Measure for Measure

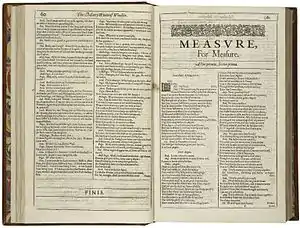

Measure for Measure is a play by William Shakespeare, probably written in 1603 or 1604. Its first recorded performance was in 1604. It was published in the First Folio of 1623.

%252C_as_Vicentio_in_'Measure_for_Measure'_by_William_Shakespeare%252C_1794_British_School_Victoria_and_Albert_Museum.jpg.webp)

The Duke of Vienna steps out from public life. In his place he sets a very respectable and "precise" person. The Duke disguises himself as a friar in order to see if power will corrupt his chosen substitute.

Measure for Measure was printed as a comedy in the first folio and continues to be classified as one, though its tone sometimes defies this classification.[1] Today it is often called one of Shakespeare's problem plays.

Characters

- Isabella, a novice and sister to Claudio,

- Mariana, betrothed to Angelo

- Juliet, beloved of Claudio, pregnant with his child

- Francisca, a nun.

- Mistress Overdone, the manager of a thriving Viennese brothel

- Vincentio, The Duke, who also appears disguised as Friar Lodowick

- Angelo, the Deputy, who rules in the Duke's absence

- Escalus, an ancient lord

- Claudio, a young gentleman, brother to Isabella

- Pompey Bum, a pimp who acquires customers for Mistress Overdone

- Lucio, a "fantastic", a foppish young nobleman

- Two gentlemen, friends to Lucio

- The Provost, who runs the prison

- Thomas and Peter, two friars

- Elbow, a simple constable

- Froth, a foolish gentleman of fourscore pound a year

- Abhorson, an executioner

- Barnardine, a dissolute prisoner

- a Justice, friend of Escalus

- Varrius (silent role), a friend of the Duke

Synopsis

Vincentio, the Duke of Vienna, makes it known that he intends to leave the city on a diplomatic mission. He leaves the government in the hands of a strict judge, Angelo.

In the next scene, we find a group of soldiers on a Vienna street, expressing their hopes, in irreverent banter, that a war with Hungary is afoot, and that they will be able to take part. Mistress Overdone, the operator of a brothel frequented by these same soldiers, appears and tells them "there's one yonder arrested and carried to prison was worth five thousand of you all". She tells them that it is "Signor Claudio", and that "within these three days his head to be chopped off" as punishment for "getting Madam Julietta with child". Lucio, one of the soldiers who is later revealed to be Claudio's friend, is astonished at this news and rushes off. Then comes Pompey Bum, who works for Mistress Overdone as a pimp, but disguises his profession by describing himself as a mere 'tapster' (the equivalent of a modern bartender), avers to the imprisonment of Claudio and outrageously explains his crime as "Groping for trouts in a peculiar river". He then informs Mistress Overdone of Angelo's new proclamation, that "All houses [of prostitution] in the suburbs of Vienna must be plucked down". The brothels in the city "shall stand for seed: they had gone down too, but that a wise burgher put in for them". Mistress Overdone is distraught, as her business is in the suburbs. "What shall become of me?" she asks. Pompey replies with a characteristic mixture of bawdy humor and folk-wisdom, "fear you not: good counselors lack no clients: though you change your place, you need not change your trade... Courage! there will be pity taken on you: you that have worn your eyes almost out in the service, you will be considered".

Claudio is then led past Pompey and Overdone on his way to prison, and explains what has happened to him. Claudio married Juliet, but, as they have not completed all the strict legal technicalities, they were still considered to be unmarried when Juliet became pregnant. Angelo, as the interim ruler of the city, decides to enforce a law that fornication is punishable by death, so Claudio is sentenced to be executed. Claudio's friend, Lucio, visits Claudio's sister, Isabella, a novice nun, and asks her to intercede with Angelo on Claudio's behalf.

_Robert_Smirke_(1753%E2%80%931845)_Royal_Shakespeare_Theatre.jpg.webp)

Isabella obtains an audience with Angelo, and pleads for mercy for Claudio. Over the course of two scenes between Angelo and Isabella, it becomes clear that he lusts after her, and he eventually offers her a deal: Angelo will spare Claudio's life if Isabella yields him her virginity. Isabella refuses, but when she threatens to publicly expose his lechery, he tells her that no one will believe her because his reputation is too austere. She then visits her brother in prison and counsels him to prepare himself for death. Claudio desperately begs Isabella to save his life, but Isabella refuses. She believes that it would be wrong for her to sacrifice her own immortal soul (and that of Claudio, if his entreaties were to convince her to lose her virtue) to save Claudio's transient earthly life.

The Duke has not in fact left the city, but remains there disguised as a friar (Lodowick) in order to secretly view the city's affairs, especially the effects of Angelo's strict enforcement of the law. In his guise as a friar, he befriends Isabella and arranges two tricks to thwart Angelo's evil intentions:

- First, a "bed trick" is arranged. Angelo has previously refused to fulfill the betrothal binding him to Mariana, because her dowry had been lost at sea. Isabella sends word to Angelo that she has decided to submit to him, but making it a condition of their meeting that it occurs in perfect darkness and in silence. Mariana agrees to take Isabella's place, and she has sex with Angelo, although he continues to believe he has enjoyed Isabella. (In some interpretations of the law, this constitutes consummation of their betrothal, and therefore their marriage. This same interpretation would also make Claudio's and Juliet's marriage legal.)

- After having sex with Mariana (whom he believes is Isabella), Angelo goes back on his word, sending a message to the prison that he wishes to see Claudio's head, necessitating the "head trick". The Duke first attempts to arrange the execution of another prisoner whose head can be sent instead of Claudio's. However, the villain Barnardine refuses to be executed in his drunken state. As luck would have it, a pirate named Ragozine, of similar appearance to Claudio, has recently died of a fever, so his head is sent to Angelo instead.

This main plot concludes with the 'return' to Vienna of the Duke as himself. Isabella and Mariana publicly petition him, and he hears their claims against Angelo, which Angelo smoothly denies. As the scene develops, it appears that Friar Lodowick will be blamed for the 'false' accusations leveled against Angelo. The Duke leaves Angelo to judge the cause against Lodowick, but returns in disguise moments later when Lodowick is summoned. Eventually, the friar is revealed to be the Duke, thereby exposing Angelo as a liar and Isabella and Mariana as truthful. He proposes that Angelo be executed but first compels him to marry Mariana—with his estate going to Mariana as her new dowry, "to buy you a better husband". Mariana pleads for Angelo's life, even enlisting the aid of Isabella (who is not yet aware her brother Claudio is still living). The Duke pretends not to heed the women's petition, and—only after revealing that Claudio has not, in fact, been executed—relents. The Duke then proposes marriage to Isabella. Isabella does not reply, and her reaction is interpreted differently in different productions: her silent acceptance of his proposal is the most common in performance. This is one of the "open silences" of the play.

A sub-plot concerns Claudio's friend Lucio, who frequently slanders the duke to the friar, and in the last act slanders the friar to the duke, providing opportunities for comic consternation on Vincentio's part and landing Lucio in trouble when it is revealed that the duke and the friar are one and the same. Lucio's punishment is to be forced into marrying Kate Keepdown, a prostitute whom he had impregnated and abandoned.

Sources

.jpg.webp)

The play draws on two distinct sources. The original is "The Story of Epitia", a story from Cinthio's Gli Hecatommithi, first published in 1565.[2] Shakespeare was familiar with this book as it contains the original source for Shakespeare's Othello. Cinthio also published the same story in a play version with some small differences, of which Shakespeare may or may not have been aware. The original story is an unmitigated tragedy in that Isabella's counterpart is forced to sleep with Angelo's counterpart, and her brother is still killed.

The other main source for the play is George Whetstone's 1578 lengthy two-part closet drama Promos and Cassandra, which itself is sourced from Cinthio. Whetstone adapted Cinthio's story by adding the comic elements and the bed and head tricks.[2]:20

The title of the play, which also appears as a line of dialogue, is commonly thought to be a biblical reference to the Sermon on the Mount Matthew 7:2:

For in the same way you judge others, you will be judged, and with the measure you use, it will be measured to you.[3]

Peter Meilaender has argued that Measure for Measure is largely based on biblical references, focusing on the themes of sin, restraint, mercy, and rebirth.[4]

Date, text and authorship

Measure for Measure is believed to have been written in 1603 or 1604. The play was first published in 1623 in the First Folio.

In their book Shakespeare Reshaped, 1606–1623, Gary Taylor and John Jowett argue that part of the text of Measure that survives today is not in its original form, but rather the product of a revision after Shakespeare's death by Thomas Middleton. They present stylistic evidence that patches of writing are by Middleton, and argue that Middleton changed the setting to Vienna from the original Italy.[5] Braunmuller and Watson summarize the case for Middleton, suggesting it should be seen as "an intriguing hypothesis rather than a fully proven attribution".[6] David Bevington suggests an alternate theory that the text can be stylistically credited to the professional scrivener Ralph Crane, who is usually credited for some of the better and unchanged texts in the Folio like that of The Tempest.[7]

It is generally accepted that a garbled sentence during the Duke's opening speech (lines 8–9 in most editions) represents a place where a line has been lost, possibly due to a printer's error. Because the folio is the only source, there is no possibility of recovering it.[7]

Analysis

The play's main themes include justice, "morality and mercy in Vienna", and the dichotomy between corruption and purity: "some rise by sin, and some by virtue fall". Mercy and virtue prevail, as the play does not end tragically, with virtues such as compassion and forgiveness being exercised at the end of the production. While the play focuses on justice overall, the final scene illustrates that Shakespeare intended for moral justice to temper strict civil justice: a number of the characters receive understanding and leniency, instead of the harsh punishment to which they, according to the law, could have been sentenced.[8]

Performance history

The earliest recorded performance of Measure for Measure took place on St. Stephen's night, 26 December 1604.

During the Restoration, Measure was one of many Shakespearean plays adapted to the tastes of a new audience. Sir William Davenant inserted Benedick and Beatrice from Much Ado About Nothing into his adaptation, called The Law Against Lovers. Samuel Pepys saw the hybrid play on 18 February 1662; he describes it in his Diary as "a good play, and well performed"—he was especially impressed by the singing and dancing of the young actress who played Viola, Beatrice's sister (Davenant's creation). Davenant rehabilitated Angelo, who is now only testing Isabella's chastity; the play ends with a triple marriage. This, among the earliest of Restoration adaptations, appears not to have succeeded on stage.

Charles Gildon returned to Shakespeare's text in a 1699 production at Lincoln's Inn Fields. Gildon's adaptation, entitled Beauty the Best Advocate, removes all of the low-comic characters. Moreover, by making both Angelo and Mariana, and Claudio and Juliet, secretly married, he eliminates almost all of the illicit sexuality that is so central to Shakespeare's play. In addition, he integrates into the play scenes from Henry Purcell's opera Dido and Aeneas, which Angelo watches sporadically throughout the play. Gildon also offers a partly facetious epilogue, spoken by Shakespeare's ghost, who complains of the constant revisions of his work. Like Davenant's, Gildon's version did not gain currency and was not revived.

John Rich presented a version closer to Shakespeare's original in 1720.[9]

In late Victorian times the subject matter of the play was deemed controversial, and there was an outcry when Adelaide Neilson appeared as Isabella in the 1870s.[10] The Oxford University Dramatic Society found it necessary to edit it when staging it in February 1906,[10] with Gervais Rentoul as Angelo and Maud Hoffman as Isabella, and the same text was used when Oscar Asche and Lily Brayton staged it at the Adelphi Theatre in the following month.[11]

William Poel produced the play in 1893 at the Royalty and in 1908 at the Gaiety in Manchester, with himself as Angelo. In line with his other Elizabethan performances, these used the uncut text of Shakespeare's original with only minimal alterations. The use of an unlocalised stage lacking scenery, and the swift, musical delivery of dramatic speech set the standard for the rapidity and continuity shown in modern productions. Poel's work also marked the first determined attempt by a producer to give a modern psychological or theological reading of both the characters and the overall message of the play.[12]

Notable 20th century productions of Measure for Measure include Charles Laughton as Angelo at the Old Vic Theatre in 1933, and Peter Brook's 1950 staging at the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre with John Gielgud as Angelo and Barbara Jefford as Isabella.[13] In 1957 John Houseman and Jack Landau directed a production at the Phoenix Theatre in New York City that featured Jerry Stiller and Richard Waring.[14] The play has only once been produced on Broadway, in a 1973 production also directed by Houseman that featured David Ogden Stiers as Vincentio, Kevin Kline in the small role of Friar Peter, and Patti Lupone in two small roles.[15] In 1976, there was a New York Shakespeare Festival production featuring Sam Waterston as the Duke, Meryl Streep as Isabella, John Cazale as Angelo, Lenny Baker as Lucio, Jeffrey Tambor as Elbow, and Judith Light as Francisca.[16] In April 1981 director Michael Rudman presented a version with an all-black cast at London's National Theatre.[17] Rudman re-staged his concept at the New York Shakespeare Festival in 1993, starring Kevin Kline as the Duke with André Braugher as Angelo and Lisa Gay Hamilton as Isabella.[18]

Between 2013 and 2017, theatre company Cheek by Jowl staged a Russian-language version of the play in association with the Pushkin Theatre, Moscow, and the Barbican Centre, London. The production was directed by Declan Donnellan and designed by Nick Ormerod.[19][20]

In 2018, Josie Rourke directed a uniquely gender-reversal production of the play at the Donmar Warehouse in London, in which Jack Lowden and Hayley Atwell successively alternate the roles of Angelo and Isabella.[21][22]

Adaptations and cultural references

Film adaptations

- 1979 BBC version shot on videotape, directed by Desmond Davis, generally considered to be a faithful rendition of the play. Kate Nelligan plays Isabella, Tim Pigott-Smith plays Angelo and Kenneth Colley plays the Duke. Shown on PBS in the United States as part of the BBC Television Shakespeare series.

- 1994 TV adaptation set in the present, starring Tom Wilkinson, Corin Redgrave and Juliet Aubrey.

- In the 2006 version, directed by Bob Komar, the play is set in the modern-day British Army. It stars Josephine Rogers as Isabella, Daniel Roberts as Angelo, and Simon Phillips as the Duke.[23]

- The 2015 film M4M: Measure for Measure re-contextualizes Isabella's character changing her gender from female to male. Thus making this version the first to incorporate homosexual interactions.[24]

- A 2019 Australian feature film adaptation directed by Paul Ireland, set in modern-day Melbourne.

Radio adaptations

- In 2004, BBC Radio 3's Drama on 3 broadcast a production directed by Claire Grove, with Chiwetel Ejiofor as The Duke, Nadine Marshall as Isabella, Anton Lesser as Angelo, Adjoa Andoh as Mariana, Jude Akuwudike as Claudio, Colin McFarlane as The Provost and Claire Benedict as Mistress Overdone.[25]

- On 29 April 2018, BBC Radio 3's Drama on 3 broadcast a new production directed by Gaynor Macfarlane, with Paul Higgins as The Duke, Nicola Ferguson as Isabella, Robert Jack as Angelo, Maureen Beattie as Escalus, Finn den Hertog as Lucio/Froth, Michael Nardone as The Provost, Maggie Service as Mariana, Owen Whitelaw as Claudio/Friar Peter, Sandy Grierson as Pompey and Georgie Glen as Mistress Overdone/Francisca.[26]

Musical adaptations

- The opera Das Liebesverbot (1836) by Richard Wagner with the libretto written by the composer based on Measure for Measure

- The musical Desperate Measures (2004), with book and lyrics by Peter Kellogg and music by David Friedman

In popular culture

- The character of Mariana inspired Tennyson for his poem "Mariana" (1830).[27]

- The plot of the play was taken by Alexander Pushkin in his poetic tale Angelo (1833). Pushkin had begun to translate the Shakespearean play, but finally arrived at a generally non-dramatic tale with some dialogue scenes.[28]

- Joyce Carol Oates' short story "In the Region of Ice" contains the dialog between Claudio and his sister, and also parallels the same plea with the student, Allen Weinstein, and his teacher, Sister Irene.

- The Bertolt Brecht play, Round Heads and Pointed Heads, was originally written as an adaptation of Measure for Measure.[29]

- Thomas Pynchon's early short-story, "Mortality and Mercy in Vienna", takes its title from a verse in this play, and has also been inspired by it.

- Mr. Beavis, in Aldous Huxley's Eyeless in Gaza, compares a "tingling warmth" he feels while listening to Mrs. Foxe reading the last scene of Measure for Measure.[30]

- The title for Aldous Huxley's 1948 novel, Ape and Essence, came from a line spoken by Isabella, act 2 scene 2: "His glassy essence, like an angry ape".[31]

- Lauren Willig's 2011 novel Two L is based on Measure for Measure.

References

- "Measure for Measure Tone".

- N. W. Bawcutt (ed.), Measure for Measure (Oxford, 1991), p. 17

- Magedanz, Stacy (2004). "Public Justice and Private Mercy in Measure for Measure". SEL: Studies in English Literature 1500–1900. 44 (2, Tudor and Stuart Drama): 317–332. eISSN 1522-9270. ISSN 0039-3657. JSTOR 3844632.

- Meilaender, Peter C. (2012). "Marriage and the Law: Politics and Theology in Measure for Measure". Perspectives on Political Science. 41 (4): 195–200. doi:10.1080/10457097.2012.713263.

- Gary Taylor and John Jowett, Shakespeare Reshaped, 1606–1623 (Oxford University Press, 1993). See also "Shakespeare's Mediterranean Measure for Measure", in Shakespeare and the Mediterranean: The Selected Proceedings of the International Shakespeare Association World Congress, Valencia, 2001, ed. Tom Clayton, Susan Brock, and Vicente Forés (Newark: University of Delaware Press, 2004), 243–269.

- Shakespeare, William (2020). A.R. Braunmuller; Robert N. Watson (eds.). Measure for Measure (Third Series ed.). London: The Arden Shakespeare. p. 372. ISBN 978-1-904-27143-7.

- Shakespeare, William (1997). David Bevington (ed.). The Complete Works (Updated Fourth ed.). New York: Addison-Wesley Longman. p. A-7. ISBN 978-0-673-99996-2.

- Whitlow, Roger (1978). "Measure for Measure: Shakespearean Morality and the Christian Ethic". Encounter. 39 (2): 165–173 – via EBSCOhost.

- F. E. Halliday (1964). A Shakespeare Companion 1564–1964, Baltimore: Penguin, pp. 273, 309–310.

- Times review 23 February 1906

- Times review 21 March 1906

- S. Nagarajan (1998). Measure for Measure, New York, Penguin, pp. 181–183.

- "Archive theatre review: Measure for Measure". The Guardian. 18 December 2008. Retrieved 23 December 2017.

- "Measure for Measure". Internet Broadway Database. Retrieved 23 November 2017.

- "Measure for Measure". Internet Broadway Database. Retrieved 23 November 2017.

- Foote, Timothy, "License in the Park", Time, 23 August 1976, p. 57

- MacMillan, Michael (2016). "Conversations with black actors". In Jarrett-Macauley, Delia (ed.). Shakespeare, Race and Performance: The Diverse Bard. London: Routledge. p. 124. ISBN 978-1-138-91382-0.

- Simon, John (2 August 1993). "As Who Likes it?". New York Magazine: 57.

- "Cheek by Jowl Website: Previous Productions". information. London: Cheek by Jowl Theatre Company. 10 April 2015. Retrieved 25 October 2017.

- Gardner, Lyn (19 April 2015). "Measure for Measure review". The Guardian. Retrieved 23 November 2017.

- Brown, Mark. "Measure for Measure gender swap may be theatrical first". The Guardian. 24 April 2018.

- Snow, Georgia. "Hayley Atwell and Jack Lowden to swap roles in Donmar Warehouse Measure for Measure". The Stage. 24 April 2018.

- Rogers, Josephine; Roberts, Daniel; Phillips, Simon; Agerwald, Emma (1 September 2006), Measure for Measure, retrieved 8 March 2017

- Adler, Howard; Alford, Jarod Christopher; Asher, Howard; Benjamin, Jeremiah (28 February 2013), M4M: Measure for Measure, retrieved 8 March 2017

- https://www.bbashakespeare.warwick.ac.uk/productions/measure-measure-2004-bbc-bbc-radio-3

- "BBC Radio 3 – Drama on 3, Measure for Measure".

- Pattison, Robert (1979). Tennyson and tradition. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard U.P. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-674-87415-2.

- O'Neil, Catherine (2003). "Of Monarchs and Mercy". With Shakespeare's Eyes: Pushkin's Creative Appropriation of Shakespeare. University of Delaware Press. p. 69.

- Parker, Stephen (2014). Bertolt Brecht : a literary life. London: Bloomsbury. p. 300. ISBN 978-1-4081-5563-9.

- p. 81 in the 2004 Vintage Classics edition ISBN 0-09-945817-9

- Zigler, Ronald Lee (2015). The Educational Prophecies of Aldous Huxley. New York: Routledge. p. 65. ISBN 978-1-138-83249-7.

External links

- Measure for Measure

- Measure for Measure at Project Gutenberg

- Measure for Measure – BFI Shakespeare on Screen

Measure for Measure public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Measure for Measure public domain audiobook at LibriVox- Measure for Measure feature film, on IMDB

- Measure for Measure Comic – a parody webcomic adaptation of the play

- Sparknotes – Measure For Measure – Sparknotes' interpretation of key themes, scenes and characters

- Crossref-it.info – Measure For Measure – Synopsis, key themes, characters, literary and cultural background

.png.webp)