 x 22–30 mm. (median) shell has 4.5–6 weakly convex whorls. The upper whorls are pointed, the last whorl is suddenly inflated, so that its diameter is more than a continuous increase of that of the upper whorls. The umbilicus is closed. Shells are brown in colour.[8]

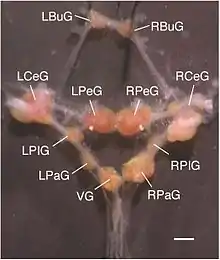

Nervous system

LBuG and RBuG: left and right buccal ganglia

LCeG and RCeG: left and right cerebral ganglia

LPeG and RPeG: left and right pedal ganglia

LPIG and RPIG: left and right pleural ganglia

LPaG and RPaG: left and right parietal ganglia

VG: visceral ganglion.

Lymnaea stagnalis is widely used for the study of learning, memory and neurobiology.[9]

Lymnaea stagnalis has a relatively simple central nervous system (CNS) consisting of a total of ~20,000 neurons, many of them individually identifiable, organized in a ring of interconnected ganglia. Most neurons of the Lymnaea stagnalis central nervous system are large in size (diameter: up to ~100 μm), thus allowing electrophysiological dissection of neuronal networks that has yielded profound insights in the working mechanisms of neuronal networks controlling relatively simple behaviors such as feeding, respiration, locomotion, and reproduction. Studies using the central nervous system of Lymnaea stagnalis as a model organism have also identified novel cellular and molecular mechanisms in neuronal regeneration, synapse formation, synaptic plasticity, learning and memory formation, the neurobiology of development and aging, the modulatory role of neuropeptides, and adaptive responses to hypoxic stress.[9]

Habitat

This large snail lives only in freshwater: it prefers slowly running water, and standing water bodies.

Life cycle

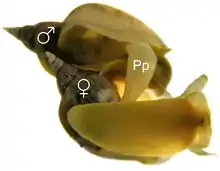

Lymnaea stagnalis is a simultaneously hermaphroditic species and can mate in the male and female role, but within one copulation only one sexual role is performed at a time.[11] Lymnaea stagnalis perform more inseminations in larger groups and prefer to inseminate novel over familiar partners. Such higher motivation to copulate when a new partner is encountered is known as the Coolidge effect and has been demonstrated in hermaphrodites firstly in 2007.[11]

Parasites

Lymnaea stagnalis is an intermediate host for:

Other parasites of Lymnaea stagnalis include:

- Echinoparyphium aconiatum[13]

- Echinoparyphium recurvatum[14]

- Opisthioglyphe ranae[14]

- Plagiorchis elegans[14]

- Diplostomum pseudospathaceum[14]

- Echinostoma revolutum[14]

- Trichobilharzia szidati[14]

Lymnaea stagnalis has been experimentally infected with Elaphostrongylus rangiferi.[15]

References

This article incorporates CC-BY-2.0 text from references[9][11] and CC-BY-2.5 text from the reference[10]

- Seddon, M.B.; Van Damme, D. & Cordeiro, J. (2017). "Lymnaea stagnalis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2017. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-3.RLTS.T155475A42428297.en.

- Linnaeus C. (1758) Systema Naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. 10th edition. Vermes. Testacea: 700–781. Holmiae. (Salvius).

- (in Czech) Horsák M., Juřičková L., Beran L., Čejka T. & Dvořák L. (2010). "Komentovaný seznam měkkýšů zjištěných ve volné přírodě České a Slovenské republiky. [Annotated list of mollusc species recorded outdoors in the Czech and Slovak Republics]". Malacologica Bohemoslovaca, Suppl. 1: 1–37. PDF.

- Juřičková L., Horsák M. & Beran L. (2001) "Check-list of the molluscs (Mollusca) of the Czech Republic". Acta Soc. Zool. Bohem. 65: 25–40.

- Glöer P. & Meier-Brook C. (2003) Süsswassermollusken. DJN, 134 pp., p. 109, ISBN 3-923376-02-2.

- (in Dutch) Lymnaea stagnalis — Anemoon

- "Lymnaea stagnalis". Utah Division of Wildlife Resources. Archived from the original on 19 May 2017. Retrieved 19 May 2017.

- Animalbase (Welter-Schultes)

- Feng Z-P., Zhang Z., Kesteren R. E. van, Straub V. A., Nierop P. van, Jin K., Nejatbakhsh N., Goldberg J. I., Spencer G. E., Yeoman M. S., Wildering W., Coorssen J. R., Croll R. P., Buck L. T., Syed N. I. & Smit A. B. (23 September 2009) "Transcriptome analysis of the central nervous system of the mollusc Lymnaea stagnalis". BMC Genomics 10: 451. doi:10.1186/1471-2164-10-451

- Koene J. M., Sloot W., Montagne-Wajer K., Cummins S. F., Degnan B. M., Smith J. S., Nagle G. T. & Maat A. ter (2010). "Male Accessory Gland Protein Reduces Egg Laying in a Simultaneous Hermaphrodite". PLoS ONE 5(4): e10117. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0010117.

- Koene J. M. & Maat A. T. (6 November 2007) "Coolidge effect in pond snails: male motivation in a simultaneous hermaphrodite". BMC Evolutionary Biology 7: 212. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-7-212

- Kudlai O. S. (2009). "The discovery of the intermediate host for the trematode Moliniella anceps (Trematoda, Echinostomatidae) in Ukraine". Vestnik zoologii 43(4): e-11–e-13. doi:10.2478/v10058-009-0014-x.

- Leicht K. & Seppälä O. (2014). "Infection success of Echinoparyphium aconiatum (Trematoda) in its snail host under high temperature: role of host resistance". Parasites & Vectors 7:192. doi:10.1186/1756-3305-7-192.

- Soldanova M., Selbach C., Sures B., Kostadinova A. & Perez-del-Olmo A. (2010). "Larval trematode communities in Radix auricularia and Lymnaea stagnalis in a reservoir system of the Ruhr River". Parasites & Vectors 2010, 3: 56. doi:10.1186/1756-3305-3-56.

- Skorping A. (1985). "Lymnea stagnalis as experimental intermediate host for Elaphostrongylus rangiferi". Zeitschrift fur Parasitenkunde 71: 265–270.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lymnaea stagnalis. |

- Lymnaea stagnalis at Animalbase taxonomy,short description, distribution, biology,status (threats), images

- Hoffer J. N. A., Ellers J. & Koene J. M. (2010). "Costs of receipt and donation of ejaculates in a simultaneous hermaphrodite". BMC Evolutionary Biology 10: 393. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-10-393.

- Lymnaea – Scholarpedia article

- https://web.archive.org/web/20090925182719/http://www.lymnaea.org/ – Lymnaea stagnalis Sequencing Consortium

- Arnaud Giusti, Pierre Leprince, Gabriel Mazzucchelli, Jean-Pierre Thomé, Laurent Lagadic, Virginie Ducrot, Célia Joaquim-Justo : Proteomic Analysis of the Reproductive Organs of the Hermaphroditic Gastropod Lymnaea stagnalis Exposed to Different Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals; PLOS|ONE 19 November 2013