Mahanoy Area School District v. B.L.

Mahanoy Area School District v. B.L. is an ongoing lawsuit that will be heard in 2021 by the Supreme Court of the United States. The case involves the freedom of speech rights of a student under the First Amendment to the United States Constitution for speech made on social media outside of school grounds, challenging past interpretation of Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District and Bethel School District v. Fraser in light of online communications.

| Mahanoy Area School District v. B.L. | |

|---|---|

| |

| Full case name | Mahanoy Area School District v. B.L., A Minor, By And Through Her Father Lawrence Levy And Her Mother Betty Lou Levy |

| Docket no. | 20-255 |

| Case history | |

| Prior |

|

The case arose after a student at Mahanoy Area High School in Mahanoy City, Pennsylvania, posted an angry, profane Snapchat message upon learning near the end of the 2016–17 school year that she had not earned a place on the school's varsity cheerleading squad for the next season. A screenshot of the self-deleting message was saved and seen by school officials, who suspended the student from cheerleading for the next year, on the grounds that she had signed and was subject to a school district policy prohibiting such speech on social media. Her parents filed suit on her behalf in federal court, arguing that the district had unconstitutionally punished her for speech made completely outside of the school that did not pose a risk of disruption.

Under Tinker, student speech on campus is protected by the First Amendment so long as it does not disrupt school operations. Fraser carved out an exception for speech that, while not disruptive, was vulgar or sexually suggestive; another case, Morse v. Frederick, allowed schools to punish speech that advocated illegal drug use and took place at school-sponsored events off-campus. Since the rise of the Internet and social media, courts have been dealing with cases brought by students who, like B.L., made online statements off-campus that led to school discipline. Until her case, none had reached the Supreme Court.

The Middle District of Pennsylvania held in B.L.'s favor, ruling that her Snap had had no connection to the school and therefore was beyond its disciplinary reach under Tinker.[1] On the district's appeal to the Third Circuit, a panel not only affirmed the lower court but held that Tinker could not be read, as other appellate circuits had, to apply to any off-campus speech, creating a circuit split for the Supreme Court to resolve. A dissenting judge agreed with B.L. that the school had overstepped its constitutional authority, but disagreed with his colleagues on whether the case required reassessing Tinker.[2]

Underlying dispute

B.L. was a ninth-grade student and junior varsity (JV) cheerleader at Mahanoy Area High School, a public secondary school operated by the Mahanoy Area School District, covering the area in and around Mahanoy City in Schuylkill County, Pennsylvania.[3] In addition to cheering at football, basketball and wrestling matches, her obligations as a cheerleader included raising additional funding for the squad from the community.[4] As a condition of being a cheerleader, she was required to sign a code of conduct that required squad members show respect for their teammates, coaches, the school, teachers, other schools' cheerleaders; the rule forbade the use of profanity. Another rule forbade cheerleaders from posting "negative information" about "cheerleading, cheerleaders or coaches" on the Internet.[5] The code had been written by previous cheerleading coaches and approved by the school board.[6]

Near the end of the 2016–17 academic year, B.L. tried out for the next year's cheerleading squad. She hoped to make the varsity, but the two coaches, both teachers in the district, again found her only good enough for the JV squad. An eighth-grader at the tryouts, meanwhile, made the varsity.[5]

The following weekend, B.L. and a friend commiserated about the apparent unfairness of this at the Cocoa Hut, a convenience store in downtown Mahanoy City where students often socialized. Using B.L.'s smartphone, the two took a picture of themselves of the two with middle fingers raised and posted it to her Snapchat story with the text "fuck school fuck softball fuck cheer fuck everything".[7][8][9] A followup Snap expressed their frustration about being kept on the JV squad while the incoming freshman girl made varsity; they believed they were being treated unfairly. B.L. sent the two Snaps to a group of 250 friends, many of whom were fellow students, some of them cheerleaders themselves.[5]

The Snap itself self-deleted in a short period of time, but one of her teammates took a screenshot.[7] One of those teammates was the daughter of one of the coaches, who had herself been suspended from cheering at a few games after she had posted disparaging remarks online about another school's cheerleading squad's uniforms.[10] By the time school resumed for the following week, the screenshot had been widely shared among students, especially the cheerleaders. Some who had seen it came to the cheerleading coaches "visibly upset" by the Snap[11] over the next few days.[5] At the end of the week one of the coaches pulled B.L. out of class to inform her that she was suspended from cheerleading for the next year as a result of her Snap.[4] B.L.'s parents appealed the suspension to the school board, which upheld it.[8]

Prior Supreme Court jurisprudence on student speech

In 1943's West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette, the U.S. Supreme Court first considered the First Amendment rights of students in public schools. Six justices held that students could not be required to say the Pledge of Allegiance or salute the flag, which they had refused to do as Jehovah's Witnesses.[12] A quarter-century later it first considered what rights students had to express themselves in school. In Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District[13] the first of four cases it has heard on the subject, it held that they did, but has limited that right in two of the three cases since then.[14][15] In the third it limited student freedom of the press.[16]

Five students who wore black armbands to school in 1965 as a protest against the Vietnam War were suspended after defying an administrative edict forbidding doing so; they challenged their punishment in federal court.[13] "It can hardly be argued that either students or teachers shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate", Justice Abe Fortas wrote for the majority in Tinker, [17] now considered the seminal case in school speech jurisprudence.[18][19]

The Tinker Court had taken note of the silent, passive nature of the armband protest, observing that possible disruption to the schools' operations feared by administrators had not actually occurred. That was not the case in Bethel School District v. Fraser, a 1986 case in which the court sided with the administration in upholding its disciplinary actions against a student who gave a speech at an assembly in support of a candidate for student office laced with double entendres and sexual innuendo. "The First Amendment does not prevent the school officials from determining that to permit a vulgar and lewd speech such as respondent's would undermine the school's basic educational mission", Chief Justice Warren Burger wrote for a 7–2 majority. "A high school assembly or classroom is no place for a sexually explicit monologue directed towards an unsuspecting audience of teenage students."[14]

Two years later, in Hazelwood School District v. Kuhlmeier, the Court upheld administrators' decision to remove articles whose subject matter they had considered inappropriate for a student audience from a newspaper produced by journalism students. "[S]tudents, parents, and members of the public might reasonably perceive [them] to bear the imprimatur of the school" since they had been produced as part of a class, wrote Justice Byron White for a 6–3 majority. "A school must be able to set high standards for the student speech that is disseminated under its auspices".[16]

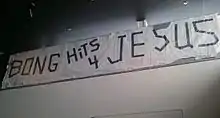

The respondent student in 2007's Morse v. Frederick took the "schoolhouse gate" language from Tinker literally, arguing that the school had unconstitutionally disciplined him for displaying a banner with "BONG HiTS 4 JESUS" written on it from the sidewalk across from the high school he attended. The Court rejected that argument, noting that he had been at a school-sponsored event where students gathered on either side of the street, with teachers and other staff supervising and the band and cheerleaders performing as the Olympic torch relay passed the school. The majority agreed with the school that this mattered more than him not being on school property at the time, holding the student's suspension was permissible under Tinker.[20]

Lower courts

B.L., represented through her parents and supported by the American Civil Liberties Union, sued the school in federal court for the Middle District of Pennsylvania; her attorney emphasized that her remarks were those of frustration made on her own social media account on her own time and contained neither threats nor any mention of the name of her school.[8] In October 2017, four months after B.L. was suspended from cheerleading, Judge A. Richard Caputo granted her a preliminary injunction forbidding the school from enforcing the suspension.[3] He held that B.L. was likely to succeed on the merits of her case and would suffer irreparable harm without the injunction. "Simply put, the ability of a school to punish lewd or profane speech disappears once a student exits school grounds."[21]

In March 2019, Caputo granted summary judgement for B.L.,[1] as the school could not curb B.L.'s off-campus speech per Fraser and that the speech did not disrupt the school's operation under Tinker.[8] He rejected the district's arguments that B.L. had waived her constitutional rights by joining the cheerleading squad based on previous case law, that it could not be liable for the coaches' actions since it had approved the code B.L. had signed, and that she had no constitutional right to be a cheerleader since it was irrelevant whether she did or not. "The District's concession that B.L.'s speech occurred off-campus is all but fatal", he said, finding that Tinker and Fraser's exceptions did not apply as her speech was neither disruptive nor on-campus respectively; he found it more similar to the mock MySpace profile at issue in J.S.. Caputo allowed that there were some other cases which allowed schools to impose greater speech limits on student-athletes, but those did not come into play since B.L. was not engaging in school-sponsored speech.[22]

Appeal

The school district appealed to the Third Circuit. A three-judge panel acknowledged that "B.L.'s snap was crude, rude, and juvenile, just as we might expect of an adolescent",[7] but upheld the District Court's holding in her favor, again finding that both Tinker and Fraser did not support restricting her off-campus speech.[8] Writing for the panel, Judge Cheryl Ann Krause, agreed with Caputo that the speech had clearly been off-campus, thus punishing B.L. for it violated her First Amendment rights.[2]

Krause and the panel went further and reviewed the other circuits' approaches to the on-/off-campus distinction. While she agreed this was a difficult question to resolve, and commended their efforts, "we find their approaches unsatisfying in three respects."[23]

The Second Circuit had erred in applying the reasoning from Wisniewski, where a student's threatening action posed an undeniable foreseeability of disruption, to Doninger: 'What began as a narrow accommodation of unusually strong interests on the school's side ... became a broad rule governing all off-campus expression." The other circuits, Krause wrote, "have adopted tests that sweep far too much speech into the realm of schools' authority", especially given the reach of modern communications technology. "Implicit in the reasonable foreseeability test, therefore, is the assumption that the internet and social media have expanded Tinker's schoolhouse gate to encompass the public square." The nexus test the Fourth Circuit had used in Kowalski collapsed the analysis in a way she called "tautological ... Schools can regulate off-campus speech under Tinker when the speech would satisfy Tinker."[23]

Lastly, Krause found that whether they had crafted tests or not, the other circuits' approaches lacked "clarity and predictability." The Second and Eighth Circuits' foreseeability test, used in Wisniewski and S.J.W., "ha[s] made it difficult for students speaking off campus to predict when they enjoy full or limited free speech rights. After all, a student can control how and where she speaks but exercises little to no control over how her speech may 'come to the attention of the school authorities'". It was likewise difficult for students using the Fourth Circuit's nexus test, articulated in Kowalski, to ascertain when their speech off-campus might implicate the school's "pedagogical mission".[23]

Instead, Krause built on the approach Smith had taken in J.S. and held that Tinker did not apply to off-campus speech, which she defined as "speech that is outside school-owned, -operated, or -supervised channels and that is not reasonably interpreted as bearing the school's imprimatur." This holding would be clear and easy to understand, she wrote. As for threatening or harassing speech, which was not at issue in the instant case, it "would no doubt raise different concerns and require consideration of other lines of First Amendment law."[24]

Judge Thomas L. Ambro concurred in the judgement, agreeing that B.L.'s free-speech rights had been violated but dissented from the majority's holding that this was because Tinker forbade any regulation of off-campus speech, a question B.L. had said the court need not decide.[25][7]

The school district petitioned to the Supreme Court to take the case, arguing that particularly with the COVID-19 pandemic, the nature of online communications required reevaluation of the distinction between on versus off-campus speech in the context of distance learning.[8] The Supreme Court granted certiorari to resolve the circuit split (as the Fifth Circuit's decision in Bell had held that Tinker does govern off-campus student speech) in January 2021, with oral arguments expected to be heard sometime later that term.[26]

See also

- List of United States Supreme Court cases involving the First Amendment

- Cohen v. California, another free-speech case involving the use of fuck

Notes

References

- B.L. v. Mahanoy Area Sch. Dist., 376 F. Supp. 3d 429 (M.D. Pa. 2019) ("Mahanoy II").

- B.L. v. Mahanoy Area Sch. Dist., 964 F.3d 170 (3d Cir. 2020) ("Mahanoy III").

- B.L. v. Mahanoy Area Sch. Dist., 289 F. Supp. 3d 607 (M.D. Pa. 2017) ("Mahanoy I").

- Mahanoy I, 289 F. Supp. 3d at 610.

- Mahanoy II, 376 F. Supp. 3d at 432–33.

- Mahanoy II, 376 F. Supp. 3d at 438.

- Walsh, Mark (July 1, 2020). "Federal Appeals Court Rejects Student Discipline for Vulgar Off-Campus Message". EducationWeek.

- Liptak, Adam (December 28, 2020). "A Cheerleader's Vulgar Message Prompts a First Amendment Showdown". The New York Times. The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 3, 2020. Retrieved January 4, 2021.

- Weiss, Debra Cassens (January 11, 2021). "Supreme Court agrees to hear First Amendment case of suspended cheerleader". ABA Journal.

- Mahanoy II, 376 F. Supp. 3d at 444.

- Mahanoy III, 964 F.3d at 175–76.

- West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette, 319 U.S. 624 (1943)

- Tinker v. Des Moines Indep. Cmty. Sch. Dist., 393 U.S. 503 (1969).

- Bethel Sch. Dist. v. Fraser, 478 U.S. 675, 685 (1986).

- Morse v. Frederick, 551 U.S. 393 (2007).

- Hazelwood Sch. Dist. v. Kuhlmeier, 484 U.S. 260, 272 (1988).

- Tinker, 393 U.S. at 506.

- Katherine A. Ferry, Reviewing the Impact of the Supreme Court's Interpretation of 'Social Media' as Applied to Off-Campus Student Speech, 49 Loy. U. Chi. L.J. 717, 723 (2019).

- Julie Barnard, Shen v. Albany Unified School District: An Articulation of the Boundaries of Student Speech in the Social Media Era, 21 Tul. J. Tech. & Intell. Prop. 131, 132 (2019).

- Morse, 551 U.S. at 397–98.

- Mahanoy I, 289 F. Supp. 3d at 613.

- Mahanoy II, 376 F. Supp. 3d at 437–43.

- Mahanoy III, 964 F.3d at 187–88.

- Mahanoy III, 964 F.3d at 190–91.

- Mahanoy III, 964 F.3d at 194–96.

- Robinson, Kimberly Strawbridge (January 8, 2021). "U.S. Supreme Court Takes Up Cheerleader Free Speech Dispute". Bloomberg News. Retrieved January 8, 2021.