Mafia

A mafia is a type of organized crime syndicate whose primary activities are protection racketeering, arbitrating disputes between criminals, and brokering and enforcing illegal agreements and transactions.[1] The term "mafia" derives from the Sicilian Mafia. Mafias often engage in secondary activities such as gambling, loan sharking, drug-trafficking, prostitution, and fraud.

The term "mafia" was originally applied only to the Sicilian Mafia and originates in Sicily, but it has since expanded to encompass other organizations of similar methods and purpose, e.g., "the Russian Mafia" or "the Japanese Mafia". The term is applied informally by the press and public; the criminal organizations themselves have their own terms (e.g. the Sicilian Mafia and the related Italian-American Mafia refer to their organizations as "Cosa Nostra"; the "Japanese Mafia" calls itself "Yakuza"; and "Russian Mafia" groups often call themselves "Bratva").

When used alone and without any qualifier, "Mafia" or "the Mafia" typically refers to either the Sicilian Mafia or the American Mafia and sometimes Italian organized crime in general (e.g., Camorra, 'Ndrangheta, Sacra Corona Unita, Stidda, etc.).

Etymology

The word mafia (Italian: [ˈmaːfja]) derives from the Sicilian adjective mafiusu, which, roughly translated, means "swagger", but can also be translated as "boldness" or "bravado". In reference to a man, mafiusu (mafioso in Italian) in 19th century Sicily signified "fearless", "enterprising", and "proud", according to scholar Diego Gambetta.[2] In reference to a woman, however, the feminine-form adjective mafiusa means 'beautiful' or 'attractive'.

Because Sicily was once an Islamic emirate from 831 to 1072, mafia may have come to Sicilian through Arabic, though the word's origins are uncertain. Possible Arabic roots of the word include:

- ma'afi (معفي) = exempted. In Islamic law, Jizya, is the yearly tax imposed on non-Muslims residing in Muslim lands. And people who pay it are "exempted" from prosecution.

- màha = quarry, cave; especially the mafie, the caves in the region of Marsala, which acted as hiding places for persecuted Muslims and later served other types of refugees, in particular Giuseppe Garibaldi's "Redshirts" after their embarkment on Sicily in 1860 in the struggle for Italian unification.[3][4][5][6][7]

- mahyas (مهياص) = aggressive boasting, bragging[5]

- marfud (مرفوض) = rejected, considered to be the most plausible derivation; marfud developed into marpiuni (swindler) to marpiusu and finally mafiusu.[8]

- mu'afa (معافى) = safety, protection[6]

- Ma àfir = the name of an Arab tribe that ruled Palermo.[9][5] The local peasants imitated these Arabs and as a result the tribe's name entered the popular lexicon. The word mafia was then used to refer to the defenders of Palermo during the Sicilian Vespers against rule of the Capetian House of Anjou on 30 March 1282.[10]

- mafyá, meaning "place of shade". The word "shade" meaning refuge or derived from refuge. [11] After the Normans destroyed the Saracen rule in Sicily in the eleventh century, Sicily became feudalistic. Most Arab smallholders became serfs on new estates, with some escaping to "the Mafia." It became a secret refuge.[12]

The public's association of the word with the criminal secret society was perhaps inspired by the 1863 play I mafiusi di la Vicaria ("The Mafiosi of the Vicaria") by Giuseppe Rizzotto and Gaspare Mosca.[13] The words mafia and mafiusi are never mentioned in the play. The play is about a Palermo prison gang with traits similar to the Mafia: a boss, an initiation ritual, and talk of "umirtà" (omertà or code of silence) and "pizzu" (a codeword for extortion money).[14] The play had great success throughout Italy. Soon after, the use of the term "mafia" began appearing in the Italian state's early reports on the phenomenon. The word made its first official appearance in 1865 in a report by the prefect of Palermo Filippo Antonio Gualterio.[15]

Definitions

The term "mafia" was never officially used by Sicilian mafiosi, who prefer to refer to their organization as "Cosa Nostra". Nevertheless, it is typically by comparison to the groups and families that comprise the Sicilian Mafia that other criminal groups are given the label. Giovanni Falcone, an anti-Mafia judge murdered by the Sicilian Mafia in 1992, objected to the conflation of the term "Mafia" with organized crime in general:

While there was a time when people were reluctant to pronounce the word "Mafia" ... nowadays people have gone so far in the opposite direction that it has become an overused term ... I am no longer willing to accept the habit of speaking of the Mafia in descriptive and all-inclusive terms that make it possible to stack up phenomena that are indeed related to the field of organized crime but that have little or nothing in common with the Mafia.[16]

— Giovanni Falcone, 1990

Mafias as private protection firms

Scholars such as Diego Gambetta[17] and Leopoldo Franchetti have characterized the Sicilian Mafia as a "cartel of private protection firms", whose primary business is protection racketeering: they use their fearsome reputation for violence to deter people from swindling, robbing, or competing with those who pay them for protection. For many businessmen in Sicily, they provide an essential service when they cannot rely on the police and judiciary to enforce their contracts and protect their properties from thieves (this is often because they are engaged in black market deals).

The [Sicilian] mafia's principal activities are settling disputes among other criminals, protecting them against each other's cheating, and organizing and overseeing illicit agreements, often involving many agents, such as illicit cartel agreements in otherwise legal industries.

— Diego Gambetta, Codes of the Underworld (2009)

Scholars have observed that many other societies around the world have criminal organizations of their own that provide essentially the same protection service through similar methods. For instance, in Russia after the collapse of Communism, the state security system had all but collapsed, forcing businessmen to hire criminal gangs to enforce their contracts and protect their properties from thieves. These gangs are popularly called "the Russian Mafia" by foreigners, but they prefer to go by the term krysha.

With the [Russian] state in collapse and the security forces overwhelmed and unable to police contract law, [...] cooperating with the criminal culture was the only option. [...] most businessmen had to find themselves a reliable krysha under the leadership of an effective vor.

In his analysis of the Sicilian Mafia, Gambetta provided the following hypothetical scenario to illustrate the Mafia's function in the Sicilian economy. Suppose a grocer wants to buy meat from a butcher without paying sales tax to the government. Because this is a black market deal, neither party can take the other to court if the other cheats. The grocer is afraid that the butcher will sell him rotten meat. The butcher is afraid that the grocer will not pay him. If the butcher and the grocer can't get over their mistrust and refuse to trade, they would both miss out on an opportunity for profit. Their solution is to ask the local mafioso to oversee the transaction, in exchange for a fee proportional to the value of the transaction but below the legal tax. If the butcher cheats the grocer by selling rotten meat, the mafioso will punish the butcher. If the grocer cheats the butcher by not paying on time and in full, the mafioso will punish the grocer. Punishment might take the form of a violent assault or vandalism against property. The grocer and the butcher both fear the mafioso, so each honors their side of the bargain. All three parties profit.

Mafia-type organizations under Italian law

Introduced by Pio La Torre, article 416-bis of the Italian Penal Code defines a Mafia-type association (Associazione di Tipo Mafioso) as one where "those belonging to the association exploit the potential for intimidation which their membership gives them, and the compliance and omertà which membership entails and which lead to the committing of crimes, the direct or indirect assumption of management or control of financial activities, concessions, permissions, enterprises and public services for the purpose of deriving profit or wrongful advantages for themselves or others."[19][20]

International

Mafia-proper can refer to either:

- American Mafia

- Sicilian Mafia (aka "Cosa Nostra")

Italy

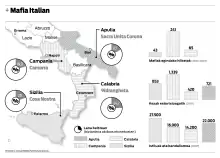

Other Italian criminal organizations include:

- Banda della Comasina, in Lombardy

- Banda della Magliana and Mafia Capitale, in Lazio

- Basilischi, in Basilicata

- Camorra, in Campania

- Mala del Brenta, in Veneto

- 'Ndrangheta, in Calabria[21]

- Sacra Corona Unita, in Apulia

- Stidda, in Sicily

Other countries

References

- Gambetta 2009: "The mafia's principal activities are settling disputes among other criminals, protecting them against each other's cheating, and organizing and overseeing illicit agreements, often involving many agents, such as illicit cartel agreements in otherwise legal industries. Mafia-like groups offer a solution of sorts to the trust problem by playing the role of a government for the underworld and supplying protection to people involved in illegal markets ordeals. They may play that role poorly, sometimes veering toward extortion rather than genuine protection, but they do play it."

- This etymology is based on the books Che cosa è la mafia? by Gaetano Mosca, Mafioso by Gaia Servadio, The Sicilian Mafia by Diego Gambetta, Mafia & Mafiosi by Henner Hess, and Cosa Nostra by John Dickie (see Books below).

- According to Giuseppe Guido Lo Schiavo, "cave" in Arabic literary writing is Maqtaa hagiar, while in popular Arabic it is pronounced as Mahias hagiar and then "from Maqtaa (Mahias) = mafia, that is cave, hence the name (ma)qotai, quarrymen, stone-cutters, that is, mafia." (Loschiavo 1962: 27-30). See: Fabrizio Fioretti (2011), Il termine "mafia", Sveučilište Jurja Dobrile u Puli.

- Mosca, Che cosa è la mafia?, p. 51

- Hess, Mafia & Mafiosi, pp. 1-3

- Gambetta, The Sicilian Mafia, pp. 259-261.

- Coluccello, Challenging the Mafia Mystique, p.3

- Lupo, History of the Mafia, p. 282 quoting Lo Monaco (1990), Lingua nostra.

- John Follain (8 Jun 2009). The Last Godfathers. Hachette UK. ISBN 9781848942493.

Even the origin of the word 'mafia' remains obscure. Some believe its roots lie in the Arab domination of Sicily from 827 to 1061 and the Arabic word mahias (daring) or Ma àfir (the name of a Saracen tribe).

- Richard Lindberg (1 Aug 1998). To Serve and Collect: Chicago Politics and Police Corruption from the Lager Beer Riot to the Summerdale Scandal, 1855-1960 (illustrated ed.). SIU Press. p. 161. ISBN 9780809322237.

The word "Mafia" is a derivative of the Arabic maafir, the name of a tribe of Arabs who settled in Palermo, Sicily before the Middle Ages. The Sicilian peasants adopted the customs of the nomadic tribe, integrating the name into everyday language. When the French were massacred in Palermo on Easter Sunday, 1282, the townsmen described their brave defenders as the "Mafia." In 1417 this secret band of guerrillas absorbed another society of local origin, the Camorra.

- Theroux, Paul (1995). The Pillars of Hercules: A Grand Tour of the Mediterranean. New York: Fawcett Columbine. p. 176. ISBN 0449910857.

- Lewis, Norman (1964). The Honoured Society.

- "Sicily And The Mafia". americanmafia.com. February 2004.

- Gambetta, The Sicilian Mafia, p. 136.

- Lupo, The History of the Mafia Archived 2013-01-06 at the Wayback Machine, p. 3.

- Lupo, History of the Mafia, pp. 1–2

- Diego Gambetta (1993). The Sicilian Mafia: The Business of Private Protection

- Glenny 2008

- Seindal, Mafia: money and politics in Sicily, p. 20

- Art. 416-bis, Codice Penale - Associazione di Tipo mafioso

- Il senatore Carlo Giovanardi difendeva un'azienda di amici che era colpita da interdittiva antimafia, L'Espresso, 4 maggio 2017

Sources

- Albanese, Jay S., Das, Dilip K. & Verma, Arvind (2003). Organized Crime: World Perspectives. Prentice Hall. ISBN 9780130481993

- Coluccello, Rino (2016). Challenging the Mafia Mystique: Cosa Nostra from Legitimisation to Denunciation, Palgrave Macmillan, ISBN 978-1-349-55552-9

- Dickie, John (2007). Cosa Nostra: A History of the Sicilian Mafia. Hodder. ISBN 978-0-340-93526-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gambetta, Diego (1993). The Sicilian Mafia: The Business of Private Protection. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-674-80742-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gambetta, Diego (2009). Codes of the Underworld: How Criminals Communicate. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691119373.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Glenny, Misha (2008). McMafia. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1400095124.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hess, Henner (1998). Mafia & Mafiosi: Origin, Power and Myth. London: Hurst & Co Publishers. ISBN 1-85065-500-6

- (in Italian) Lo Schiavo, Giuseppe Guido (1964), Cento anni di mafia, Rome: Vito Bianco Editore

- Lupo, Salvatore (2009), The History of the Mafia, New York: Columbia University Press, ISBN 978-0-231-13134-6

- (in Italian) Mosca, Gaetano (1901/2015). Che cosa è la mafia?, Messina: Il Grano, ISBN 978-88-99045-11-1 (See Full text in Italian and the English translation for a background on the publication)

- Mosca, Gaetano (1901/2014). "What is Mafia", M&J, 2014. Translation of the book "Che cosa è la Mafia", Giornale degli Economisti, July 1901, pp. 236–62. ISBN 979-11-85666-00-6

- Paoli, Letizia (2003). Mafia Brotherhoods: Organized Crime, Italian Style. Oxford/New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-515724-9

- Seindal, René (1998). Mafia: Money and Politics in Sicily, 1950-1997. Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press. ISBN 87-7289-455-5

- Servadio, Gaia (1976). Mafioso: a history of the Mafia from its origins to the present day. London: Secker & Warburg. ISBN 0-436-44700-2

- Wang, Peng (2017). The Chinese Mafia: Organized Crime, Corruption, and Extra-Legal Protection. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198758402