Metaldehyde

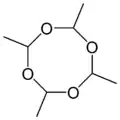

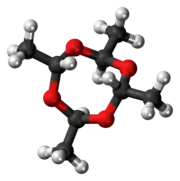

Metaldehyde is an organic compound with the formula (CH3CHO)4. It is commonly used as a pesticide against slugs, snails, and other gastropods. It is the cyclic tetramer of acetaldehyde.[1]

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

2,4,6,8-tetramethyl- | |

| Other names

metaldehyde metacetaldehyde | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.003.274 |

| KEGG | |

PubChem CID |

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C8H16O4 | |

| Molar mass | 176.212 g/mol |

| Density | 1.27 g/cm3 |

| Melting point | 246 °C (475 °F; 519 K) |

| Boiling point | sublimes at 110 to 120 °C (230 to 248 °F; 383 to 393 K) |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

Production and properties

Metaldehyde is obtained in moderate yields by treatment of acetaldehyde with various acid catalysts, such as hydrogen bromide. The reaction is reversible; upon heating to about 80 °C, metaldehyde reverts to acetaldehyde. Metaldehyde exists as a mixture of stereoisomers, molecules that differ with respect to the relative orientation of the methyl groups on the 8-membered ring.

Uses

As a pesticide

It is sold under various trade names as a molluscicide, including Antimilice, Ariotox, Blitzem (in Australia), Cekumeta, Deadline, Defender (in Australia), Halizan, Limatox, Limeol, Meta, Metason, Mifaslug, Namekil, Slug Fest Colloidel 25, and Slugit. Typically it is applied in the form of slug pellets, which normally include a wheat bait. Metaldehyde acts on the pest by contact or ingestion, and the aqueous environment inside the pest's cells readily hydrolyzes metaldehyde into acetaldehyde, the molecule associated with an alcohol hangover.

Due to the contamination of drinking water by metaldehyde's use in agriculture, a specialist organisation was established in 2008 called "The Metaldehyde Stewardship Group (MSG)".

On 19 December 2018, the British government banned the use of metaldehyde slug pellets outdoors from spring 2020; after this date it would only be legal to use it in permanent greenhouses.[2] In July 2019, the ban was overturned after the High Court in London agreed with a challenge to its legality. Metaldehyde pellets returned to the UK market for the foreseeable future.[3]

On 18 September 2020, the British government banned the use of metaldehyde slug pellets outdoors from 31 March 2022.[4]

Other uses

Metaldehyde was originally developed as a solid fuel.[5] It is still used as a camping fuel, also for military purposes, or solid fuel in lamps. It may be purchased in a tablet form to be used in small stoves, and for preheating of Primus type stoves. It is sold under the trade name of "META" by Lonza Group of Switzerland; it can be included in the field ration of some nations.

Safety and toxicity to pets

Metaldehyde has a toxicity profile identical to that for acetaldehyde, being mildly toxic[6] and a respiratory irritant at the 50 ppm level. In terms of water safety, during periods of rainfall metaldehyde pellets become agitated and can seep into natural water courses. The European Commission restricts metaldehyde levels to 0.1 µg/L in drinking water.[7]

Metaldehyde-containing slug baits should be used with caution because they are toxic to dogs and cats.[8] If ingested by dogs or cats, tremors, drooling, and restlessness will proceed to seizures and death within hours to days if treatment is not started quickly. Due to this toxicity, pet owners may want to investigate alternatives which are not as toxic to pets, such as Ferric Sodium EDTA or Iron(III) phosphate.[9] The metaldehyde tablets resemble candies and do not taste bad, making accidental ingestion possible by children or even by adults unaware of their true nature. Their use was popular during the interwar period and several cases of poisoning resulted.[10] Baits may contain a bittering agent to prevent accidental consumption by pets or children.

See also

References

- Marc Eckert, Gerald Fleischmann, Reinhard Jira, Hermann M. Bolt, Klaus Golka "Acetaldehyde" in Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, 2006, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim. doi:10.1002/14356007.a01_031.pub2.

- unnamed author (19 December 2018), Restrictions on the use of metaldehyde to protect wildlife, UK Government

- "Metaldehyde slug pellet ban overturned after legal challenge". Farmers Weekly. 2019-07-30. Retrieved 2019-08-04.

- unnamed author (18 September 2020), Outdoor use of metaldehyde to be banned to protect wildlife, UK Government

- Eschenmooser, Walter (June 1997). "100 Years of Progress with LONZA". Chimia. 51 (6): 259-269. Retrieved 8 October 2020.

- Toxicology of metaldehyde

- Maher S; et al. (2016). "Direct Analysis and Quantification of Metaldehyde in Water using Reactive Paper Spray Mass Spectrometry". Scientific Reports. 6: 35643. Bibcode:2016NatSR...635643M. doi:10.1038/srep35643. PMC 5073298. PMID 27767044.

- "Pests in Gardens and Landscapes". University of California, Davis. Retrieved 2010-08-03.

- "Slugging Out Spring". Dr. Heidi Houchen, DVM. Archived from the original on 2012-07-18.

- Miller, Reginald (December 1928). "Poisoning by "Meta Fuel" Tablets (Metacetaldehyde)". Archives of Disease in Childhood. 3 (18): 292–295. doi:10.1136/adc.3.18.292. PMC 1975025. PMID 21031743.

External links

- National Pesticide Information Center (NPIC) Information about pesticide-related topics.

- Get Rid of Slugs and Snails, Not Puppy Tails! Case Profile - National Pesticide Information Center

- Slugs and Snails - National Pesticide Information Center

- WHO/FAO Data sheet at inchem.org

- Slug controls (on Wikibooks)

- Metaldehyde in the Pesticide Properties DataBase (PPDB)