Macedonian Wars

The Macedonian Wars (214–148 BC) were a series of conflicts fought by the Roman Republic and its Greek allies in the eastern Mediterranean against several different major Greek kingdoms. They resulted in Roman control or influence over the eastern Mediterranean basin, in addition to their hegemony in the western Mediterranean after the Punic Wars. Traditionally, the "Macedonian Wars" include the four wars with Macedonia, in addition to one war with the Seleucid Empire, and a final minor war with the Achaean League (which is often considered to be the final stage of the final Macedonian war). The most significant war was fought with the Seleucid Empire, while the war with Macedonia was the second, and both of these wars effectively marked the end of these empires as major world powers, even though neither of them led immediately to overt Roman domination.[1] Four separate wars were fought against the weaker power, Macedonia, due to its geographic proximity to Rome, though the last two of these wars were against haphazard insurrections rather than powerful armies.[2] Roman influence gradually dissolved Macedonian independence and digested it into what was becoming a leading global empire. The outcome of the war with the now-deteriorating Seleucid Empire was ultimately fatal to it as well, though the growing influence of Parthia and Pontus prevented any additional conflicts between it and Rome.[2]

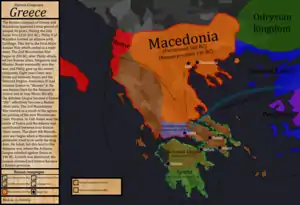

|

Macedonia and their environs. Circa 200 BC. |

From the close of the Macedonian Wars until the early Roman Empire, the eastern Mediterranean remained an ever shifting network of polities with varying levels of independence from, dependence on, or outright military control by, Rome.[3] According to Polybius,[4] who sought to trace how Rome came to dominate the Greek east in less than a century, Rome's wars with Greece were set in motion after several Greek city-states sought Roman protection against the Macedonian Kingdom and Seleucid Empire in the face of a destabilizing situation created by the weakening of Ptolemaic Egypt.[5]

In contrast to the west, the Greek east had been dominated by major empires for centuries, and Roman influence and alliance-seeking led to wars with these empires that further weakened them and therefore created an unstable power vacuum that only Rome was capable of pacifying.[6] This had some important similarities (and some important differences) to what had occurred in Italy centuries earlier, but was this time on a continental scale. Historians[7] see the growing Roman influence over the east, as with the west, not as a matter of intentional empire-building, but constant crisis management narrowly focused on accomplishing short-term goals within a highly unstable, unpredictable, and inter-dependent network of alliances and dependencies.[8] With some major exceptions of outright military rule (such as parts of mainland Greece), the eastern Mediterranean world remained an alliance of independent city-states and kingdoms (with varying degrees of independence, both de jure and de facto) until it transitioned into the Roman Empire.[9] It wasn't until the time of the Roman Empire that the eastern Mediterranean, along with the entire Roman world, was organized into provinces under explicit Roman control.[10]

First Macedonian War (214 to 205 BC)

During the Second Punic War, Philip V of Macedon allied himself with Hannibal.[11][12] Fearing possible reinforcement of Hannibal by Macedon, the senate dispatched a praetor with forces across the Adriatic. Roman maniples (aided by allies from the Aetolian League and Pergamon after 211 BC) did little more than skirmish with Macedonian forces and seize minor territory along the Adriatic coastline in order to "combat piracy". Rome's interest was not in conquest, but in keeping Macedon busy while Rome was fighting Hannibal. The war ended indecisively in 205 BC with the Treaty of Phoenice. While a minor conflict, it opened the way for Roman military intervention in Macedon. This conflict, though fought between Rome and Macedon, was largely independent of the Roman-Macedon wars that followed (which began with the Second Macedonian War and were largely dependent on each other) in the next century.[13]

Second Macedonian war (200 to 196 BC)

The past century had seen the Greek world dominated by the three primary successor kingdoms of Alexander the Great's empire: Ptolemaic Egypt, Macedonia and the Seleucid Empire. The imperial ambitions of the Seleucids after 230 BC were particularly destabilizing. The Seleucids set out to conquer Egypt, and Egypt responded through a major mobilization campaign. This campaign led to military victory against Seleucid incursions, but in 205 BC when Ptolemy IV was succeeded by the five-year-old Ptolemy V (or rather, by his regents), the newly armed Egyptians turned against each other. The result was a major civil war between north and south. Seeing that all of Egypt could now be conquered easily, the Macedonians and Seleucids forged an alliance to conquer and divide Egypt between themselves.[14]

This represented the most significant threat to the century-old political order that had kept the Greek world in relative stability, and in particular represented a major threat to the smaller Greek kingdoms which had remained independent. As Macedonia and the Seleucid Empire were the problem, and Egypt the cause of the problem, the only place to turn was Rome. This represented a major change, as the Greeks had recently shown little more than contempt towards Rome, and Rome little more than apathy towards Greece. Ambassadors from Pergamon and Rhodes brought evidence before the Roman Senate that Philip V of Macedon and Antiochus III of the Seleucid Empire had signed the non-aggression pact. Although the exact nature of this treaty is unclear, and the exact Roman reason for getting involved despite decades of apathy towards Greece (the relevant passages on this from our primary source, Polybius, have been lost), the Greek delegation was successful.[15] Initially, Rome didn't intend to fight a war against Macedon, but rather to intervene on their behalf diplomatically.[15]

Rome gave Philip an ultimatum that he must cease in his campaigns against Rome's new Greek allies. Doubting Rome's strength (not an unfounded belief given Rome's performance in the First Macedonian War) Philip ignored the request, which surprised the Romans. Believing their honor and reputation on the line, Rome escalated the conflict by sending an army of Romans and Greek allies to force the issue, beginning the Second Macedonian War.[16] Surprisingly (given his recent successes against the Greeks and earlier successes against Rome), Philip's army buckled under the pressure from the Roman-Greek army. Roman troops led by then consul Titus Quinctius Flamininus reached the plain of Thessaly by 198 BC.[17] In 197 BC the Romans decisively defeated Philip at the Battle of Cynoscephalae, and he sued for peace.[18] In the resulting Treaty of Tempea, Philip V was forbidden from interfering with affairs outside his borders, and was required to relinquish his recent Greek conquests. At the Olympiad in 196 BC Rome proclaimed the "Freedom of the Greeks", which constituted Rome's (arguably misguided) new policy towards Greece. This was that Greece was now stable and Rome could completely remove itself from Greek affairs without risking more instability.[19] It seemed that Rome had no further interest in the region, as they withdrew all military forces without even attempting to consolidate any gains, and subsequently returned to their prior apathy even when their Greek allies ignored later Roman requests.[19]

Seleucid War (192 to 188 BC)

With Egypt and Macedonia now weakened, the Seleucid Empire became increasingly aggressive and successful in its attempts to conquer the entire Greek world.[20] When Rome pulled out of Greece at the end of the Second Macedonian War, they (and their allies) thought they had left behind a stable peace. However, by weakening the last remaining check on Seleucid expansion, they left behind the opposite. Now not only did Rome's allies against Philip seek a Roman alliance against the Seleucids, but Philip himself even sought an alliance with Rome.[21] The situation was made worse by the fact that Hannibal was now a chief military advisor to the Seleucid emperor, and the two were believed to be planning for an outright conquest not just of Greece, but of Rome also.[22] The Seleucids were much stronger than the Macedonians had ever been, given that they controlled much of the former Persian Empire, and by this point had almost entirely reassembled Alexander the Great's former empire.[22] Fearing the worst, the Romans began a major mobilization, all but pulling out of recently pacified Spain and Gaul.[22] They even established a major garrison in Sicily in case the Seleucids ever got to Italy.[22] This fear was shared by Rome's Greek allies, who had largely ignored Rome in the years after the Second Macedonian War, but now followed Rome again for the first time since that war.[22] A major Roman-Greek force was mobilized under the command of the great hero of the Second Punic War, Scipio Africanus, and set out for Greece, beginning the Roman-Syrian War. After initial fighting that revealed serious Seleucid weaknesses, the Seleucids tried to turn the Roman strength against them at the Battle of Thermopylae (as they believed the 300 Spartans had done centuries earlier to the mighty Persian Empire).[21] Like the Spartans, the Seleucids lost the battle, and were forced to evacuate Greece.[21] The Romans pursued the Seleucids by crossing the Hellespont, which marked the first time a Roman army had ever entered Asia.[21] The decisive engagement was fought at the Battle of Magnesia, resulting in a complete Roman victory.[21][23] The Seleucids sued for peace, and Rome forced them to give up their recent Greek conquests. Though they still controlled a great deal of territory, this defeat marked the beginning of the end of their empire, as they were to begin facing increasingly aggressive subjects in the east (the Parthians) and the west (the Greeks), as well as Judea in the South. Their empire disintegrated into a rump over the course of the next century, when it was eclipsed by Pontus. Following Magnesia, Rome pulled out of Greece again, assuming (or hoping) that the lack of a major Greek power would ensure a stable peace, though it did the opposite.[24]

Third Macedonian War (172 to 168 BC)

Upon Philip's death in Macedon (179 BC), his son, Perseus of Macedon, attempted to restore Macedon's international influence, and moved aggressively against his neighbors.[25] When Perseus was implicated in an assassination plot against an ally of Rome, the Senate declared the third Macedonian War. Initially, Rome did not fare well against the Macedonian forces, but in 168 BC, Roman legions smashed the Macedonian phalanx at the Battle of Pydna.[26] Convinced now that the Greeks (and therefore the rest of the world) would never have peace if Greece was left alone yet again, Rome decided to establish its first permanent foothold in the Greek world. The Kingdom of Macedonia was divided by the Romans into four client republics. Even this proved insufficient to ensure peace, as Macedonian agitation continued.

Fourth Macedonian War (150 to 148 BC)

The Fourth Macedonian War, fought from 150 BC to 148 BC, was fought against a Macedonian pretender to the throne, named Andriscus, who was again destabilizing Greece by attempting to re-establish the old Kingdom.[27] The Romans swiftly defeated the Macedonians at the Second battle of Pydna. In response, the Achaean League in 146 BC mobilized for a new war against Rome. This is sometimes referred to as the Achaean War, and was noted for its short duration and its timing right after the fall of Macedonia. Until this time, Rome had only campaigned in Greece in order to fight Macedonian forts, allies or clients. Rome's military supremacy was well established, having defeated Macedonia and its vaunted Phalanx already on 3 occasions, and defeating superior numbers against the Seleucids in Asia. The Achaean leaders almost certainly knew that this declaration of war against Rome was hopeless, as Rome had triumphed against far stronger and larger opponents, the Roman legion having proved its supremacy over the Macedonian phalanx. Polybius blames the demagogues of the cities of the league for inspiring the population into a suicidal war. Nationalist stirrings and the idea of triumphing against superior odds motivated the league into this rash decision. The Achaean League was swiftly defeated, and, as an object lesson, Rome utterly destroyed the city of Corinth in 146 BC, the same year that Carthage was destroyed.[28] After nearly a century of constant crisis management in Greece, which always led back to internal instability and war when Rome pulled out, Rome decided to divide Macedonia into two new Roman provinces, Achaea and Epirus.

See also

References

- Eckstein, Arthur. "Rome Enters the Greek East". p61

- Eckstein, Arthur. "Rome Enters the Greek East". p62

- Eckstein, Arthur. "Rome Enters the Greek East". p78

- Eckstein, Arthur. "Rome Enters the Greek East". p12

- Eckstein, Arthur. "Rome Enters the Greek East". p40

- Eckstein, Arthur. "Rome Enters the Greek East". p45

- Goldsworthy, In the Name of Rome, p. 36

- Eckstein, Arthur. "Rome Enters the Greek East". p38

- Madden, Thomas. "Empires of Trust". p62

- Madden, Thomas. "Empires of Trust". p64

- Matyszak, The Enemies of Rome, p. 47

- Grant, The History of Rome, p. 115

- Eckstein, Arthur. "Rome Enters the Macedon East". p41

- Eckstein, Arthur. "Rome Enters the Greek East". p42

- Eckstein, Arthur. "Rome Enters the Greek East". p43

- Matyszak, The Enemies of Rome, p. 49

- Boatwright, Mary T. (2012). The Romans: From Village to Empire. New York, New York: Oxford University Press. p. 118. ISBN 978-0-19-973057-5.

- Grant, The History of Rome, p. 117

- Eckstein, Arthur. "Rome Enters the Greek East". p48

- Eckstein, Arthur. "Rome Enters the Greek East". p51

- Grant, The History of Rome, p. 119

- Eckstein, Arthur. "Rome Enters the Greek East". p52

- Lane Fox, The Classical World, p. 326

- Eckstein, Arthur. "Rome Enters the Greek East". p55

- Grant, The History of Rome, p. 120

- Matyszak, The Enemies of Rome, p. 53

- Boatwright, The Romans: From Village to Empire, p. 120

- History of Rome – The republic, Isaac Asimov.

| Library resources about Macedonian Wars |

Further reading

- Erskine, Andrew. 2003. A Companion to the Hellenistic World. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, Ltd.

- Fox, Robin Lane. 2011. Brill's Companion to Ancient Macedon: Studies In the Archaeology and History of Macedon, 650 BC–300 AD. Leiden: Brill.

- Ginouvès, René, and Miltiades B. Hatzopoulos, eds. 1993. Macedonia: From Philip II to the Roman conquest. Translated by David Hardy. Athens, Greece: Ekdotike Athenon.

- Howe, Timothy, Sabine Müller, and Richard Stoneman. 2017. Ancient Historiography On War and Empire. Havertown, PA: Oxbow Books.

- Roisman, Joseph, and Ian Worthington. 2011. A Companion to Ancient Macedonia. Somerset, UK: Wiley.

- Waterfield, Robin. 2014. Taken At the Flood: The Roman Conquest of Greece. New York: Oxford University Press.

- –––. 2018. Creators, Conquerors, and Citizens: A History of Ancient Greece. New York: Oxford University Press.