Maragheh

Maragheh (Persian: مراغه, Azerbaijani: ماراغا), also Romanized as Marāgheh; also known as Marāgha),[3] is an ancient city and capital of Maragheh County, East Azerbaijan Province, Iran.

Maragheh

ماراغا مراغه | |

|---|---|

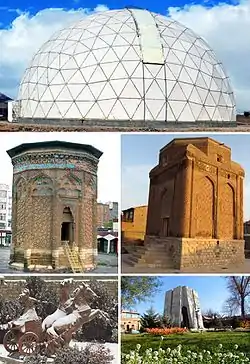

City | |

Top:Maragha Observatory, Middle left:The tomb of Gunbad-Kabud, Middle right:Qyrmyzy Gvnbz, Bottom left:Statue of Anahita, Bottom right:The tomb of Awhaduddin Awhadi | |

Maragheh | |

| Coordinates: 37°23′21″N 46°14′15″E | |

| Country | |

| Province | East Azerbaijan |

| County | Maragheh |

| Bakhsh | Central |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Mohamadreza Ahmadi[1] |

| • Parliament | Hosseinzadeh |

| Population (2016 Census) | |

| • Urban | 175,255 [2] |

| Time zone | UTC+3:30 (IRST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+4:30 (IRDT) |

| Website | http://www.maraghe.com/ |

Maragheh is on the bank of the river Sufi Chay. The population consists mostly of Iranian Azerbaijanis who speak the Azerbaijani language. It is 130 kilometres (81 mi) from Tabriz, the largest city in northwestern Iran.

History

Maragheh is an ancient city encompassed by a high wall ruined in many places, and has four gates. Two stone bridges in good condition are said to have been constructed during the reign of Hulagu Khan (1256–1265),[4] who made Maragheh the capital of the Ilkhanate. Shortly thereafter it became the seat of the Church of the East Patriarch Mar Yaballaha III.

One of the famous burial towers, the Gonbad-e-Kabud (Blue Tower, 1197), is decorated with decorative patterns resembling Penrose tiles.

The 14th century book Al-Vaghfiya Al-Rashidiya (Rashid's Deeds of Endowment) describes many of the estates in the town, and several of the quanat of the time.[5]

The local stone known throughout Iran as Marageh marble, is a travertine obtained at the village of Dashkasan near Azarshahr about 50 km north-west from Maragheh. It is deposited from water, which bubbles up from a number of springs in the form of horizontal layers, which at first are thin crusts and can easily be broken, but gradually solidify and harden into blocks with a thickness of about 20 cm. It is a singularly beautiful substance, being of pink, greenish, or milk-white color, streaked with reddish copper-colored veins.[4] It is exported and sold worldwide under such names as Azarshar Red or Yellow.

Late Miocene strata near Maragheh have produced rich harvests of vertebrate fossils for European and North American museums. A multi-national team reopened the fossil site in 2008.[6]

Hamdollah Mostowfi of the 13th century mentions the language of Maragheh as "Pahlavi Mughayr" (modified Pahlavi, Pahlavi being the name for Middle Persian).[7][8] The 17th century Ottoman Turkish traveler Evliya Çelebi who traveled to Safavid Iran also states:“The majority of the women in Maragheh converse in Pahlavi”.[9] According to the Encyclopedia of Islam:[10] "At the present day, the inhabitants speak Adhar Turkish, but in the 14th century they still spoke “arabicized Pahlawi” (Nuzhat al-Qolub: Pahlawi Mu’arrab) which means an Iranian dialect of the north western group."

Geography

The city is situated in a narrow valley running nearly north and south at the eastern extremity of a well-cultivated plain opening towards Lake Urmia, the world's sixth-largest saltwater lake, which lies 30 km to the west. The town is encompassed by a high wall ruined in many places, and has four gates. Maragheh is surrounded by extensive vineyards and orchards, all well watered by canals led from the river, and producing great quantities of fruit. The hills west of the town consist of horizontal strata of sandstone covered with irregular pieces of basalt.[4]

Maragha observatory

On a hill west of the town are the remains of the famous Maragheh observatory called Rasad Khaneh, constructed under the direction the Ilkhanid king, Hülagü Khan for Nasir al-Din al-Tusi.[4] The building, which no doubt served as a citadel as well, enclosed a space of 340 by 135 meters, and the foundations of the walls were 1.3 to 2 meters in thickness.[4] The observatory was constructed in the thirteenth century and was said to house a staff of at least ten astronomers and a librarian who was in charge of the library which allegedly contained over 40,000 books. This observatory was one of the most prestigious during the medieval times in the Islamic Empire during the golden age of Islamic science. The famous astronomer Ibn al-Shatir did much of his work in this observatory.[11]

In 1256 Nasir al-Din al-Tusi came to work at the Maragheh observatory after being attacked by a group of Mongols who came from the east. These Mongols ambushed Iran, crushing everything in their path. Nasir al-Din al-Tusi was located at the Alamut, a castle in the South Caspian province of Qazin, when the Mongols invaded. Hulagu Khan was the leader of the Mongols and grandson of Genghis Khan. He was a fearless leader and warrior who was determined to conquer not only the Alamut, but many other countries across the globe as well. In order to spare his life, Nasir al-Din al-Tusi told Hulagu that he could predict the future if only he had better equipment. Being interested in science, Hulagu believed him and appointed Nasir al-Din al-Tusi as the scientific advisor of the Mongols. Hulagu allowed Nasir al-Din al-Tusi to build an observatory, and Nasir al-Din al-Tusi chose Maragha, Iran. In 1259, the Maragheh observatory began construction, which took a total of three years to complete. Hulagu also put Nasir al-Din al-Tusi in charge of waqfs which were religious endowments. As director of the observatory, Nasir al-Din al-Tusi and his team were able to make fascinating discoveries in astronomy, physics, and mathematics.[12]

Nasir al-Din al-Tusi was the director of the Maragheh observatory, and made many new discoveries while he was there. Such discoveries include the Tusi-couple, a system based on geometry that includes a smaller circle within a larger circle that is twice the diameter of the smaller circle. The rotations of the smaller circle allow a specific point on the circumference to oscillate back and forth in linear motion. The Tusi-couple solved many issues with Ptolemaic's systems over planetary motion. Also, he helped astronomy become more accurate by discovering brand new stars as well as composing a star catalogue with detailed information about each star. Another notable work from Nasir al-Din al-Tusi was an astronomical book that contained detailed notes and observations about the movement of planets. Under Nasir al-Din al-Tusi, scholars from across the Islamic world came to the Maragheh observatory in order to further their studies in math, science, and astronomy. Furthermore, many new instruments were introduced to the observatory, which made him and his team's work a competitor to that of Europe.[13]

The Maragheh observatory eventually had its downfall in the 13th century. The Mongol leader, Hulagu, died in 1265, and Nasir al-Din al-Tusi died in 1274. Nasir al-Din al-Tusi's son became the director of the observatory after his fathers death, however, there weren't enough scholars at the observatory to fund the research that was being conducted. Therefore, the Maragheh observatory became inactive at the beginning of the 14th century. Over time, the observatory began to crumble due to consistent earthquakes and the lack of preservation of the observatory. Furthermore, the contents of the observatory were stolen during Mongol raids which wiped out important documents and books that were contained within the libraries of the observatory.[12]

Universities in Maragheh

- University of Maragheh

- Payam-e Noor University of Maragheh

- Azad University of Maragheh

Famous natives

For a complete list see: Category:People from Maragheh

Mohammad Sa'ed, was a Prime Minister of Iran.

Mohammad Sa'ed, was a Prime Minister of Iran. Bulud Qarachorlu, poet.

Bulud Qarachorlu, poet.

Sister cities and twin towns

References

- http://www.maraghe.com/shahrdari/shahrdar.html

- https://www.amar.org.ir/english

- Maragheh can be found at GEOnet Names Server, at this link, by opening the Advanced Search box, entering "-3074025" in the "Unique Feature Id" form, and clicking on "Search Database".

-

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Marāgha". Encyclopædia Britannica. 17 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 667–668.

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Marāgha". Encyclopædia Britannica. 17 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 667–668. - Ajam, Mohammad. Water clock in Persia 1383. Conference of Qanat in Iran. in Persian.

- "International paleontologists team up for research on fossil-rich Iranian site". Mehrnews.com. Archived from the original on 5 June 2008. Retrieved 18 May 2008.

- "حمدالله مستوفی هم كه در سدههای هفتم و هشتم هجری می زیست، ضمن اشاره به زبان مردم مراغه می نویسد: "زبانشان پهلوی مغیر است مستوفی، حمدالله: "نزهةالقلوب"، به كوشش محمد دبیرسیاقی، انتشارات طهوری، 1336 Mostawafi, Hamdallah. Nozhat al-Qolub. Edit by Muhammad Dabir Sayyaqi. Tahuri publishers, 1957.

- "Azari, the Old Iranian Language of Azerbaijan," Encyclopaedia Iranica, op. cit., Vol. III/2, 1987 by E. Yarshater. External link:

- Source: Mohammad-Amin Riahi . “Molehaazi darbaareyeh Zabaan-I Kohan Azerbaijan”(Some comments on the ancient language of Azerbaijan), ‘Itilia’at Siyasi Magazine, volumes 181–182. ریاحی خویی، محمدامین، «ملاحظاتی دربارهی زبان كهن آذربایجان»: اطلاعات سیاسی - اقتصادی، شمارهی 182–181 Also available at: https://web.archive.org/web/*/http://www.azargoshnasp.net/languages/Azari/26.pdf]

- V.Minorsky, “Margha” in Encyclopaedia of Islam. Edited by: P. Bearman , Th. Bianquis , C.E. Bosworth , E. van Donzel and W.P. Heinrichs. Brill, 2009. Brill Online."At the present day, the inhabitants speak Adhar Turkish, but in the 14th century they still spoke “arabicized Pahlawi” (Nuzhat al-Qolub: Pahlawi Mu’arrab) which means an Iranian dialect of the north western group."

- Lindberg, David C. (1992). The Beginnings of Western Science. United States: The University of Chicago Press. pp. 179–181. ISBN 9780226482057.

- "The Observational Instruments at the Maragha Observatory after AD 1300". ou-primo.hosted.exlibrisgroup.com. Retrieved 2021-01-20.

- "Al-Tusi, Nasir al-Din". Encyclopedia of Color Science and Technology. Retrieved 2021-01-20.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-09-11. Retrieved 2011-03-19.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- gorazde.ba. "NAČELNIK UPRILIČIO PRIJEM ZA GOSTE IZ IRANA". Grad Goražde. Retrieved 5 April 2018.

- E. Makovicky (1992): 800-year-old pentagonal tiling from Maragha, Iran, and the new varieties of aperiodic tiling it inspired. In: I. Hargittai, editor: Fivefold Symmetry, pp. 67–86. World Scientific, Singapore-London

- Peter J. Lu and Paul J. Steinhardt: Decagonal and Quasi-crystalline Tilings in Medieval Islamic Architecture, Science 315 (2007) 1106–1110

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Maraghe. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Maragheh. |

- Official website

- Maragheh in Enc. Britannica

- The Columbia Encyclopedia

- Photography of Gunbad-i-Qabud

- Astronomy and Astrophysics Research Center of Maragha

- Biography of A'bd alqader ibn Ghaibi al Hafiz al Maraghi

- Maragheh photos

- More photos and Information of Maragheh, Tishineh

| Preceded by Urgench |

Capital of Ilkhanate (Persia) 1256–1265 |

Succeeded by Tabriz |