Mexica

The Mexica (Nahuatl: Mēxihcah, Nahuatl pronunciation: [meːˈʃiʔkaʔ] (![]() listen);[1] singular Mēxihcatl [meːˈʃiʔkat͡ɬ][1]), or Mexicas, were a Nahuatl-speaking indigenous people of the Valley of Mexico who were the rulers of the Aztec Empire. They were the last Nahua-speaking immigrants to enter the Basin of Mexico after the Toltec decline.[2] This group was also known as the Culhua-Mexica in recognition of its kinship alliance with the neighboring Culhua, descendants of the revered Toltecs, who occupied the Toltec capital of Tula from the tenth through twelfth centuries. The Mexica of Tenochtitlan were additionally referred to as the "Tenochca", a term associated with the name of their altepetl (city-state), Tenochtitlan, and Tenochtitlan's founding leader, Tenoch.[3] The Mexica established Mexico Tenochtitlan, a settlement on an island in Lake Texcoco. A dissident group in Mexico-Tenochtitlan separated and founded the settlement of Mexico-Tlatelolco with its own dynastic lineage. The Mexica of Tlatelolco were additionally known as Tlatelolca.

listen);[1] singular Mēxihcatl [meːˈʃiʔkat͡ɬ][1]), or Mexicas, were a Nahuatl-speaking indigenous people of the Valley of Mexico who were the rulers of the Aztec Empire. They were the last Nahua-speaking immigrants to enter the Basin of Mexico after the Toltec decline.[2] This group was also known as the Culhua-Mexica in recognition of its kinship alliance with the neighboring Culhua, descendants of the revered Toltecs, who occupied the Toltec capital of Tula from the tenth through twelfth centuries. The Mexica of Tenochtitlan were additionally referred to as the "Tenochca", a term associated with the name of their altepetl (city-state), Tenochtitlan, and Tenochtitlan's founding leader, Tenoch.[3] The Mexica established Mexico Tenochtitlan, a settlement on an island in Lake Texcoco. A dissident group in Mexico-Tenochtitlan separated and founded the settlement of Mexico-Tlatelolco with its own dynastic lineage. The Mexica of Tlatelolco were additionally known as Tlatelolca.

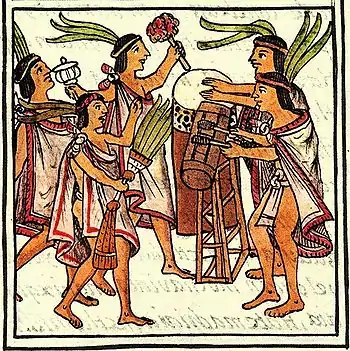

Music and dance during a One Flower ceremony, from the Florentine Codex. | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| Languages | |

| Classical Nahuatl | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Other Nahua peoples |

The name Aztec was coined by Alexander von Humboldt who combined "Aztlan" ("place of the heron"), their mythic homeland, and "tec(atl)", 'people of'.[3] In today's usage, the term "Aztec" often refers exclusively to the Mexica people of Tenochtitlan, Mēxihcah Tenochcah, a tribal designation referring only to the Mexica of Tenochtitlan, excluding Tlatelolco or Cōlhuah (Nahuatl pronunciation: [ˈkoːlwaʔ], referring to their royal genealogy tying them to Culhuacan).[4][5][nb 1][nb 2] The term Aztec is often used very broadly to refer not only to the Mexica, but also to the Nahuatl-speaking peoples or Nahuas of the Valley of Mexico and neighboring valleys.[3][6]

During the Spanish conquest, Tenochtitlan appeared in Bernal Díaz del Castillo’s tour as a grand unity of architecture, order, and brilliance. But the story of its rise from the muddy lake beds in the Basin of Mexico is one of unrelenting struggle, rivalries, conflict, suffering, and eventual triumph.[7]

History

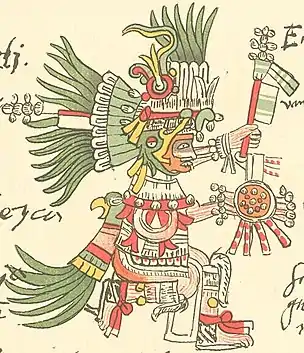

After about 1200 CE, various nomadic peoples entered the Valley of Mexico, including the Mexica. When they arrived, they "encountered the remnants of the Toltec empire (Hicks 2008; Weaver 1972)."[8] There were other groups, but all are believed to have the same origin in Aztlan.[9] Given the Mexica's religious beliefs, it is said that they were actually searching for a sign which one of their main gods, Huitzilopochtli, had given them. Over time, the Mexica separated Huitzilopochtli from Tezcatlipoca, another god that was more predominantly idolized, redefining their relative realms of power, reshaping the myths, and making him politically superior.[10]

The Mexica were to find "an eagle with a snake in its beak, perched on a prickly pear cactus."[3] Wherever they saw that was where they were meant to live. They continuously searched for the symbol. Eventually, they happened to stumble upon Lake Texcoco, where they finally saw the eagle and cactus on an island on the lake. There, "they took refuge..., naming their settlement Tenochtitlan (Among the Stone-Prickly Pear Cactus Fruit)."[3] Tenochtitlan was founded in 1325, but other researchers and anthropologists believe the year to be 1345.[3]

A dissident group of Mexica separated from the main body and settled in a location slightly to the north of Tenochtitlan. Calling their new home Tlatelolco ("Place of the Spherical Earth Mound"), the Tlatelolca were to become Tenochtitlan's persistent rivals in the Valley of Mexico.[11] The Mexica were a Nahua people, who founded their two city-states, Tenochtitlan and Tlatelolco, on raised islets in Lake Texcoco in 1325 and 1337, respectively. After the rise of the Aztec Triple Alliance, the Tenochca Mexica, the inhabitants of Tenochtitlan, assumed a dominant position over their two allied city-states, Texcoco and Tlacopan. Only a few years after Tenochtitlan was founded, the Mexica dominated the political landscape in Central Mexico until being defeated by the Spanish and their indigenous allies, mainly enemies of the Mexica, in 1519.[8]

The Mexica, once established in Tenochtitlan, built grand temples for different purposes. The Templo Mayor, nearby buildings, and associated sculptures and offerings are rich in the symbolism of Aztec cosmology that linked rain and fertility, warfare, sacrifice, and imperialism with the sacred mission to preserve the sun and the cosmic order.[12] The Templo Mayor was particularly special for many reasons, specifically since it was "the site of large-scale sacrifices of enemy warriors which served intertwined political and religious ends (Berdan 1982: 111–119; Carrasco 1991)."[12] The Templo Mayor was a double pyramid-temple dedicated to Tlaloc, the ancient Central Mexican rain god, and Huitzilopochtli, the Mexica tribal numen, who, as the politically-dominant deity in Mexico, was associated with the sun.[13]

The Mexica are eponymous of the place name Mexico Mēxihco [meːˈʃiʔko]. It refers to the interconnected settlements in the valley that became the site of what is now Mexico City, which held natural, geographical, and population advantages, as the metropolitan center of the region of the future Mexican state. In the end, "the Mexica of Tenochtitlan were conquered by the Spanish conquistadors under Fernando (Hernán) Cortés in 1521."[3]

The area was expanded upon in the wake of the Spanish conquest of Mexico and administered from the former Aztec capital as New Spain.

Like many of the peoples around them, the Mexica spoke Nahuatl which, with the expansion of the Aztec Empire, became the lingua franca in other areas.[14] The form of Nahuatl used in the 16th century, when it began to be written in the Latin alphabet introduced by the Spanish, became known as Classical Nahuatl. Nahuatl is still spoken today by over 1.5 million people, mostly in Mexico.[15]

Notes

- Smith 1997, p. 4 writes "For many the term 'Aztec' refers strictly to the inhabitants of Tenochtitlan (the Mexica people), or perhaps the inhabitants of the Valley of Mexico, the highland basin where the Mexica and certain other Aztec groups lived. I believe it makes more sense to expand the definition of "Aztec" to include the peoples of nearby highland valleys in addition to the inhabitants of the Valley of Mexico. In the final few centuries before the arrival of the Spaniards in 1519 the peoples of this wider area all spoke the Nahuatl language (the language of the Aztecs), and they all traced their origins to a mythical place called Aztlan (Aztlan is the origin of the term "Aztec," a modern label that was not used by the Aztecs themselves)"

- Lockhart 1992, p. 1 writes "These people I call the Nahuas, a name they sometimes used themselves and the one that has become current today in Mexico, in preference to Aztecs. The latter term has several decisive disadvantages: it implies a quasi-national unity that did not exist, it directs attention to an ephemeral imperial agglomeration, it is attached specifically to the pre-conquest period, and by the standards of the time, its use for anyone other than the Mexica (the inhabitants of the imperial capital, Tenochtitlan) would have been improper even if it had been the Mexica's primary designation, which it was not"

References

- Nahuatl Dictionary. (1990). Wired Humanities Project. University of Oregon. Retrieved August 29, 2012, from link

- Carrasco, Pedro. "Mexica." In Carrasco, David L. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Mesoamerican Cultures, vol 2 : Oxford University Press, (2001), 297-298.

- Frances F. Berdan "Mesoamerica: Mexica." In Encyclopedia of Mexico: History, Society & Culture, edited by Michael S. Werner. Routledge, 1998.

- Barlow 1949.

- León-Portilla 2000.

- Hanson, Victor Davis (2007-12-18). Carnage and Culture: Landmark Battles in the Rise to Western Power. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-307-42518-8.

- Carrasco, Davíd. The Aztecs: A Very Short Introduction. Very Short Introductions. US: Oxford University Press (2012), p 17.

- Cathy Willermet et al., "Biodistances Among Mexica, Maya, Toltec, and Totonac Groups of Central and Coastal Mexico / Las Distancias Biológicas Entre Los Mexicas, Mayas, Toltecas, y Totonacas de México Central y Zona Costera." Chungara: Revista De Antropología Chilena 45, no. 3 (2013), 449.

- Ellis, Elisabeth (2011). World History. United States: Pearson Education Inc. p. 192. ISBN 978-0-13-372048-8.

- Emily Umberger "Tezcatlipoca and Huitzilopochtli: Political Dimensions of Aztec Deities." In Tezcatlipoca: Trickster and Supreme Deity, edited by Baquedano Elizabeth, 83-112. University Press of Colorado, (2014) 86.

- Eloise Q. Keber "Nahua Rulers, Pre Hispanic." In Encyclopedia of Mexico: History, Society & Culture, edited by Michael S. Werner. Routledge, 1998.

- Peter N. Peregrine et al. Ember, eds. 2002. Encyclopedia of Prehistory: Volume 5: Middle America. 1 online resource (XXIX, 462 pages) vols. Boston, MA: Springer US, 33.

- Emily Umberger "Antiques, Revivals, and References to the past in Aztec Art." RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics, no. 13 (1987): 66.

- Susan T. Evans, "Postclassic Cultures of Mesoamerica." In Encyclopedia of Archaeology, edited by Deborah M. Pearsall. Elsevier Science & Technology, 2008.

- INEGI, [Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas, Geografia e Informática] (2005). Perfil sociodemográfica de la populación hablante de náhuatl (PDF). XII Censo General de Población y Vivienda 2000 (in Spanish) (Publicación única ed.). Aguascalientes, Mex.: INEGI. ISBN 978-970-13-4491-0. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 October 2008. Retrieved 2008-12-02.

Sources

- Andrews, James Richard. Introduction to classical Nahuatl. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2003. ISBN 0-8061-3452-6.

- Barlow, Robert H. (1945). "Some Remarks On The Term "Aztec Empire"". The Americas. 1 (3): 345–349. doi:10.2307/978159. JSTOR 978159.

- Barlow, Robert H. (1949). Extent Of The Empire Of Culhua Mexica. University of California Press.

- Berdan, Frances F. "Mesoamerica: Mexica." In Encyclopedia of Mexico: History, Society & Culture, edited by Michael S. Werner. Routledge, 1998.

- Evans, Susan Toby. "Postclassic Cultures of Mesoamerica." In Encyclopedia of Archaeology, edited by Deborah M. Pearsall. Elsevier Science & Technology, 2008.

- Keber, Eloise Quiñones. "Nahua Rulers, Pre Hispanic." In Encyclopedia of Mexico: History, Society & Culture, edited by Michael S. Werner. Routledge, 1998.

- León-Portilla, Miguel (1992). Fifteen Poets of the Aztec World. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-2441-4. OCLC 243733946.

- Lockhart, James (1992). The Nahuas After the Conquest: A Social and Cultural History of the Indians of Central Mexico, Sixteenth Through Eighteenth Centuries. Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-1927-8.

- León-Portilla, Miguel (2000). "Aztecas, disquisiciones sobre un gentilicio". Estudios de la Cultura Nahuatl. 31: 307–313.

- Peregrine, Peter N., and Melvin. Ember, eds. 2002. Encyclopedia of Prehistory: Volume 5: Middle America. 1 online resource (XXIX, 462 pages) vols. Boston, MA: Springer US.

- Smith, Michael E. (1997). The Aztecs (first ed.). Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-0-631-23015-1. OCLC 48579073.

- Umberger, Emily. "Tezcatlipoca and Huitzilopochtli: Political Dimensions of Aztec Deities." In Tezcatlipoca: Trickster and Supreme Deity, edited by Baquedano Elizabeth, 83–112. University Press of Colorado, 2014.

- Umberger, Emily. "Antiques, Revivals, and References to the past in Aztec Art." RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics, no. 13 (1987): 62–105.

- Willermet, Cathy, Heather J.H. Edgar, Corey Ragsdale, and B. Scott Aubry. "Biodistances Among Mexica, Maya, Toltec, and Totonac Groups of Central and Coastal Mexico / Las Distancias Biológicas Entre Los Mexicas, Mayas, Toltecas, y Totonacas de México Central y Zona Costera." Chungara: Revista De Antropología Chilena 45, no. 3 (2013): 447–59.