Meningioma

Meningioma, also known as meningeal tumor, is typically a slow-growing tumor that forms from the meninges, the membranous layers surrounding the brain and spinal cord.[1] Symptoms depend on the location and occur as a result of the tumor pressing on nearby tissue.[3][6] Many cases never produce symptoms.[2] Occasionally seizures, dementia, trouble talking, vision problems, one sided weakness, or loss of bladder control may occur.[2]

| Meningioma | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Meningeal tumor[1] |

| |

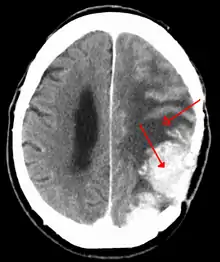

| A contrast-enhanced CT scan of the brain, demonstrating the appearance of a meningioma | |

| Specialty | Neurosurgery |

| Symptoms | None, seizures, dementia, trouble talking, vision problems, one sided weakness[2] |

| Usual onset | Adults[1] |

| Types | Grade I, II, III[1] |

| Risk factors | Ionizing radiation, family history[3] |

| Diagnostic method | Medical imaging[2] |

| Differential diagnosis | Haemangiopericytoma, lymphoma, schwannoma, solitary fibrous tumour, metastasis[4] |

| Treatment | Observation, surgery, radiation therapy[2] |

| Medication | Anticonvulsants, corticosteroids[2] |

| Prognosis | 95% ten year survival with complete removal[5] |

| Frequency | c. 1 per 1,000 (US)[3] |

Risk factors include exposure to ionizing radiation such as during radiation therapy, a family history of the condition, and neurofibromatosis type 2.[2][3] As of 2014 they do not appear to be related to cell phone use.[6] They appear to be able to form from a number of different types of cells including arachnoid cells.[1][2] Diagnosis is typically by medical imaging.[2]

If there are no symptoms, periodic observation may be all that is required.[2] Most cases that result in symptoms can be cured by surgery.[1] Following complete removal fewer than 20% recur.[2] If surgery is not possible or all the tumor cannot be removed radiosurgery may be helpful.[2] Chemotherapy has not been found to be useful.[2] A small percentage grow rapidly and are associated with worse outcomes.[1]

About one per thousand people in the United States are currently affected.[3] Onset is usually in adults.[1] In this group they represent about 30% of brain tumors.[4] Women are affected about twice as often as men.[3] Meningiomas were reported as early as 1614 by Felix Plater.[7]

Signs and symptoms

Small tumors (e.g., < 2.0 cm) usually are incidental findings at autopsy without having caused symptoms. Larger tumors may cause symptoms, depending on the size and location.

- Focal seizures may be caused by meningiomas that overlie the cerebrum.

- Progressive spastic weakness in legs and incontinence may be caused by tumors that overlie the parasagittal frontoparietal region.

- Tumors of the Sylvian aqueduct may cause myriad motor, sensory, aphasic, and seizure symptoms, depending on the location.

- Increased intracranial pressure eventually occurs, but is less frequent than in gliomas.

- Diplopia (Double vision) or uneven pupil size may be symptoms if related pressure causes a third and/or sixth nerve palsy.

Causes

The causes of meningiomas are not well understood.[8] Most cases are sporadic, appearing randomly, while some are familial. Persons who have undergone radiation, especially to the scalp, are more at risk for developing meningiomas, as are those who have had a brain injury.[9] Atomic bomb survivors from Hiroshima had a higher than typical frequency of developing meningiomas, with the incidence increasing the closer that they were to the site of the explosion. Dental x-rays are correlated with an increased risk of meningioma, in particular for people who had frequent dental x-rays in the past, when the x-ray dose of a dental x-ray was higher than in the present.[10]

Having excess body fat increases the risk.[11]

A 2012 review found that mobile telephone use was unrelated to meningioma.[12]

People with neurofibromatosis type 2 (NF-2) have a 50% chance of developing one or more meningiomas.

Ninety-two percent of meningiomas are benign. Eight percent are either atypical or malignant.[7]

Genetics

The most frequent genetic mutations (~50%) involved in meningiomas are inactivation mutations in the neurofibromatosis 2 gene (merlin) on chromosome 22q.

TRAF7 mutations are present in about one-fourth of meningiomas. Mutations in the TRAF7, KLF4, AKT1, and SMO genes are commonly expressed in benign skull-base meningiomas. Mutations in NF2 are commonly expressed in meningiomas located in the cerebral and cerebellar hemispheres.[13]

Pathophysiology

Meningiomas arise from arachnoidal cells,[14] most of which are near the vicinity of the venous sinuses, and this is the site of greatest prevalence for meningioma formation. They most frequently are attached to the dura over the superior parasagittal surface of frontal and parietal lobes, along the sphenoid ridge, in the olfactory grooves, the sylvian region, superior cerebellum along the falx cerebri, cerebellopontine angle, and the spinal cord. The tumor is usually gray, well-circumscribed, and takes on the form of the space it occupies. They usually are dome-shaped, with the base lying on the dura.

Locations

- Parasagittal/falcine (25%)

- Convexity (surface of the brain) (19%)

- Sphenoid ridge (17%)

- Suprasellar (9%)

- Posterior fossa (8%)

- Olfactory groove (8%)

- Middle fossa/Meckel's cave (4%)

- Tentorial (3%)

- Peri-torcular (3%)

Other uncommon locations are the lateral ventricle, foramen magnum, and the orbit/optic nerve sheath.[7] Meningiomas also may occur as a spinal tumor, more often in women than in men. This occurs more often in Western countries than Asian.

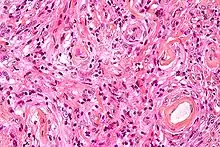

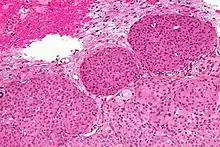

Histologically, meningioma cells are relatively uniform, with a tendency to encircle one another, forming whorls and psammoma bodies (laminated calcific concretions).[15] As such, they also have a tendency to calcify and are highly vascularized.

Meningiomas often are considered benign tumors that can be removed by surgery, but most recurrent meningiomas correspond to histologic benign tumors. The metabolic phenotype of these benign recurrent meningiomas indicated an aggressive metabolism resembling that observed for atypical meningioma.[16]

Diagnosis

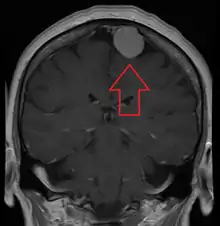

Meningiomas are visualized readily with contrast CT, MRI with gadolinium,[17] and arteriography, all attributed to the fact that meningiomas are extra-axial and vascularized. CSF protein levels are usually found to be elevated when lumbar puncture is used to obtain spinal fluid.

Although the majority of meningiomas are benign, they may have malignant presentations. Classification of meningiomas are based upon the WHO classification system.[18]

- Benign (Grade I) – (90%) – meningothelial, fibrous, transitional, psammomatous, angioblastic

- Atypical (Grade II) – (7%) – chordoid, clear cell, atypical (includes brain invasion)

- Anaplastic/malignant (Grade III) – (2%) – papillary, rhabdoid, anaplastic (most aggressive)

In a 2008 review of the latter two categories, atypical and anaplastic-meningioma cases, the mean overall survival for atypical meningiomas was found to be 11.9 years vs. 3.3 years for anaplastic meningiomas. Mean relapse-free survival for atypical meningiomas was 11.5 years vs. 2.7 years for anaplastic meningiomas.[19]

Malignant anaplastic meningioma is an especially malignant tumor with aggressive behavior. Even if, by general rule, neoplasms of the nervous system (brain tumors) cannot metastasize into the body because of the blood–brain barrier, anaplastic meningioma can. Although they are inside the cerebral cavity, they are located on the bloodside of the BBB, because meningiomas tend to be connected to blood vessels. Thus, cancerized cells can escape into the bloodstream, which is why meningiomas, when they metastasize, often turn up around the lungs.

Anaplastic meningioma and hemangiopericytoma are difficult to distinguish, even by pathological means, as they look similar, especially, if the first occurrence is a meningeal tumor, and both tumors occur in the same types of tissue.

Although usually benign a "petro-clival" menigioma is typically fatal without treatment due to its location. Until the 1970s no treatment was available for this type of meningioma however since that time a range of surgical and radiological treatments have evolved. Nevertheless the treatment of this type of meningioma remains a challenge with relatively frequent poor outcomes.[20]

Prevention

The risk of meningioma can be reduced by maintaining a normal body weight,[21] and by avoiding unnecessary dental x-rays.[22]

Treatment

Observation

Observation with close imaging follow-up may be used in select cases if a meningioma is small and asymptomatic. In a retrospective study on 43 patients, 63% of patients were found to have no growth on follow-up, and the 37% found to have growth at an average of 4 mm / year.[23] In this study, younger patients were found to have tumors that were more likely to have grown on repeat imaging; thus are poorer candidates for observation. In another study, clinical outcomes were compared for 213 patients undergoing surgery vs. 351 patients under watchful observation.[24] Only 6% of the conservatively treated patients developed symptoms later, while among the surgically treated patients, 5.6% developed persistent morbid condition, and 9.4% developed surgery-related morbid condition.

Observation is not recommended in tumors already causing symptoms. Furthermore, close follow-up with imaging is required with an observation strategy to rule out an enlarging tumor.[25]

Surgery

Meningiomas usually can be surgically resected (removed) and result in a permanent cure if the tumor is superficial on the dural surface and easily accessible. Transarterial embolization has become a standard preoperative procedure in the preoperative management.[26] If invasion of the adjacent bone occurs, total removal is nearly impossible. It is rare for benign meningiomas to become malignant.

The probability of a tumor recurring or growing after surgery may be estimated by comparing the tumor's WHO (World Health Organization) grade and by the extent of surgery by the Simpson Criteria.[27]

| Simpson Grade | Completeness of Resection | 10-year Recurrence |

|---|---|---|

| Grade I | complete removal including resection of underlying bone and associated dura | 9% |

| Grade II | complete removal and coagulation of dural attachment | 19% |

| Grade III | complete removal without resection of dura or coagulation | 29% |

| Grade IV | subtotal resection | 40% |

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy may include photon-beam or proton-beam treatment, or fractionated external beam radiation. Radiosurgery may be used in lieu of surgery in small tumors located away from critical structures.[28] Fractionated external-beam radiation also can be used as primary treatment for tumors that are surgically unresectable or, for patients who are inoperable for medical reasons.

Radiation therapy often is considered for WHO grade I meningiomas after subtotal (incomplete) tumor resections. The clinical decision to irradiate after a subtotal resection is somewhat controversial, as no class I randomized, controlled trials exist on the subject.[29] Numerous retrospective studies, however, have suggested strongly that the addition of postoperative radiation to incomplete resections improves both progression-free survival (i.e. prevents tumor recurrence) and improves overall survival.[30]

In the case of a grade III meningioma, the current standard of care involves postoperative radiation treatment regardless of the degree of surgical resection.[31] This is due to the proportionally higher rate of local recurrence for these higher-grade tumors. Grade II tumors may behave variably and there is no standard of whether to give radiotherapy following a gross total resection. Subtotally resected grade II tumors should be radiated.

Chemotherapy

Likely, current chemotherapies are not effective. Antiprogestin agents have been used, but with variable results.[32] A 2007 study of whether hydroxyurea has the capacity to shrink unresectable or recurrent meningiomas is being further evaluated.[33]

Epidemiology

Many individuals have meningiomas, but remain asymptomatic, so the meningiomas are discovered during an autopsy. One to two percent of all autopsies reveal meningiomas that were unknown to the individuals during their lifetime, since there were never any symptoms. In the 1970s, tumors causing symptoms were discovered in 2 out of 100,000 people, while tumors discovered without causing symptoms occurred in 5.7 out of 100,000, for a total incidence of 7.7/100,000. With the advent of modern sophisticated imaging systems such as CT scans, the discovery of asymptomatic meningiomas has tripled.

Meningiomas are more likely to appear in women than men, though when they appear in men, they are more likely to be malignant. Meningiomas may appear at any age, but most commonly are noticed in men and women age 50 or older, with meningiomas becoming more likely with age. They have been observed in all cultures, Western and Eastern, in roughly the same statistical frequency as other possible brain tumors.[7]

History

The neoplasms currently referred to as meningiomas were referred to with a wide range of names in older medical literature, depending on the source. Various descriptors included "fungoid tumors", "fungus of the dura mater", "epithelioma", "psammoma", "dural sarcoma", "dural endothelioma", "fibrosarcoma", "angioendothelioma", "arachnoidal fibroboastoma", "endotheliosis of the meninges", "meningeal fibroblastoma", "meningoblastoma", "mestothelioma of the meninges", "sarcoma of the dura", and others.

The modern term of "meningioma" was used first by Harvey Cushing (1869–1939) in 1922, to describe a set of tumors that occur throughout the neuraxis (brain and spinal cord), but have various commonalities.[34][35] Charles Oberling then separated these into subtypes based on cell structure and, over the years, several other researchers have defined dozens of different subtypes as well. In 1979, the World Health Organization (WHO) classified seven subtypes, upgraded in 2000 to a classification system with nine low-grade variants (grade I tumors) and three variants each of grade II and grade III meningiomas.[35] The most common subtypes are Meningotheliomatous (63%), transitional or mixed-type (19%), fibrous (13%), and psammomatous (2%).[7]

The earliest evidence of a probable meningioma is from a skull approximately 365,000 years old, which was found in Germany. Other probable examples have been discovered in other continents around the world, including North and South America, and Africa.

The earliest written record of what was probably a meningioma is from the 1600s, when Felix Plater (1536–1614) of the University of Basel performed an autopsy on Sir Caspar Bonecurtius.[34] Surgery for removal of meningiomas was first attempted in the sixteenth century, but the first known successful surgery for removal of a meningioma of the convexity (parasagittal) was performed in 1770 by Anoine Luis.[36] The first documented successful removal of a skull base meningioma was performed in 1835 by Zanobi Pecchioli, Professor of Surgery at the University of Siena.[7] Other notable meningioma researchers have been William Macewen (1848–1924), and William W. Keen (1837–1932).[34]

Improvements in meningioma research and treatment over the last century have occurred in terms of the surgical techniques for removal of the tumor, and related improvements in anesthesia, antiseptic methods, techniques to control blood loss, better ability to determine which tumors are and are not operable,[37] and to effectively differentiate between the different meningioma subtypes.[38]

Notable cases

- Leonard Wood (1860–1927), underwent successful surgery by Dr. Harvey Cushing for a meningioma circa 1910, a major advance in neurosurgery at the time.[34]

- Crystal Lee Sutton (1940–2009), American union organizer and inspiration for the film Norma Rae, died of a malignant meningioma.[39][40]

- Elizabeth Taylor (1932-2011), American actress, underwent surgery in February 1997 to remove a benign meningioma.[41]

- Kathi Goertzen (1958–2012), television news anchor in Seattle who underwent a very public battle with recurring tumors. She died on August 13, 2012, of complications related to her treatment.[42]

- Eileen Ford (1922–2014), American model agency executive and co-founder of Ford Models. Died on July 9, 2014, from complications of meningioma and osteoporosis.[43]

- Mary Tyler Moore (1936–2017), American actress, underwent surgery in May 2011 to remove a benign meningioma.[44][45]

- Jack Daulton (1956–), American trial lawyer and art collector, underwent three surgeries in 2011-2012 in connection with the removal of a golf-ball-size benign meningioma over his left motor cortex; he fully recovered without disability or recurrence.[46]

See also

References

- "Adult Central Nervous System Tumors Treatment". National Cancer Institute. 26 August 2016. Archived from the original on 28 July 2017.

- Ferri, Fred F. (2017). Ferri's Clinical Advisor 2018 E-Book: 5 Books in 1. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 809. ISBN 9780323529570. Archived from the original on 2017-09-10.

- Wiemels, J; Wrensch, M; Claus, EB (September 2010). "Epidemiology and etiology of meningioma". Journal of Neuro-Oncology. 99 (3): 307–14. doi:10.1007/s11060-010-0386-3. PMC 2945461. PMID 20821343.

- Starr, CJ; Cha, S (26 May 2017). "Meningioma mimics: five key imaging features to differentiate them from meningiomas". Clinical Radiology. 72 (9): 722–728. doi:10.1016/j.crad.2017.05.002. PMID 28554578.

- Goodman, Catherine C.; Fuller, Kenda S. (2011). Pathology for the Physical Therapist Assistant – E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 192. ISBN 978-1437708936. Archived from the original on 2017-09-10.

- World Cancer Report 2014. World Health Organization. 2014. pp. Chapter 5.16. ISBN 978-9283204299.

- Joung H. Lee (2008-12-11). Meningiomas: Diagnosis, Treatment, and Outcome. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 3–13. ISBN 978-1-84628-784-8.

- "Meningioma". Mayo Clinic. Archived from the original on February 28, 2012. Retrieved February 27, 2012.

- Longstreth WT, Dennis LK, McGuire VM, Drangsholt MT, Koepsell TD (August 1993). "Epidemiology of intracranial meningioma". Cancer. 72 (3): 639–48. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(19930801)72:3<639::AID-CNCR2820720304>3.0.CO;2-P. PMID 8334619.

- Claus EB, Calvocoressi L, Bondy ML, Schildkraut JM, Wiemels JL, Wrensch M (September 2012). "Dental x-rays and risk of meningioma". Cancer. 118 (18): 4530–7. doi:10.1002/cncr.26625. PMC 3396782. PMID 22492363.

- Niedermaier, T; Behrens, G; Schmid, D; Schlecht, I; Fischer, B; Leitzmann, MF (16 September 2015). "Body mass index, physical activity, and risk of adult meningioma and glioma: A meta-analysis". Neurology. 85 (15): 1342–50. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000002020. PMID 26377253.

- Repacholi, MH; Lerchl, A; Röösli, M; Sienkiewicz, Z; Auvinen, A; Breckenkamp, J; d'Inzeo, G; Elliott, P; Frei, P; Heinrich, S; Lagroye, I; Lahkola, A; McCormick, DL; Thomas, S; Vecchia, P (April 2012). "Systematic review of wireless phone use and brain cancer and other head tumors". Bioelectromagnetics. 33 (3): 187–206. Bibcode:2009BioEl..30...45D. doi:10.1002/bem.20716. PMID 22021071.

- Victoria E Clark; E. Zyenep Erson-Omay; Akdes Serin; et al. (March 2013). "Genomic analysis of non-NF2 meningiomas reveals mutations in TRAF7, KLF4, AKT1, and SMO". Science. 339 (6123): 1077–80. Bibcode:2013Sci...339.1077C. doi:10.1126/science.1233009. PMC 4808587. PMID 23348505.

- "moon.ouhsc.edu". Archived from the original on 2008-12-05. Retrieved 2008-11-30.

- "Neuropathology For Medical Students". Archived from the original on 2009-01-07. Retrieved 2008-11-30.

- Monleón D, Morales JM, Gonzalez-Segura A, Gonzalez-Darder JM, Gil-Benso R, Cerdá-Nicolás M, López-Ginés C (November 2010). "Metabolic aggressiveness in benign meningiomas with chromosomal instabilities". Cancer Research. 70 (21): 8426–8434. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1498. PMID 20861191. Archived from the original on 2017-02-14. Retrieved 2011-07-12.

- "Meningioma]". Radiopaedia.

- Wrobel G, Roerig P, Kokocinski F, et al. (March 2005). "Microarray-based gene expression profiling of benign, atypical and anaplastic meningiomas identifies novel genes associated with meningioma progression". Int. J. Cancer. 114 (2): 249–56. doi:10.1002/ijc.20733. PMID 15540215.

- Yang SY, Park CK, Park SH, Kim DG, Chung YS, Jung HW (May 2008). "Atypical and anaplastic meningiomas: prognostic implications of clinicopathological features". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 79 (5): 574–80. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2007.121582. hdl:10371/62023. PMID 17766430.

- Maurer, AJ; Safavi-Abbasi, S; Cheema, AA; Glenn, CA; Sughrue, ME (October 2014). "Management of petroclival meningiomas: a review of the development of current therapy". Journal of Neurological Surgery. Part B, Skull Base. 75 (5): 358–67. doi:10.1055/s-0034-1373657. PMC 4176539. PMID 25276602.

- Lauby-Secretan, B; Scoccianti, C; Loomis, D; Grosse, Y; Bianchini, F; Straif, K; International Agency for Research on Cancer Handbook Working, Group (25 August 2016). "Body Fatness and Cancer – Viewpoint of the IARC Working Group". The New England Journal of Medicine. 375 (8): 794–798. doi:10.1056/nejmsr1606602. PMC 6754861. PMID 27557308.

- "Dental X-rays Linked to Brain Tumors". Archived from the original on 2016-09-27. Retrieved 2016-09-23.

- Herscovici Z, et al. (Sep 2004). "Natural history of conservatively treated meningiomas". Neurology. 63 (6): 1133–4. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000138569.45818.50. PMID 15452322.

- Yano S, Kuratsu J (2006). "Indications for surgery in patients with asymptomatic meningiomas based on an extensive experience". J Neurosurg. 105 (4): 538–43. doi:10.3171/jns.2006.105.4.538. PMID 17044555.

- Olivero WC, et al. (Aug 1995). "The natural history and growth rate of asymptomatic meningiomas: a review of 60 patients". J Neurosurg. 83 (2): 222–4. doi:10.3171/jns.1995.83.2.0222. PMID 7616265.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-01-10. Retrieved 2007-01-02.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Simpson D (Feb 1957). "The recurrence of intracranial meningiomas after surgical treatment". J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 20 (1): 22–39. doi:10.1136/jnnp.20.1.22. PMC 497230. PMID 13406590.

- Kollová A, Liscák R, Novotný J, Vladyka V, Simonová G, Janousková L (August 2007). "Gamma Knife surgery for benign meningioma". Journal of Neurosurgery. 107 (2): 325–36. doi:10.3171/JNS-07/08/0325. PMID 17695387.

- Taylor BW, Marcus RB, Friedman WA, Ballinger WE, Million RR (August 1988). "The meningioma controversy: postoperative radiation therapy". International Journal of Radiation Oncology, Biology, Physics. 15 (2): 299–304. doi:10.1016/S0360-3016(98)90008-6. PMID 3403313.

- Goldsmith BJ, et al. (1994). "Postoperative irradiation for subtotally resected meningiomas. A retrospective analysis of 140 patients treated from 1967 to 1990". J Neurosurg. 80 (2): 195–201. doi:10.3171/jns.1994.80.2.0195. PMID 8283256.

- Goyal LK, Suh JH, Mohan DS, Prayson RA, Lee J, Barnett GH (January 2000). "Local control and overall survival in atypical meningioma: a retrospective study". International Journal of Radiation Oncology, Biology, Physics. 46 (1): 57–61. doi:10.1016/S0360-3016(99)00349-1. PMID 10656373.

- Wahab M, Al-Azzawi F (December 2003). "Meningioma and hormonal influences". Climacteric. 6 (4): 285–92. doi:10.1080/cmt.6.4.285.292. PMID 15006250.

- Newton HB (2007). "Hydroxyurea chemotherapy in the treatment of meningiomas". Neurosurg Focus. 23 (4): E11. doi:10.3171/foc-07/10/e11. PMID 17961035.

- Okonkwo DO, Laws ER (2009). "Meningiomas: Historical Perspective". Meningiomas. pp. 3–10. doi:10.1007/978-1-84628-784-8_1. ISBN 978-1-84882-910-7.

- Prayson RA (2009). "Pathology of Meningiomas". Meningiomas. pp. 31–43. doi:10.1007/978-1-84628-784-8_5. ISBN 978-1-84882-910-7.

- Louis A (1774). "Mêmoire sur les Tumeurs Fungueuses de la Dure-mère". Mem Acad Roy Chir. 5: 1–59.

- DeMonte, Franco; Ossama Al-Mefty; Michael McDermott (2011). Al-Mefty's Meningiomas (2nd ed.). Thieme. ISBN 978-1-60406-053-9.

- Al-Kadi, OS (April 2015). "A multiresolution clinical decision support system based on fractal model design for classification of histological brain tumours". Computerized Medical Imaging and Graphics. 41: 67–79. arXiv:1512.08051. doi:10.1016/j.compmedimag.2014.05.013. PMID 24962336.

- Handgraaf, Brie (2008-06-28). "Real 'Norma Rae' has new battle involving cancer". The Times-News. Archived from the original on 2012-03-02. Retrieved 2012-02-25.

- Sturgis, Sue (2009-09-14). "Real 'Norma Rae' dies of cancer after insurer delayed treatment". Facing South. Institute for Southern Studies. Archived from the original on 2013-10-27. Retrieved 2012-02-25.

- "Elizabeth Taylor home from hospital after brain surgery". CNN News. February 26, 1997. Retrieved 2018-12-31.

- Staff (February 6, 2013). "News anchor Kathi Goertzen dies after long illness". CBS-Channel 5 KING. Archived from the original on April 3, 2015. Retrieved March 5, 2015.

- Notice of death of Eileen Ford, with causes provided Archived 2014-07-13 at the Wayback Machine, CNN.com, July 10, 2014; accessed July 13, 2014.

- Goldman, Russell (May 12, 2011). "Mary Tyler Moore has brain surgery for meningioma tumor". ABC News. Archived from the original on February 21, 2012. Retrieved 2012-02-25.

- Genzlinger, Neil (January 26, 2012). "Boy, did she make it". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 15, 2012. Retrieved February 25, 2012.

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Bljirn0Gkyc&t=57s

External links

- MR/CT scans of meningioma from MedPix

- MR/CT scans of pneumosinus dilatans from MedPix

- Cancer.Net: Meningioma

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |