Mercury 13

The Mercury 13 were thirteen American women who, as part of a privately funded program, successfully underwent the same physiological screening tests as had the astronauts selected by NASA on April 9, 1959, for Project Mercury. The term was coined in 1995 by Hollywood producer James Cross as a comparison to the Mercury Seven name given to the selected male astronauts. The Mercury 13 women were not part of NASA's astronaut program, never flew in space, and never met as a group.

In the 1960s some of these women were among those who lobbied the White House and Congress to have women included in the astronaut program. They testified before a congressional committee in 1962. Clare Boothe Luce wrote an article for LIFE magazine publicizing the women and criticizing NASA for its failure to include women as astronauts.

History

When NASA first planned to put people in space, they believed that the best candidates would be pilots, sub crews or members of expeditions to the Antarctica or the Arctic areas. They also thought people with more extreme sports backgrounds, such as parachuting, climbing, deep sea diving, etc. would also excel in the program.

NASA knew that numerous people would apply for this opportunity and testing would be expensive. President Dwight Eisenhower believed that military test pilots would make the best astronauts and had already passed rigorous testing and training within the government. This greatly altered the testing requirements and shifted the history of who was chosen to go to space originally.

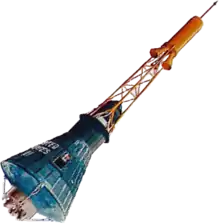

William Randolph Lovelace II, former Flight Surgeon and later, chairman of the NASA Special Advisory Committee on Life Science, helped develop the tests for NASA's male astronauts and became curious to know how women would do taking the same tests. In 1960, Lovelace and Air Force Brig. General Don Flickinger invited Geraldyn "Jerrie" Cobb, known as an accomplished pilot, to undergo the same rigorous challenges as the men.[1]

Lovelace became interested in beginning this program because he was a medical doctor who had done the NASA physical testing for the official program. He was able to fund the unofficial program, and invited up to 25 women to come and take the physical tests. Lovelace was interested in the way that women's bodies would react to being in space. Although the program was privately funded, the program was hidden from the public eye. The Mercury 13 were not reported in any major publications, but they were not unknown.

Cobb was the first American woman (and the only one of the Mercury 13) to undergo and pass all three phases of testing. Lovelace and Cobb recruited 19 more women to take the tests, financed by the husband of world-renowned aviator Jacqueline Cochran. Thirteen of the women passed the same tests as had the Mercury 7. Some were disqualified due to brain or heart anomalies. The results were announced at the second International Symposium on Submarine and Space Medicine in Stockholm, Sweden on August 18, 1960.[2]

Candidate background

All of the candidates were accomplished pilots; Lovelace and Cobb reviewed the records of more than 700 women pilots in order to select candidates. They did not invite anyone with fewer than 1,000 hours of flight experience. Some of the women may have been recruited through the Ninety-Nines, a women pilot's organization of which Cobb was also a member. Some women responded after hearing about the opportunity through friends.

This group of women, whom Jerrie Cobb called the First Lady Astronaut Trainees (FLATs), accepted the challenge to be tested for a research program.[1]

Wally Funk wrote an article saying that, given the secrecy of the testing, not all of the women candidates knew each other throughout their years of preparation. It was not until 1994 that ten of the Mercury 13 were introduced to each other for the first time.[3]

Tests

Because doctors did not know all the conditions which astronauts might encounter in space, they had to guess at what tests might be required. These ranged from typical X-rays and general body physicals to the atypical; for instance, the women had to swallow a rubber tube in order to test the level of their stomach acids. Doctors tested the reflexes in the ulnar nerve of the woman's forearms by using electric shock. To induce vertigo, ice water was shot into their ears, freezing the inner ear so doctors could time how quickly they recovered. The women were pushed to exhaustion while riding specially weighted stationary bicycles, in order to test their respiration. They subjected themselves to many more invasive and uncomfortable tests.[4]

The 13

In the end, thirteen women passed the same Phase I physical examinations that the Lovelace Foundation had developed as part of NASA's astronaut selection process. Those thirteen women were:

- Myrtle Cagle

- Jerrie Cobb

- Janet Dietrich[5]

- Marion Dietrich, twin of Janet Dietrich[5]

- Wally Funk

- Sarah Gorelick (later Ratley)

- Jane "Janey" Briggs Hart

- Jean Hixson

- Rhea Woltman

- Gene Nora Stumbough (later Jessen)

- Irene Leverton

- Jerri Sloan (later Truhill)

- Bernice Steadman

At 41, Jane Hart was the oldest candidate, and was the mother of eight. Wally Funk, was the youngest, at 23.[1] Marion and Janet Dietrich were twin sisters.[5]

Additional tests

A few women took additional tests. Jerrie Cobb, Rhea Hurrle, and Wally Funk went to Oklahoma City, Oklahoma for Phase II testing, consisting of an isolation tank test and psychological evaluations.[6] Because of other family and job commitments, not all of the women were able to take these tests. Once Cobb had passed the Phase III tests (advanced aeromedical examinations using military equipment and jet aircraft), the group prepared to gather in Pensacola, Florida at the Naval School of Aviation Medicine to follow suit. Two of the women quit their jobs in order to be able to attend. A few days before they were to report, however, the women received telegrams abruptly canceling the Pensacola testing. Without an official NASA request to run the tests, the United States Navy would not allow the use of its facilities for such an unofficial project.

Funk reportedly also completed the third phase of testing, but this claim is misleading. Following NASA's cancellation of the tests, she found ways to continue being tested. She did complete most of the Phase III tests, but only by individual actions, not as part of a specific program. Cobb passed all the training exercises, ranking in the top 2% of all astronaut candidates of both genders.[7]

Regardless of the women's achievements in testing, NASA continued to exclude women as astronaut candidates for years.

- Nineteen women took astronaut fitness examinations given by the Lovelace Clinic.[6]

- Unlike NASA's male candidates, who competed in group – the women did their tests alone or in pairs.[6]

- The women passed these tests secretly while the nation was focused on John Glenn, Alan Shepard, and the other Project Mercury astronauts.[8]

House Committee Hearing on Gender Discrimination

When the Pensacola testing was cancelled, Jerrie Cobb immediately flew to Washington, D.C. to try to have the testing program resumed. She and Janey Hart wrote to President John F. Kennedy and visited Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson. Finally, on 17 and 18 July 1962, Representative Victor Anfuso (D-NY) convened public hearings before a special Subcommittee of the House Committee on Science and Astronautics.[9] Significantly, the hearings investigated the possibility of gender discrimination two years before passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 that made such actions illegal.

Cobb and Hart testified about the benefits of Lovelace's private project. Jacqueline Cochran largely undermined their testimony, talking about her concerns that setting up a special program to train a woman astronaut could hurt the space program. Jacqueline Cochran had a large say in what the Mercury 13 were doing, and how much they were allowed to be involved in because she and her husband largely funded it and because she was close with the board of trustees. When Cochran was brought into the program in 1960, she wrote many suggestions for how the program should be altered. One aspect that she wanted changed was the age requirement, which would have allowed her to be an active member of the Mercury 13. She continued to bring evidence forward that women would not be suitable for space training. For example, she proposed a project with a large group of women, and expected a significant amount to drop out due to reasons like "marriage, childbirth, and other causes". Her final statement came when she was asked outright if women should be in the space program. Cochran states "I certainly think the research should be done. Then, I can tell you afterward". Her testimony had a huge effect on the participation of the Mercury 13 in the space program.

NASA representatives George Low and Astronauts John Glenn and Scott Carpenter testified that under NASA's selection criteria women could not qualify as astronaut candidates. Glenn also believed that "The fact that women are not in this field is a fact of our social order.".[10] They correctly stated that NASA required all astronauts to be graduates of military jet test piloting programs and have engineering degrees, although John Glenn conceded that he had been assigned to NASA's Mercury Project without having earned the required college degree.[11] In 1962, women were still barred from Air Force training schools, so no American women could become test pilots of military jets. Despite the fact that several of the Mercury 13 had been employed as civilian test pilots, and many had considerably more propeller aircraft flying time than the male astronaut candidates (although not in high-performance jets, like the men), NASA refused to consider granting an equivalency for their hours in propeller airplanes.[12] Jan Dietrich had accumulated 8,000 hours, Mary Wallace Funk 3,000 hours, Irene Leverton 9,000+, and Jerrie Cobb 10,000+.[13] Although some members of the Subcommittee were sympathetic to the women's arguments because of this disparity in accepted experience, no action resulted.

Executive Assistant to Vice President Lyndon Johnson, Liz Carpenter, drafted a letter to NASA administrator James E. Webb questioning these requirements, but Johnson did not send the letter, instead writing across it, "Let's stop this now!"[14]

The pilot paradox

The qualifications for prospective astronauts had been a point of contention after the creation of NASA in 1958. The proposition for astronauts to have a background as a pilot was a logical choice, specifically test pilots with a disposition to train and learn to fly new craft designs. The consensus sought jet test pilots from the military, a field where women were not allowed at the time, and by default excluded from consideration. However, NASA also required potential astronauts to hold college degrees- a qualification that John Glenn of the Mercury 7 group did not possess. The requirement was waived for Glenn, hence allowing an environment that could have considered evaluating women for the same role. The larger issue behind this pretense, recognized by Glenn and the overall fight of the Mercury 13, was the organization of social order. Change was needed for women to be considered, but vehemently resisted in secrecy by those already benefiting from their gender-supported positions. Little to no support ever surfaced for the merit, strength, or intellect women possessed for the role of an astronaut, despite the evidence for the contrary.[15] Some obvious concerns for NASA during the space race included, but were not limited to, oxygen consumption and weight for the drag effect on takeoff. After the undeniable success of their testing, the FLATs were no longer having to prove their physical and psychological fitness. They were pushing the 'social order' to convince NASA that women had a right to hold the same roles men were granted as astronauts.[16] It was not until 1972 that an amendment to Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 finally granted women legal assistance for entering the realm of space. By 1978, the jet fighter pilot requirement was no longer an obstacle for women candidates. NASA had its first class with women that year, but they were admitted into a new category of astronaut, the mission specialist.[17] See: Sally Ride

Social considerations of the hearing

Those opposing the inclusion of women in training as astronauts created an environment where women could be seen to possess either the "virtue of patience" or the "vice of impatience"[17] in terms of U.S. success in the space race.

The space agenda of President Kennedy to put a man on the Moon had specific deadlines and scheduled events, promising to accomplish something before the Soviet Union. Sexism in the United States during the 1960s had a large impact on the way that women were allowed to participate in the space program. The men who ended up going to the Moon were portrayed as heroes by the media, and acted as such when they returned home. However, the women that were the most visible in the space program faced criticism of their work and role in the space race. There were many other women who had little to zero visibility in the public eye that did significant work in the space program. Some of those women are highlighted in the semi-fictional movie Hidden Figures.

The names that became popular in American culture for going to the Moon were not an exception to the cultural values of the time. The 1960s is included in the second wave of feminism, largely associated with women fighting for their right to be in the work place.

John Glenn was a role model for girls and boys, alike during this time. There was an increased sense of optimism during this period of time. However, there was still a gap in the way that men and women thought about their heroes. For example, Glenn was written many fan-mail letters by American civilians. Often these letters include comments on his traditionally hetero-normative "masculine" traits, such as bravery and strength. Glenn shied away from the direct support of women in the space program. His testimony in the House Hearing on Gender Discrimination shows that he did not think equally of his female counterparts.

There isn't much evidence of explicit sexism, however NASA was able to imply that they would not be allowing women into the program at that time. Often, NASA's stated reasons for employing people in the space program were certain qualifications, including the ability to employ traditional masculine gender roles. Despite the Soviet advancement to put the first woman in space in 1963 after Yuri Gagarin's orbit in 1961, the men who testified at the hearing were unmotivated. Any threat to the "patriotic chronology" of the American schedule would be considered an "impediment" or "interruption."[17] Women were forced to choose between remaining patient and missing out on substantial opportunities, or be blamed for losing the race.

Media attention

Lovelace's privately funded women's testing project received renewed media attention when Soviet cosmonaut Valentina Tereshkova became the first woman in space on June 16, 1963. In response, Clare Boothe Luce published an article in Life criticizing NASA and American decision makers.[18] By including photographs of all thirteen Lovelace finalists, she made the names of all thirteen women public for the first time. (Significant media coverage had already spotlighted some of the participants, however.) On June 17, 1963 New York Times published Jerrie Cobb's comments following the Soviet launch, saying it was "a shame that since we are eventually going to put a woman into space, we didn't go ahead and do it first."[19]

There have been countless newspaper articles, films, and books made about the Mercury 13, but they were never featured on the front page or front runner of any media network.[3]

The media often portrayed the women as unqualified candidates due to their frail and emotional structure that implies that they cannot undergo the severity that men do. On the day of July 17, 1962, a hearing was set in place for Jerrie Cobb's and Jane Hart's testimony. In further detail, Almost Astronauts: 13 Women Who Dared to Dream, justifies the hearings and statements done by the two as well as the reporters and the press. Their testimonies make inquiries about the discrimination among women and that their talents should not be prejudged or prequalified due to the fact that they are not men.[15] The book included a photo of Jerrie Cobb and Jane Hart at the witness stand that has made a huge impact on future women astronauts. A scientific writer of The Dallas Times Herald went so far as to plead with Mr. Vice President Johnson to allow women to "wear pants and shoot pool, but please do not let them into space."[16]

First American woman astronaut

Although both Cobb and Cochran made separate appeals for years afterward to restart a women's astronaut testing project, the U.S. civil space agency did not select any female astronaut candidates until Astronaut Group 8 in 1978, which selected astronauts for the operational Space Shuttle program. Astronaut Sally Ride became the first American woman in space in 1983 on STS-7, and Eileen Collins was the first woman to pilot the Space Shuttle during STS-63 in 1995. Collins also became the first woman to command a Space Shuttle mission during STS-93 in 1999. In 2005, she commanded NASA's return to flight mission, STS-114. At Collins' invitation, seven of the surviving Lovelace finalists attended her first launch,[20] ten of the FLATs attended her first command mission, and she has flown mementos for almost all of them. BBC News reported that if it wasn't for the rules that further restrained them from flying, then the first woman to go to space could have been an American.[21]

Collins on becoming an astronaut: "When I was very young and first started reading about astronauts, there were no female astronauts." She was inspired while she was a child by the Mercury astronauts and by the time she was in high school and college, more opportunities were opening up for women who wanted a part in aviation. Collins then tried out the Air Force and during her very first month's training exercises her base was visited by the newest astronaut class. This class was the first to include women. From that point she knew that "I wanted to be part of our nation's space program. It's the greatest adventure on this planet - or off the planet, for that matter. I wanted to fly the Space Shuttle."[22]

Other notable influences

The first woman in space, Russian cosmonaut Valentina Tereshkova, was arguably less qualified than the FLATs having no qualifications as a pilot or scientist. Upon meeting Jerrie Cobb, Tereshkova told her that she was her role model and asked "we always figured you would be first. What happened?" [15]

Honors and awards

- In May 2007, the eight surviving members of the group were awarded honorary doctorates by the University of Wisconsin–Oshkosh.[23]

- The Mercury 13 were awarded the Adler Planetarium Women in Space Science Award in 2005.[24]

- Jerrie Cobb was acknowledged in Clare Boothe Luce published article,[18] Life, highlighting her various flying awards and achieving four major world records.

In popular culture

- The #1 issue of the Marvel comic Captain Marvel (2012) features a fictionalized Mercury 13 participant named Helen Cobb as one of Carol Danvers's heroes.[26]

- An episode of the ABC series The Astronaut Wives Club features a fictional account of the FLATs.[27]

- A 2007 documentary She Should Have Gone to the Moon by Ulrike Kubbatta.

- A 2018 documentary Mercury 13 by David Sington for Netflix.[28][29][30]

- In the 2019 Apple TV+ miniseries For All Mankind, two of the Mercury 13 are chosen as female astronaut candidates after Soviets land the first woman on the Moon.[31]

Literature about or referencing the group

- Amelia Earhart's Daughters: the Wild and Glorious Story of American Women Aviators from World War II to the Dawn of the Space Age, by Leslie Haynsworth and David Toomey

- Right Stuff, Wrong Sex: America's First Women in Space Program by Margaret A. Weitekamp

- The Mercury 13: The True Story of Thirteen Women and the Dream of Space Flight by Martha Ackmann

- Almost Astronauts: 13 Women Who Dared to Dream by Tanya Lee Stone

- Promised the Moon: The Untold Story of the First Women in the Space Race by Stephanie Nolan

- Wally Funk's Race for Space: The Extraordinary Story of a Female Aviation Pioneer by Sue Nelson

- Women in Space: 23 Stories of First Flights, Scientific Missions, and Gravity-Breaking Adventures (Women of Action) by Karen Bush Gibson

- Fighting for Space: Two Pilots and Their Historic Battle for Female Spaceflight by Amy Shira Teitel

Past and current parallels

"Before Their Time"

Reflecting on the events of 1962 and the outcome of the Mercury 13, it was stated by astronaut Scott Carpenter that "NASA never had any intention of putting those women in space. The whole idea was foisted upon it, and it was happy to have the research data, but those women were before their time." [15] The phrase leads to a significantly subjective but important question on if there is ever a right or wrong time for any group of people with a particular mission for success in matters social or otherwise. There also remains a question on how influential social order norms are still dictating the success of the completely capable, qualified, and dedicated groups of people that face discrimination or negligence for any reason.

Reflecting on the exclusion of women from training as jet fighter pilots, The United States Air Force explicitly would not test women for high-altitude flight for lack of pressure suits in the correct sizes. Their response to the initial testing of female astronauts was that women could not become astronauts "because they had nothing to wear." [16]

In March 2019, NASA announced that there would be the first all-female space walk on the 29th of that month performed at the International Space Station. Anne McClain and Christina Koch were supposed to make history that day, but complications arose when there was a lack of spacesuit availability. NASA has had issues when it comes to spacesuit sizes claiming that they only come in medium, large and extra-large sizes. In the 1990s, NASA stopped making spacesuit sizes in small due to technical glitches.[32] This had a huge impact on women astronauts and later led to the cancellation of the all-female spacewalk on March 29, 2019. The long delayed first all-female spacewalk finally occurred on October 18, 2019, with Koch and Jessica Meir performing the task.[33]

See also

- Valentina Tereshkova, first woman in space

- Svetlana Savitskaya, second woman in space and the first to do a spacewalk

- Sally Ride, first American woman in space

- Women in NASA

Notes

- Weitekamp, Margaret A. (January 28, 2010). "Lovelace's woman in space program". NASA History Program Office. Retrieved April 20, 2018.

- "Space Medicine Association". Retrieved 2019-04-25.

- Funk, Wally. "Our History Women in Aviation History 'Mercury 13' Story by Wally..." The Ninety-Nines, Inc. Retrieved 2019-04-17.

- Anfuso, Victor L. "Hearings before the Special Subcommittee on the Selection of Astronauts". U.S. House of Representatives. Retrieved Aug 22, 2017.

- Lopez, Cory (2008-06-17). "Bay Area pilot Janet Christine Dietrich dies". San Francisco Chronicle. Hearst Communications. Retrieved April 20, 2018.

- NASA flats

- "Jerrie Cobb Poses beside Mercury Capsule". Archived from the original on December 24, 2011. Retrieved August 15, 2017.

- Qualifications for Astronauts: Hearings before the Special Subcommittee on the Selection of Astronauts Archived 2015-12-11 at the Wayback Machine, U.S. House of Representatives, 87th Cong. (1962)

- Nolan, Stephanie (October 12, 2002). "One giant leap – backward: Part 2". The Globe and Mail. Archived from the original on September 13, 2004. Retrieved December 8, 2016.

- Martha Ackman. The Mercury Thirteen: The true story of thirteen women and the dream of space flight. Random House, New York, 2003, p. 166.

- Stephanie Nolen. Promised the Moon: The untold story of the first women in the space race. Penguin Canada, Toronto, 2002, p. 240.

- Lathers, Marie (2009). "No Official Requirement: Women, History, Time, and the U.S. Space Program". Feminist Studies. 35 (1): 14–40 – via ebscohost.

- Dwayne Day (July 15, 2013). "You've come a long way, baby!". The Space Review.

- Stone, Tanya Lee (2009). Almost astronauts : 13 women who dared to dream. Weitekamp, Margaret A., 1971– (1st ed.). Somerville, Mass.: Candlewick Press. ISBN 9780763636111. OCLC 225846987.

- Kassem, Fatima Sbaity (2013). "Can Women Break Through the Political Glass Ceiling?". Party Politics, Religion, and Women's Leadership. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 203–230. doi:10.1057/9781137333216_9. ISBN 9781137333216.

- Lathers, Marie (2010). Space Oddities. doi:10.5040/9781628928976. ISBN 9781628928976.

- Luce, Clare Boothe. (June 28, 1963). "The U.S. Team Is Still Warming Up The Bench but some people simply never get the message". Life Magazine, pages: 32–33.

- "U.S. NOT PLANNING ORBIT BY WOMAN: SOME LEADING FLIERS HAVE PROTESTED EXCLUSION SEVERAL IN KEY POSTS SOVIET FLIGHT 'PREDICTABLE'." New York Times, Jun 17, 1963, pp. 8.-- via ProQuest

- Funk, Wally. "The Mercury 13 Story". The Ninety-Nines. Archived from the original on 2009-05-07. Retrieved 2009-06-12.

- Nelson, Sue (2016-07-19). "The Mercury 13: Women with the 'right stuff'". Retrieved 2019-04-17.

- "Eileen Collins - NASA's First Female Shuttle Commander". NASA. Retrieved August 14, 2020.

- "Honoring the Mercury 13 Women". University of Wisconsin – Oshkosh. May 12, 2007.

- Lucinda Hahn (June 20, 2005). "Adler board honors women who reached for the stars". Chicago Tribune.

- "Geraldyn "Jerrie" M. Cobb Papers 1952–1998". National Air and Space Museum. 2017-08-23. Retrieved 2019-04-16.

- Captain Marvel (2012) #1 (July 18, 2012)

- "The Astronaut Wives Club salutes the female astronauts that America wouldn't". 20 August 2015.

- Eric Kelsey (April 19, 2018). "'Mercury 13' chronicles women in 1960s who trained for space flight". Reuters.

- "Mercury 13 documentary on Netflix". Netflix.

- https://m.imdb.com/title/tt8139850/?ref_=m_nv_sr_1

- For All Mankind, retrieved 2019-11-08

- Schwartz, Matthew S. "NASA Scraps First All-Female Spacewalk For Want Of A Medium-Size Spacesuit". NPR. Retrieved 2019-04-17.

- Zraick, Karen (October 18, 2019). "NASA Astronauts Complete the First All-Female Spacewalk: Jessica Meir and Christina Koch ventured outside the International Space Station on Friday to replace a power controller". New York Times.

References

- Weitekamp, Margaret (2004). Right Stuff, Wrong Sex: America's First Women in Space Program. Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-7994-9.

- Marconi, Elaine M. (March 22, 2005). "Women Who Reach for the Stars". Retrieved March 23, 2006.

- Weitekamp, Margaret A. (August 17, 2005). "Lovelace's Woman in Space Program". NASA History Division. Retrieved March 23, 2006.

- Funk, Wally. "THE MERCURY 13 STORY". The Ninety-Nines. Archived from the original on April 8, 2006. Retrieved March 23, 2006.

- Oberg, James. "The Mercury 13: setting the story straight". The Space Review. Retrieved May 14, 2007.

- Ackmann, Martha (2003). The Mercury 13: the untold story of thirteen American women and the dream of space flight. New York: Random House.

- Anfuso, Victor L. "Hearings before the Special Subcommittee on the Selection of Astronauts". U.S. House of Representatives. Retrieved Aug 22, 2017.

External links

- Mercury 13 web site

- NPR feature on the FLATs

- Alexis Madrigal, "The Women Who Would Have Been Sally Ride", The Atlantic, July 24, 2012. (Tagline: "The truth is: the sexism of the day overwhelmed the science of the day.")

- Mercury 13: the untold story of women testing for spaceflight in the 1960s, Adam Gabbatt, The Guardian, April 18, 2018

- Ryan, Kathy L.; Loeppky, Jack A.; Kilgore, Donald E. (2009). "A forgotten moment in physiology: the Lovelace Woman in Space Program (1960–1962)". Advances in Physiology Education. 33 (3): 157–164. doi:10.1152/advan.00034.2009.