Manapouri Power Station

Manapōuri Power Station is an underground hydroelectric power station on the western arm of Lake Manapouri in Fiordland National Park, in the South Island of New Zealand. At 850 MW installed capacity (although limited to 800 MW due to resource consent limits[3]), it is the largest hydroelectric power station in New Zealand, and the second largest power station in New Zealand. The station is noted for the controversy and environmental protests by the Save Manapouri Campaign against the raising the level of Lake Manapouri to increase the station's hydraulic head, which galvanised New Zealanders and were one of the foundations of the New Zealand environmental movement.

| Manapōuri Power Station | |

|---|---|

The Manapōuri Power Station machine hall | |

Location of Manapōuri Power Station in New Zealand | |

| Country | New Zealand |

| Location | west end of Lake Manapōuri, Fiordland National Park, Southland |

| Coordinates | 45°31′17″S 167°16′40″E |

| Status | Operational |

| Construction began | February 1964[1] |

| Opening date | September 1971[1] |

| Construction cost | NZ$135.5 million (original station) NZ$200 million (second tailrace tunnel) NZ$100 million (half-life refurbishment) [1] |

| Owner(s) | Meridian Energy |

| Reservoir | |

| Creates | Lake Manapōurib |

| Catchment area | 3,302 km2 (1,275 sq mi)[1] |

| Surface area | 141.6 km2 (54.7 sq mi)[1] |

| Maximum water depth | 444 m (1,457 ft) |

| Manapōuri Power Station | |

| Type | Conventional |

| Turbines | 7× vertical Francis[1] |

| Installed capacity | 850 MW[1] |

| Capacity factor | 68.4% / 79.7%c |

| Annual generation | 5100 GWh[2] |

| b Lake Manapōuri is a natural lake - the drop between it and the sea is used by Manapōuri station. ^c The former figure is based on the installed capacity of 850 MW, while the latter figure is based on the resource consent limited capacity of 800 MW | |

Completed in 1971, Manapōuri was built to supply electricity to the Tiwai Point aluminium smelter near Bluff, some 160 km (99 mi) to the southeast. Later, it was also connected into the South Island transmission network. The station utilises the 230-metre (750 ft) drop between the western arm of Lake Manapouri and the Deep Cove branch of the Doubtful Sound 10 km (6.2 mi) away to generate electricity. The construction of the station required the excavation of almost 1.4 million tonnes of hard rock to build the machine hall and a 10 km tailrace tunnel, with a second parallel tailrace tunnel completed in 2002 to increase the station's capacity.

Since April 1999, the power station has been owned and operated by state-owned electricity generator Meridian Energy.

Construction

The power station machine hall was excavated from solid granite rock 200 metres below the level of Lake Manapōuri. Two tailrace tunnels take the water that passes through the power station to Deep Cove, a branch of Doubtful Sound, 10 kilometres (6.2 mi) away.

Access to the power station is via a two-kilometre vehicle-access tunnel which spirals down from the surface, or a lift that drops 193 metres (633 ft) down from the control room above the lake. There is no road access into the site; a regular boat service ferries power station workers in 35 km across the lake from Pearl Harbour, located in the town of Manapouri at the southeast corner of the lake.

This same access was for many years used to ferry tourists for public tours of the site, but since 2018 maintenance work by Meridian Energy means tours are closed "for an indefinite period".[4]

The original construction of the power station cost NZ$135.5 million (NZ$2.15 billion in 2013 dollars),[5][6] involved almost 8 million man hours to construct, and claimed the lives of 16 workers.[1]

Soon after the power station began generating at full capacity in 1972, engineers confirmed a design problem. Greater than anticipated friction between the water and the tailrace tunnel walls meant reduced hydrodynamic head. For 30 years, until 2002, station operators risked flooding the powerhouse if they ran the station at an output greater than 585 megawatts (784,000 hp) (with high lake level and a low tide the station could generate up to 603 megawatts (809,000 hp)), far short of the designed peak capacity of 700 megawatts (940,000 hp). Construction of a second tailrace tunnel in the late 1990s, 10-kilometre (6.2 mi) long and 10 metres in diameter, finally solved the problem and increased capacity to 850 megawatts (1,140,000 hp). The increased exit flow also increased the effective head, allowing the turbines to generate more power without using more water.

History

Early history

The first surveyors mapping out this corner of New Zealand noted the potential for hydro generation in the 178-metre drop from the lake to the Tasman Sea at Doubtful Sound. The idea of building a power station was first formulated by Peter Hay, the Superintending Engineer of the Public Works Department, and Lemuel Morris Hancock, the Electrical Engineer and General Superintendent of the Transmission Department of the California Gas and Electric Company during their November 1903 inspection of Lakes Manapōuri and Te Anau. Each of the 1904 reports by Hay and Hancock noted the hydraulic potential of the lake systems, being so high above sea level, and while the rugged isolation of the region meant that it would be neither practical nor economic to generate power for domestic consumption, the engineers realised that the location and scale of the project made it uniquely suited to electro-industrial developments such as electro-chemical or electro-metallurgical production.

In January 1926, a Wellington-based syndicate of ten businessmen headed by Joseph Orchiston and Arthur Leigh Hunt, New Zealand Sounds Hydro-Electric Concessions Limited, was granted by the government via an Order in Council the rights to develop the waters which discharged into Deep Cove, Doubtful Sound, and the waters of Lake Manapōuri, to generate in total some 300,000 horsepower (220,000 kW). The company attempted to attract Australian, British and American finance to develop the project, which would have required the construction of a powerhouse and factory complex in Deep Cove, with accommodation for an estimated 2,000 workers and wharf facilities, with the complex producing atmospheric nitrogen in the form of fertiliser and munitions. Various attempts to finance the scheme were not successful, with the water rights lapsing and the company fading into obscurity by the 1950s.

In 1955 the modern history of Manapōuri starts, when Harry Evans, a New Zealand geologist with Consolidated Zinc Proprietary Ltd identified a commercial deposit of bauxite in Australia on the west coast of Cape York Peninsula, near Weipa. It turned out to be the largest deposit of bauxite in the world yet discovered. In 1956 The Commonwealth Aluminium Corporation Pty Ltd, later known as Comalco, was formed to develop the bauxite deposits. The company started investigating sources of large quantities of cheap electricity needed to reduce the alumina recovered from the bauxite into aluminium. Comalco settled on Manapōuri as that source of power and Bluff as the site of the smelter. The plan was to refine the bauxite to alumina in Queensland, ship the alumina to New Zealand for smelting into metal, then ship it away to market.

Construction history

- February 1963, Bechtel Pacific Corporation won the design and supervision contract.

- July 1963, Utah Construction and Mining Company and two local firms won contracts to construct the tailrace tunnel and Wilmot Pass road. Utah Construction also won the powerhouse contract.

- August 1963, Wanganella, a former passenger liner, was moored in Doubtful Sound to be used as a hostel for workers building the tailrace tunnel. During the 1930s she was a top-rated trans-Tasman passenger liner, with accommodation for 304 first-class passengers. She continued to serve as a hostel until December 1969.

- February 1964, tailrace-tunnel construction began.

- December 1967, powerhouse construction was completed.

- October 1968, tunnel breakthrough.

- 14 September 1969, the first water flowed through the power station.

- September/October 1969, commissioning of the first four generators.

- August/September 1971, the remaining three generators were commissioned.

- 1972, the station was commissioned. It was then that engineers confirmed the limitations of peak capacity due to excess friction in the tailrace tunnel.

- June 1997, construction work by a Dillingham Construction / Fletcher Construction / Ilbau joint venture began on the second tailrace tunnel.

- 1998, the Robbins tunnel boring machine starts drilling at the Deep Cove end of the tunnel.

- 2001, tunnel breakthrough.

- 2002, the second tunnel was commissioned. A $98 million mid-life refurbishment of the seven generating units begins, with the goal of raising their eventual output to 135 MVA (121.5 MW) each. By June 2006, four generating units had been upgraded, and the project was on schedule for completion in August 2007.[7] By the end of 2007, all seven turbines had been upgraded.[8]

- 2014, three transformers were replaced following the discovery of an issue with the oil cooler on one of Manapōuri's seven transformers during maintenance in March. The first removed transformer was the largest pieces of hardware to leave the station since its completion. The three transformers were replaced with newly manufactured ones, delivered via Wilmot Pass between December 2014 and February 2015.[9]

Political history

In July 1956, the New Zealand Electricity Department announced the possibility of a project using the Manapōuri water, an underground power station and underground tailrace tunnel discharging the water at Deep Cove in Doubtful Sound. Five months later, Consolidated Zinc Proprietary Limited (later known as Comalco) formally approached the New Zealand government about acquiring a large amount of electricity for aluminium smelting.

On 2 May 1961 Stan Goosman for the Ministry of Works for the First National Government, signed an agreement making it binding on any future government for this project to go ahead,[10] On 19 January 1960, the Labour Government and Consolidated Zinc/Comalco signed a formal agreement for Consolidated Zinc to build both an aluminium smelter at Tiwai Point and a power station in Manapōuri. The agreement violated the National Parks Act, which provided for formal protection of the Park, and required subsequent legislation to validate the development. Consolidated Zinc/Comalco received exclusive rights to the waters of both Lakes Manapōuri and Te Anau for 99 years. Consolidated Zinc/Comalco planned to build dams that would raise Lake Manapōuri by 30 metres (98 ft), and merge the two lakes. The Save Manapouri Campaign was born, marking the beginning of the modern New Zealand environmental movement.

In 1963, Consolidated Zinc/Comalco decided it could not afford to build the power station. The New Zealand government took over. Electricity generated by the plant was sold to Consolidated Zinc/Comalco at basement prices, with no provision for inflation.

In 1969, Consolidated Zinc's electric power rights were transferred to Comalco Power (NZ) Ltd, a subsidiary of the Australian-based Comalco Industries Pty Ltd.

In 1970, the Save Manapouri Campaign organised a petition to Parliament opposing raising the water level of Lake Manapōuri. The petition attracted 264,907 signatures, equivalent to nearly 10 percent of New Zealand's population at the time.

In 1972, New Zealand elected a new Labour government. In 1973, the Prime Minister, Norman Kirk, honoured his party’s election pledge not to raise the levels of the lakes. He created an independent body, the Guardians of Lake Manapōuri, Monowai, and Te Anau, to oversee management of the lake levels. The original six Guardians were all prominent leaders of the Save Manapouri Campaign.

In 1984, the Labour Party returned to power in the general election. The resulting period was tumultuous, with Labour's controversial ministers Roger Douglas and Richard Prebble driving rogernomics, a rapid introduction of "free market" reforms and privatisation of government assets. Many suspected the Manapōuri Power station would be sold, and Comalco was the obvious buyer. In 1991, the Save Manapouri Campaign was revived, with many of the same leaders and renamed Power For Our Future. The Campaign opposed selling off the power station to ensure that Comalco did not rehabilitate its plans to raise Lake Manapouri's waters. The Campaign was successful. The government announced that Manapōuri would not be sold to Comalco.

On 1 April 1999 - the 1998 reform of the New Zealand electricity sector took effect: the Electricity Corporation of New Zealand was broken up and Manapōuri was transferred to new state-owned generator Meridian Energy.

In July 2020, Rio Tinto announced that they would be closing the aluminium smelter in Bluff in August 2021,[11][12] triggering discussions on how to utilize the energy generated in Manapouri.[13]

Specifications and statistics

Power station

| Average annual energy output | 4800 GW·h |

| Station generating output | 850 MW |

| Number of generating units | 7 |

| Net head | 166 m |

| Maximum tailrace discharge | 510 m³/s |

| Turbines | 7 × vertical Francis type, 250 rpm, 121.5 MW made by General Electric Canada International Inc. |

| Generators | 7 × 13.8 kV, 121.5 MW / 135 MVA (5648 A), made by Siemens Aktiengesellschaft (Germany). |

| Transformers | 8 × 13.8 kV/220 kV, rated at 135 MVA, made by Savigliano (Italy) 1 Transformer is kept as a spare unit.. |

Civil engineering

| Machine hall | 111 m length, 18 m width, 34 m height |

| First tailrace tunnel | 9817 m, 9.2 m diameter |

| Second tailrace tunnel | 9829 m, 10.05 m diameter |

| Road access tunnel | 2,042 m, 6.7 m wide |

| Cable shafts | 7 × 1.83 m diameter, 239 m deep. |

| Lift shaft | 193 m |

| Penstocks | 7 × 180 m long |

Operation

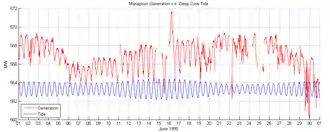

The massive inertia of the column of water in the long tailrace tunnel makes rapid changes to Manapōuri's generation difficult. Further, because the tailrace tunnel emerges at sea level in Deep Cove, power production can be influenced by the state of the tide there. The maximum tidal range is 2·3 metres (7'8") which is a little over one percent of the station's head. The plot shows a variation of about 5MW linked not to the usual twenty-four-hour cycle of electricity usage but to the times of high and low tide, which cycle around the clock.

Transmission

Manapōuri is connected to the rest of the National Grid via two double-circuit 220 kV transmission lines. One line connects Manapōuri to Tiwai Point via North Makarewa substation, north of Invercargill, while the other line connects Manapōuri to Invercargill substation, with one circuit also connecting to North Makarewa substation. Another double-circuit 220 kV line connects Invercargill to Tiwai Point.[14]

References

Bibliography

- Fox, Aaron P.,The Power Game: the development of the Manapouri-Tiwai Point electro-industrial complex, 1904-1969 PhD Thesis, University of Otago, Dunedin, (2001) http://otago.ourarchive.ac.nz/handle/10523/335

- Peat, Neville. Manapouri Saved!: New Zealand’s first great conservation success story: integrating nature conservation with hydro-electric development of Lakes Manapouri and Te Anau, Fiordland National Park Longacre Press, Dunedin (1994)

- Integrating Nature Conservation with Hydro-Electric Development: Conflict Resolution with Lakes Manapouri and Te Anau, Fiordland National Park, New Zealand - Mark, Alan; professor, environmentalist, member of the 'Guardians of Lake Manapouri' institution

- Manapouri - the Toughest Tunnel, a 60-minute television documentary made in 2002 by NHNZ

Notes

- "Manapouri Facts and Figures - Meridian Energy". Retrieved 4 September 2011.

- "List of Generating Stations November 2010 - New Zealand Electricity Authority". Archived from the original on 2011-07-24. Retrieved 2011-01-25.

- "Energy Data File". Ministry of Economic Development. 1 July 2010.

- "Manapouri Underground Power Station". Retrieved 5 August 2019.

- "New Zealand CPI Inflation Calculator - Reserve Bank on New Zealand". Archived from the original on 1 July 2010. Retrieved 25 November 2013.

- "Power From Manapouri - Construction Brochure". Retrieved 30 September 2016.

- "Annual Report 2006" (PDF). Meridian Energy. June 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-10-16. Retrieved 2007-10-04.

- "Refurbishment: Upgrading Turbines at Manapouri". 7 Jan 2008. Retrieved 2016-11-07.

- Brittany Pickett (23 December 2014). "New transformers for Manapouri station". The Southland Times. Retrieved 2016-11-07.

- http://www.legislation.govt.nz/act/public/1963/0023/latest/DLM348259.html

- Rutherford, Hamish (9 July 2020). "Rio Tinto announces plans to close New Zealand aluminium smelter in 2021". NZ Herald. Retrieved 2020-08-20.

- Braae, Alex (10 July 2020). "The Bulletin: Tiwai Point closing affects everything". The Spinoff. Retrieved 2020-08-20.

- "Ambitious proposals for surplus electricity once Tiwai closes". Radio New Zealand. 10 August 2020. Retrieved 2020-08-20.

- "Otago-Southland Regional Plan - 2012 Annual Planning Report" (PDF). Transpower New Zealand Limited. Retrieved 1 January 2011.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Manapouri Power Station. |

- Power station info page from Meridian Energy