Lingua franca

A lingua franca (/ˌlɪŋɡwə ˈfræŋkə/ (![]() listen); lit. 'Frankish tongue'; for plurals see § Usage notes),[1] also known as a bridge language, common language, trade language, auxiliary language, vehicular language, or link language, is a language or dialect systematically used to make communication possible between groups of people who do not share a native language or dialect, particularly when it is a third language that is distinct from both of the speakers' native languages.[2]

listen); lit. 'Frankish tongue'; for plurals see § Usage notes),[1] also known as a bridge language, common language, trade language, auxiliary language, vehicular language, or link language, is a language or dialect systematically used to make communication possible between groups of people who do not share a native language or dialect, particularly when it is a third language that is distinct from both of the speakers' native languages.[2]

Lingua francas have developed around the world throughout human history, sometimes for commercial reasons (so-called "trade languages" facilitated trade), but also for cultural, religious, diplomatic and administrative convenience, and as a means of exchanging information between scientists and other scholars of different nationalities.[3][4] The term is taken from the medieval Mediterranean Lingua Franca, a Romance-based pidgin language used (especially by traders and seamen) as a lingua franca in the Mediterranean Basin from the 11th to the 19th century. A world language – a language spoken internationally and by many people – is a language that may function as a global lingua franca.

Characteristics

A lingua franca is any language used for communication between people who do not share a native language.[5] It can refer to mixed languages such as pidgins and creoles used for communication between language groups. It can also refer to languages which are native to one nation (often a colonial power) but used as a second language for communication between diverse language communities in a colony or former colony.[6] Lingua franca is a functional term, independent of any linguistic history or language structure.[7]

Lingua francas are often pre-existing languages with native speakers, but they can also be pidgin or creole languages developed for that specific region or context. Pidgin languages are rapidly developed and simplified combinations of two or more established languages, while creoles are generally viewed as pidgins that have evolved into fully complex languages in the course of adaptation by subsequent generations.[8] Pre-existing lingua francas such as French are used to facilitate intercommunication in large-scale trade or political matters, while pidgins and creoles often arise out of colonial situations and a specific need for communication between colonists and indigenous peoples.[9] Pre-existing lingua francas are generally widespread, highly developed languages with many native speakers. Conversely, pidgin languages are very simplified means of communication, containing loose structuring, few grammatical rules, and possessing few or no native speakers. Creole languages are more developed than their ancestral pidgins, utilizing more complex structure, grammar, and vocabulary, as well as having substantial communities of native speakers.[10]

Whereas a vernacular language is the native language of a specific geographical community, a lingua franca is used beyond the boundaries of its original community, for trade, religious, political, or academic reasons. For example, English is a vernacular in the United Kingdom but is used as a lingua franca in the Philippines, alongside Filipino. Arabic, French, Mandarin Chinese, Spanish, Portuguese, Hindustani, and Russian serve a similar purpose as industrial/educational lingua francas, across regional and national boundaries.

International auxiliary languages such as Esperanto and Lingua Franca Nova have not had a great degree of adoption globally, so they cannot currently be described as global lingua francas.[11]

Etymology

The term lingua franca derives from Mediterranean Lingua Franca, the pidgin language that people around the Levant and the eastern Mediterranean Sea used as the main language of commerce and diplomacy from late medieval times, especially during the Renaissance era, to the 18th century.[12][6] At that time, Italian-speakers dominated seaborne commerce in the port cities of the Ottoman Empire and a simplified version of Italian, including many loan words from Greek, Old French, Portuguese, Occitan, and Spanish as well as Arabic and Turkish came to be widely used as the "lingua franca" (in the generic sense) of the region.

In Lingua Franca (the specific language), lingua means a language, as in Italian, and franca is related to phrankoi in Greek and faranji in Arabic as well as the equivalent Italian and Portuguese. In all three cases, the literal sense is "Frankish", leading to the direct translation: "language of the Franks". During the late Byzantine Empire, "Franks" was a term that applied to all Western Europeans.[13][14][15]

Through changes of the term in literature, Lingua Franca has come to be interpreted as a general term for pidgins, creoles, and some or all forms of vehicular languages. This transition in meaning has been attributed to the idea that pidgin languages only became widely known from the 16th century on due to European colonization of continents such as The Americas, Africa, and Asia. During this time, the need for a term to address these pidgin languages arose, hence the shift in the meaning of Lingua Franca from a single proper noun to a common noun encompassing a large class of pidgin languages.[16]

As recently as the late 20th century, some restricted the use of the generic term to mean only mixed languages that are used as vehicular languages, its original meaning.[17]

Douglas Harper's Online Etymology Dictionary states that the term Lingua Franca (as the name of the particular language) was first recorded in English during the 1670s,[18] although an even earlier example of the use of Lingua Franca in English is attested from 1632, where it is also referred to as "Bastard Spanish".[19]

Usage notes

The term is well established in its naturalization to English, which is why major dictionaries do not italicize it as a "foreign" term.[20][21][22]

Its plurals in English are lingua francas and linguae francae,[21][22] with the former being first-listed[21][22] or only-listed[20] in major dictionaries.

Examples

The use of lingua francas has existed since antiquity. Latin and Koine Greek were the lingua francas of the Roman Empire and the Hellenistic culture. Akkadian (died out during Classical antiquity) and then Aramaic remained the common languages of a large part of Western Asia from several earlier empires.[23][24]

The Hindustani language (Hindi-Urdu) is the lingua franca of Pakistan and Northern India.[25][26] Many Indian states have adopted the Three-language formula in which students in Hindi-speaking states are taught: "(a) Hindi (with Sanskrit as part of the composite course); (b) Urdu or any other modern Indian language and (c) English or any other modern European language." The order in non-Hindi speaking states is: "(a) the regional language; (b) Hindi; (c) Urdu or any other modern Indian language excluding (a) and (b); and (d) English or any other modern European language."[27] Hindi has also emerged as a lingua franca for the locals of Arunachal Pradesh, a linguistically diverse state in Northeast India.[28][29] It is estimated that 90 percent of the state's population knows Hindi.[30]

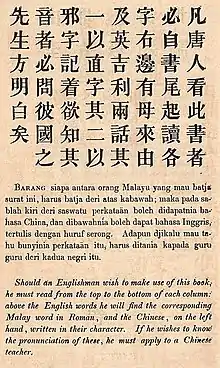

Indonesian – which originated from a Malay language variant spoken in Riau – is the official language and a lingua franca in Indonesia and widely understood across the Malay world including Malaysia, Singapore and Brunei, although Javanese has more native speakers. Still, Indonesian is the sole official language and is spoken throughout the country.

.svg.png.webp)

Swahili developed as a lingua franca between several Bantu-speaking tribal groups on the east coast of Africa with heavy influence from Arabic.[31] The earliest examples of writing in Swahili are from 1711.[32] In the early 19th century the use of Swahili as a lingua franca moved inland with the Arabic ivory and slave traders. It was eventually adopted by Europeans as well during periods of colonization in the area. German colonizers used it as the language of administration in German East Africa, later becoming Tanganyika, which influenced the choice to use it as a national language in what is now independent Tanzania.[31]

In the European Union, the use of English as a lingua franca has led researchers to investigate whether a new dialect of English (Euro English) has emerged.[33]

When the United Kingdom became a colonial power, English served as the lingua franca of the colonies of the British Empire. In the post-colonial period, some of the newly created nations which had multiple indigenous languages opted to continue using English as an official language.

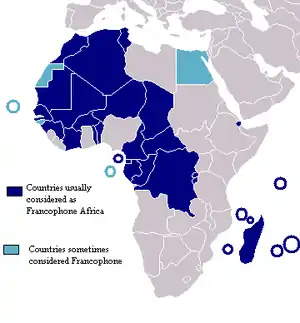

French is still a lingua franca in most Western and Central African countries and an official language of many, a remnant of French and Belgian colonialism. These African countries and others are members of the Francophonie.

Russian is in use and widely understood in Central Asia and the Caucasus, areas formerly part of the Russian Empire and Soviet Union, and in much of Central and Eastern Europe. It remains the official language of the Commonwealth of Independent States. Russian is also one of the six official languages of the United Nations.[34]

Persian, an Iranian language, is the official language of Iran, Afghanistan (Dari) and Tajikistan (Tajik). It acts as a lingua franca in both Iran and Afghanistan between the various ethnic groups in those countries. The Persian language in South Asia, before the British colonized the Indian subcontinent, was the region's lingua franca and a widely used official language in north India and Pakistan.

Old Church Slavonic, an Eastern South Slavic language, is the first Slavic literary language. Between 9th and 11th century it was lingua franca of great part of the predominantly Slavic states and populations in Southeast and Eastern Europe, in liturgy and church organization, culture, literature, education and diplomacy. [35][36]

Hausa can also be seen as a lingua franca because it is the language of communication between speakers of different languages in Northern Nigeria and other West African countries.

In Qatar, the medical community is primarily made up of workers from countries without English as a native language. In medical practices and hospitals, nurses typically communicate with other professionals in English as a lingua franca.[37] This occurrence has led to interest in researching the consequences and affordances of the medical community communicating in a lingua franca.[37]

The only documented sign language used as a lingua franca is Plains Indian Sign Language, used across much of North America. It was used as a second language across many indigenous peoples. Alongside or a derivation of Plains Indian Sign Language was Plateau Sign Language, now extinct. Inuit Sign Language could be a similar case in the Arctic among the Inuit for communication across oral language boundaries, but little research exists.

See also

- Rosetta Stone

- Global language system

- International auxiliary language

- Koiné language

- Language contact

- List of languages by number of native speakers

- List of languages by total number of speakers

- Mediterranean Lingua Franca

- Mixed language

- Mutual intelligibility

- Pidgin

- Interlinguistics

- Universal language

- Working language

- World language

References

- "lingua franca – definition of lingua franca in English from the Oxford dictionary". Oxforddictionaries.com. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- Viacheslav A. Chirikba, "The problem of the Caucasian Sprachbund" in Pieter Muysken, ed., From Linguistic Areas to Areal Linguistics, 2008, p. 31. ISBN 90-272-3100-1

- Nye, Mary Jo (2016). "Speaking in Tongues: Science's centuries-long hunt for a common language". Distillations. 2 (1): 40–43. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- Gordin, Michael D. (2015). Scientific Babel: How Science Was Done Before and After Global English. Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226000299.

- "vehicular, adj." OED Online. Oxford University Press, July 2018. Web. 1 November 2018.

- LINGUA FRANCA:CHIMERA OR REALITY? (PDF). 2010. ISBN 9789279189876.

- Intro Sociolinguistics – Pidgin and Creole Languages: Origins and Relationships – Notes for LG102, – University of Essex, Prof. Peter L. Patrick – Week 11, Autumn term.

- Romaine, Suzanne (1988). Pidgin and Creole Languages. Longman.

- "Lingua Franca, Pidgin, and Creole". 3 April 2015. Retrieved 29 April 2019.

- "The Difference Between Lingua Franca, Pidgin, and Creole Languages". Teacher Finder. Retrieved 29 April 2019.

- Directorate-General for Translation, European Commission (2011). "Studies on translation and multilingualism" (PDF). Europa (web portal). Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 November 2012.

- "lingua franca | linguistics". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 8 August 2017.

- Lexico Triantaphyllide online dictionary, Greek Language Center (Kentro Hellenikes Glossas), lemma Franc ( Φράγκος Phrankos), Lexico tes Neas Hellenikes Glossas, G.Babiniotes, Kentro Lexikologias(Legicology Center) LTD Publications. Komvos.edu.gr. 2002. ISBN 960-86190-1-7. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

Franc and (prefix) franco- (Φράγκος Phrankos and φράγκο- phranko-)

- "An etymological dictionary of modern English : Weekley, Ernest, 1865–1954 : Free Download & Streaming : Internet Archive". Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- Archived 12 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- Brosch, C. (2015). "On the Conceptual History of the Term Lingua Franca". Apples – Journal of Applied Language Studies. 9 (1): 71–85. doi:10.17011/apples/2015090104.

- Webster's New World Dictionary of the American Language, Simon and Schuster, 1980

- "Online Etymology Dictionary". Etymonline.com. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- Morgan, J. (1632). A Compleat History of the Present Seat of War in Africa, Between the Spaniards and Algerines. p. 98. Retrieved 8 June 2013.

- Oxford Dictionaries, Oxford Dictionaries Online, Oxford University Press.

- Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, archived from the original on 25 September 2015, retrieved 25 February 2018.

- Merriam-Webster, MerriamWebster's Collegiate Dictionary, Merriam-Webster.

- Ostler, 2005 pp. 38–40

- Ostler, 2010 pp. 163–167

- Mohammad Tahsin Siddiqi (1994), Hindustani-English code-mixing in modern literary texts, University of Wisconsin,

... Hindustani is the lingua franca of both India and Pakistan ...

- Lydia Mihelič Pulsipher; Alex Pulsipher; Holly M. Hapke (2005), World Regional Geography: Global Patterns, Local Lives, Macmillan, ISBN 0-7167-1904-5,

... By the time of British colonialism, Hindustani was the lingua franca of all of northern India and what is today Pakistan ...

- "Three Language Formula". Government of India Ministry of Human Resource Development Department of Education. Archived from the original on 22 February 2012. Retrieved 16 May 2016.

- Chandra, Abhimanyu (22 August 2014). "How Hindi Became the Language of Choice in Arunachal Pradesh." Scroll.in. Retrieved 12 March 2019.

- http://www.censusindia.gov.in/2011census/C-17.html

- Roychowdhury, Adrija (27 February 2018). "How Hindi Became Arunachal Pradesh's Lingua Franca." The Indian Express. Retrieved 12 March 2019.

- "Swahili language". Encyclopædia Britannica. 27 August 2014. Retrieved 29 April 2019.

- E. A. Alpers, Ivory and Slaves in East Central Africa, London, 1975.., pp. 98–99 ; T. Vernet, "Les cités-Etats swahili et la puissance omanaise (1650–1720), Journal des Africanistes, 72(2), 2002, pp. 102–105.

- Mollin, Sandra (2005). Euro-English assessing variety status. Tübingen: Narr. ISBN 382336250X.

- "Department for General Assembly and Conference Management – What are the official languages of the United Nations?". United Nations. Archived from the original on 12 October 2007. Retrieved 25 January 2008.

- Wells, John C. (2008), Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.), Longman, ISBN 9781405881180

- Jones, Daniel (2003) [1917], Peter Roach; James Hartmann; Jane Setter (eds.), English Pronouncing Dictionary, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-3-12-539683-8

- Tweedie, Gregory; Johnson, Robert. "Listening instruction and patient safety: Exploring medical English as a lingua franca (MELF) for nursing education". Retrieved 6 January 2018.

Further reading

- Hall, R.A. Jr. (1966). Pidgin and Creole Languages. Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-0173-9.

- Heine, Bernd (1970). Status and Use of African Lingua Francas. ISBN 3-8039-0033-6.

- Kahane, Henry Romanos (1958). The Lingua Franca in the Levant.

- Melatti, Julio Cezar (1983). Índios do Brasil (48 ed.). São Paulo: Hucitec Press.

- Ostler, Nicholas (2005). Empires of the Word. London: Harper. ISBN 978-0-00-711871-7.

- Ostler, Nicholas (2010). The Last Lingua Franca. New York: Walker. ISBN 978-0-8027-1771-9.

External links

- "English – the universal language on the Internet?".

- "Lingua franca del Mediterraneo o Sabir of professor Francesco Bruni (in Italian)". Archived from the original on 28 March 2009.

- "Sample texts". Archived from the original on 9 April 2009. from Juan del Encina, Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme, Carlo Goldoni's L'Impresario da Smyrna, Diego de Haedo and other sources

- "An introduction to the original Mediterranean Lingua Franca". Archived from the original on 8 April 2010.